This post is a not a so secret analogy for the AI Alignment problem. Via a fictional dialog, Eliezer explores and counters common questions to the Rocket Alignment Problem as approached by the Mathematics of Intentional Rocketry Institute.

MIRI researchers will tell you they're worried that "right now, nobody can tell you how to point your rocket’s nose such that it goes to the moon, nor indeed any prespecified celestial destination."

Popular Comments

Recent Discussion

The Löwenheim–Skolem theorem implies, among other things, that any first-order theory whose symbols are countable, and which has an infinite model, has a countably infinite model. This means that, in attempting to refer to uncountably infinite structures (such as in set theory), one "may as well" be referring to an only countably infinite structure, as far as proofs are concerned.

The main limitation I see with this theorem is that it preserves arbitrarily deep quantifier nesting. In Peano arithmetic, it is possible to form statements that correspond (under the standard interpretation) to arbitrary statements in the arithmetic hierarchy (by which I mean, the union of and for arbitrary n). Not all of these statements are computable. In general, the question of whether a given statement is...

The axioms of U are recursively enumerable. You run all M(i,j) in parallel and output a new axiom whenever one halts. That's enough to computably check a proof if the proof specifies the indices of all axioms used in the recursive enumeration.

A friend has spent the last three years hounding me about seed oils. Every time I thought I was safe, he’d wait a couple months and renew his attack:

“When are you going to write about seed oils?”

“Did you know that seed oils are why there’s so much {obesity, heart disease, diabetes, inflammation, cancer, dementia}?”

“Why did you write about {meth, the death penalty, consciousness, nukes, ethylene, abortion, AI, aliens, colonoscopies, Tunnel Man, Bourdieu, Assange} when you could have written about seed oils?”

“Isn’t it time to quit your silly navel-gazing and use your weird obsessive personality to make a dent in the world—by writing about seed oils?”

He’d often send screenshots of people reminding each other that Corn Oil is Murder and that it’s critical that we overturn our lives...

I am perhaps not speaking as precisely as I should be. I appreciate your comments.

I believe it's correct to say that if you consider all of the food/energy we consumed in the past 50+ million years, it's virtually all plants.

The past 2-2.5 million years had us introducing more animal products to greater or lesser extents. Some were able to subsist on mostly animal products. Some consumed them very rarely.

In that sense it is a relatively recent introduction. My main point is that given our evolutionary history, the idea that plants would be healthier for us...

Warning: This post might be depressing to read for everyone except trans women. Gender identity and suicide is discussed. This is all highly speculative. I know near-zero about biology, chemistry, or physiology. I do not recommend anyone take hormones to try to increase their intelligence; mood & identity are more important.

Why are trans women so intellectually successful? They seem to be overrepresented 5-100x in eg cybersecurity twitter, mathy AI alignment, non-scam crypto twitter, math PhD programs, etc.

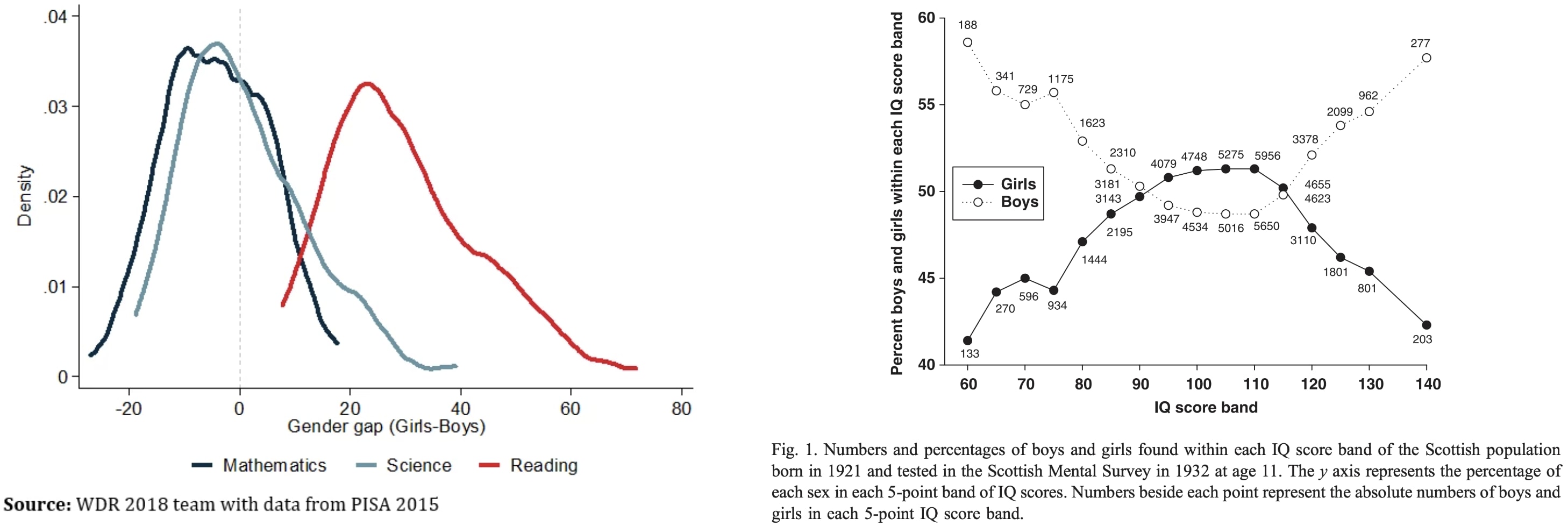

To explain this, let's first ask: Why aren't males way smarter than females on average? Males have ~13% higher cortical neuron density and 11% heavier brains (implying more area?). One might expect males to have mean IQ far above females then, but instead the means and medians are similar:

My theory...

performance gap of trans women over women

The post is about the performance gap of trans women over men, not women.

The history of science has tons of examples of the same thing being discovered multiple time independently; wikipedia has a whole list of examples here. If your goal in studying the history of science is to extract the predictable/overdetermined component of humanity's trajectory, then it makes sense to focus on such examples.

But if your goal is to achieve high counterfactual impact in your own research, then you should probably draw inspiration from the opposite: "singular" discoveries, i.e. discoveries which nobody else was anywhere close to figuring out. After all, if someone else would have figured it out shortly after anyways, then the discovery probably wasn't very counterfactually impactful.

Alas, nobody seems to have made a list of highly counterfactual scientific discoveries, to complement wikipedia's list of multiple discoveries.

To...

I guess (but don't know) that most people who downvote Garrett's comment overupdated on intuitive explanations of singular learning theory, not realizing that entire books with novel and nontrivial mathematical theory have been written on it.

Maybe by the time we cotton on properly, they're somewhere past us at the top end.

Great point. I agree that there are lots of possible futures where that happens. I'm imagining a couple of possible cases where this would matter:

- Humanity decides to stop AI capabilities development or slow it way down, so we have sub-ASI systems for a long time (which could be at various levels of intelligence, from current to ~human). I'm not too optimistic about this happening, but there's certainly been a lot of increasing AI governance momentum in the last year.

- Ali

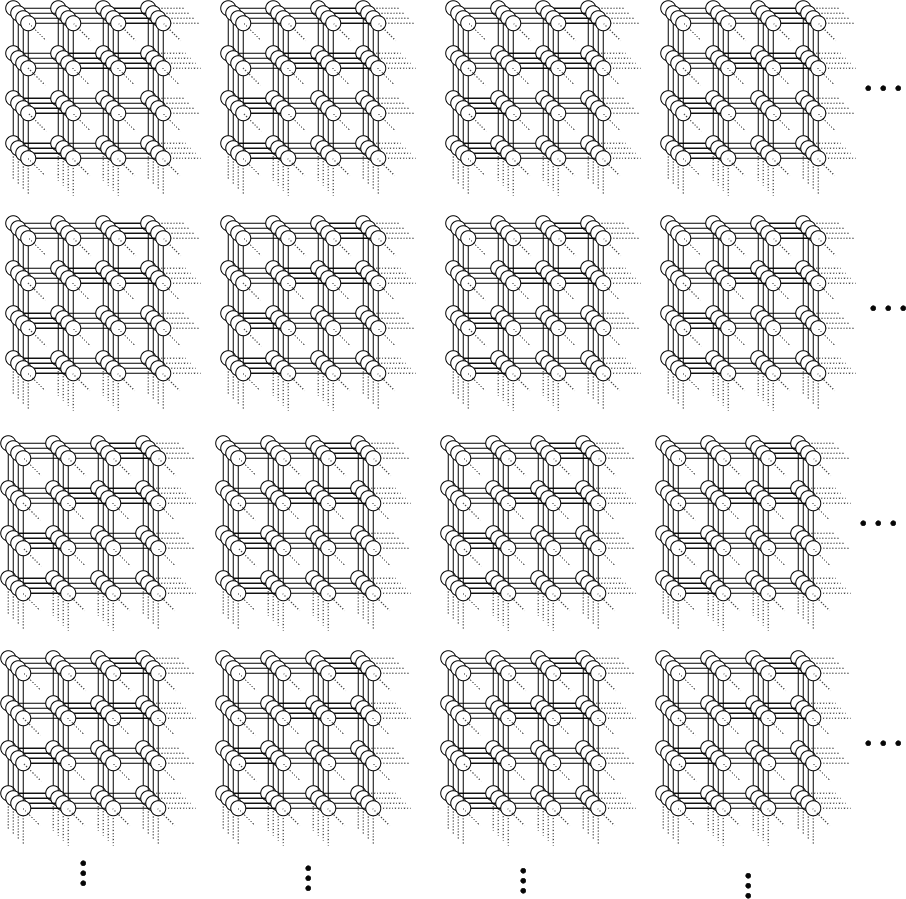

The point is that you are just given some graph. This graph is expected to have subgraphs which are lattice graphs. But you don't know where they are. And the graph is so big that you can't iterate the entire graph to find these lattices. Therefore you need a way to embed the graph without traversing it fully.

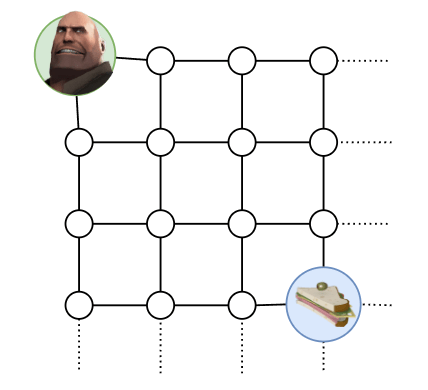

You want to get to your sandwich:

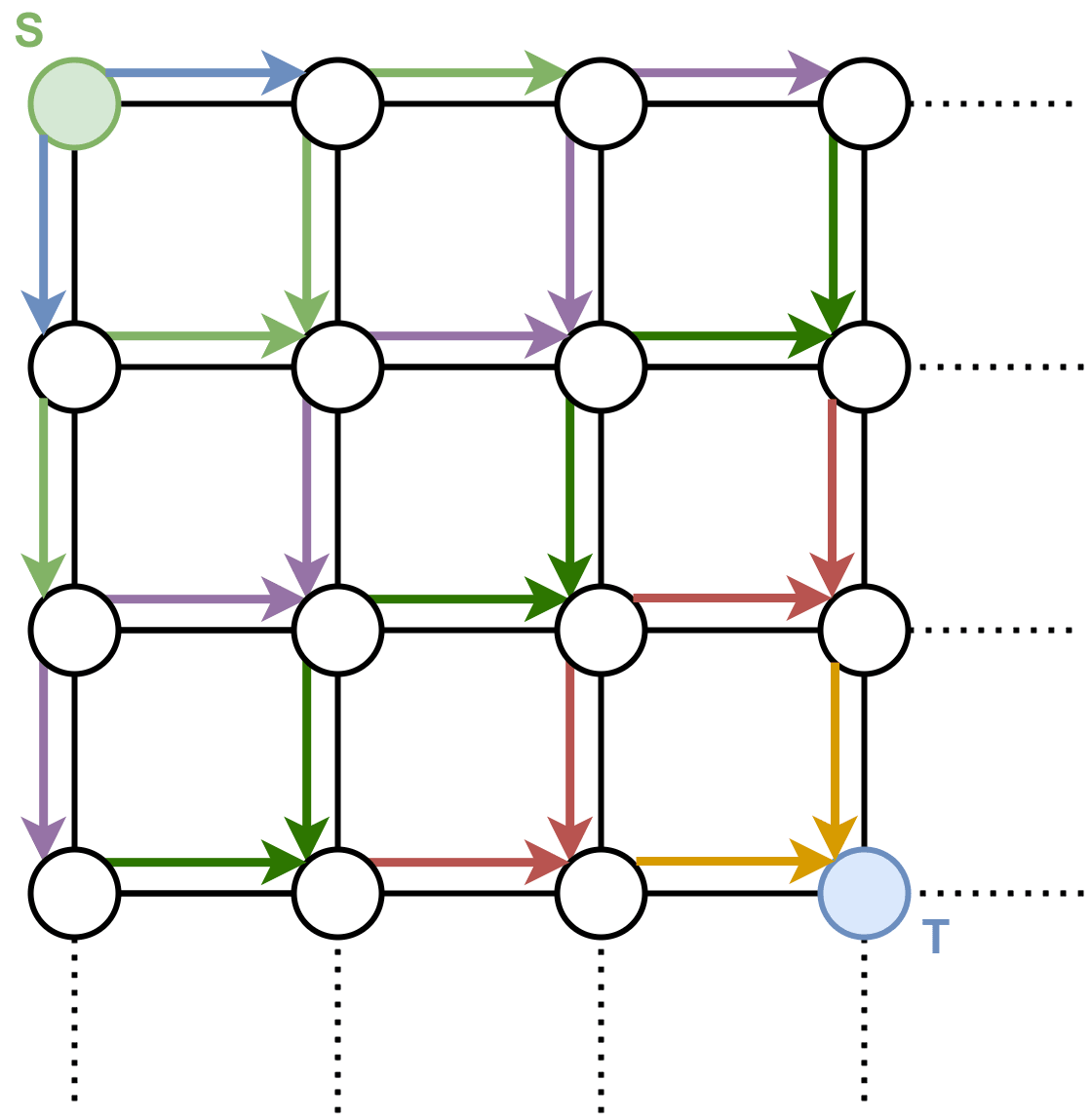

Well, that’s easy. Apparently we are in some kind of grid world, which is presented to us in the form of a lattice graph, where each vertex represents a specific world state, and the edges tell us how we can traverse the world states. We just do BFS to go from (where we are) to (where the sandwich is):

Ok that works, and it’s also fast. It’s , where is the number of vertices and is the number of edges... well at least for small graphs it’s fast. What about this graph:

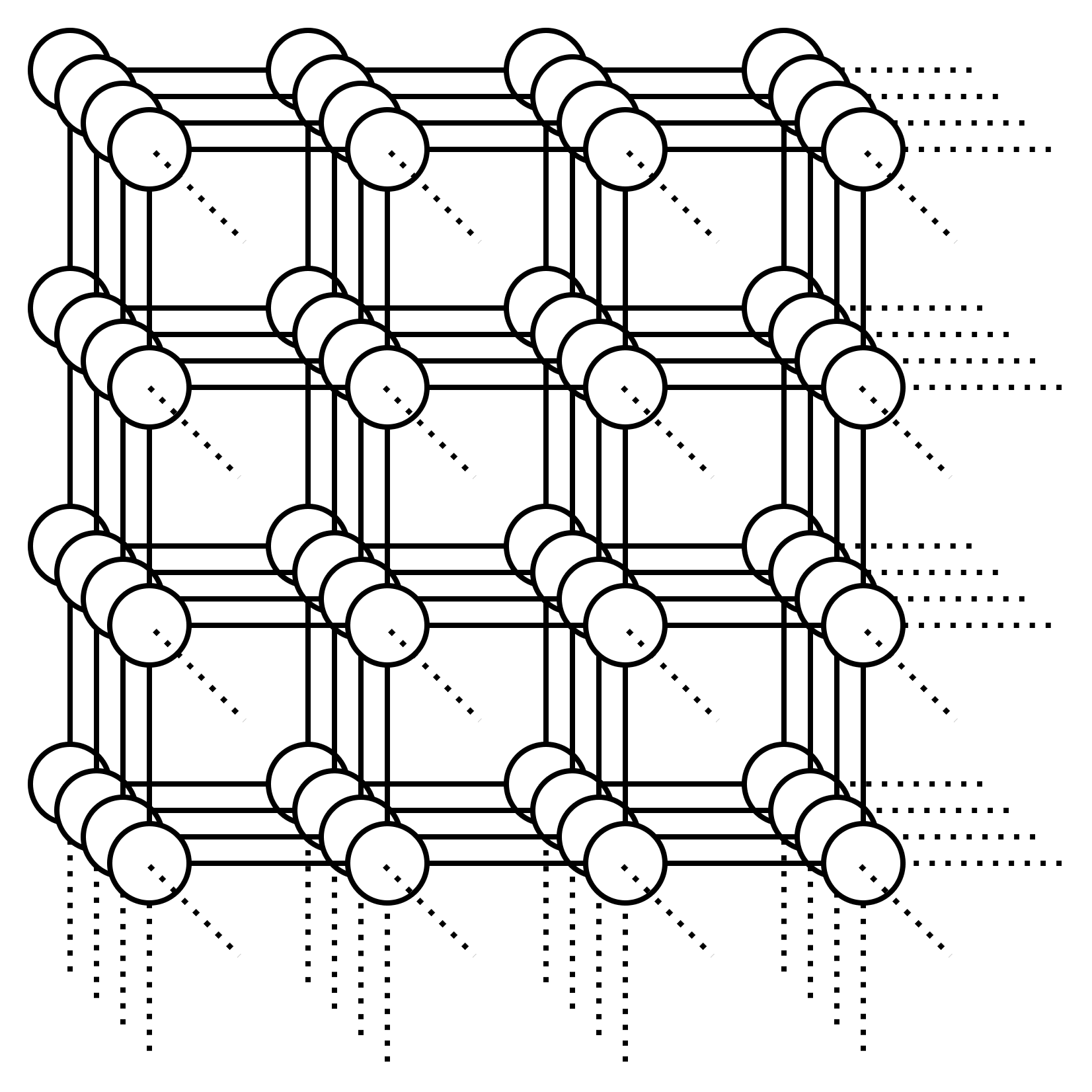

Or what about this graph:

In fact, what about a 100-dimensional lattice graph with a side length of only 10 vertices? We will have vertices in this graph.

With...

I might not understand exactly what you are saying. Are you saying that the problem is easy when you have a function that gives you the coordinates of an arbitrary node? Isn't that exactly the embedding function? So are you not therefore assuming that you have an embedding function?

I agree that once you have such a function the problem is easy, but I am confused about how you are getting that function in the first place. If you are not given it, then I don't think it is super easy to get.

In the OP I was assuming that I have that function, but I was saying ...

It seems to me worth trying to slow down AI development to steer successfully around the shoals of extinction and out to utopia.

But I was thinking lately: even if I didn’t think there was any chance of extinction risk, it might still be worth prioritizing a lot of care over moving at maximal speed. Because there are many different possible AI futures, and I think there’s a good chance that the initial direction affects the long term path, and different long term paths go to different places. The systems we build now will shape the next systems, and so forth. If the first human-level-ish AI is brain emulations, I expect a quite different sequence of events to if it is GPT-ish.

People genuinely pushing for AI speed over care (rather than just feeling impotent) apparently think there is negligible risk of bad outcomes, but also they are asking to take the first future to which there is a path. Yet possible futures are a large space, and arguably we are in a rare plateau where we could climb very different hills, and get to much better futures.

From a purely utilitarian standpoint, I'm inclined to think that the cost of delaying is dwarfed by the number of future lives saved by getting a better outcome, assuming that delaying does increase the chance of a better future.

That said, after we know there's "no chance" of extinction risk, I don't think delaying would likely yield better future outcomes. On the contrary, I suspect getting the coordination necessary to delay means it's likely that we're giving up freedoms in a way that may reduce the value of the median future and increase the chance of ...

TL;DR: This post discusses our recent empirical work on detecting measurement tampering and explains how we see this work fitting into the overall space of alignment research.

When training powerful AI systems to perform complex tasks, it may be challenging to provide training signals that are robust under optimization. One concern is measurement tampering, which is where the AI system manipulates multiple measurements to create the illusion of good results instead of achieving the desired outcome. (This is a type of reward hacking.)

Over the past few months, we’ve worked on detecting measurement tampering by building analogous datasets and evaluating simple techniques. We detail our datasets and experimental results in this paper.

Detecting measurement tampering can be thought of as a specific case of Eliciting Latent Knowledge (ELK): When AIs successfully tamper with...

looking at your code - seems like there's an option for next-token prediction in the initial finetuning state, but no mention (that I can find) in the paper - am I correct in assuming the next token prediction weight was set to 0? (apologies for bugging you on this stuff!)