I've been lurking on LW since 2013, but only started posting recently. My day job was "analytics broadly construed" although I'm currently exploring applied prio-like roles; my degree is in physics; I used to write on Quora and Substack but stopped, although I'm still on the EA Forum. I'm based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Posts

Wiki Contributions

Comments

Holden advised against this:

Jog, don’t sprint. Skeptics of the “most important century” hypothesis will sometimes say things like “If you really believe this, why are you working normal amounts of hours instead of extreme amounts? Why do you have hobbies (or children, etc.) at all?” And I’ve seen a number of people with an attitude like: “THIS IS THE MOST IMPORTANT TIME IN HISTORY. I NEED TO WORK 24/7 AND FORGET ABOUT EVERYTHING ELSE. NO VACATIONS."

I think that’s a very bad idea.

Trying to reduce risks from advanced AI is, as of today, a frustrating and disorienting thing to be doing. It’s very hard to tell whether you’re being helpful (and as I’ve mentioned, many will inevitably think you’re being harmful).

I think the difference between “not mattering,” “doing some good” and “doing enormous good” comes down to how you choose the job, how good at it you are, and how good your judgment is (including what risks you’re most focused on and how you model them). Going “all in” on a particular objective seems bad on these fronts: it poses risks to open-mindedness, to mental health and to good decision-making (I am speaking from observations here, not just theory).

That is, I think it’s a bad idea to try to be 100% emotionally bought into the full stakes of the most important century - I think the stakes are just too high for that to make sense for any human being.

Instead, I think the best way to handle “the fate of humanity is at stake” is probably to find a nice job and work about as hard as you’d work at another job, rather than trying to make heroic efforts to work extra hard. (I criticized heroic efforts in general here.)

I think this basic formula (working in some job that is a good fit, while having some amount of balance in your life) is what’s behind a lot of the most important positive events in history to date, and presents possibly historically large opportunities today.

Also relevant are the takeaways from Thomas Kwa's effectiveness as a conjunction of multipliers, in particular:

- It's more important to have good judgment than to dedicate 100% of your life to an EA project. If output scales linearly with work hours, then you can hit 60% of your maximum possible impact with 60% of your work hours. But if bad judgment causes you to miss one or two multipliers, you could make less than 10% of your maximum impact. (But note that working really hard can sometimes enable multipliers-- see this comment by Mathieu Putz.)

- Aiming for the minimum of self-care is dangerous.

Amateur hour question, if you don't mind: how does your "future of AI teams" compare/contrast with Drexler's CAIS model?

You might also be interested in Scott's 2010 post warning of the 'next-level trap' so to speak: Intellectual Hipsters and Meta-Contrarianism

A person who is somewhat upper-class will conspicuously signal eir wealth by buying difficult-to-obtain goods. A person who is very upper-class will conspicuously signal that ey feels no need to conspicuously signal eir wealth, by deliberately not buying difficult-to-obtain goods.

A person who is somewhat intelligent will conspicuously signal eir intelligence by holding difficult-to-understand opinions. A person who is very intelligent will conspicuously signal that ey feels no need to conspicuously signal eir intelligence, by deliberately not holding difficult-to-understand opinions.

...

Without meaning to imply anything about whether or not any of these positions are correct or not3, the following triads come to mind as connected to an uneducated/contrarian/meta-contrarian divide:

- KKK-style racist / politically correct liberal / "but there are scientifically proven genetic differences"

- misogyny / women's rights movement / men's rights movement

- conservative / liberal / libertarian4

- herbal-spiritual-alternative medicine / conventional medicine / Robin Hanson

- don't care about Africa / give aid to Africa / don't give aid to Africa

- Obama is Muslim / Obama is obviously not Muslim, you idiot / Patri Friedman5

What is interesting about these triads is not that people hold the positions (which could be expected by chance) but that people get deep personal satisfaction from arguing the positions even when their arguments are unlikely to change policy6 - and that people identify with these positions to the point where arguments about them can become personal.

If meta-contrarianism is a real tendency in over-intelligent people, it doesn't mean they should immediately abandon their beliefs; that would just be meta-meta-contrarianism. It means that they need to recognize the meta-contrarian tendency within themselves and so be extra suspicious and careful about a desire to believe something contrary to the prevailing contrarian wisdom, especially if they really enjoy doing so.

In Bostrom's recent interview with Liv Boeree, he said (I'm paraphrasing; you're probably better off listening to what he actually said)

- p(doom)-related

- it's actually gone up for him, not down (contra your guess, unless I misinterpreted you), at least when broadening the scope beyond AI (cf. vulnerable world hypothesis, 34:50 in video)

- re: AI, his prob. dist. has 'narrowed towards the shorter end of the timeline - not a huge surprise, but a bit faster I think' (30:24 in video)

- also re: AI, 'slow and medium-speed takeoffs have gained credibility compared to fast takeoffs'

- he wouldn't overstate any of this

- contrary to people's impression of him, he's always been writing about 'both sides' (doom and utopia)

- e.g. his Letter from Utopia first published in 2005,

- in the past it just seemed more pressing to him to call attention to 'various things that could go wrong so we could avoid these pitfalls and then we'd have plenty of time to think about what to do with this big future'

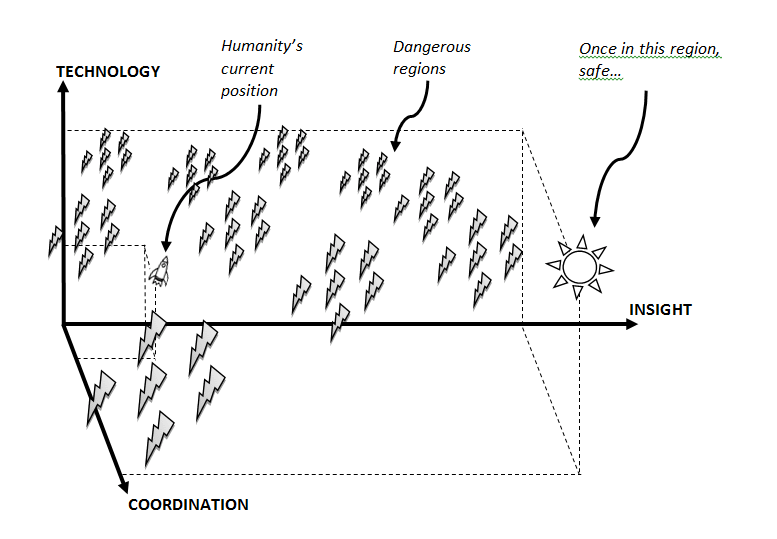

- this reminded me of this illustration from his old paper introducing the idea of x-risk prevention as global priority:

What's your take on Scott's post?

If I take this claimed strategy as a hypothesis (that radical introspective speedup is possible and trainable), how might I falsify it? I ask because I can already feel myself wanting to believe it's true and personally useful, which is an epistemic red flag. Bonus points if the falsification test isn't high cost (e.g. I don't have to try it for years).

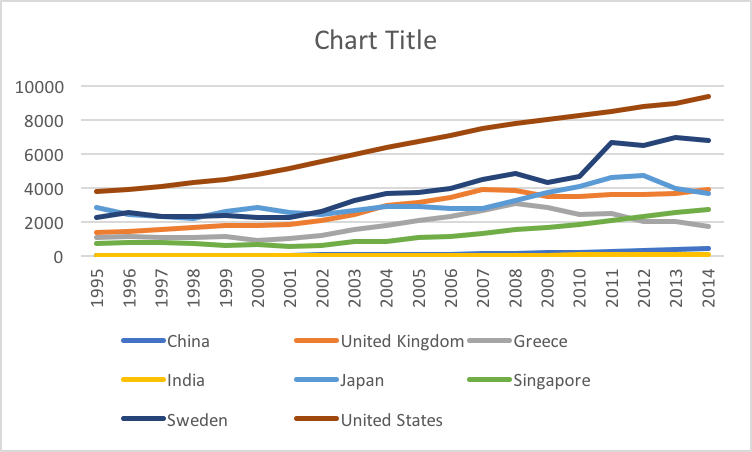

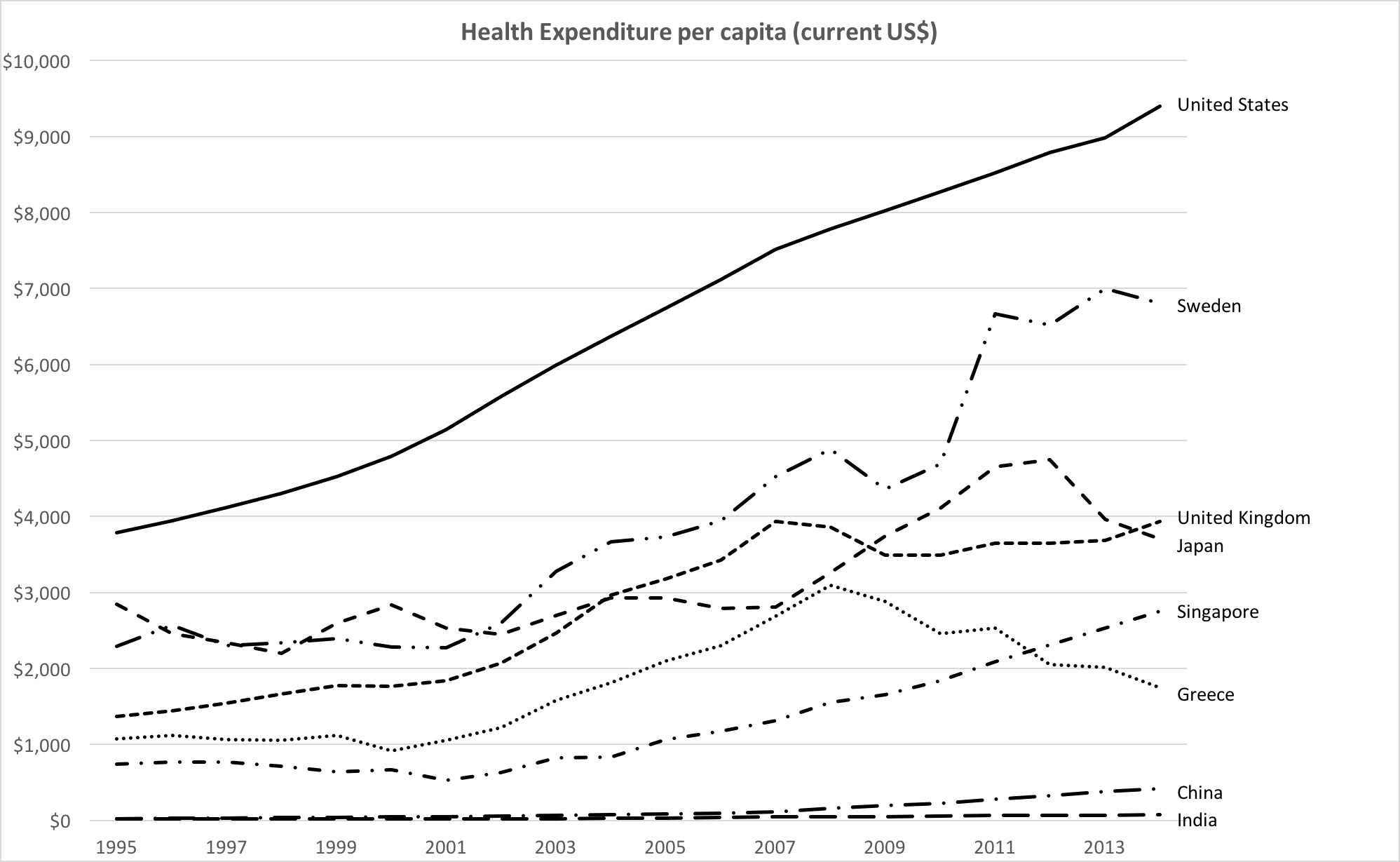

I was wondering about this too. I thought of Eugene Wei writing about Edward Tufte's classic book The Visual Display of Quantitative Information, which he considers "[one of] the most important books I've read". He illustrates with an example, just like dynomight did above, starting with this chart auto-created in Excel:

Wei adds further commentary:

No issues for color blind users, but we're stretching the limits of line styles past where I'm comfortable. To me, it's somewhat easier with the colored lines above to trace different countries across time versus each other, though this monochrome version isn't terrible. Still, this chart reminds me, in many ways, of the monochromatic look of my old Amazon Analytics Package, though it is missing data labels (wouldn't fit here) and has horizontal gridlines (mine never did).

We're running into some of these tradeoffs because of the sheer number of data series in play. Eight is not just enough, it is probably too many. Past some number of data series, it's often easier and cleaner to display these as a series of small multiples. It all depends on the goal and what you're trying to communicate.

At some point, no set of principles is one size fits all, and as the communicator you have to make some subjective judgments. For example, at Amazon, I knew that Joy wanted to see the data values marked on the graph, whenever they could be displayed. She was that detail-oriented. Once I included data values, gridlines were repetitive, and y-axis labels could be reduced in number as well.

Tufte advocates reducing non-data-ink, within reason, and gridlines are often just that. In some cases, if data values aren't possible to fit onto a line graph, I sometimes include gridlines to allow for easy calculation of the relative ratio of one value to another (simply count gridlines between the values), but that's an edge case.

For sharp changes, like an anomalous reversal in the slope of a line graph, I often inserted a note directly on the graph, to anticipate and head off any viewer questions. For example, in the graph above, if fewer data series were included, but Greece remained, one might wish to explain the decline in health expenditures starting in 2008 by adding a note in the plot area near that data point, noting the beginning of the Greek financial crisis (I don't know if that's the actual cause, but whatever the reason or theory, I'd place it there).

If we had company targets for a specific metric, I'd note those on the chart(s) in question as a labeled asymptote. You can never remind people of goals often enough.

And I thought, okay, sounds persuasive and all, but also this feels like Wei/Tufte is pushing their personal aesthetic on me, and I can't really tell the difference (or whether it matters).

I'm curious about you not doing these, since I'd unquestioningly accepted them, and would love for you to elaborate:

- save lots of money in a retirement account and buy index funds

- shower daily

- use shampoo

- wear shoes

- walk

Regarding 'diet stuff', I mostly agree and like how Jay Daigle put it:

I’ve decided lately that people regularly get confused, on a number of subjects, by the difference between science and engineering. ... Tl;dr: Science is sensitive and finds facts; engineering is robust and gives praxes. Many problems happen when we confuse science for engineering and completely modify our praxis based on the result of a couple of studies in an unsettled area. ...

This means two things. First is that we need to understand things much better for engineering than for science. In science it’s fine to say “The true effect is between +3 and -7 with 95% probability”. If that’s what we know, then that’s what we know. And an experiment that shrinks the bell curve by half a unit is useful. For engineering, we generally need to have a much better idea of what the true effect is. (Imagine trying to build a device based on the information that acceleration due to gravity is probably between 9 and 13 m/s^2).

Second is that science in general cares about much smaller effects than engineering does. It was a very long time before engineering needed relativistic corrections due to gravity, say. A fact can be true but not (yet) useful or relevant, and then it’s in the domain of science but not engineering.

Why does this matter?

The distinction is, I think fairly clear when we talk about physics. ... But people get much more confused when we move over to, say, psychology, or sociology, or nutrition. Researchers are doing a lot of science on these subjects, and doing good work. So there’s a ton of papers out there saying that eggs are good, or eggs are bad, or eggs are good for you but only until next Monday or whatever.

And people have, often, one of two reactions to this situation. The first is to read one study and say “See, here’s the scientific study. It says eggs are bad for you. Why are you still eating eggs? Are you denying the science?” And the second reaction is to say that obviously the scientists can’t agree, and so we don’t know anything and maybe the whole scientific approach is flawed.

But the real situation is that we’re struggling to develop a science of nutrition. And that shit is hard. We’ve worked hard, and we know some things. But we don’t really have enough information to do engineering, to say “Okay, to optimize cardiovascular health you need to cut your simple carbs by 7%, eat an extra 10g of monounsaturated fats every day, and eat 200g of protein every Wednesday” or whatever. We just don’t know enough.

And this is where folk traditions come in. Folk traditions are attempts to answer questions that we need decent answers to, that have been developed over time, and that are presumably non-horrible because they haven’t failed obviously and spectacularly yet. A person who ate “Like my grandma” is probably on average at least as healthy as a person who tried to follow every trendy bit of scientistic nutrition advice from the past thirty years.

Nitpick that doesn't bear upon the main thrust of the article:

2021: Here’s a random weightlifter I found coming in at over 400kg, I don’t have his DEXA but let’s say somewhere between 300 and 350kgs of muscle.

More plausibly Josh Silvas weighs 220-ish kg, not 400 kg, and there's no way he has anywhere near 300+ kg of muscle. To contextualize, the heaviest WSM winners ever weighed around 200-210 kg (Hafthor, Brian); Brian in particular had a lean body mass of 156 kg back when he weighed 200 kg peaking for competition ('peaking' implies unsustainability), which is the highest DEXA figure I've ever found in years of following strength-related statistics.

For anyone who's curious, this is what Scott said, in reference to him getting older – I remember it because I noticed the same in myself as I aged too:

This was back in 2017.