MIRI's "The Problem" hinges on diagnostic dilution

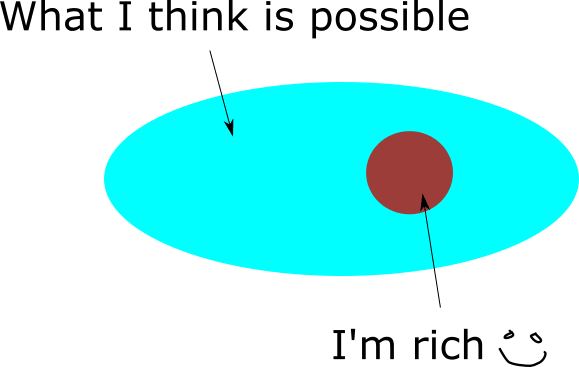

[adapted with significant technical improvements from https://clarifyingconsequences.substack.com/p/miris-ai-problem-hinges-on-equivocation, which I also wrote and will probably update to be more in line with this at some point] I'm going to meet someone new tomorrow, and I'm wondering how many kids they have. I know their number of kids is a nonnegative 32 bit integer, and almost all such numbers are greater than 1 million. So I suppose they're highly likely to have more than 1 million kids. This is an instance of a fallacy I'm calling diagnostic dilution[1]. It is akin to a probabilistic form of the fallacy of the undistributed middle. The error goes like this: we want to evaluate some outcome A given some information X. We note that X implies Y (or nearly so), and so we decide to evaluate P[A|Y]. But this is a mistake! Because X implies Y we are strictly better off evaluating P[A|X][2]. We've substituted a sharp condition for a vague one, hence the name diagnostic dilution. In the opening paragraph we have A="count > 1 million", X="we're counting kids" and Y="count is a nonnegative 32 bit integer". So P[A|X] is 0 and P[A|Y] is close to 1. Diagnostic dilution has lead us far astray. Diagnostic dilution is always structurally invalid, but it misleads us specifically when the conclusion hinges on forgetting X. "Bob is a practising doctor, so Bob can prescribe medications, so Bob can probably prescribe Ozempic" is a fine inference because it goes through without forgetting that Bob is a doctor. But consider the same chain starting with "Bob is a vet": now the inference does not go through unless we forget Bob's job, and indeed the conclusion is false. Diagnostic dilution is tricky because it looks a bit like a valid logical inference: X⟹Y and Y⟹A so X⟹A. But if P[A|Y] is even a hair less than 1, then, as we saw, we can end up being very wrong. > Quick definition: Diagnostic dilution is a probabilistic reasoning error that involves replacing the condition X with

I strongly disagree with this criterion! If a vision of the future tells us compellingly things like "future X is better than future Y (where both X and Y are plausible)" this is very valuable - we can use it to make plans, and our capacity to make plans is rising so it's OK to presently have ambitions that outstrip our capacity to see... (read more)