Several promising software engineers have asked me: Should I work at a frontier AI lab?

My answer is always “No.”

This post explores the fundamental problem with frontier labs, some of the most common arguments in favor of working at one, and why I don’t buy these arguments.

The Fundamental Problem

The primary output of frontier AI labs—such as OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta, and Google DeepMind—is research that accelerates the capabilities of frontier AI models and hastens the arrival of superhuman machines. Each lab’s emphasis on alignment varies, but none are on track to solve the hard problems, or to prevent these machines from growing irretrievably incompatible with human life. In the absence of an ironclad alignment procedure, frontier capabilities research accelerates the extinction of humanity. As a very strong default, I expect signing up to assist such research to be one of the gravest mistakes a person can make.

Some aspiring researchers counter: “I know that, but I want to do safety research on frontier models. I’ll simply refuse to work directly on capabilities.” Plans like these, while noble, dramatically misunderstand the priorities and incentives of scaling labs. The problem isn’t that you will be forced to work on capabilities; the problem is that the vast majority of safety work conducted by the labs enables or excuses continued scaling while failing to address the hard problems of alignment.

You Will Be Assimilated

AI labs are under overwhelming institutional pressure to push the frontier of machine learning. This pressure can distort everything lab employees think, do, and say.

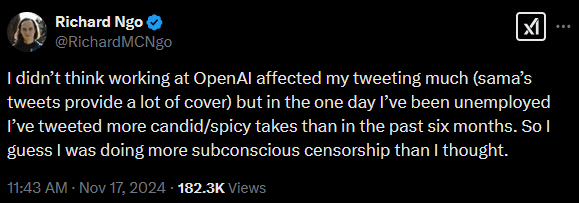

Former OpenAI Research Scientist Richard Ngo noticed this effect firsthand:

This distortion affects research directions even more strongly. It’s perniciously easy to "safetywash” despite every intention to the contrary.

The overlap between alignment and capabilities research compounds this effect. Many efforts to understand and control the outputs of machine learning models in the short term not only can be used to enhance the next model release, but are often immediately applied this way.

- Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) represented a major breakthrough for marketable chatbots.

- Scalable oversight, a popular component of alignment plans, fundamentally relies on building AIs that equal or surpass human researchers while alignment remains unsolved.

- Even evaluations of potentially dangerous capabilities can be hill-climbed in pursuit of marketable performance gains.

Mechanistic interpretability has some promising use cases, but it’s not a solution in the way that some have claimed, and it runs the risk of being applied to inspire algorithmic improvements. To the extent that future interpretability work could enable human researchers to deeply understand how neural networks function, it could also be used to generate efficiency boosts that aren’t limited to alignment research.

Make no mistake: Recursive self improvement leading to superintelligence is the strategic mandate of every frontier AI lab. Research that does not support this goal is strongly selected against, and financial incentives push hard for downplaying the long-term consequences of blindly scaling.

Right now, I don’t like anyone’s odds of a good outcome. I have on occasion been asked whose plan seems the most promising. I think this is the wrong question to ask. The plans to avert extinction are all terrible, when they exist at all. A better question is: Who is capable of noticing their efforts are failing, and will stop blindly scaling until their understanding improves? This is the test that matters, and every major lab fails it miserably.

If you join them, you likely will too.

The Arguments

Given the above, are there any lines of reasoning that might make a job at an AI lab net positive? Here, I attempt to address the strongest cases I’ve heard for working at a frontier lab.

Labs may develop useful alignment insights

The claim: Working at a major lab affords research opportunities that are difficult to find elsewhere. The ability to tinker with frontier models, the concentration of research talent, and the access to compute resources make frontier labs the best place to work on alignment before an AI scales to superintelligence.

My assessment: Labs like Anthropic and DeepMind indeed deserve credit for landmark work like Alignment Faking in Large Language Models and a significant portion of the world’s interpretability research.

I’m glad this research exists. All else equal, I’d like to see more of it. But all else is not equal. Massively more effort is directed at making AI more powerful and, to the extent that work of this kind can be used to advance capabilities, if that work is done at a lab, it will be used to advance capabilities.

Their alignment efforts strike me as too little, too late. No lab has outlined a workable approach to aligning smarter-than-human AI. They don’t seem likely to fix this before they get smarter-than-human AI. Their existing safety frameworks imply unreasonable confidence.

I don’t expect the marginal extra researcher to substantially improve these odds, even if they manage to resist the oppressive weight of subtle and unsubtle incentives.

Also, bear in mind that if the organization you choose does develop important alignment insights, you might be under strict binding agreement not to take them outside the company.

As labs scale, their models get more likely to become catastrophically dangerous. Massively more resources are required to get an aligned superintelligence than a merely functioning superintelligence, and the leading labs are devoting most of their resources to the second thing. As we don't and can't know where the precipice is, all of this work is net irresponsible and shouldn't be happening.

Insiders are better positioned to whistleblow

The claim: As research gets more secretive and higher stakes, and as more unshared models are used internally, it will be harder for both the safety community and the general public to know when a tipping point is reached. It may be valuable to the community as a whole to retain some talent on the inside that can sound the alarm at a critical moment.

My assessment: I’m sympathetic to the idea that someone should be positioned to sound the alarm if there are signs of imminent takeoff or takeover. But I have my doubts about the effectiveness of this plan, for broadly three reasons:

- Seniority gates access.

- You only get one shot.

- Clarions require clarity.

Seniority gates access. Labs are acutely aware of the risk of leaks, and I expect them to reserve key information for the eyes of senior researchers. I also expect access restrictions to rise with the stakes. Some people already at the labs do claim in private that they plan to whistleblow if they see an imminent danger. You are unlikely to surpass these people in access. Recall that these labs were (mostly) founded by safety-conscious people, and not all of them have left or fully succumbed to industry pressures.

You only get one shot. Whistleblowing is an extremely valuable service, but it’s not generally a repeatable one. Regulations might prevent labs from firing known whistleblowers, but they will likely be sidelined away from sensitive research. This means that a would-be whistleblower needs to think very carefully about exactly when and how to spend their limited capital, and that can mean delaying a warning until it’s too late to matter.

Clarions require clarity. There likely won’t be a single tipping point. For those with the eyes to recognize the danger, evidence abounds that frontier labs are taking on inordinate risk in their reckless pursuit of superintelligence. Given the strength of the existing evidence, it's hard to tell what policymakers or the general public might consider a smoking gun. That is, would-be-whistleblowers are forced to play a dangerous game of chicken, wherein to-them-obvious evidence of wrongdoing may, in fact, not be sufficiently legible to outsiders.

There’s a weaker version of this approach one could endorse. For example, applying to an AI lab with the intent to keep a finger on the pulse of progress and quietly alert allies of important developments. The benefits of such a path are even more questionable, however, and your leverage will remain limited by seniority, disclosure restrictions, and the value of the knowledge you can actually share.

(If you already work at a frontier lab, I still recommend pivoting. You should also be aware of the existence of AI Lab Watch as a resource for this and related decisions.)

Insiders are better positioned to steer lab behavior

The claim: Working within a lab can position a safety-conscious individual to influence the course of that lab’s decisions.

My assessment: I admit I have a hard time steelmanning this case. It seems straightforwardly true that no individual entering the field right now will be meaningfully positioned to slow the development of superhuman AI from inside a lab.

The pace is set by the most reckless driver. Many of the people who worked at OpenAI and who might be reasonably characterized as “safety-focused” ended up leaving for various reasons, whether to avoid bias and do better work elsewhere or because they weren’t getting enough support. Those who remain have a tight budget of professional capital, which they must manage carefully in order to retain their positions.

To effectively steer a scaling lab from the inside, you’d have to:

- Secure a position of influence in an organization already captured by an accelerationist paradigm;

- Avoid being captured yourself;

- Push an entire organization against the grain of its economic incentives; and

- Withstand the resulting backlash long enough to make a difference.

It seems clear to me that this game was already played, and the incentives won.

Lab work yields practical experience

The claim: Working at a scaling lab is the best way to gain expertise in machine learning [which can then be leveraged into solving the alignment problem].

My assessment: I used to buy this argument, before a coworker pointed out to me just how high the bar is for such work. Today, if you are hired by a frontier AI lab to do machine learning research, then odds are you are already competent enough to do high-quality research elsewhere.

AI labs have some of the most competitive hiring pipelines on the planet, chaotic hierarchies and team structures, high turnover rates, and limited opportunities for direct mentorship. This is not a good environment for upskilling.

Better me than the alternative

The claim: If I don’t work at a frontier lab, someone else will. I’m probably more safety-focused than the typical ML engineer at my skill level, so I can make a difference on the margin, and that’s the highest impact I can reasonably expect to have.

My assessment: This argument seems to rest on three key assumptions:

- You won’t do a better job than another ML engineer, so your work won’t meaningfully improve the capabilities frontier on the margin.

- Your work will meaningfully improve safety on the margin.

- Policy is doomed; there’s no better way for me to improve humanity’s odds outside the lab.

The first may well be true, though I wouldn’t want to put myself in a situation in which humanity’s future could depend on my not being too good at my job.

The second raises a clear followup question: How are you improving safety? As we’ve briefly discussed above, most opportunities to promote safety at frontier labs are not so promising. Alignment research at the labs is subject to intense pressure to serve the short-term needs of the business and its product; whistleblowing opportunities are rare at best; and attempting to steer the lab against the flow of its incentives hasn’t worked out well for those who tried.

The third is simply an unforced error. Many policymakers express their sincere concerns behind closed doors, the American public largely supports AI regulation, and a real or perceived crisis can drive rapid change. Dismissing a global halt as intractable is foolish and self-defeating; we can and should know better.

What to Do Instead?

Right now, the most urgent and neglected problems are in policy and technical governance. We need smart and concerned people thinking about what might work and preparing concrete proposals for the day when an opportunity arises to implement them. If this interests you, consider applying to orgs such as the AI Futures Project, MIRI, Palisade, NIST, RAND, an AISI, or another policy-focused organization with a need for technical talent.

If instead you're eager to apply an existing machine learning skillset to projects aimed at decreasing risk on the margin, you might consider METR, Apollo Research, Timaeus, Simplex, Redwood, or ARC. You might also take inspiration from, or look for ways to assist, Jacob Steinhardt’s work and Davidad's work at UK ARIA.

Regardless of skillset, however, my advice is to avoid any organization that’s explicitly trying to build AGI.