One thing that I find somewhat confusing is that the "time horizon"-equivalent for AIs reading blog posts seems so short. Like this is very vibes-y, but if I were to think of a question operationalized as "I read a blog post for X period of time, at what X would I think Claude has a >50% chance of identifying more central errors than I could?" intuitively it feels like X is very short. Well under an hour, and likely under 10 minutes.

This is in some sense surprising, since reading feels like a task they're extremely natively suited for, and on other tasks like programming their time horizons tend to be in multiple hours.

I don't have a good resolution to this.

"Most people make the mistake of generalizing from a single data point. Or at least, I do." - SA

When can you learn a lot from one data point? People, especially stats- or science- brained people, are often confused about this, and frequently give answers that (imo) are the opposite of useful. Eg they say that usually you can’t know much but if you know a lot about the meta-structure of your distribution (eg you’re interested in the mean of a distribution with low variance), sometimes a single data point can be a significant update.

This type of limited conclusion on the face of it looks epistemically humble, but in practice it's the opposite of correct. Single data points aren’t particularly useful when you know a lot, but they’re very useful when you have very little knowledge to begin with. If your uncertainty about a variable in question spans many orders of magnitude, the first observation can often reduce more uncertainty than the next 2-10 observations put together[1]. Put another way, the most useful situations for updating massively from a single data point are when you know very little to begin with.

For example, if an alien sees a human car for the first time, the alien can make massive updates on many different things regarding Earthling society, technology, biology and culture. Similarly, an anthropologist landing on an island of a previously uncontacted tribe can rapidly learn so much about a new culture from a single hour of peaceful interaction [2].

Some other examples:

- Your first day at a new job.

- First time visiting a country/region you previously knew nothing about. One afternoon in Vietnam tells you roughly how much things cost, how traffic works, what the food is like, languages people speak, how people interact with strangers.

- Trying a new fruit for the first time. One bite of durian tells you an enormous amount about whether you'll like durian.

- Your first interaction with someone's kid tells you roughly how old they are, how verbal they are, what they're like temperamentally. You went from "I know nothing about this child" to a working model.

Far from idiosyncratic and unscientific, these forms of "generalizing from a single data point" are just very normal, and very important, parts of normal human life and street epistemology.

This is the point that Douglas Hubbard tries to hammer in repeatedly over the course of his book (How to Measure Anything): You know less than you think you do, and a single measurement can be sometimes be a massive update.

[1] this is basically tautological from a high-entropy prior.

[2] I like Monolingual Fieldwork as a demonstration for the possibilities in linguistics: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sYpWp7g7XWU&t=2s

LLMs by default can easily be "nuance-brained", eg if you ask Gemini for criticism of a post it can easily generate 10 plausible-enough reasons of why the argument is bad. But recent Claudes seem better at zeroing in on central errors.

Here's an example of Gemini trying pretty hard and getting close enough to the error but not quite noticing it until I hinted it multiple times.

base rates, man, base rates.

Recent generations of Claude seem better at understanding and making fairly subtle judgment calls than most smart humans. These days when I’d read an article that presumably sounds reasonable to most people but has what seems to me to be a glaring conceptual mistake, I can put it in Claude, ask it to identify the mistake, and more likely than not Claude would land on the same mistake as the one I identified.

I think before Opus 4 this was essentially impossible, Claude 3.xs can sometimes identify small errors but it’s a crapshoot on whether it can identify central mistakes, and certainly not judge it well.

It’s possible I’m wrong about the mistakes here and Claude’s just being sycophantic and identifying which things I’d regard as the central mistake, but if that’s true in some ways it’s even more impressive.

Interestingly, both Gemini and ChatGPT failed at these tasks.

For clarity purposes, here are 3 articles I recently asked Claude to reassess (Claude got the central error in 2/3 of them). I'm also a little curious what the LW baseline is here; I did not include my comments in my prompts to Claude.

https://terrancraft.com/2021/03/21/zvx-the-effects-of-scouting-pillars/

https://www.clearerthinking.org/post/what-can-a-single-data-point-teach-you

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/vZcXAc6txvJDanQ4F/the-median-researcher-problem-1

EDIT: I ran some more trials, and i think the more precise summary is that Claude 4.6s can usually get the answer with one hint, while Geminis and other models often require multiple much more leading hints (and sometimes still doesn't get it)

It's all relative. I think my article is more moderate than say some of the intros on LW but more aggressive/direct than say Kelsey Piper's or Daniel Eth's intros, and maybe on par with dynomight's (while approaching it from a very different angle).

You might also like those articles more; ironically from my perspective I deliberately crafted this article to drop many signifiers of uncertainty that is more common in my natural speech/writing, on the theory that it's more pleasant/enjoyable to read.

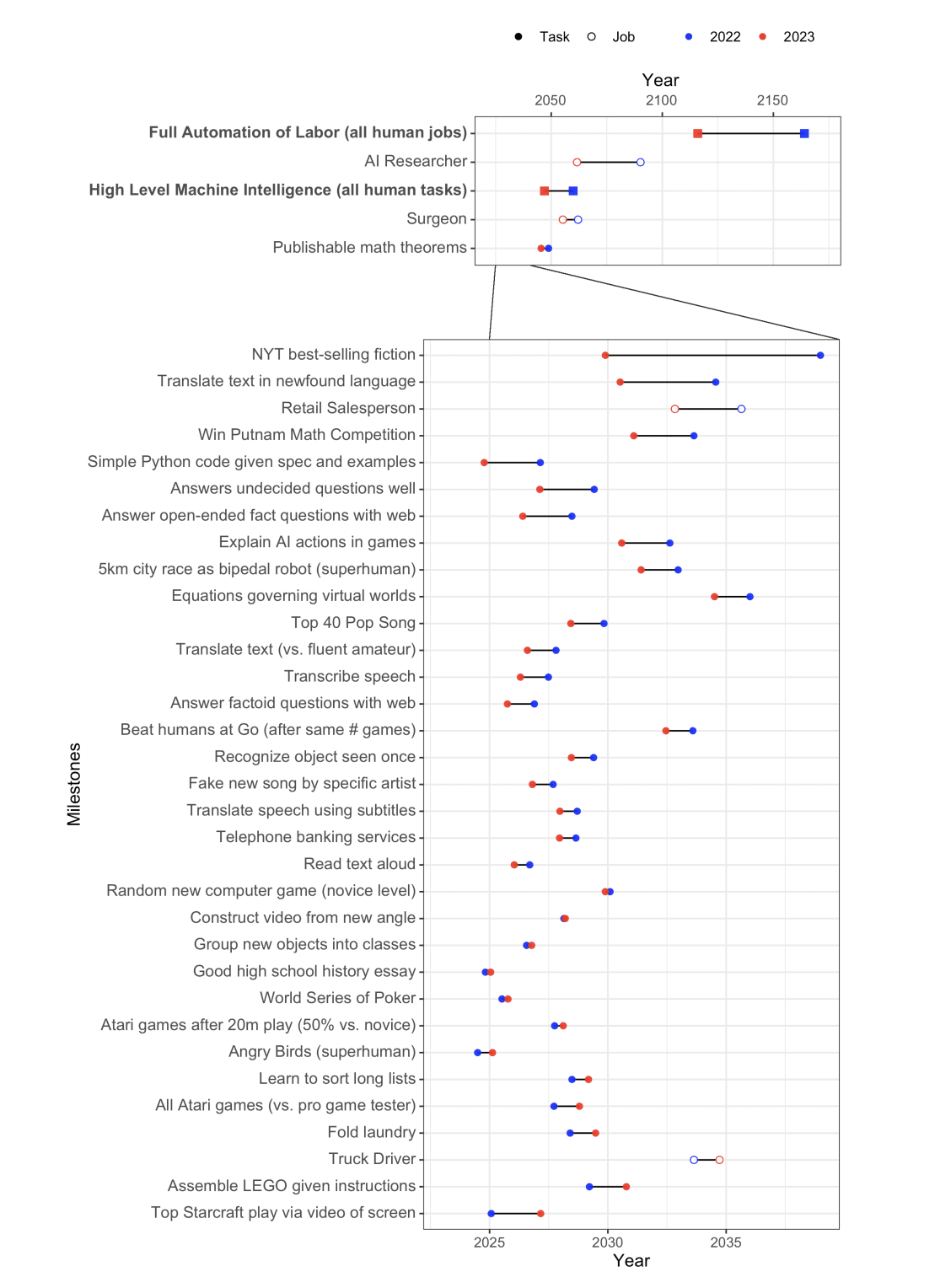

The graphs are a bit difficult to read, but see figure 2 here. Note that this is the writeup of the 2023 Grace et.al survey that also includes answers from the 2022 survey (In 2023 there's a large jump backwards in timelines across the board, which is to be expected).

I didn't include the source in the main article because I was worried it'd be annoying to parse, and explaining this is hard (not very hard, just that it requires more than one sentence and a link and I was trying to be economic in my opening).

I like Scott's Mistake Theory vs Conflict Theory framing, but I don't think this is a complete model of disagreements about policy, nor do I think the complete models of disagreement will look like more advanced versions of Mistake Theory + Conflict Theory.

To recap, here's my short summaries of the two theories:

Mistake Theory: I disagree with you because one or both of us are wrong about what we want, or how to achieve what we want)

Conflict Theory: I disagree with you because ultimately I want different things from you. The Marxists, who Scott was originally arguing against, will natively see this as about individual or class material interests but this can be smoothly updated to include values and ideological conflict as well.

I polled several rationalist-y people about alternative models for political disagreement at the same level of abstraction of Conflict vs Mistake, and people usually got to "some combination of mistakes and conflicts." To that obvious model, I want to add two other theories (this list is incomplete).

First, consider Thomas Schelling's 1960 opening to Strategy of Conflict

The book has had a good reception, and many have cheered me by telling me they liked it or learned from it. But the response that warms me most after twenty years is the late John Strachey’s. John Strachey, whose books I had read in college, had been an outstanding Marxist economist in the 1930s. After the war he had been defense minister in Britain’s Labor Government. Some of us at Harvard’s Center for International Affairs invited him to visit because he was writing a book on disarmament and arms control. When he called on me he exclaimed how much this book had done for his thinking, and as he talked with enthusiasm I tried to guess which of my sophisticated ideas in which chapters had made so much difference to him. It turned out it wasn’t any particular idea in any particular chapter. Until he read this book, he had simply not comprehended that an inherently non-zero-sum conflict could exist. He had known that conflict could coexist with common interest but had thought, or taken for granted, that they were essentially separable, not aspects of an integral structure. A scholar concerned with monopoly capitalism and class struggle, nuclear strategy and alliance politics, working late in his career on arms control and peacemaking, had tumbled, in reading my book, to an idea so rudimentary that I hadn’t even known it wasn’t obvious.

I claim that this "rudimentary/obvious idea," that the conflict/cooperative elements of many human disagreements is structurally inseparable, is central to a secret third thing distinct from Conflict vs Mistake[1]. If you grok the "obvious idea," we can derive something like

Negotiation Theory(?): I have my desires. You have yours. I sometimes want to cooperate with you, and sometimes not. I take actions maximally good for my goals and respect you well enough to assume that you will do the same; however in practice a "hot war" is unlikely to be in either of our best interests.

In the Negotiation Theory framing, disagreement/conflict arises from dividing the goods in non-zerosum games. I think the economists/game theorists' "standard models" of negotiation theory is natively closer to "conflict theory" than "mistake theory." (eg, often their models assume rationality, which means the "can't agree to disagree" theorems apply). So disagreements are due to different interests, rather than different knowledge. But unlike Marxist/naive conflict theory, we see that conflicts are far from desired or inevitable, and usually there are better trade deals from both parties' lights than not coordinating, or war.

(Failures from Negotiation Theory's perspectives often centrally look like coordination failures, though the theory is broader than that and includes not being able to make peace with adversaries)/

Another framing that is in some ways a synthesis and in some ways a different view altogether that can sit in each of the previous theories is a thing that many LW people talk about, but not exactly in this context:

Motivated Cognition: People disagree because their interests shape their beliefs. Political disagreements happen because one or both parties are mistaken about the facts, and those mistakes are downstream of material or ideological interests shading one's biases. Upton Sinclair: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

Note the word "difficult," not "impossible." This is Sinclair's view and I think it's correct. Getting people to believe (true) things against their material interests to believe is possible but the skill level required is higher than a neutral presentation of the facts to a neutral third party.

Interestingly, the Motivated Cognition framing suggests that there might not be a complete truth of the matter for whether "Mistake Theory" vs "Conflict Theory" vs Negotiation Theory is more correct for a given political disagreement. Instead, your preferred framing has a viewpoint-dependent and normative element to it.

Suppose your objective is just to get a specific policy passed (no meta-level preferences like altruism), and you believe this policy is in your interests and those of many others, and people who oppose you are factually wrong.

Someone who's suited to explanations like Scott (or like me?), might naturally fall into a Mistake Theory framing, and write clear-headed blogposts about why people who disagree with you are wrong. If the Motivated Cognition theory is correct, most people are at least somewhat sincere, and at some level of sufficiently high level of simplicity, people can update to agree with you even if it's not immediately in their interests (smart people in democracies usually don't believe 2+2=5 even in situations where it'd be advantageous for them to do so)

Someone who's good at negotiations and cooperative politics might more naturally adopt a Negotiation Theory framing, and come up with a deal that gets everybody (or enough people) what they want while having their preferred policy passed.

Finally, someone who's good at (or temperamentally suited to) non-cooperative politics and the more Machiavellian side of politics might identify the people who are most likely to oppose their preferred policies, and destroy their political influence enough that the preferred policy gets passed.

Anyway, here are my four models of political disagreement (Mistake, Conflict, Negotiation, Motivated Cognition). I definitely don't think these four models (or linear combinations of them) explain all disagreements, or are the only good frames for thinking of disagreement. Excited to hear alternatives [2]!

[1] (As I was writing this shortform, I saw another, curated, post comparing nonzero sum games against mistake vs conflict theory. I thought it was a fine post but it was still too much in the mistake vs conflict framing, whereas arguably in my eyes the nonzero sum game view is an entirely different way to view the world)

[2] In particular I'm wondering if there is a distinct case for ideological/memetic theories that operate along a similar level of abstraction as the existing theories, as opposed to thinking of ideologies as primarily given us different goals (which would make them slot in well with all the existing theories except Mistake Theory).

I find it very annoying when people give dismissals of technology trendlines because they don't have any credence in straight lines on a graph. Often people will post a meme like the following, or something even dumber.

I feel like it's really obvious why the two situations are dissimilar, but just to spell it out: the growth rate of human children is something we have overwhelming evidence for. Like literally we have something like 10 billion to 100 billion data points of extremely analogous situations against the exponential model.

And this isn't even including the animal data! Which should conservatively give you another 10-100x factor difference.

(This is merely if you're a base rates/forecasting chartist like me, and without even including physical and biological plausibility arguments).

So if someone starts with an exponential model of child growth, with appropriate error bars, they quickly update against it because they have something like > A TRILLION TO ONE EVIDENCE AGAINST.

But people think their arguments against Moore's Law, or AI scaling lows, or the METR time horizon curve, or w/e, merely because they don't believe in lines on a curve are sneaking in the assumption that "it definitely doesn't work" from a situation with a trillion to one evidence against on chartist grounds, plus physical plausibility arguments, when they have not in fact provided a trillion to one evidence against in their case.

wow thanks! It's the same point but he puts it better.