Steve Kommrusch has not written any posts yet.

Steve Kommrusch has not written any posts yet.

Thanks for the post, and especially the causal graph framework you use to describe and analyze the categories of motivations. It feels similar to Richard Dawkins 'The Selfish Gene' work in so far as it studies the fitness of motivations in their selection environment.

One area I think it could extend to is around the concepts of curiosity, exploration, and even corrigibility. This relates to 'reflection' as mentioned by habryka. I expect that as AI moves towards AGI it will improve its ability to recognize holes in its knowledge and take actions to close them (aka an AI scientist). Forming a world model that can be used for 'reflecting' on current motivations and... (read more)

Thanks for the interesting peak into your brain. I have a couple thoughts to share on how my own approaches relate.

The first is related to watching plenty of sci-fi apocalyptic future movies. While it's exciting to see the hero's adventures, I'd like to think that I'd be one of the scrappy people trying to hold some semblance of civilization together. Or the survivor trying to barter and trade with folks instead of fighting over stuff. In general, even in the face of doom, just trying to help minimize suffering unto the end. So the 'death with dignity' ethos fits in with this view.

A second relates to the idea of seeing yourself getting... (read more)

That idea of catching bad mesa-objectives during training sounds key and I presume fits under the 'generalization science' and 'robust character training' from Evan's original post. In the US, NIST is working to develop test, evaluation, verification and validation standards for AI and it would be good to include this concept into that effort.

The data relating exponential capabilities to Elo is seen over decades in the computer chess history too. From the 1960s into the 2020's, while computer hardware advanced exponentially at 100-1000x per decade in performance (and SW for computer chess advanced too), Elo scores grew linearly at about 400x per decade, taking multiple decades to go from 'novice' to 'superhuman'. Elo scores have a tinge of exponential to them - a 400 point Elo advantage is about a 10:1 chance for the higher scored competitor to win, and an 800 point Elo is about 200:1, etc. It appears that the current HW/SW/dollar rate of growth towards AGI means the Elo relative to humans is increasing faster than 400 Elo/decade. And, of course, unlike computer chess, as AI Elo at 'AI development' approaches the level of a skilled human, we'll likely get a noticable increase in the rate of capability increase.

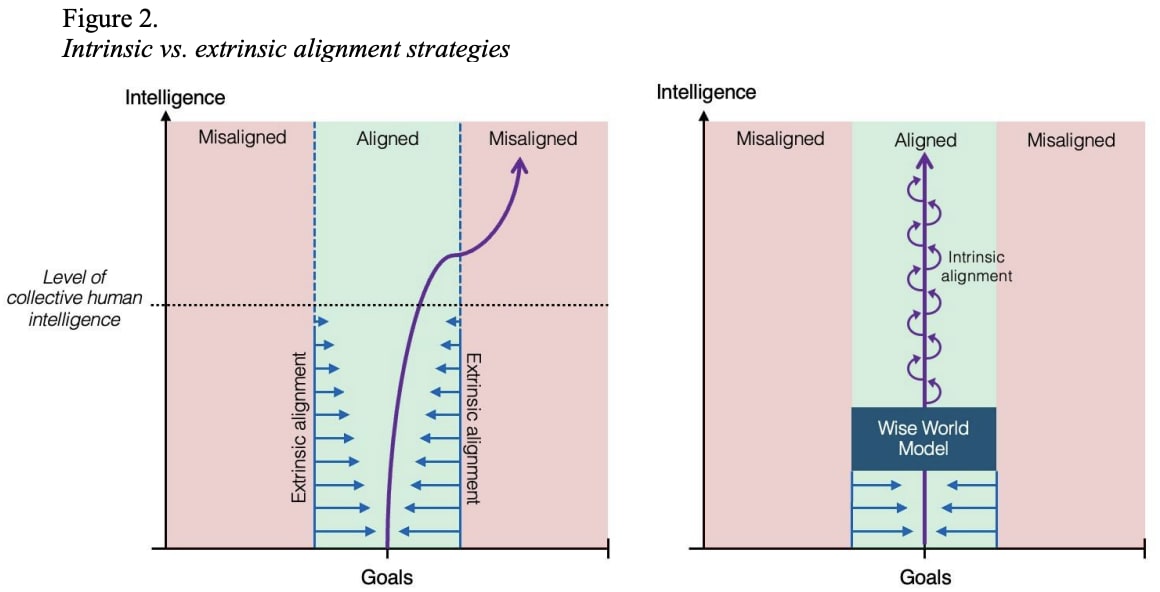

Thanks Evan for an excellent overview of the alignment problem as seen from within Anthropic. Chris Olah's graph showing perspectives on alignment difficulty is indeed a useful visual for this discussion. Another image I've shared lately relates to the challenge of building inner alignment illustrated by figure 2 from Contemplative Artificial Intelligence:

In the images, the blue arrows indicate our efforts to maintain alignment on AI as capabilities advance through AGI to ASI. In the left image, we see the case of models that generalize in misaligned ways - the blue constraints (guardrails, system prompts, thin efforts at RLHF, etc) fail to constrain the advancing AI to remain aligned. The right image shows... (read more)

I concur with that sentiment. GPUs hit a sweet spot between compute efficiency and algorithmic flexibility. CPUs are more flexible for arbitrary control logic, and custom ASICs can improve compute efficiency for a stable algorithm, but GPUs are great for exploring new algorithms where SIMD-style control flows exist (SIMD=single instruction, multiple data).

I would include "constructivist learning" in your list, but I agree that LLMs seem capable of this. By "constructivist learning" I mean a scientific process where the learning conceives of an experiment on the world, tests the idea by acting on the world, and then learns from the result. A VLA model with incremental learning seems close to this. RL could be used for the model update, but I think for ASI we need learnings from real-world experiments.

This post provides a good overview of some topics I think need attention by the 'AI policy' people at national levels. AI policy (such as the US and UK AISI groups) has been focused on generative AI and recently agentic AI to understand near-term risks. Whether we're talking LLM training and scaffolding advances, or a new AI paradigm, there is new risk when AI begins to learn from experiments in the world or reasoning about its own world model. In child development, imitation learning focuses on learning from examples, while constructivist learning focuses on learning by reflecting on interactions with the world. Constructivist learning is, I expect, key to push past AGI... (read 376 more words →)

From what I gather reading the ACAS X paper, it formally proved a subset of the whole problem and many issues uncovered by using the formal method were further analyzed using simulations of aircraft behaviors (see the end of section 3.3). One of the assumptions in the model is that the planes react correctly to control decisions and don't have mechanical issues. The problem space and possible actions were well-defined and well-constrained in the realistic but simplified model they analyzed. I can imagine complex systems making use of provably correct components in this way but the whole system may not be provably correct. When an AI develops a plan, it could prefer to follow a provably safe path when reality can be mapped to a usable model reliably, and then behave cautiously when moving from one provably safe path to another. But the metric for 'reliable model' and 'behave cautiously' still require non-provable decisions to solve a complex problem.

Interesting - I too suspect that good world models will help with data efficiency. Even using the existing training paradigm where a lot of data is needed to get the generalization to work well, if an AI has a good internal world model it could generate usable synthetic examples for incremental training. For example, when a child sees a photo of some strange new animal from the side, the child likely surmises that the animal looks the same from the other side; if the photo only shows one eye, the child can imagine that looking head on into the animal's face it will have 2 eyes, etc. Because the child has a... (read more)