Ping pong computation in superposition

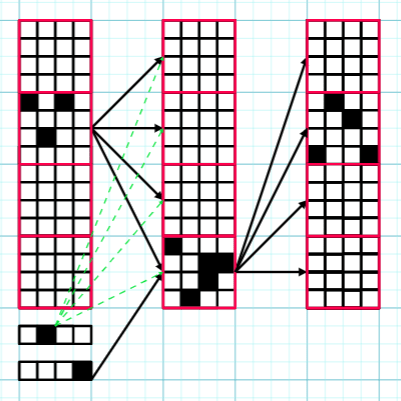

Overview: This post builds on Circuits in Superposition 2, using the same terminology. I focus on the z=1 case, meaning that exactly one circuit is active on each forward pass. This restriction simplifies the setting substantially and allows a construction with zero error, with T=D2d2 , L+2 layers, and width D(1+1d+⌈log2Dd⌉D). While the construction does not directly generalise to larger z, the strategy for mitigating error should still be relevant. I think the ideas behind the construction could be useful for larger z, and the construction itself is quite neat. Ping-Pong Trick for z=1: A circuit is specified by an ordered pair of memory blocks (the red squares). There are Ddmemory blocks, so D2d2 circuits can be coded for. The circuit is computed by "bouncing" between these two memory blocks. White squares represent neurons with no activation, and black squares represent neurons with any amount of activation. Green-dashed arrows represent the bias specific to block i. Here D=64, d=16. This is basically the same trick as ping-pong buffers. We divide the layer width D into Dd contiguous memory blocks of size d. We start with an input consisting of a vector x∈Rd, together with one-hot encodings of a pair of memory blocks (i,j). We initially load the input x into memory block i. Using a linear map applied to the one-hot encoding of memory block j, we add a massive negative bias to all blocks in the next layer except memory block j. This ensures that only memory block j can have neurons with non-zero activations in the following layer. Additionally, using a linear map applied to the one-hot encoding of i, we can freely set a size d bias b1(i,j) for the next layer's block j as a function of i (see the green arrows in the figure above). We are also free to pick the d×d linear map W1(i,j) between block i in the first layer and block j in the second layer. The end result is that when we run the network, all the blocks apart from block j in the second layer have 0

I don't care about prediction markets.

But people with the belief that we aren't going to be able to fully understand models frequently take this as a reason not to pursue ambitious/rigorous interpretability. I thought that was the position you were taking, by using the market to decide whether the agenda is "good" or not.