the method of estimating hardware vs software share seems biased in the direction of exaggerating hardware share. (because training compute and software efficiency both tend to increase over time, so doing a univariate regression on training compute will include some of the effect from software improvements. so subtracting off that coefficient from the total will underestimate the effect of software improvements / “algorithmic progress”.)

From the paper:

Comparing these two estimates allows us to decompose the total gain into hardware and software components. By subtracting the compute effect (0.048) from the total effect (0.083), we isolate a residual of 0.035. This residual represents algorithmic progress, an economic catch-all for improvements in model architecture, software optimization, and user learning—effectively the Solow residual of AI production. In percentage terms, this decomposition suggests that compute scaling drives approximately 56% of the total reduction in time, while algorithmic advancements account for the remaining 44%.

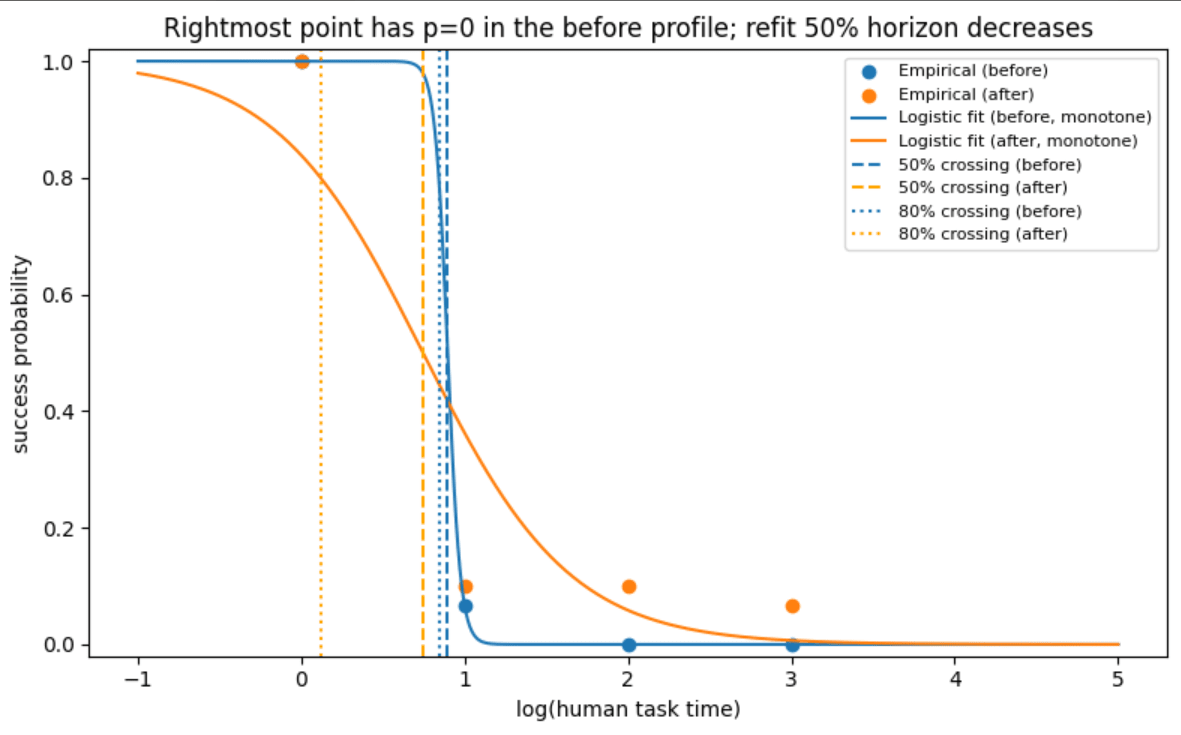

Yep! Here's an example where the 50% horizon and 80% horizon can be lower for an agent whose success profile dominates another agent (i.e. higher success rate at all task lengths), even for

(1) monotone nonincreasing success rates (i.e. longer tasks are harder)

(2) success rate of 1 at minimum task length

(3) success rate of 0 at maximum task length

before points are

[(0,1), (1, 1/15), (2, 0), (3,0)]

after points are

[(0,1), (1, 0.1), (2, 0.1), (3, 1/15)]

https://www.desmos.com/calculator/nqwn6ofmzq

Progress probably has sped up in the past couple of years. And training compute scaling has, if anything, slowed down (it hasn't accelerated, anyway). So yes, I think "software progress" probably has sped up in the past couple of years.

I haven't looked into whether you can see the algorithmic progress speedup in the ECI data using the methodology I was describing. The data would be very sparse if you e.g. tried to restrict to pre-2024 models for greater alignment with the Algorithmic Progress in Language Models paper, which is where the 3x per year number comes from.

Also, that 3x per year number is only measuring pre-training improvements. Post-training (1) didn't really exist before 2022 and (2) was notably accelerated in 2024 by the introduction of RLVR. I wouldn't be confident in whether pre-training algorithmic progress alone is much faster than 3x per year today. (as rumor would have it, there's substantial divergence between the different AGI companies on the rate of pretraining progress.)

Thanks!

There are a lot of parameters. Maybe this is necessary but it's a bit overwhelming and requires me to trust whoever estimated the parameters, as well as the modeling choices.

Yep. If you haven't seen already, we have a basic sensitivity analysis here. Some of the parameters matter much more than others. The five main sliders on the webpage correspond to the most impactful ones (for timelines as well as takeoff.) There are also some checkboxes in the Advanced Parameters section that let you disable certain features to simplify the model.

Regarding form factor / conciseness: thanks for the feedback! Seems like people have widely varying opinions here. Would you prefer a form factor like this to what we currently have? Would you prefer a Big Table of every equation plus a Big Table with every symbol to what we currently have? (by the way, I can't actually see the file Claude made --- maybe it would work if you shared the artifact rather than the conversation?)

Relating time horizon to coding automation speedup:

The only purpose of the time horizon in the model is to forecast the effective compute (which we would like to interpret as abstract "capability" or ECI or something) required for the Automated Coder milestone. You could do this in other ways, e.g. using Bio Anchors. (In fact, I would like to do it in other ways for more robustness, but sadly we didn't have time before the launch.)

We roll out the "human-only" trajectory to translate the current (release date, time horizon) trend into an (effective compute, time horizon) trend, then extrapolate that until the horizon reaches the AC requirement. This tells you the effective compute required for Automated Coder. This is then used to fit a separate automation schedule (which tells you the "fraction of coding tasks automated" at each effective compute level) which gets anchored to 100% at the AC effective compute value. (Another degree of freedom is pinned down to match our estimate of today's coding uplift). This automation fraction is used in a task-based CES model to compute the aggregate coding labor at each time, which is a pretty standard technique in economics for modeling automation, but not necessarily good. We think a more gears-level model of the delegation / reviewing / etc process of agentic coding would be more accurate, but again didn't come up with a fully-formed one in time. I'm curious to hear more about the data you're collecting on this!

Seems useful to talk to us in person about interpretations of time horizon / why 130 years is maybe reasonable. Eli's rationale for that estimate is written up here.

Why not assume that compute is allocated optimally between experiment, inference, etc. rather than assuming things about the behavior of AI companies?

As with many things in this project, we wish we had more time to look into it, but didn't prioritize it because we thought it would affect the results less than other things. When I briefly thought about this in the middle of the project, I remember getting confused about what "optimal" should mean. It also seems like it might increase the complexity of solving the model (it could increase the dimension of the system of differential equations, depending on how it's done.)

Messy digression on ways one might do this

For example, how do you decide how to allocate compute between experiments and training? If your goal is "maximize the effective compute of your frontier model at the end of the year", the optimal policy is to spend all of your compute on experiments now, then at some specific time switch to all-training. But setting a schedule of "deadlines" like this seems unnatural.

You could also imagine that at each point in time, the lab is spending an amortized "training budget" in H100e equaling

(size of actual frontier training system) x (fraction of each year during which it's utilized for training production models)

or

(company H100e) x (fraction of H100e in frontier training system) x (fraction of each year when it's utilized)

which is, assuming one frontier-scale production training run per year (which is maybe reasonable??):

(company H100e) x (fraction of H100e in frontier training system) x (min{1, training run length / 1 year}).

Jointly optimizing the FTS fraction, the training run length, and experiment compute seems like a bit of a mess, since the software efficiency that matters is probably the software efficiency at the beginning of the run, which you already decided at a previous timestep... possibly there's a nice solution to this. Might think about it more later today.

One thing I agree would be easy and I should probably do is plot the implied MRTS between experiment compute and automation compute over time, i.e. the number of experiment H100e you'd need to gain such that simultaneously losing a single automation H100e doesn't affect the software efficiency growth rate (or equivalently research effort). Theoretically this should always be 1. I bet it isn't though.

I wish the interface were faster to update, closer to 100ms than 1s to update, but this isn't a big deal. I can believe it's hard to speed up code that integrates these differential equations many times per user interaction.

Very interesting to hear! One main obstacle is that the model is being solved on the server rather than the client, so getting to 100ms is hard. There's also a tradeoff with time resolution (with very fast takeoffs, the graphs already look a bit piecewise linear.) But I think there is definitely room for optimization in the solver.

I think this is an interesting analysis. But it seems like you're updating more strongly on it than I am. Here are some thoughts.

The Forethought SIE model doesn't seem to apply well to this data:

In the Forethought model (without the ceiling add-on), the growth rate of "cognitive labor" is assumed to equal the growth rate of "software efficiency", which is in turn assumed to be proportional to the growth rate of cumulative "cognitive labor" (no matter the fixed level of compute). Whether this fooms or fizzles is determined only by whether this constant of proportionality is above or below 1.

In this framework, and with fixed experiment compute, the game is to find a trend for "software efficiency", then find a trend for cumulative "cognitive labor", then see which one is growing faster. So it matters quite a lot how you measure these two trends. (do you use the raw multiplier for software efficiency? or the number of OOMs? What about "cognitive labor"?)

It's worth stating that regardless of the value of , this model predicts that (in the right units) steady growth in cognitive labor (or cumulative cognitive labor) yields steady growth in software efficiency. (in the usual units, this means that the plot of log(2025-FLOP per FLOP) vs log(researcher-hours) is a straight line with slope .) A plot that curves downward or "hits a wall" seems like evidence against this model's applicability to the data. This could be due to ceiling effects (as habryka mentioned), or LoC being a poor proxy for researcher-hours (as Tao mentioned), or violation of the fixed-experiment-compute assumption, or other limitations of the model.

When I naively apply the Forethought SIE model to data on AGI labs, I get the opposite result:

Looking at OpenAI from January 2023[1] until today, I estimate that total headcount has grown at 2.3x per year,[2] while experiment compute available (in H100e) has grown at 3.7x per year. My median estimate of the rate of algorithmic progress over that time period is 10x/year[3] --- exceeding the growth rates of both inputs.[4] Naively applying the Forethought model, we can see that by a decent margin,[5] so I should expect that we're headed for a "software-only singularity". However...

I think the most important unknowns for takeoff speeds require splitting up the "cognitive labor" abstraction:

There are certain kinds of cognitive labor (e.g. writing code to implement ideas for research experiments) which are subject to compute bottlenecks --- in the sense that even with an unlimited quantity of (that kind of) labor, you would eventually be rate-limited by how many experiments (of unit compute scale) could be run at one time. See "Will Compute Bottlenecks Prevent a Software Intelligence Explosion?" (also by Davidson/Forethought!) for good discussion of this. If this were the only kind of "cognitive labor" which could meaningfully yield algorithmic progress, then my previous inference that we're headed for an SIE would be totally wrong.

There may be other kinds of useful cognitive labor which are not subject to compute bottlenecks, most prominently research taste / experiment selection skill. We tried to model this in the AI Futures Model. Unfortunately very little data exists on the relationship between algorithmic progress and research taste.[6] It's also unclear how quickly the research taste of automated researchers will improve compared to other capabilities.[7] The plausibility of a "taste-only singularity" (which currently controls most of my probability mass on very fast takeoffs) depends crucially on these quantities!

Cognitive quality of future AIs being so high that one hour of AIs researching is equivalent to exponentially large quantities of human researcher hours, even if they don't train much more efficiently to the same capability level. This is the most important question to answer and something I hope METR does experiments on in Q1.

I also hope METR does this!

- ^

Mainly because there is a trend break in the labor time series around the time ChatGPT was released, also because my algorithmic progress estimate is mostly based on post-2023 data.

- ^

The growth rate of research staff might be slower due to an increasing fraction of non-research (e.g. product, sales, marketing) staff post-2023. But it seems unlikely to be faster than the growth rate of the total.

- ^

I think ECI is the current best metric available for measuring algorithmic progress. The ECI paper does a bunch of different analyses which give different central estimates, all of which are above 3x/year (except for one in Appendix C.1.2, which the authors state introduces a downward bias.) My preferred method is doing a joint linear regression of ECI as a function of training compute and release date, than looking at the slope of the resulting "lines of constant ECI." Doing this on the whole data set gives ~20x/year; filtering to "non-distilled" models" gives a similar answer; filtering to only models which advanced the frontier of compute efficiency at release gives ~30x per year; filtering on both conditions gives more like 8x per year. Code for these analyses can be found here. It's unclear which of these is most applicable to the question of future software intelligence explosions, but it seems safe to say that 3x per year is too low. See also Aaron Scher's recent post "Catch-Up Algorithmic Progress Might Actually be 60x per Year".

- ^

It might be better to compare the rate of algorithmic progress specifically achieved by OpenAI to the growth rate of OpenAI compute and labor. The data is much sparser however, and I don't see a strong reason why it should differ in one direction or the other. It's also hard to separate out the effects of knowledge diffusion between labs. Alternatively I could use estimates for worldwide AGI-researcher labor growth rates and worldwide AGI-research compute growth rates. I am less certain about these as well.

- ^

The specific calculated value of would depend on the value of . If were 1 it would be log(10)/log(2.3) = 2.76; if were 0 it would be 1.76. If were in between, would be in between.

- ^

For the purposes of our forecast, we surveyed various AI researchers to estimate the multiplier on the rate of algorithmic progress corresponding to median vs top-human-level research taste, and got a central estimate of 3.7x. It would be better to do an actual experiment. (toy example: have many many many different AI researchers attempt something like the NanoGPT speedrun, but individually. measure the variance. Seems hard to do well.)

- ^

As measured by effect on takeoff speeds, this single parameter is where most of our uncertainty comes from. Our forecast looks at how quickly AI capabilities have moved through the human range in a bunch of different domains, and uses that as a reference class for an adjusted estimate. This is super uncertain.

Registering that I don't expect GPT-5 to be "the biggest model release of the year," for various reasons. I would guess (based on the cost and speed) that the model is GPT-4.1-sized. Conditional on this, the total training compute is likely to be below the state of the art.

For what it's worth, the model showcased in December (then called o3) seems to be completely different from the model that METR benchmarked (now called o3).

This is such a cool method! I am really curious about applying this method to Anthropic's models. Would you mind sharing the script / data you used?