I'm not sure it might result in a wake up of AI Researchers.

See this thread yesterday between Chris Painter and Dean Ball:

Chris: I have the sense that, as of the last 6 months, a lot of tech now thinks an intelligence explosion is more plausible than they did previously. But I don’t feel like I’m hearing a lot about that changing people’s minds on the importance of alignment and control research.

Dean: do people really think alignment and control research is unimportant? it seems like a big part of why opus is so good is the approach ant took to aligning it, and like basically everyone recognizes this?Chris: I’m not sure they think it’s unimportant. It’s more that around a year ago a lot of people would’ve said something like “Well, some people are really nervous about alignment and control research and loss of control etc, but that’s because they have this whole story of AI foom and really dramatic self-improvement. I think that story is way overstated, these models just don’t speed me up that much today, and I think we’ll have issues with autonomy for a long time, it’s really hard.” So, they often stated their objection in a way that made it sound like rapid progress on AI R&D automation would change their mind. To be clear, I think there are stronger objections that they could have raised and could still raise, like “we will then move to hardware bottlenecks, which will require AI proliferation for a true speed up to materialize”. Also, sorry if it’s rough for me to not be naming specific names, would just take time to pull examples.

Using @ryan_greenblatt's updated 5-month doubling time: we reach the 1-month horizon from AI 2027 in ~5 doublings (Jan 2028) at 50% reliability, and ~8 doublings (Apr 2029) at 80% reliability. If I understand correctly, your model uses 80% reliability while also requiring 30x cheaper and faster than humans. It does seem like if the trend holds, by mid-2029 the models wouldn't be much more expensive or slower. But I agree that if a lab tried to demonstrate "superhuman coder" on METR by the end of next year using expensive scaffolding / test-time compute (similar to o1 on ARC-AGI last year), it would probably exceed 30x human-cost, even if already 30x faster.

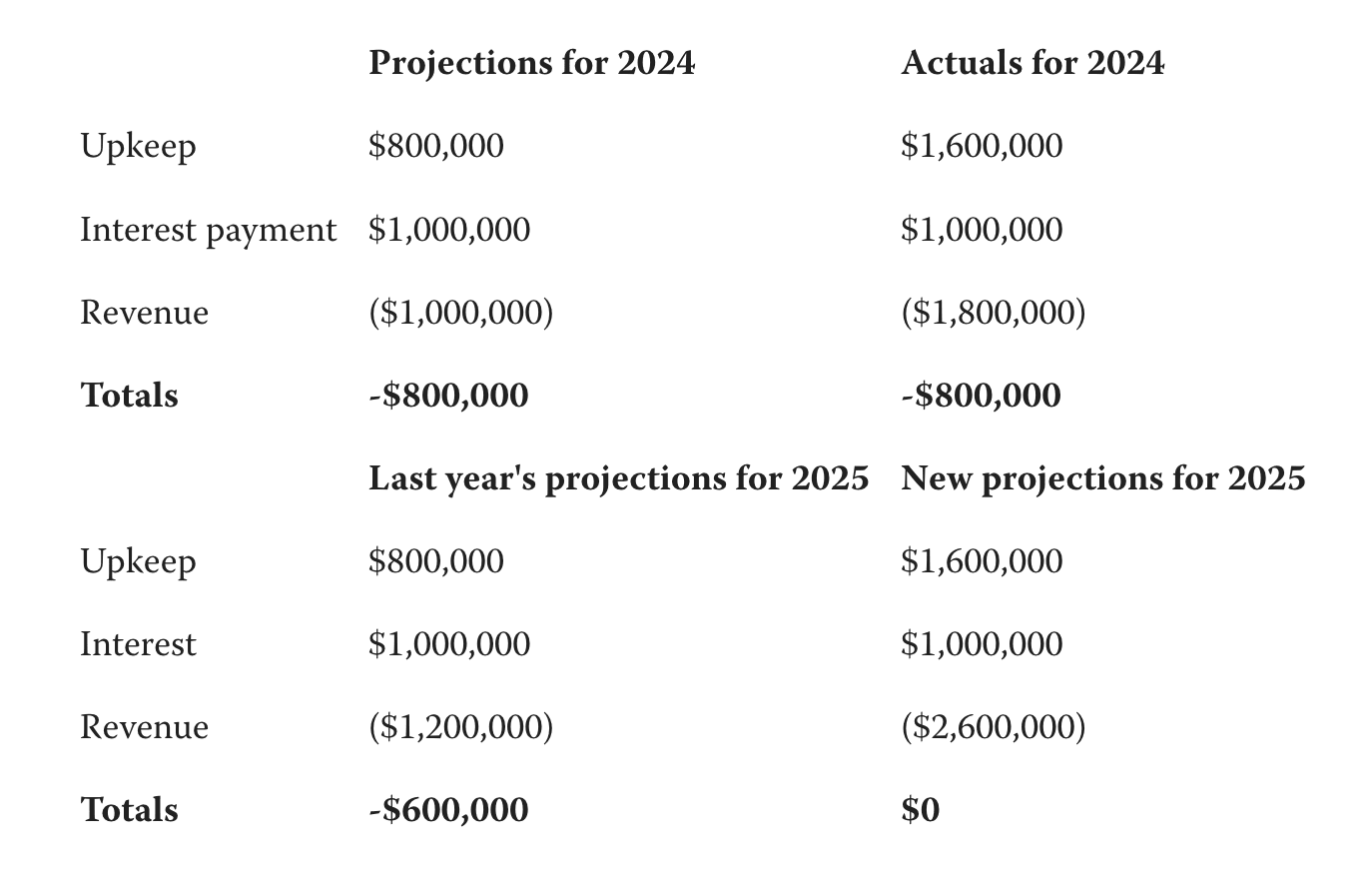

Any updates on the 2025 numbers for Lighthaven? (cf. this table from last year's fundraiser)

My guess at what's happening here: for the first iterations of MATS (think MATS 2.0 at the Lightcone WeWork) you would have folks who were already into AI Safety for quite a long time and were interested in doing some form of internship-like thing for a summer. But as you run more cohorts (and make the cohorts bigger) then the density of people who have been interested in safety for a long time naturally decreases (because all the people who were interested in safety for years already applied to previous iterations).

Congrats on the launch!

I would add the main vision for this (from the website) directly in the post as quoted text, so that people can understand what you're doing (& discuss).

I was trying to map out disagreements between people who are concerned enough about AI risk.

Agreed that this represents only a fraction of the people who talk about AI risk, and that there are a lot of people who will use some of these arguments as false justifications for their support of racing.

EDIT: as TsviBT pointed out in his comment, OP is actually about people who self-identify as members of the AI Safety community. Given that, I think that the two splits I mentioned above are still useful models, since most people I end up meeting who self-identify as members of the community seem to be sincere, without stated positions that differ from their actual reasons for why they do things. I have met people who I believe to be insincere, but I don't think they self-identify as part of the AI Safety community. I think that TsviBT's general point about insincerity in the AI Safety discourse is valid.

You make a valid point. Here's another framing that makes the tradeoff explicit:

- Group A) "Alignment research is worth doing even though it might provide cover for racing"

- Group B) "The cover problem is too severe. We should focus on race-stopping work instead"

Some questions I have:

1. Compute bottleneck

The model says experiment compute becomes the binding constraint once coding is fast. But are frontier labs actually compute-bottlenecked on experiments right now? Anthropic runs inference for millions of users while training models. With revenue growing, more investment coming in, and datacenters being built, couldn't they allocate eg. 2x more to research compute this year if they wanted?

2. Research taste improvement rate

The model estimates AI research taste improvement based on how quickly AIs have improved in a variety of metrics.

But researchers at a given taste level can now run many more experiments because Claude Code removes the coding bottleneck.

More experiment output means faster feedback, which in turn means faster taste development. So the rate at which human researchers develop taste should itself be accelerating. Does your model capture this? Or does it assume taste improvement is only a function of effective compute, not of experiment throughput?

3. Low-value code

Ryan's argument (from his October post) is that AI makes it cheap to generate code, so people generate more low-level code they wouldn't have otherwise written.

But here's my question: if the marginal code being written is "low-value" in the sense of "wouldn't have been worth a human's time before," isn't that still a real productivity gain, if say researchers can now run a bunch of claude code agents instances to run experiments instead of having to interface with a bunch of engineers?

4. What AIs Can't Do

The model treats research taste as qualitatively different from coding ability. But what exactly is the hard thing AIs can't do? If it's "generating novel ideas across disciplines" or "coming up with new architectures", these seem like capabilities that scale with knowledge and reasoning, both improving. IIRC there's some anecdotal evidence of novel discoveries of an LLM solving an Erdős problem, and someone from the Scott Aaronson sphere discussing AI contributions to something like quantum physics problems? Not sure.

If it's "making codebases more efficient", AIs already beat humans at competitive programming. I've seen some posts on LW discussing how they timed theirselves vs an AI against something that the AI should be able to do, and they beat the AI. But intuitively it does seem to me that models are getting better at the general "optimizing codebases" thing, even if it's not quite best-human-level yet.

5. Empirical basis for β (diminishing returns)

The shift from AI 2027 to the new model seems to come partly from "taking into account diminishing returns", aka the Jones model assumption that ideas get harder to find. What data did you use to estimate β? And given we're now in a regime with AI-assisted research, why should historical rates of diminishing returns apply going forward?