This is one of three sets of fixed point exercises. The first post in this sequence is here, giving context.

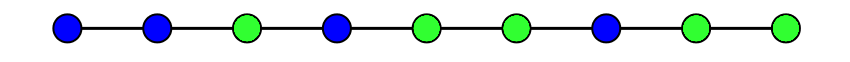

1. (1-D Sperner's lemma) Consider a path built out of n edges as shown. Color each vertex blue or green such that the leftmost vertex is blue and the rightmost vertex is green. Show that an odd number of the edges will be bichromatic.

2. (Intermediate value theorem) The Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem states that any bounded sequence in Rn has a convergent subsequence. The intermediate value theorem states that if you have a continuous function f:[0,1]→R such that f(0)≤0 and f(1)≥0, then there exists an x∈[0,1] such that f(x)=0. Prove the intermediate value theorem. It may be helpful later on if your proof uses 1-D Sperner's lemma and the Bolzano-Weierstrass theorem

3. (1-D Brouwer fixed point theorem) Show that any continuous function f:[0,1]→[0,1] has a fixed point (i.e. a point x∈[0,1] with f(x)=x). Why is this not true for the open interval (0,1)?

4. (2-D Sperner's lemma) Consider a triangle built out of n2 smaller triangles as shown. Color each vertex red, blue, or green, such that none of the vertices on the large bottom edge are red, none of the vertices on the large left edge are green, and none of the vertices on the large right edge are blue. Show that an odd number of the small triangles will be trichromatic.

5. Color the all the points in the disk as shown. Let f be a continuous function from a closed triangle to the disk, such that the bottom edge is sent to non-red points, the left edge is sent to non-green points, and the right edge is sent to non-blue points. Show that f sends some point in the triangle to the center.

6. Show that any continuous function f from closed triangle to itself has a fixed point.

7. (2-D Brouwer fixed point theorem) Show that any continuous function from a compact convex subset of R2 to itself has a fixed point. (You may use the fact that given any closed convex subset S of Rn, the function from Rn to S which proje

I have a feeling that something is missing from the Łukasiewicz stuff you've been doing because I don't think that assigning a quantitative degree of truth is all that vagueness really ought to be about. Vague sentences shift their meanings as the context changes. Vague statements can become crisp statements, and accordingly our language can gain more powerful synonymy. As a slogan perhaps, "vagueness wants to become ambiguity".