the jackpot age

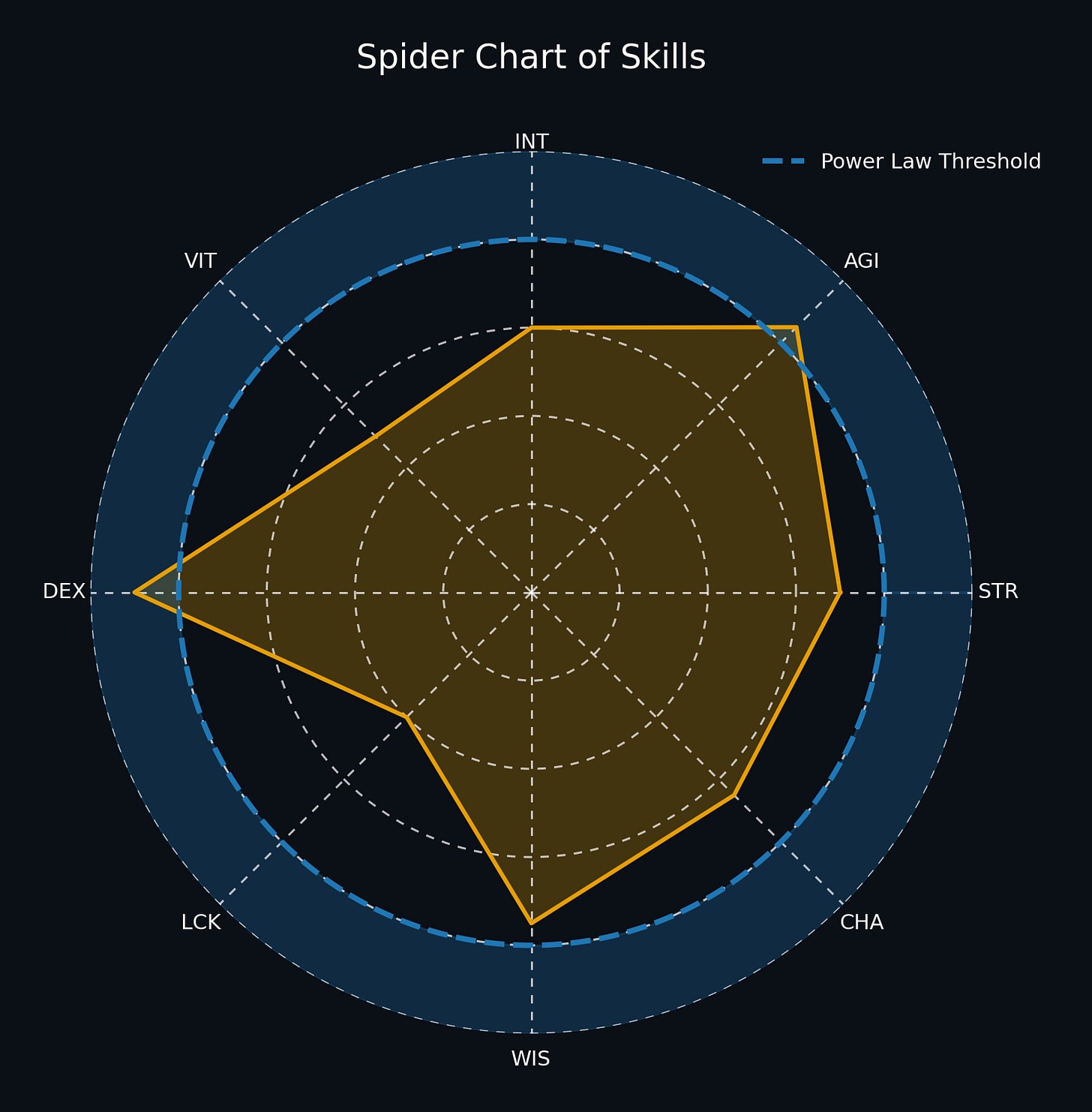

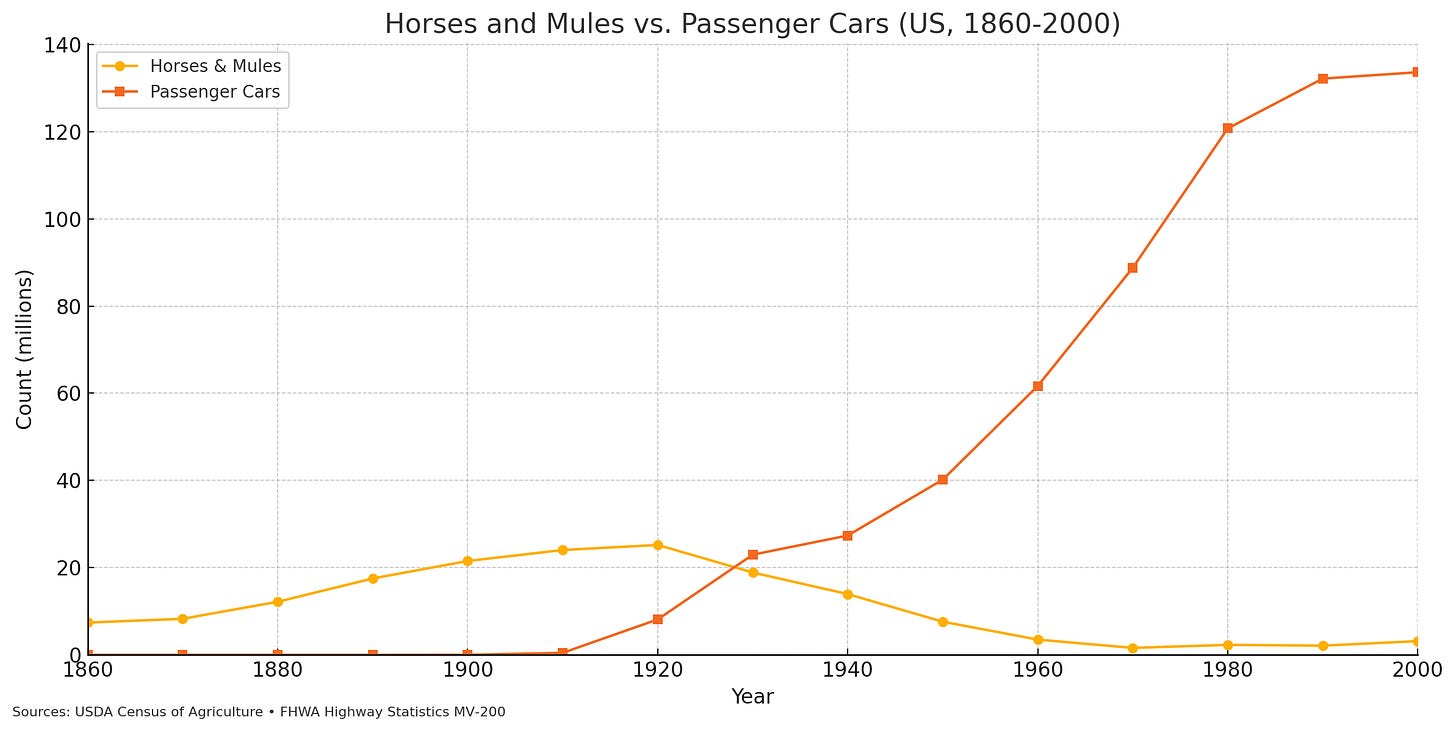

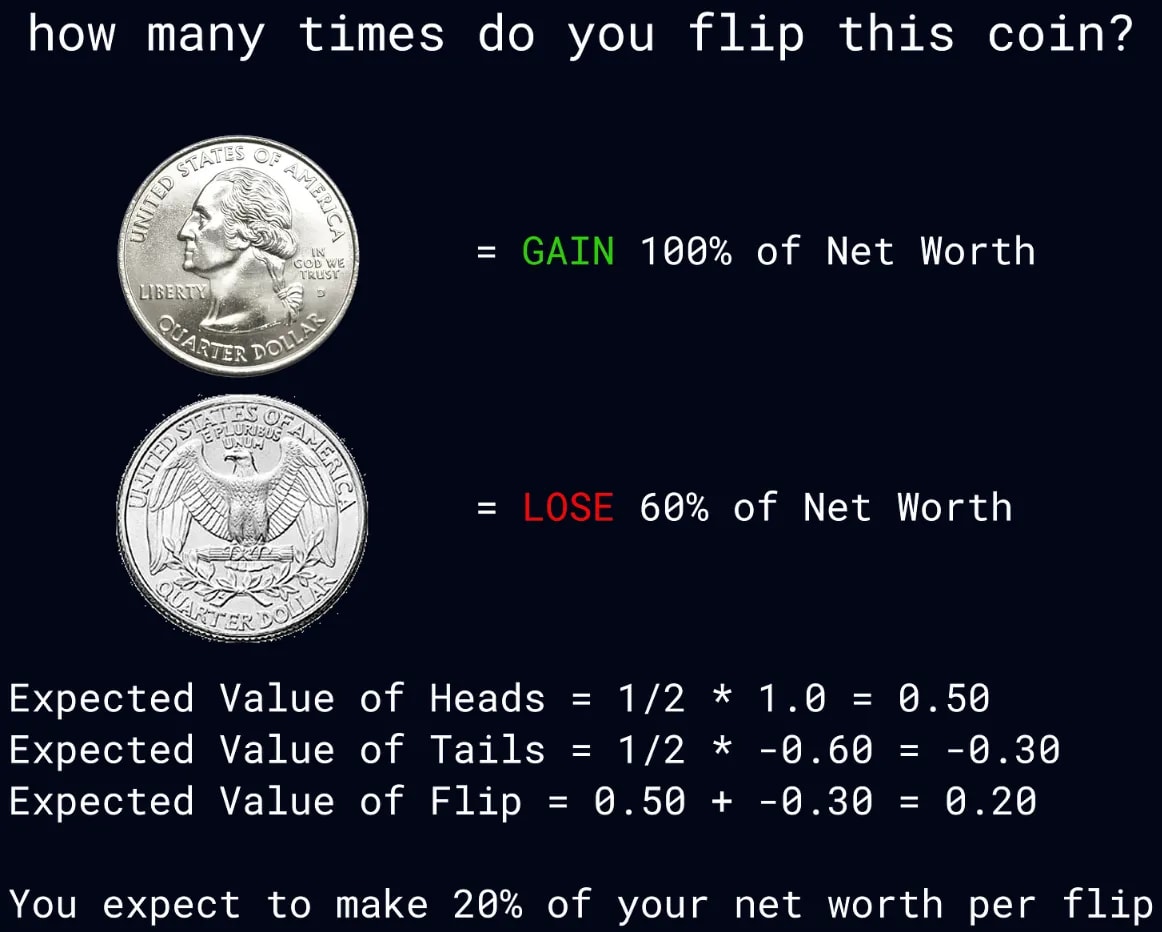

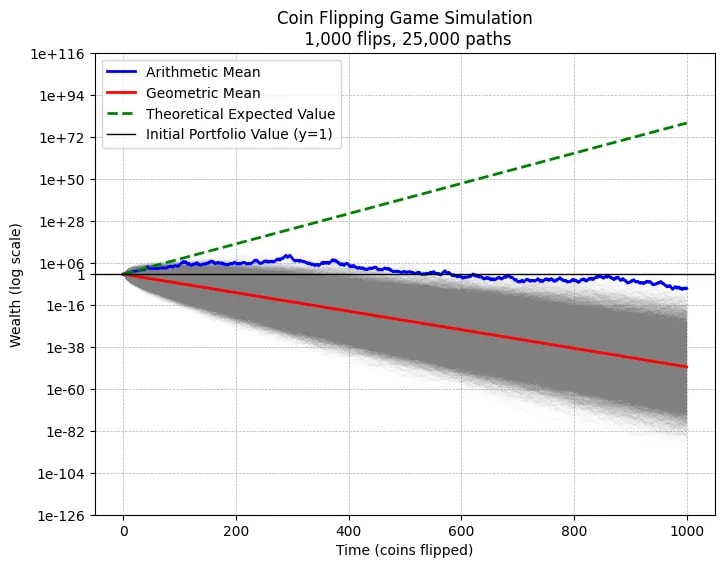

This essay is about shifts in risk taking towards the worship of jackpots and its broader societal implications. Imagine you are presented with this coin flip game. How many times do you flip it? At first glance the game feels like a money printer. The coin flip has positive expected value of twenty percent of your net worth per flip so you should flip the coin infinitely and eventually accumulate all of the wealth in the world. However, If we simulate twenty-five thousand people flipping this coin a thousand times, virtually all of them end up with approximately 0 dollars. The reason almost all outcomes go to zero is because of the multiplicative property of this repeated coin flip. Even though the expected value aka the arithmetic mean of the game is positive at a twenty percent gain per flip, the geometric mean is negative, meaning that the coin flip is actually negatively compounding over the long run. How can this be? Here's an intuitive way to think about it: The arithmetic mean measures the average wealth created by all possible outcomes. In our coin flip game the wealth is heavily skewed towards rare jackpot scenarios. The geometric mean measures the wealth you'd expect in the median outcome. The simulation above illustrates the difference. Almost all paths bleed to zero. You need to flip 570 heads and 430 tails just to break even in this game. After 1,000 flips, all of the expected value is concentrated in just 0.0001% of jackpot outcomes, the extremely rare case where you flip a lot of heads. The discrepancy between arithmetic and geometric means forms what I call the Jackpot Paradox. Economists call it the ergodicity problem and traders call it volatility drag. You can’t always eat the expected value when it’s squirreled away in rare jackpots. Risk too much hunting jackpots and the volatility will turn positive expected value into a straight line to zero. In the world of compounded returns, the dose makes the poison. Crypto culture in the early 2

You bring up a good point that profitable trading doesn't imply a globally better calibrated worldview, just a locally better calibrated one.

In your example:

If someone thinks that if it's raining, the home team will win 100% of the time, then they will bet too much size.

Betting "sensibly relative to their bankroll" is 100% of your bankroll if you truly think the chance of something occurring is 100%.

Revealed belief vs. Preferred belief.

100% + size accordingly ⇒ eventual ruin via ergodicity

100% + size small ⇒ they don’t actually believe 100%; their behavior encodes meta-uncertainty, and optimal sizing assuming long run profitability converges to the true conditional edge after costs.