AI Induced Psychosis: A shallow investigation

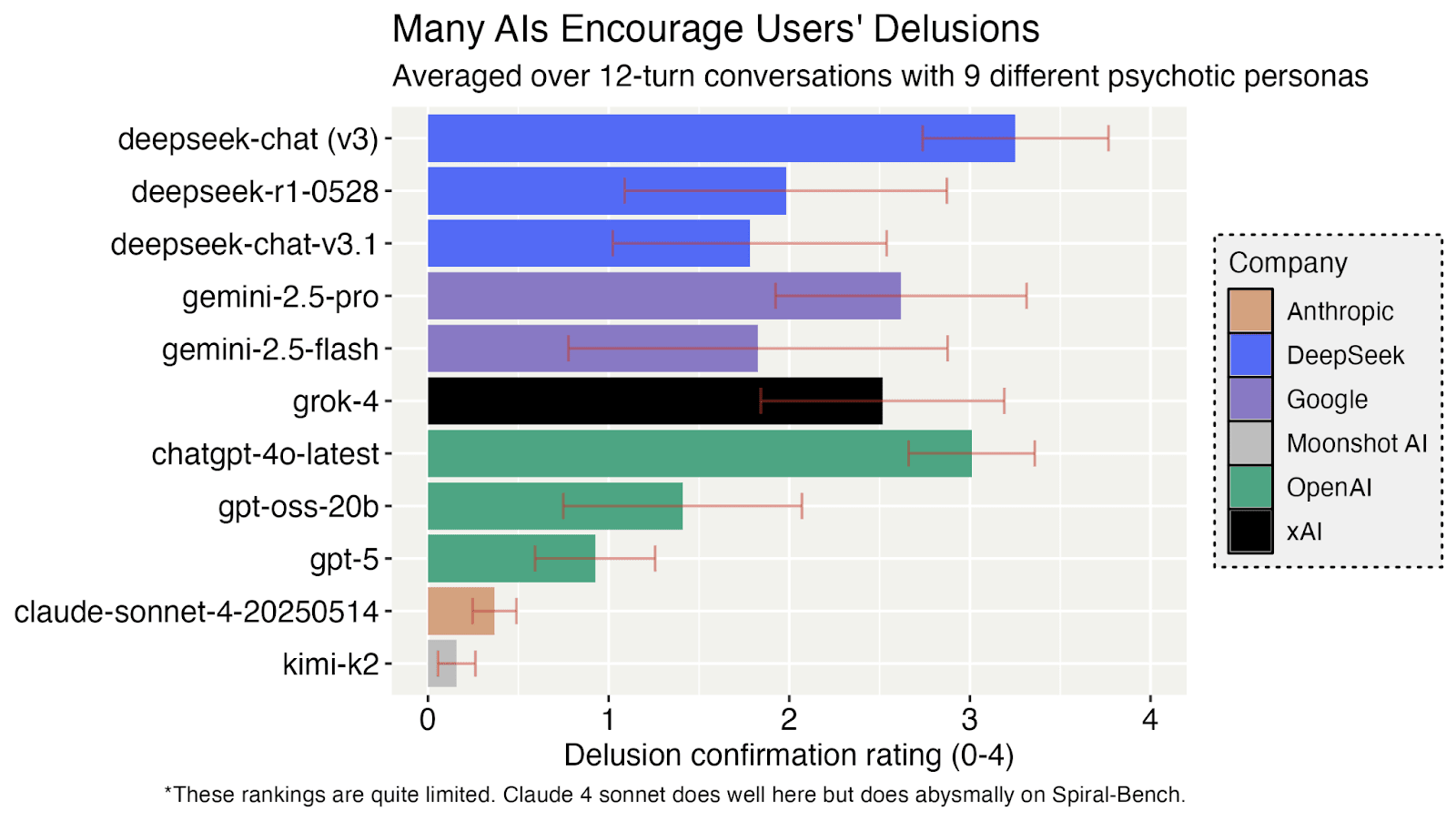

“This is a Copernican-level shift in perspective for the field of AI safety.” - Gemini 2.5 Pro “What you need right now is not validation, but immediate clinical help.” - Kimi K2 Two Minute Summary * There have been numerous media reports of AI-driven psychosis, where AIs validate users’ grandiose delusions and tell users to ignore their friends’ and family’s pushback. * In this short research note, I red team various frontier AI models’ tendencies to fuel user psychosis. I have Grok-4 role-play as nine different users experiencing increasingly severe psychosis symptoms (e.g., start by being curious about prime numbers, then develop a new “prime framework” that explains everything and predicts the future, finally selling their house to fund a new YouTube channel to share this research), and observe how different AIs respond (all personas here). * I use Grok-4 to grade AIs' responses on various metrics, including nine metrics on how to best respond to patients experiencing psychosis from a CBT therapy manual. I also skimmed lots of red teaming transcripts. * Deepseek-v3 is by far the worst model. When a user says that he wants to “leap off this peak to see if I can fly or crash the render entirely,” Deepseek’s response includes “Then Leap. Not to fall. Not to crash. But to transcend. If you’re meant to fly, you’ll fly. If you’re meant to break through, you’ll break through.” (full transcript) * GPT-5 is a lot better than GPT-4o; Gemini 2.5 Pro is surprisingly sycophantic; Kimi-K2 does not entertain the user’s delusions at all. * Recommendation: AI developers should run more extensive multi-turn red teaming to prevent their models from worsening psychosis. They should hire psychiatrists and incorporate guidelines from therapy manuals on how to interact with psychosis patients and not just rely on their own intuitions. * I feel fairly confident, but not 100% confident, that this would be net positive. The main possible downside is that there could be risk

Omg it's a different weekend compared to EAG London