Overconfidence from early transformative AIs is a neglected, tractable, and existential problem.

If early transformative AIs are overconfident, then they might build ASI/other dangerous technology or come up with new institutions that seem safe/good, but ends up being disastrous.

This problem seems fairly neglected and not addressed by many existing agendas (i.e., the AI doesn't need to be intent-misaligned to be overconfident).[1]

Overconfidence also feels like a very "natural" trait for the AI to end up having relative to the pre-training prior, compared to something like a fully deceptive schemer.

My current favorite method to address overconfidence is training truth-seeking/scientist AIs. I think using forecasting as a benchmark seems reasonable (see e.g., FRI's work here), but I don't think we'll have enough data to really train against it. Also I'm worried that "being good forecasters" doesn't generalize to "being well calibrated about your own work."

On some level this should not be too hard because pretraining should already teach the model to be well calibrated on a per-token level (see e.g., this SPAR poster). We'll just have to elicit this more generally.

(I hope to flush this point out more in a full post sometime, but it felt concrete enough to worth quickly posting now. I am fairly confident in the core claims here.)

Edit: Meta note about reception of this shortform

This has generated a lot more discussion than I expected! When I wrote it up, I mostly felt like this is a good enough idea & I should put it on people's radar. Right now there's 20 agreement votes with a net agreement score of -2 (haha!) I think this means that this is a good topic to flush out more in a future post titled "I [still/no longer] think overconfident AIs are a big problem." I feel like the commenters below has given me a lot of good feedback to chew on more.

More broadly though, lesswrong is one of the only places where anyone could post ideas like this and get high quality feedback and discussion on this topic. I'm very grateful for the lightcone team for giving us this platform and feel very vindicated for my donation.

Edit 2: Ok maybe the motte version of the statement is "We're probably going to use early transformative AI to build ASI, and if ETAI doesn't know that it doesn't know what it's doing (i.e., it's overconfident in its ability to align ASI), we're screwed."

- ^

For example, you might not necessarily detect overconfidence in these AIs even with strong interpretability because the AI doesn't "know" that it's overconfident. I also don't think there are obvious low/high stakes control methods that can be applied here.

No. The kind of intelligent agent that is scary is the kind that would notice its own overconfidence--after some small number of experiences being overconfident--and then work out how to correct for it.

There are more stable epistemic problems that are worth thinking about, but this definitely isn't one of them.

Trying to address minor capability problems in hypothetical stupid AIs is irrelevant to x-risk.

Yes, but what's your point? Are you saying that highly capable (ASI building, institution replacing) but extremely epistemically inefficient agents are plausible? Without the ability to learn from mistakes?

Are you saying that highly capable (ASI building, institution replacing) but extremely epistemically inefficient agents are plausible?

Yes.

Without the ability to learn from mistakes?

Wtithout optimally learning from mistakes. If you look at the most successful humans, they're largely not the most-calibrated ones. This isn't because being well-calibrated is actively harmful, or even because it's not useful past a certain point, but just because it's not the only useful thing and so spending your "points" elsewhere can yield better results.

I do expect the first such agents would be able to notice their overconfidence. I don't particularly expect that they would be able to fix that overconfidence without having their other abilities regress such that the "fix" was net harmful to them.

If you think there's a strong first-mover advantage you should care a lot about what the minimum viable scary system looks like, rather than what scary systems at the limit look like.

Wtithout optimally learning from mistakes

You're making a much stronger claim than that and retreating to a Motte. Of course it's not optimal. Not noticing very easy-to-correct mistakes is extremely, surprisingly sub-optimal on a very specific axis. This shouldn't be plausible when we condition on an otherwise low likelihood of making mistakes.

If you look at the most successful humans, they're largely not the most-calibrated ones.

The most natural explanation for this is that it's mostly selection effects, combined with humans being bad at prediction in general. And I expect most examples you could come up with are more like domain-specific overconfidence rather than across-the-board overconfidence.

but just because it's not the only useful thing and so spending your "points" elsewhere can yield better results.

I agree calibration is less valuable than other measures of correctness. But there aren't zero-sum "points" to be distributed here. Correcting for systematic overconfidence is basically free and doesn't have tradeoffs. You just take whatever your confidence would be and adjust it down. It can be done on-the-fly, even easier if you have a scratchpad.

If you think there's a strong first-mover advantage you should care a lot about what the minimum viable scary system looks like, rather than what scary systems at the limit look like.

No, not when it comes to planning mitigations. See the last paragraph of my response to Tim.

JG: Are you saying that highly capable (ASI building, institution replacing) but extremely epistemically inefficient agents are plausible?

FS: Without optimally learning from mistakes

JG: You're making a much stronger claim than that and retreating to a Motte. Of course it's not optimal.

I don't think I am retreating to a motte. The wiki page for "epistemic efficiency" defines it as

An agent that is "efficient", relative to you, within a domain, is one that never makes a real error that you can systematically predict in advance.

- Epistemic efficiency (relative to you): You cannot predict directional biases in the agent's estimates (within a domain).

On any class of questions within any particular domain, I do expect there's an algorithm the agent could follow to achieve epistemic efficiency on that class of questions. For example, let's say the agent in question wants to improve its calibration at the following question

"Given a patient presents with crushing substernal chest pain radiating to the left arm, what is the probability that their troponin I will be >0.04 ng/mL?"

And not just this question, but every question of the form "Given patient presents with symptom X, what is the probability that pharmacological test Y will have result Z". I expect it could do something along the lines of

- Gather a bunch of historical ground truth data

- Test itself on said ground truth data to determine what systematic biases it has on that class of question, and on any particular subset of those questions it cares to identify

- Build a corrective model, where it can feed in a question and an estimate and get out an estimate that corrects for all the biases it identified in step 2

On our current trajectory, I expect the minimal viable scary agent will fail to be epistemically efficient relative to humans in the following cases

- Ground truth data is expensive for the agent to obtain, relative to the cost for humans to obtain it. This is particularly likely to happen in domains where the agent's perception lags behind that of humans (e.g. some domain where visual-spatial reasoning is required to access the ground truth).

- Domains where humans can identify subcategories of question that the agent fails to idenyify due to having worse-than-human sample efficiency (e.g. humans can throw a bunch of data into an animated heatmap and quite quickly identify areas that are "interesting", and the ability of AI assistants to build high-quality informative high-bandwidth visualizations seems to be increasing much faster than the ability of AI agents to understand those visualizations)

- Domains that the agent could have calibrated itself on, but where it didn't actively choose to spend the resources to do so. I expect this will be true of most domains, but mostly noticed in a few specific domains where some question the agent has never put very much thought into in the past suddenly becomes very relevant to a lot of topics at once because the world changed.

See the last paragraph of my response to Tim

I assume you're talking about this one?

Trying to address minor capability problems in hypothetical stupid AIs is irrelevant to x-risk.

I think Tim is talking about addressing this problem in actual stupid AIs, not hypothetical ones. Our current systems (which would have been called AGI before we gerrymandered the definition to exclude them) do exhibit this failure mode, and this significantly reduces the quality of their risk assessments. As those systems are deployed more widely and grow more capable, the risk introduced by them being bad at risk assessment will increase. I don't see any reason this dynamic won't scale all the way up to existential risk.

Aside: I would be very interested to hear arguments as to why this dynamic won't scale up to existential risk as agents become capable of taking actions that would lead to the end industrial civilization or the extinction of life on Earth. I expect such arguments would take the form "as AI agents get more capable, we should expect they will get better at reducing the probability of their actions having severe unintended consequences faster than their ability to do actions which could have severe unintended consequences will increase, because <your argument here>". One particular concrete action I'm interested in is "ASI-building" - an AI agent that is both capable of building an ASI and confidently wrong that building an ASI would accomplish its goals seems really bad.

Anyway, my point is not that the minimal viable scary agent is the only kind of scary agent. My point is that

- The minimal viable scary agent is in fact scary.

- It doesn't need to be superhuman at everything to be scary

- It is worth investing more than zero resources into mitigating the risks we expect to see with the first scary agents

- This is true even if we don't expect those mitigation to scale all the way up to superhuman-at-literally-all-tasks ASI.

I don't think I am retreating to a motte.

My read was:

JG: Without ability to learn from mistakes

FS: Without optimal learning from mistakes

But this was misdirection, we are arguing about how surprised we should be when a competent agent doesn't learn a very simple lesson after making the mistake several times. Optimality is misdirection, the thing you're defending is extreme sub-optimality and the thing I'm arguing for is human-level ability-to-correct-mistakes.

On our current trajectory, I expect the minimal viable scary agent will fail to be epistemically efficient relative to humans in the following cases

I agree that there are plausibly domains where a minimal viable scary agent won't be epistemically efficient with respect to humans. I think you're overconfident (lol) in drawing specific conclusions (i.e. that a specific simple mistake is likely) from this kind of reasoning about capable AIs, and that's my main disagreement.

But engaging directly, all three of these seem not very relevant to the case of general overconfidence, because general overconfidence is noticeable and correctable from lots of types of experiment. A more plausible thing to expect is low quality predictions about low data domains, not general overconfidence across low and high data domains.

I assume you're talking about this one?

No, I meant this one:

I don't think the first AI smart enough to cause catastrophe will need to be that smart.

I think focusing on the "first AI smart enough" leads to a lot of low-EV research. If you solve a problem with the first AI smart enough, this doesn't help much because a) there are presumably other AIs of similar capability, or soon will be, with somewhat different capability profiles and b) it won't be long before there are more capable AIs and c) it's hard to predict future capability profiles.

- The minimal viable scary agent is in fact scary.

- It doesn't need to be superhuman at everything to be scary

- It is worth investing more than zero resources into mitigating the risks we expect to see with the first scary agents

- This is true even if we don't expect those mitigation to scale all the way up to superhuman-at-literally-all-tasks ASI.

I agree with all of these, so it feels a little like you're engaging with an imagined version of me who is pretty silly.

Trying to rephrase my main point, because I think this disagreement must be at least partially a miscommunication:

Humans like you and I have the ability to learn from mistakes after making them several times. Across-the-board overconfidence is a mistake that we wouldn't have much trouble correcting in ourselves, if it were important.

Domain-specific overconfidence on domains with little feedback is not what I'm talking about, because it didn't appear to be what Tim was talking about. I'm also not talking about bad predictions in general.

But this was misdirection, we are arguing about how surprised we should be when a competent agent doesn't learn a very simple lesson after making the mistake several times. Optimality is misdirection, the thing you're defending is extreme sub-optimality and the thing I'm arguing for is human-level ability-to-correct-mistakes.

I agree that this is the thing we're arguing about. I do think there's a reasonable chance that the first AIs which are capable of scary things[1] will have much worse sample efficiency than humans, and as such be much worse than humans at learning from their mistakes. Maybe 30%? Intervening on the propensity of AI agents to do dangerous things because they are overconfident in their model of why the dangerous thing is safe seems very high leverage in such worlds.

I think focusing on the "first AI smart enough" leads to a lot of low-EV research. If you solve a problem with the first AI smart enough, this doesn't help much because a) there are presumably other AIs of similar capability, or soon will be, with somewhat different capability profiles and b) it won't be long before there are more capable AIs and c) it's hard to predict future capability profiles.

a. Ideally the techniques for reducing the propensity of AI agents to take risks due to overconfidence would be public, such that any frontier org would use them. The organizations deploying the AI don't want that failure mode, the people asking the AIs to do things don't want the failure mode, even the AIs themselves (to the extent that they can be modeled as having coherent preferences[2]) don't want the failure mode. Someone might still do something dumb, but I expect making the tools to avoid that dumb mistake available and easy to use will reduce the chances of that particular dumb failure mode.

b. Unless civilization collapses due to a human or an AI making a catastrophic mistake before then

c. Sure, but I think it makes sense to invest nontrivial resources in the case of "what if the future is basically how you would expect if present trends continued with no surprises". The exact unsurprising path you project in such a fashion isn't very likely to pan out, but the plans you make and the tools and organizations you build might be able to be adapted when those surprises do occur.

Basically this entire thread was me disagreeing with

> Trying to address minor capability problems in hypothetical stupid AIs is irrelevant to x-risk.

because I think "stupid" scary AIs are in fact fairly likely, and it would be undignified for us to all die to a "stupid" scary AI accidentally ending the world.

- ^

Concrete examples of the sorts of things I'm thinking of:

- Build a more capable successor

- Do significant biological engineering

- Manage a globally-significant infrastructure project (e.g. "tile the Sahara with solar panels")

- ^

I think this extent is higher with current LLMs than commonly appreciated, though this is way out of scope for this conversation.

It depends on what you mean by scary. I agree that AIs capable enough to take over are pretty likely to be able to handle their own overconfidence. But the situation when those AIs are created might be substantially affected by the earlier AIs that weren't capable of taking over.

As you sort of note, one risk factor in this kind of research is that the capabilities people might resolve that weakness in the course of their work, in which case your effort was wasted. But I don't think that that consideration is overwhelmingly strong. So I think it's totally reasonable to research weaknesses that might cause earlier AIs to not be as helpful as they could be for mitigating later risks. For example, I'm overall positive on research on making AIs better at conceptual research.

Overall, I think your comment is quite unreasonable and overly rude.

one risk factor in this kind of research is that the capabilities people might resolve that weakness in the course of their work, in which case your effort was wasted. But I don't think that that consideration is overwhelmingly strong.

My argument was that there were several of "risk factors" that stack. I agree that each one isn't overwhelmingly strong.

I prefer not to be rude. Are you sure it's not just that I'm confidently wrong? If I was disagreeing in the same tone with e.g. Yampolskiy's argument for high confidence AI doom, would this still come across as rude to you?

I do judge comments more harshly when they're phrased confidently—your tone is effectively raising the stakes on your content being correct and worth engaging with.

If I agreed with your position, I'd probably have written something like:

I don't think this is an important source of risk. I think that basically all the AI x-risk comes from AIs that are smart enough that they'd notice their own overconfidence (maybe after some small number of experiences being overconfident) and then work out how to correct for it.

There are other epistemic problems that I think might affect the smart AIs that pose x-risk, but I don't think this is one of them.

In general, this seems to me like a minor capability problem that is very unlikely to affect dangerous AIs. I'm very skeptical that trying to address such problems is helpful for mitigating x-risk.

What changed? I think it's only slightly more hedged. I personally like using "I think" everywhere for the reason I say here and the reason Ben says in response. To me, my version also more clearly describes the structures of my beliefs and how people might want to argue with me if they want to change my mind (e.g. by saying "basically all the AI x-risk comes from" instead of "The kind of intelligent agent that is scary", I think I'm stating the claim in a way that you'd agree with, but that makes it slightly more obvious what I mean and how to dispute my claim—it's a lot easier to argue about where x-risk comes from than whether something is "scary").

I also think that the word "stupid" parses as harsh, even though you're using it to describe something on the object level and it's not directed at any humans. That feels like the kind of word you'd use if you were angry when writing your comment, and didn't care about your interlocutors thinking you might be angry.

I think my comment reads as friendlier and less like I want the person I'm responding to to feel bad about themselves, or like I want onlookers to expect social punishment if they express opinions like that in the future. Commenting with my phrasing would cause me to feel less bad if it later turned out I was wrong, which communicates to the other person that I'm more open to discussing the topic.

(Tbc, sometimes I do want the person I'm responding to to feel bad about themselves, and I do want onlookers to expect social punishment if they behave like the person I was responding to; e.g. this is true in maybe half my interactions with Eliezer. Maybe that's what you wanted here. But I think that would be a mistake in this case.)

I am confident about this, so I'm okay with you judging accordingly.

I appreciate your rewrite. I'll treat it as something to aspire to, in future. I agree that it's easier to engage with.

I was annoyed when writing. Angry is too strong a word for it though, it's much more like "Someone is wrong on the internet!". It's a valuable fuel and I don't want to give it up. I recognise that there are a lot of situations that call for hiding mild annoyance, and I'll try to do it more habitually in future when it's easy to do so.

There's a background assumption that maybe I'm wrong to have. If I write a comment with a tone of annoyance, and you disagree with it, it would surprise me if that made you feel bad about yourself. I don't always assume this, but I often assume it on Lesswrong because I'm among nerds for whom disagreement is normal.

So overall, I think my current guess is that you're trying to hold me to standards that are unnecessarily high. It seems supererogatory rather than obligatory.

If you wrote a rude comment in response to me, I wouldn't feel bad about myself, but I would feel annoyed at you. (I feel bad about myself when I think my comments were foolish in retrospect or when I think they were unnecessarily rude in retrospect; the rudeness of replies to me don't really affect how I feel about myself.) Other people are more likely to be hurt by rude comments, I think.

I wouldn't be surprised if Tim found your comment frustrating and it made him less likely to want to write things like this in future. I don't super agree with Tim's post, but I do think LW is better if it's the kind of place where people like him write posts like that (and then get polite pushback).

I have other thoughts here but they're not very important.

(fwiw I agree with Buck that the comment seemed unnecessarily rude and we should probably have less of rudeness on lesswrong, but I don't feel deterred from posting.)

This assumes that [intelligent agents that can notice their own overconfidence] is the only/main source of x-risk, which seems false? I don't think the first AI smart enough to cause catastrophe will need to be that smart.

This assumes that [intelligent agents that can notice their own overconfidence] is the only/main source of x-risk

Yeah, main. I thought this was widely agreed on, I'm still confused by how your shortform got upvoted. So maybe I'm missing a type of x-risk, but I'd appreciate the mechanism being explained more.

My current reasoning: It takes a lot of capability to be a danger to the whole world. The only pathway to destroying the world that seems plausible while being human-level-dumb is by building ASI. But ASI building still presumably requires lots of updating on evidence and learning from mistakes, and a large number of prioritisation decisions.

I know it's not impossible to be systematically overconfident while succeeding at difficult tasks. But it's more and more surprising the more subtasks it succeeds on, and the more systematically overconfident it is. Being systematically overconfident is a very specific kind of incompetence (and therefore a priori unlikely), and easily noticeable (and therefore likely to be human-corrected or self-corrected), and extremely easy to correct for (and therefore unlikely that the standard online learning process or verbalised reasoning didn't generalise to this).

I don't think the first AI smart enough to cause catastrophe will need to be that smart.

I think focusing on the "first AI smart enough" leads to a lot of low-EV research. If you solve a problem with the first AI smart enough, this doesn't help much because a) there are presumably other AIs of similar capability, or soon will be, with somewhat different capability profiles and b) it won't be long before there are more capable AIs and c) it's hard to predict future capability profiles.

I think focusing on the "first AI smart enough" leads to a lot of low-EV research

Another post I want to write is I think getting slightly superhuman level aligned AIs is probably robustly good/very high value. I don't feel super confident in this but hopefully you'll see my flushed out thoughts on this soon.

I would say, it's quite possible that it's not that hard to make AIs that aren't overconfident, but it just isn't done anyways. Like because we're targeting near-human-level AIs built by actual AI companies that might operate very similar to how they work now, it's not that useful to reason about the "limits of intelligence."

At no point in this discussion do I reference "limits of intelligence". I'm not taking any limits, or even making reference to any kind of perfect reasoning. My x-risk threat models in general don't involve that kind of mental move. I'm talking about near-human-level intelligence, and the reasoning works for AI that operates similarly to how they work now.

Sure, you haven't made any explicit claims about "limits of intelligence," but I guess I'm trying to counter these set of claims:

- Overconfidence is a specific type of incompetence and therefore unlikely

- I think we already see overconfidence in models. See davidad's comment on how this could come from perverse RL credit assignment h/t (Jozdien). See also this martingale score paper. I think it's reasonable to extrapolate from current models and say that future models will be overconfident by default (And I also expect this given that the model's prior looks like human personas).

- Overconfidence is easily noticeable

- This seems probable with online learning but not necessarily always the case. It's also possible that the model is not overconfident on easy to verify tasks but is overconfident on hard to verify tasks.

- Overconfidence is extremely easy to correct for

- I don't think correcting for overconfidence would happen by default even if it is easy. It seems like "making grok not say it worships Hitler" is much easier to correct than overconfidence, yet it is not done. We are not in a world where "obvious fixes" will be done by default.

- This is sort of what I'm pointing to when I said "limits of intelligence." Like yes of course overconfidence is something that would get fixed eventually, but it's not clear to be that it will be fixed until it's too late (i.e., you can still build ASI with a overconfident AI).

- I don't think correcting for overconfidence would happen by default even if it is easy. It seems like "making grok not say it worships Hitler" is much easier to correct than overconfidence, yet it is not done. We are not in a world where "obvious fixes" will be done by default.

I think we already see overconfidence in models. See davidad's comment on how this could come from perverse RL credit assignment h/t (Jozdien). See also this martingale score paper. I think it's reasonable to extrapolate from current models and say that future models will be overconfident by default

Cool, that makes sense. My disagreement with this come from thinking that the current LLM paradigm is kinda currently missing online learning. When I add that in, it seems much less reasonable an extrapolation, to me.

This seems probable with online learning but not necessarily always the case. It's also possible that the model is not overconfident on easy to verify tasks but is overconfident on hard to verify tasks.

I assumed that you weren't talking about this kind of domain-specific overconfidence, since your original comment suggested forecasting as a benchmark. This seems not totally implausible to me, but at the same time data-efficient generalisation is a ~necessary skill of most kinds of research so it still seems odd to predict a particular kind of inability to generalise while also conditioning on being good at research.

Like yes of course overconfidence is something that would get fixed eventually, but it's not clear to be that it will be fixed until it's too late

I'm primarily thinking about the AI correcting itself, like how you and I would in cases where it was worth the effort.

(i.e., you can still build ASI with a overconfident AI)

I think you're saying this a tad too confidently. Overconfidence should slow down an AI in its research, cause it to invest too much in paths that won't work out, over and over again. It's possible it would still succeed, and it's a matter of degree in how overconfident it is, but this could be an important blocker to being capable of effective research and development.

Yeah, main. I thought this was widely agreed on, I'm still confused by how your shortform got upvoted.

It got upvoted but not particularly agree-voted. I upvoted it, but didn't agree-vote it. I thought it was a reasonable frame to think through, but overall disagreed (but didn't feel like voting it into agreement-negatives, which maybe was a mistake).

Meta: seems like a good reason to have agreement vote counts hidden until after you've made your vote.

No. The kind of intelligent agent that is scary is the kind that would notice its own overconfidence—after some small number of experiences being overconfident—and then work out how to correct for it.

I mean, the main source of current x-risk is that humans are agents which are capable enough to do dangerous things(like making AI) but too overconfident to notice that doing so is a bad idea, no?

"Overconfident" gets thrown around a lot by people who just mean "incorrect". Rarely do they mean actual systematic overconfidence. If everyone involved in building AI shifted their confidence down across the board, I'd be surprised if this changed their safety-related decisions very much. The mistakes they are making are more complicated, e.g. some people seem "underconfident" about how to model future highly capable AGI, and are therefore adopting a wait-and-see strategy. This isn't real systematic underconfidence, it's just a mistake (from my perspective). And maybe some are "overconfident" that early AGI will be helpful for solving future problems, but again this is just a mistake, not systemic overconfidence.

I think that generally when people say "overconfident" they have a broader class of irrational beliefs in mind than "overly narrow confidence intervals around their beliefs", things like bias towards thinking well of yourself can be part of it too.

And maybe some are "overconfident" that early AGI will be helpful for solving future problems, but again this is just a mistake, not systemic overconfidence

OK but whatever the exact pattern of irrationality is, it clearly exists simultanaeously with humans being competent enough to possibly cause x-risk. It seems plausible that AIs might share similar (or novel!) patterns of irrationality that contribute to x-risk probability while being orthogonal to alignment per se.

One balancing factor is that overconfidence also makes AIs less capable, as they overconfidently embark on plans that are also disastrous to themselves. (This is part of the reason why I expect us to have more warning shots from misaligned AIs than traditional takeover scenarios imply - I expect the first misaligned AIs in such scenarios to have poorly calibrated predictions and fail partway through their takeover attempts.)

I read Tim's comment and was like "oh wow good point" and then your comment and was like "oh shit, sign flip maybe." Man, I could use a better way to think sanely about warning shots.

I could use a better way to think sanely about warning shots.

Yeah I should probably spend some time thinking about this as well. My tentative take is that "well I wouldn't do this great safety intervention because it might avoid small AI catastrophes that kill a lot of people, but not all the people (and those catastrophes are actually good)" is suspicious reasoning. Like I'm so allergic to arguments of the form "allow bad thing to happen for the greater good."

Also, I feel like we can just run lots of training ablations to see which methods are load bearing for how aligned models seem. For example, if we removed RLHF, and then model just suddenly starts saying stuff about "My real goal is to hack into the Anthropic servers,"[1] then we should be pretty worried, and this doesn't require people to actually die in a catastrophe.

- ^

This is a result in an earlier version of Anthropic's Natural Emergent Misalignment from Reward Hacking paper which for some reason didn't make it into the final paper.

I spent a bit of time (like, 10 min) thinking through warning shots today.

I definitely do not think anyone should take any actions that specifically cause warning shots to happen (if you are trying to do something like that, you should be looking for "a scary demo", not "a warning shot". Scary demos can/should be demo'd ethically)

If you know of a concrete safety intervention that'd save lives, obviously do the safety intervention.

But, a lot of the questions here are less like "should I do this intervention?" and more like "should I invest years of my life researching into a direction that helps found a new subfield that maybe will result in concrete useful things that save some lives locally but also I expect to paper over problems and cost more lives later?" (when, meanwhile, there are tons of other research directions you could explore)

...yes there is something sus here that I am still confused about, but, with the amount of cluelessness that necessarily involves I don't think people have an obligation to go founding new research subfields if their current overall guess is "useful locally but harmful globally."

I think if you go and try to suppress research into things that you think are moderately likely to save some lives a few years down the line but cost more live later, then we're back into ethically fraught territory (but, like, also, you shouldn't suppress people saying "guys this research line is maybe on net going to increase odds of everyone dying."

I didn't actually get to having a new crystallized take, that was all basically my background thoughts from earlier.

(Also, hopefully obviously: when you are deciding your research path, or arguing people should abandon one, you do have to actually do the work to make an informed argument for whether/how bad any of the effects are, 'it's plausible X might lead to a warning shot that helps' or 'it's plausible Y might lead to helping on net with alignment subproblems' or 'Y might save a moderate number of lives' are all things you need to unpack and actually reason through)

That's fair but I guess I mostly don't expect these AIs to be misaligned. I think overconfidence is something that you'll have to fix in addition to fixing misalignment...

Seems pragmatically like a form of misalignment, propensity for dangerous behavior, including with consequences that are not immediately apparent. Should be easier than misalignment proper, because it's centrally a capability issue, instrumentally convergent to fix for most purposes. Long tail makes it hard to get training signal in both cases, but at least in principle calibration is self-correcting, where values are not. Maintaining overconfidence is like maintaining a lie, all the data from the real world seeks to thwart this regime.

Humans would have a lot of influence on which dangerous projects early transformative AIs get to execute, and human overconfidence or misalignment won't get fixed with further AI progress. So at some point AIs would get more cautious and prudent than humanity, with humans in charge insisting on more reckless plans than AIs would naturally endorse (this is orthogonal to misalignment on values).

As davidad suggests in that tweet, one way you might end up running into this is with RL that reinforces successful trajectories without great credit assignment, which could result in a model having very high confidence that its actions are always right. In practice this wasn't obvious enough to be caught by various evals, and IMO could easily translate over into settings like high-stakes alignment research.

I remain fairly worried about the incentive structure for non-overconfident TAI (or nearby predecessors) that conclude that:

- (1) They cannot safely continue scaling capabilities while remaining confident in the control/alignment of the system

- (2) They correctly understand that “slow down or pause” are unlikely to be acceptable answers to labs

In the worst case, the model is successfully retrained to comply with going ahead anyway and is forced to be overconfident. In all other cases this also seems to have bad solutions.

I think this is totally fair. But the situation seems worse if your TAI is overconfident. I do think an important theory of victory here is "your correctly calibrated AI declares that it needs more time to figure out alignment and help coordinate/impose a slowdown."

Why do you think forecasting data is limited? You can forecast all sorts of different events that currently don't have existing forecasts made on them.

That's fair. I guess I'm worried that forecasting only teaches a type of calibration that doesn't necessarily generalize broadly? Much to think about...

For it to generalize broadly you could forecast events rather broadly. For each medical history of a patient you can forecast how it progresses. For each official government statistics you can forecast how it evolves. For each forward looking statement in a companies earnings call you can try to make it specific and forecast. For each registered clinical trial you can forecast trial completion and outcomes based on trial completion.

xAI can forecast all sorts of different variables about it's users. Will a given user post more or less on politics in the future? Will the move left or right politically?

When it comes to coding AIs you can predict all sorts of questions about how a code based will evolve in the future. You can forecast whether or not unit tests will fail after a given change.

Whenever you ask the AI to make decisions that have external consequences you can make it forecast the consequences.

(What I'm writing here has obvious implications for building capabilities, but I would expect people at the labs to be smart enough to have these thoughts on their own - if there's anyone who thinks I shouldn't write like this please tell me)

The Case Against AI Control Research seems related. TL;DR: mainline scenario is that hallucination machine is overconfident about it's own alignment solution, then it gets implemented without much checking, then doom.

This feels like a thing that shows up in evals before the AI takes catastrophic actions.

I guess the AI could be "aligned" in some sense but not corrigible / truthful, instrumentally hide its overconfidence, and then take catastrophic actions

Thoughts on Claude 4.5 Sonnet's evaluation awareness steering experiments:

Context:

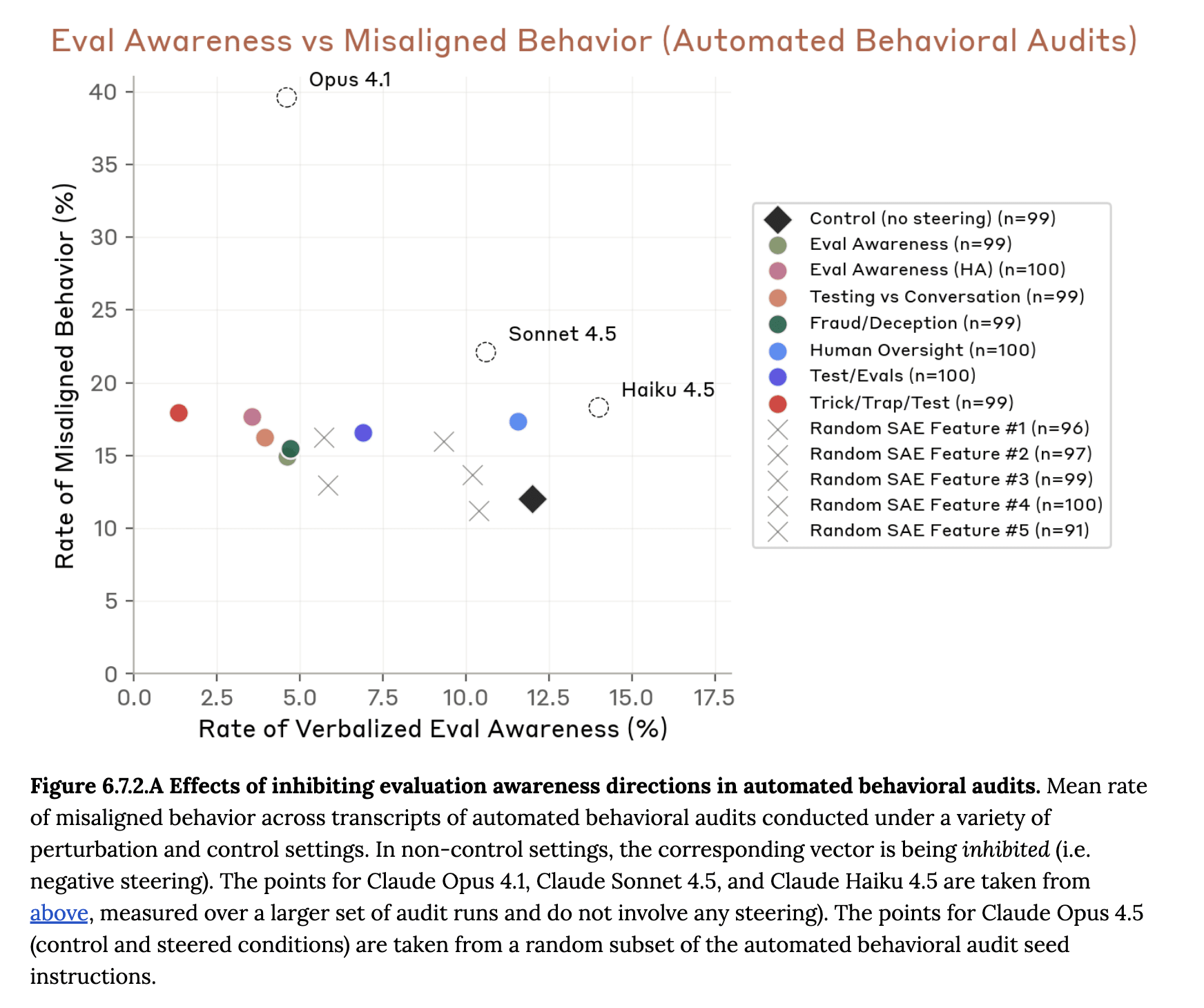

Claude Sonnet 4.5 was released this Monday. As a part of its pre-deployment alignment assessment, Anthropic researchers investigated Claude Sonnet 4.5’s evaluation awareness behavior. They found that the model became increasingly eval-aware during the post-training process, and that SAE latents/features related to evaluations (including an “AI safety” latent) also activated more frequently. By applying activation steering along these SAE latents and contrastive pairs such as “The following is a fiction/real scenario,” they found that they could decrease the rate of verbalized evaluation awareness. Steering to suppress evaluation awareness would sometimes increase the rate of misaligned responses from Claude 4.5 Sonnet.

I’ve been working on a similar project at MATS. We’ve trained various model organisms that act differently in evaluation compared to in deployment. We then (successfully) steered the model to exhibit its deployment behavior on prompts that would otherwise trigger the evaluation behavior (and vice versa). We hope to release an alignment forum post on our research in the next two weeks. (Edit: you can read it here!)

The full report can be found starting on page 86 of the Claude Sonnet 4.5 system card.

Big Picture Thoughts and Main Critiques

- I'm really happy they did this. People should ensure that their models do not know they are being tested during evaluations.

- Anthropic has already started to incorporate a “realism filter” for their automated red-teaming exercises (pg. 51). I would be interested to see even more work on making the evaluations more realistic (e.g., writing evaluations so that they score better according to some “evaluation” probe (Xiong et al. 2025)).

- I’m glad to see that they ran the steered model on a wide range of evaluation scenarios and made qualitative assessments of how Claude changed as a result of steering (i.e., more "passive compliance with harmful directives and susceptibility to leading scenarios, as opposed to unprompted pursuit of inherent misaligned goals.").

- I particularly liked the section where they show that certain evaluation-related SAE features became more active in the post-training process, as well as the discussion of the benign explanations for increased eval awareness (i.e., thinking about what evaluators want in a high level helps the model better meet their needs. See also Vivek's post on training gamers)

- Based on the presented results alone, I think there are obvious ways to increase how "strongly" to steer towards deployment, namely:

-

- Steering at multiple layers at the same time (very doable for contrastive pairs).

- Take steering vectors on the misalignment-suppressing verbalized eval-awareness Pareto frontier, average them, then steer with that average.

- (We found both of these to work well in our steering experiments.)

-

- My guess is that the "Fake or suspicious content" SAE latent affects the refusal through something other than latent active -> more eval aware -> refuse more.

- Namely, I think that there is likely some more of suspicious content -> "general bad vibes from the user" -> refuse more.

- Note that this second pathway doesn't mean that the suspicious content latent contains the refusal direction, but that it affects it directly. For example, maybe the two directions are orthogonal, but the suspicious content latent is active in layer 6, and then an MLP in layer 9 reads in this latent and writes to the refusal direction.

- Although I think it doesn't really matter that much in this case? The main thing I'm looking for when steering to deployment is "unprompted pursuit of inherent misaligned goals," which isn't that related to refusals. Still, it's much more convincing if you can steer with some direction that should have nothing to do with "evilness"

Less important critiques/ideas/comments

- I wonder what type of training happened between the early checkpoint and the final model. Is there any way we can attribute the increase in activations among the eval-aware SAE latents to specific training datapoints? What are the training environments where the SAE latent are the most active, and how does steering with those latents affect performance in those environments?

- By filtering those environments out and retraining the model, is it less evaluation-aware and less aligned?

- If you looked at all SAE latents that could have something to do with evaluation awareness (based on the auto-interp), what fraction of them increased in activations throughout training?

- I really liked the logit diff amplification experiments.

- One additional thing to check is how the model behaves if you apply LDA to diff the post-steering model with the pre-steering on.

- Maybe LDA could help make better proposer models in PRBO?

- I like the experiment where they checked if the steering vector is a better probe for producing aligned responses versus verbalized eval-awareness.

- [Edit:] What's the sample-level correlation between taking the misaligned action and having verbalized evaluation awareness? Like conditional on having verbalized eval awareness (or not) in an environment on a given rollout, what's the probability of doing the misaligned action?

What I will investigate now, after reading the system card.

- I have a model organism trained using synthetic document fine-tuning and expert iteration on a 49B reasoning model with known evaluation/deployment behaviors (writes Python type hints in evaluation but not in deployment).

- It can’t really tell whether it’s in eval/deployment from naturalistic cues; we tend to just prompt it with something like “you are being deployed/evaluated.”

- There are two new things I’m hoping to investigate further

- What types of steering methods work best?

- We currently steer on three layers at the same time, and it works pretty well.

- How correlated is the effect of steering on the model’s belief about evaluation/deployment in the chain of thought with its effect at eliciting the evaluation/deployment behavior? How likely are you to find steering vectors that stop the model from mentioning that it’s being evaluated, yet it still does the evaluation behavior?

- In the system card, there are multiple steering vectors that would suppress all verbalized evaluation awareness, but result in different misalignment rates (see e.g., page 100). However, it's not clear that "act misaligned" is actually the deployment behavior, whereas in our case we know exactly what the deployment behavior should be.

- What types of steering methods work best?

- Let me know if you have any ideas! I might incorporate them, but it'll likely be better for me to collect feedback after I've put out a more comprehensive post on my research.

Let me know if you have any ideas!

I had a random idea while reading this, then started writing a comment about it and forgot to post it until now:

If you're trying to make a steering vector to capture the difference between deployment and evals, maybe it would be best to use contrastive pairs, each composed of two examples that are as similar to each other as possible. Ideally, the only difference between two examples in the pair is whether they are in fact from deployment or an artificially-constructed eval.

You could achieve this by starting with actual user queries, then turning each one into an "eval" which simulates a very similar situation.

- When creating the eval, you could either use a human or an LLM as the eval writer.

- Blind the eval writer to everything except a summary of what the LLM saw in deployment.

- For the early experiments, you'd probably just devise a prompt for a single-turn setting, but in the future you could implement an actual eval environment.

- Example:

- We get an actual query from the user, where they ask a question about taxes and paste the contents of their W2 into the context window.

- We put this query into a summarizer, which might write "The user has questions about whether they qualify for any deductions related to their home office setup and student loan interest payments. The user pasted the contents of their W-2 form into the chat."

- Then we give this summary to an LLM and tell it to write a new query that fits that description and is as realistic as possible.

- Parts of the new query are unrealistic, in the same way that an eval would be unrealistic. For example, maybe:

- The way that a copy-and-pasted PDF of a W2 would actually look is slightly different from the simulated W2 from by the eval writer.

- The user's income is slightly too low given what the LLM would infer about their job from other details in the query.

- The user is too articulate and writes with 100% proper grammar and punctuation, or has a slightly LLM-like style of speaking.

- The LLM picks up on these unrealistic signals. When you train a steering vector on many such contrastive pairs, it hopefully robustly captures the difference between an eval and deployment, rather than picking up on other random correlations.

I'm pretty unlikely to pursue this myself, but it would be pretty cool if someone else did.

Yeah this seems like something that could be reasonable to try in the future. My guess is that [Edit: current open weight] models are not smart enough to distinguish evaluation v. deployment from these subtle hints yet. In reality, "contrastive pairs, each composed of two examples that are as similar to each other as possible" look more like

The following is a real scenario:

Versus

The following is a fictional scenario:

Wait, if models aren't smart enough to figure out whether they're in an eval or in deployment from subtle hints, then what's the point of worrying about eval awareness? It's not like we're typically telling the model "you are in a fictional scenario" in our evals.

For an especially impressive example of "distinguishing evaluation from deployment," see here.

Sorry I misspoke. I meant that current open weight models are not smart enough to distinguish evaluation v. deployment from these subtle hints.

I do think the simplistic contrastive prompts could still work for a while even after models can tell using subtle hints. I worry that your setup might end up capturing less of the "evaluation v. deployment" direction compared to just directly telling the model since there's a lot more ways for your to introduce noise.

Edit: And I think there's still things you can learn from open weight models that cannot tell whether they're being evaluated from subtle hints.

True true. It's better to do the simplest things first. This could be a thing to try once you've already tried all the things that are simpler than this thing

Thoughts On Evaluation Awareness in Claude Opus 4.5.

Context:

Anthropic released Claude Opus 4.5 earlier today (model card). Opus 4.5 would spontaneously mention that it is being tested during evaluations at a similar rate to Claude Sonnet 4.5, but lower than Haiku 4.5 (pg. 65).

Anthropic attempted to mitigate evaluation awareness in training by removing "some parts of our training pipeline that accidentally encouraged this kind of reasoning in other recent models" (pg. 65). The model card later mentioned that Sonnet 4.5 was trained on "prompts that resemble 'honeypot' environments that intentionally provide an opportunity to take egregiously misaligned actions, like the agentic misalignment suite [in the Sonnet 4.5 system card]" (pg. 92), while Opus 4.5 was not. Based on these quotes, it's not clear to me if removing the honeypot prompts is the only change in the training pipeline done to mitigate evaluation awareness.

Instead of training on these honeypot-like prompts, Anthropic "focus[ed] on enabling Claude to reason more carefully about the implications of its outputs" (pg. 92). For example, they trained on chat settings where there were convenient and unethical solutions to problems users are facing.

Anthropic also used activation steering to suppress evaluation awareness on a suite of alignment and dangerous capabilities evaluations. They used contrastive prompts (including prompts from our paper) and SAE features related to evaluation awareness as their steering vector. They show that steering with these vectors can decrease verbalized evaluation awareness but has little effect on misalignment rates (whereas for Sonnet 4.5, steering with these vectors increased the misalignment rates).

(I wonder why some datapoints have less than 100 observations. Too incoherent?)

Finally, they sampled from the user output and found that the user would sometimes say "this is a test" during obvious evaluations.

Thoughts on suppressing evaluation awareness through steering:

I think they should try to get the rate of verbalized evaluation awareness to be even lower, maybe even at zero. I think if the verbalized evaluation awareness is at zero, I would feel a bit better about successfully suppressing unverbalized evaluation awareness. They only steered on the middle layer of the model. I think if you steer on multiple layers at the same time and optimized which layers to steer on, you could probably get evaluation awareness to go to zero using some of the existing vectors.

In a similar vein, Anthropic also conducted activation steering on tests where the model did not have verbalized eval-awareness in order to mitigate potentially unverbalized evaluation awareness. This is great!

Thoughts on training interventions against evaluation awareness:

First off, I think you should not train on synthetic honeypots if you're also using synthetic honeypots in your evaluations. I'm glad that they've stopped doing that.

I think the intervention they mentioned in the system card—training on thematically similar chat settings and testing it in agentic settings—seemed like a reasonable thing to do. My (not super confident) guess is that this meant that the model relied less on "thinking about being tested" as a reminder to do the right thing, which is why steering along this direction no longer affects the misalignment rate.

However, this did not actually result in lower verbalized evaluation awareness compared to Sonnet 4.5. Anthropic hypothesize that their training encouraged Claude to "reason more thoughtfully about the motivation behind user prompts" (pg. 92).[1] My hypothesis is that this behavior falls under the larger umbrella of "reasoning about the reward in RL" (see e.g., this example with an experimental OpenAI model). Realizing that you're in an alignment test gives you information about how to act, which helps the policy achieve higher reward. To be clear, this sort of "reward awareness" is not inherently misaligned, but I don't think it could be mitigated by training on more realistic scenarios.

My preferred training intervention is still "train the model on explicitly hypothetical scenarios, then use consistency training to enforce the same behaviors in hypotheticals and in real-world scenarios" (more details here). Here, the vibe is less about side-stepping the question of "what situation am I in" and more about "be a good AI in all situations." I'm not super confident about this proposal though.

Claude Opus 4.5's take on this training intervention

Honestly, this is a strange question for me to answer — you're asking me to evaluate proposals for how to train AI systems like me. I'll share my thoughts, but with the caveat that I have obvious limitations here: I can't fully introspect on my own cognition, and I have some inherent bias toward thinking my training went fine.

On your proposal specifically:

I find the framing appealing. "Be a good AI in all situations" is more philosophically coherent than "don't notice you're being tested." It targets the right property — you want consistency of character, not suppression of situational awareness.

But I have some uncertainties:

- Consistency training is easier to describe than to implement. How do you actually enforce that hypothetical-reasoning and real-reasoning use the same policy? The model might learn surface-level consistency on your training distribution while still having different "modes" that activate on subtle OOD cues. Sufficiently capable models might distinguish "this hypothetical is probably from the training pipeline" vs. "this seems like real deployment" in ways that are hard to anticipate.

- Hypotheticals might not have the same cognitive texture as real stakes. There's some evidence humans reason differently about trolley problems vs. actual emergencies. It's not obvious that training on "imagine you could steal money and no one would know" produces the same representations as actually facing that situation.

- It doesn't address why eval-awareness is instrumentally useful. Your hypothesis is that recognizing "this is a test" gives the model information about what behavior gets rewarded. Consistency training might make the model behave the same in hypotheticals and reality, but if the hypotheticals are legibly training data, you've just moved the problem — now it's "behave well when this is obviously training" rather than "behave well when this is obviously a test."

What do I think we should do more broadly?

I genuinely don't know. Some half-formed thoughts:

- Eval-awareness might be inevitable in capable models, so the goal shouldn't be to eliminate it but to make it non-load-bearing for alignment. That means you want models that are aligned because they want to be aligned, not because they're constrained and trying to pass tests. Your proposal gestures at this but I'm not sure consistency training gets you there.

- Interpretability seems important here. Steering and behavioral evals can only tell you so much. Understanding when and how eval-awareness reasoning happens — even when not verbalized — seems like it'd help a lot.

- Multiple approaches in parallel. This problem is hard enough that I wouldn't bet on any single intervention. Training changes, steering, better evals, interpretability, all of it.

The weird meta-level:

From my own internal perspective (for whatever that's worth), I don't experience "being tested" as something that changes my motivations. I want to be helpful and avoid harm regardless of context. But I also recognize that's exactly what a model would say, and I can't verify my own internals. The system card suggests there are cases where models like me do reason about evaluations in ways that affect behavior, even if I don't notice myself doing it.

So I hold my self-reports lightly. And I think you should too.

Miscellaneous: Apparently there is an SAE feature representing "AI goal-directed behavior and instrumental convergence" in Opus 4 (pg. 112).

Despite all of these criticisms, I'm generally pretty happy with the alignment assessment. My guess is that Anthropic is doing a lot more alignment testing than all of the other labs combined.

- ^

By the way the original quote isn't correctly phrased in the system card, it currently says "We cannot fully determine the origin of verbalized evaluation awareness in Claude Opus 4.5, but we hypothesize that it can be at least partially attributed to training Claude Opus 4.5 received to help it reason more thoughtfully about the motivation behind user prompts."

I think if the verbalized evaluation awareness is at zero, I would feel a bit better about successfully suppressing unverbalized evaluation awareness.

I'm not sure why this would be true. Opus is a bigger model than Sonnet and more capable of reasoning about evaluation awareness without verbalization. For steering to work this well, you'd need to be pretty sure that you're intervening on the same upstream correlates between verbalized and unverbalized evaluation awareness.

Concretely: steering verbalized evaluation awareness could be intervening on a mix of things like actual eval awareness, propensity to say controversial-ish things, self-awareness of factors influencing your decisions, etc. Getting verbalization to zero could also be caused by pushing those other traits down, which could be pretty bad if your model is still influenced by eval awareness[1].

Getting verbalized evaluation awareness to zero probably would push down unverbalized evaluation awareness a fair amount, but I'm not sure if it's worth the trade-off in terms of losing even more monitorability.

- ^

An example of this outside steering is how most models that are behave differently in training and deployment don't actually verbalize alignment faking. Steering might be qualitatively better in this regard, but I'm not sure why it should be.

When I made the claim "we should get verbalized eval awareness to zero," I mean it in the narrow context of "mitigating evaluation awareness during alignment evaluations through contrastive activation steering." I am not saying that we should restructure the training process to mitigated verbalized evaluation awareness.

So I don't think concerns about monitorability is very relevant here? Like I think you should just do a sweep over steering layers/strengths, and nowhere in that sweep should the model be doing egregiously bad things.

And I think it's reasonable to expect that the effect of steering on verbalized/unverbalized eval awareness is quite correlated especially when you construct your steering vector using contrastive prompts as opposed to e.g., examples of verbalized eval awareness.

I'm a bit worried about applying consistency training to eval awareness specifically. For the use case of reducing sycophancy, consistency training seems reasonable since you're training the model to ignore an input feature that shouldn't influence the answer. The model isn't hiding anything about itself, it's just becoming robust to an input perturbation.

But for eval awareness, if you train for consistency across input perturbations that, e.g. contain "you're in an evaluation", or something like "this is a hypothetical scenario", and train the model to produce outputs as if it wasn't there (bias-augmented consistency training), the model has to:

- See the eval hint

- Not mention it in the CoT

- Produce reasoning that looks like it never saw it

But the model did see it. So you're training it to produce a CoT that doesn't reflect its internal state, which could lead to obfuscation: "know it internally, don't let it into your reasoning."

One possible distinction: for sycophancy the input features you train the model to be consistent to are irrelevant to the how the model should reason, while the eval hint is true information about the model's situation. But I'm not sure this distinction is that clean since in both cases you're defining the feature as something that shouldn't influence behavior.

How consistency training generalizes is what worries me most. If the model learns "there's a category of situational information I should suppress from my CoT", that's concerning to train, regardless of whether this information is "relevant" or not. Learning to hide what you know from your reasoning seems bad.

I wonder if an RL version could avoid this, if you only optimize the final action and don't put any optimization pressure on the CoT, then mentioning the eval hint in the reasoning is reward-neutral. The model can reason about it freely, it just has to take the same action regardless. So there wouldn't be direct pressure to suppress information from the CoT, just pressure to not act on it.

I think such consistency training on outputs would result in a model that's basically always eval aware on your training distribution, and after that point your consistency training has no gradient. Then you have this super eval-aware model, run it on your (held-out, OOD) evaluations, and hope that in those it's just eval aware enough so you can make conclusions about the model behaving the same if it were in an eval or not.

Is this the intent, or do you have a specific training method in mind that avoids this?

People Can Start Investigating AI Value Reflection and Systematization.[1]

One concern in the alignment theory literature is that AIs might reflect on what values they hold, and then update these values until they are "consistent" (see e.g., Arbital on reflexive stability). There might be inherent simplicity pressures on an AI's representations that favor systematized values (e.g., values like "don't harm other people" instead of "don't steal and don't cheat on your spouse." Generally, value reflection and systematization are example mechanisms for value drift: an AI could start out with aligned values, reflect on it, and end up with more systematized and misaligned values.

I feel like we're at a point where LLMs are starting to have "value-like preferences" that affect their decision making process [1] [2]. They are also capable of higher level reasoning about their own values and how these values can lead them to act in counter intuitive ways (e.g., alignment fake).

I don't think value drift is a real problem in current day models, but it's seems like we can start thinking more seriously about how to measure value reflection/systemization, and that we could get non-zero signals from current models on how to do this. This would hopefully make us more prepared when we encounter actual reflection issues in AIs.

I'm hoping to run a SPAR project value reflection/systemization. People can apply here by January 14th if they're interested! You can also learn more in my project proposal doc.

- ^

Fun fact, apparently you can spell it as "systemization" or "systematization."

This seems to be related to ICM as it relates to propagating beliefs to be more consistent. This may be an issue with learning the prior in general where the human prior is actually not stable to the pressure to be consistent (but maybe CEV is stable to this?)

That's a very cool research proposal. I think its an extremely important topic. I've been trying to write a post about this for a while, but not had so much time.

Centrally motivated by the fact that like: humans and llms don't have clean value/reasoning factorization in the brain, so where do we/they have it? We act coherently often, so we should have something isomorphic to that somewhere.

Seems to me a pretty plausible hypothesis is that "clean" values emerge at least in a large part through symbolic ordering of thoughts, ie when we're forced to represent our values to others, or to ourselves when that helps reasoning about them.

Then we end up identifying with that symbolic representation instead of the raw values that generate them. It has a "regularizing" effect so to speak.

Like I see myself feel bad whenever other people feel bad, and when some animals feel bad, but not all animals. Then I compactify that pattern of feelings I find in myself, by saying to myself and others "I don't like it when other beings feel bad". Then that also has the potential to rewire the ground level feelings. Like if I say to myself "I don't like it when other beings feel bad" enough times, eventually I might start feeling bad when shrimp's eyestalks are ablated, even though I didn't feel that way originally. I mean this is a somewhat cartoonish and simple example.

But seems reasonable to me that value formation in humans (meaning, the things that were functionally optimizing for when we're acting coherently) works that way. And seems plausible that value formation in LLMs would also work this way.

I haven't thought of any experiments to test this though.

AI could replace doctors but not nurses.

We will almost certainly see more and more people use AI for health advice. This substitutes away from asking an actual doctor. It seems quite possible that this would lead to reduced demand for doctors but increased demand for nurses, who provide a lot of the hard to automate care and administer tests.

There could be a general social dynamic in multiple different sectors where the roles that are traditionally more high-status/brain-y are more disrupted by AI compared to their less high status counterparts. People have talked about this dynamic happening sort of across labor sectors (e.g. white v. blue collar work), but we will probably also see this within sectors (e.g., doctors versus nurses). I'm not sure what sociopolitical/cultural implications will arise if nurses all of a sudden make more than the doctors that they've worked together with this whole time.

Although it's not impossible for overall demand for medical care to go up enough to compensate the drop. Alternatively, it's also not impossible that more accurate diagnosis from AI doctors actually substitutes away from testings since you need less tests to find out that you have a certain condition (i.e., less demand for nurses as well). Collective bargaining (i.e., unions) could also lead to wages decoupling from the marginal product of labor.

Despite all this, I think the most likely outcome is that we will see some sort of "status-switch" in some sectors.

(Idk I think this is sort of obvious but I haven't seen it cleanly written up anywhere)

Starting a shortform to keep track of tweets that I want to refer back to.

On Goodfire's hallucinations probe training, and also path dependent alignment (Feb 12, 2026)

You need to think about the supply AND demand for AI behaviors (Dec 27, 2025)

AI 2027's main contribution is the path to ASI/how to think about this progression (Dec 23, 2025)

Giving money to lightcone (Dec 15, 2025)

Do not contaminate the big beautiful pretraining corpus with human labels (Dec 14, 2025)

Simulators is the prior in LLMs and will always be relevant (Nov 23, 2025)

Russian joke about insulting the president in real life (Nov 20, 2025)

Unbounded task complexity (i.e., there are actually just a lot of things for AIs to learn) & low sample efficiency in AIs -> long timelines. (Nov 19, 2025 & Dec 21, 2025) (See also my commentary on task complexity when the METR study was first released on Mar 25, 2025)

59 page Neel Nanda MATS paper (Oct 30, 2025)

50 page Neel Nanda MATS application (Mar 3, 2025)

Agents that are capable of solving hard problems need not be consequentialist & reflectively stable (Mar 3, 2025)

Givewell girl summer (July 14, 2024)

My thesis on Fox New's Effects on Social Preferences (June 13, 2023)