Commutativity: Intuition

Commutativity as an artifact of notation

Instead of thinking of a commutative function as a function that takes an ordered pair of inputs, we can think of as a function that takes an unordered bag of inputs, and therefore can't depend on their order. On this interpretation, the fact that functions are always given inputs in a particular order is an artifact of our definitions, not a fundamental property of functions themselves. If we had notation for functions applied to arguments in no particular order, then commutative functions would be the norm, and non-commutative functions would require additional structure imposed on their inputs.

In a world of linear left-to-right notation, where means " applied to first and second", commutativity looks like a constraint. In an alternative world where functions are applied to their inputs in parallel, with none of them distinguished as "first" by default, commutativity is the natural state of affairs.

Commutativity as symmetry in how the output corresponds to the input

Commutativity can also be seen as a form of symmetry. In a commutative function, the relationship between the output and the inputs is symmetric.

Imagine a binary function as a physical mechanism of wheels and gears, that takes two inputs in along conveyer belts (one on the left, one on the right), manipulates those inputs (using mechanical sensors and manipulators and tools), and produces a result that is placed on another outgoing conveyer belt.

There are two obvious ways we can imagine the function being symmetric in its use of the inputs. First is that all the mechanisms that the function uses to combine the two inputs could be left-right symmetric: An arm on the left picks up the left input, an arm on the right picks up the right input, and the two inputs are then squished together in the middle to produce the output. For example, the function that takes two strings and puts a dot between them (e.g., ) is symmetric in this fashion, whereas the function which puts a dot in front of its two arguments () is not. This type of symmetry is not commutativity, it is associativity, which is commonly confused with commutativity.

The other obvious symmetry is that the output can be symmetric in the way it contains the inputs. The reason that the function above was not commutative is because if it gets the input "red" on the left and "blue" on the right, then it produces the output "redblue", which has all the red on one side and all the blue on the other. Though the inputs were used symmetrically, the result is asymmetric.

By contrast, a function that mixes the red and blue together — producing, for example, the unordered set — would be commutative, because the output corresponds to each input in the same way.

A function is probably commutative if you can visualize it as being implemented by a mechanism that gets one input on the left and another input on the right, and which the affect of the inputs on the output is not biased towards one side or the other.

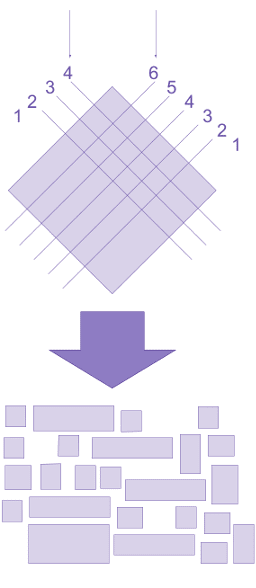

For example, we can use the following visualization to show that multiplication is commutative. Imagine a function that takes in two numbers (as stacks of poker chips), one on the left and one on the right. The function has a square of wet plaster in the middle. On each conveyer belt, an arm removes chips for the stack of poker chips until the stack only has one chip left, and for each chip that is removed, a perpendicular cut is added to the plaster (as in the diagram below). The plaster is then allowed to set, and the plaster pieces are then shaken out into a big bag. A third arm removes plaster pieces from the bag one at a time, and adds a poker chip to the outgoing conveyer belt for each one. To visualize this, see the diagram below:

Because the output contains 24 poker chips that don't necessarily come from one side or the other, multiplication commutes. (To formalize this idea, the question is, of course, whether for all and in the function's domain).