I am sure you are already aware of this, but the conserved quantities we see come from symmetries in the function space (Noether's theorem). The question I think you should be asking is, how do we extend this to random variables in information theory?

I am not sure of The Answer™, but I have an answer and I believe it is The Answer™: with the information bottleneck. Suppose we have a map from some bits in the world to some properties we care about. In my head, I'm using the example of and . If there is a symmetry in that is invariant to, this means we should lose no predictive information by transforming a sample according to that symmetry

If we already know the symmetry we can force our predictor to be invariant to it. This is most commonly seen in chemistry models where they choose graph neural networks that are invariant to vertex and edge relabeling. However, usually it is hard to specify the exact symmetries (how do you code a "seven" is symmetric to stretching out its leg a little?), and the symmetries may also not be exact (a "seven" can bleed into a "one" by shortening its arm). The solution is to first run through an autoencoder model that automatically finds these exact symmetries, and the inexact ones up to whatever bit precision you care about.

If we replace the exact by the autoencoder , then

means we want to maximize the mutual information between (the property we care about, like "sevenness") and . Also,

meaning the more symmetries captures, the smaller its entropy should be. Since probably has some fixed entropy, this is equivalent to minimizing the mutual information between and . Together, we have a tradeoff between maximizing and minimizing , which is just the information bottleneck:

The larger the the more "stochastic symmetries" are eliminated, which means it gets closer to the essence of "sevenness" or whatever properties are in , but further from saying anything else about . The fun thing you can do is make and the same entity, and now you are getting the essence of unsupervised (e.g., with MNIST, though it does have reconstruction loss too).

Finally, a little evidence that seems to align with autoencoders being the solution comes from adversarial robustness. For a decade or so, it was believed that generalization and adversarial robustness are counter to one another. This seems a little ridiculous to me now, but then again I was not old enough to be aware of the problem before the myth was dispelled (this myth has been dispelled, right? People today know that generalization and robustness are essentially the same problem, right?). Anyway, the way everyone was training for adversarial robustness is they took the training images, perturbed them as little as possible to get the model to mispredict (adversarial backprop), and then trained on these new images. This ended up making the generalization error worse ("Robustness May Be at Odds with Accuracy"). It turns out if you just first autoencode the images or use a GAN to keep the perturbations on-manifold, then it generalizes better ("Disentangling Adversarial Robustness and Generalization "). Almost like it captured the ontology better.

Perhaps relevant: An Informational Parsimony Perspective on Probabilistic Symmetries (Charvin et al 2024), on applying information bottleneck approaches to group symmetries:

... the projection on orbits of a symmetry group’s action can be seen as an information-preserving compression, as it preserves the information about anything invariant under the group action. This suggests that projections on orbits might be solutions to well-chosen rate-distortion problems, hence opening the way to the integration of group symmetries into an information-theoretic framework. If successful, such an integration could formalise the link between symmetry and information parsimony, but also (i) yield natural ways to “soften” group symmetries into flexible concepts more relevant to real-world data — which often lacks exact symmetries despite exhibiting a strong “structure” — and (ii) enable symmetry discovery through the optimisation of information-theoretic quantities.

First: Yes, this post seems to essentially be about thermodynamics and either way it is salient to immediately bring up symmetry. So agree on that point.

Symmetry, thermodynamics, information theory and ontology happen to be topics I take interest in (as stated in my LW bio).

Now, James, for your approach, I would like to understand better what you are saying here, and what you are actually claiming. Could you dumb this down or make it clearer? What scope/context do you intend for this approach? How far do you take it? And how much have you thought about it?

The tricky part when parsing John's post is understanding what he means by "insensitive functions." He doesn't define it anywhere, and I think it's because he was pointing at an idea but didn't yet have a good definition for it. However, the example he gives—conservation of energy—occurs because the laws of physics are insensitive to some kind of symmetry, in this particular case time-translation. I've been thinking a lot about the relationship symmetries + physics + information theory this past year or two, and you can see some of my progress here and here. To me, it felt kind of natural to jump to "insensitive functions" being a sort of stochastic symmetry in the data.

I haven't fleshed out exactly what that means. For exact symmetries, we can break up the data into a symmetry-invariant piece and the symmetry factor

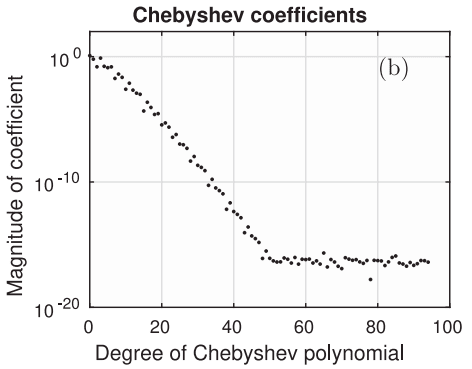

However, it feels like in real data, there is not such a clean separation. It's closer to something like this: we could write "big-edian" form, so that we get finer and finer details about as we read off more bits. My guess is there is an "elbow" in the importance of the bits, similar to how Chebyshev series have this elbow in coefficient magnitude that chebfun identifies and chops off for quicker calculations:

(Source: Chopping a Chebyshev Series)

In fact, as I'm writing this, I just realized that your autoencoder model could just be a discrete cosine (Chebyshev series) transform. It won't be the best autoencoder to exist, but it is what JPEG uses. Anyway, I think the "arm"—or the bits to the left of the elbow—seems to form a natural ontology. The bits to the left of it seem to be doing something to help describe , but not the bits to the right.

How does this relate to symmetries? Well, an exact symmetry is cleanly separable, which means the bits could be added after every other bit—it's far to the right of the elbow. Chopping off the elbow does satisfy our idea of "ontology" in the exact symmetry case. Then all we need to do is create a model that chops off those uninteresting bits. The parameter in the information bottleneck pretty much specifies a chopping point. The first term, , says to keep important bits, while the second term, says to cut out unimportant bits, and specifies at what point bits become too unimportant to leave in. You can slowly increase until things start catastrophically failing (e.g. validation loss goes down), at which point you've probably identified the elbow.

So, I feel like you just got deeper into the weeds here, thinking aloud. This seems interesting. I am trying to parse, but there is not enough formal context to make it make sense to me.

My main question was anyway, what w/could you use it for? What is the scope/context?

(Making some light banter) Maybe you are american, so I need to "debate" you to make it more obvious. "James, this is all a nice theoretical concept, but it seems useless practically. In its current form, I don't see how it could be used for anything important".

Haha, I did initially start with trying to be more explanatory but that ended after a few sentences. Where I think this could immediately improve a lot of models is by replacing the VAEs everyone is using in diffusion models with information bottleneck autoencoders. In short: VAEs are viruses. In long: VAEs got popular because they work decently well, but they are not theoretically correct. Their paper gestures at a theoretical justification, but it settles for less than is optimal. They do work better than vanilla autoencoders, because they "splat out" encodings which lets you interpolate between datapoints smoothly, and this is why everyone uses them today. If you ask most people using them, they will tell you it's "industry standard" and "the right way to do things, because it is industry standard." An information bottleneck autoencoder also ends up "splatting out" encodings, but has the correct theoretical backing. My expectations are you will automatically get things like finer details and better instruction following ("the table is on the apple"), because bottleneck encoders have more pressure to conserve encoding bits for such details.

There are probably a few other places this would be useful—for example, in LLM autoregression, you should try to minimize the mutual information between the embeddings and the previous tokens—but I have yet to do any experiments in other places. This is because estimating the mutual information is hard and makes training more fragile.

In terms of just philosophy, well I don't particularly care for just the subject of philosophy. Philosophers too often assign muddy meanings to words and wonder why they're confused ten propositions in. My goal when interacting with such sophistry is usually to define the words and figure out what that entails. I think philosophers just do not have the mathematical training to put into words what they mean, and even with that training it's hard to do and will often be wrong. For example, I do not think the information bottleneck is a proper definition of "ontology" but is closer to "describing an ontology". It does not say why something is the way it is, but it helps you figure out what it is. It's a way to find natural ontologies, but does not say anything about how they came to be.

Thank you, just knowing you are strictly coming from a ML perspective already helps a lot. This was not obvious to me, who have approached these topics more from a physics lens.

//

So, addressing your implementation ideas, this approach is practically speaking pretty neat! I lack formal ML background to properly evaluate it, but it seems neat.

Now, I will try to succinctly decipher the theory behind your core idea, and you let me know how I do.

You propose compressing data into a form that preserves the core identity. It gives us something practical we can work with.

The elbow has variables that break symmetry to the left and variables that hold symmetry to the right. This is an important distinction between from* noise and signal that I think many miss.

*mended, edit

This is all context dependent? Context defines the curve, the parameter.

// How did I do?

Note: I should say at this point, understanding fundamental reality is my lifelong quest (constantly ignored in order to live out my little side quests) and I care about this topic. This quest, is what ontology means in the classical, and philosophical sense. When I speak about ontology in AI-context, I usually mean formal representations of reality, not induced ones. You seem to use AI context but mean induced ontologies.

The 'ontology as insensitivity' concept described by johnswentworth is interesting, and basically follows from statistical mechanics. But it is perhaps missing the inherent symmetry aspect, or something replacing it, as a fundamental factor. You can't remove all symmetry. Everything with identity exists within a symmetry. This is non-obvious and partly my own assertion, but looking at modern group theory, this is indeed how mathematics define objects and so I am supported within this framework.

If we take wentworth's idea and your elbow analogy, and try to define an object within a formal ontology, within my framework that all objects exist within symmetries, then we get:

The "Elbow" doesn't mark where reality ends and noise begins. It marks the resolution limit of your current context.

- To the left of the elbow: Information that matters (Differences).

- To the right of the elbow: Information that doesn't matter (Equivalences/Symmetries).

Your example was a hand-written digit "7". The Tail is the symmetries. You can slant the digit, thicken the line, or shift it left. These are the symmetries. As long as the variation stays in the "tail" of the curve, the identity "7" is preserved. (Note that the identity is relative and context dependent).

The Elbow: This is the breaking point. If you bend the top horizontal line too much, it becomes a "1". You have left the chosen symmetry group of "7" and entered the chosen symmetry group of "1".

This is mostly correct, though I think there are phase changes making some more natural than others.

If so, I would be genuinely curious to hear your ideas here. This might be an actually powerful concept if it holds up and you can formalize it properly. I assume you are an engineer, not a scientist? I think this idea deserves some deep thinking.

I don't have any more thoughts on this at present, and I probably won't think too much on it in the future, as it isn't super interesting to me.

Something which I think highly relevant, and which might inform your GAN discussion, is the difference in performance of W-GAN - basically if you train the GAN using an optimal transport metric instead of an information theoretic one, it seems to have much better robustness properties, and this is probably because shannon entropy doesn't respect continuity of your underlying metric space (e.g. KL divergence between Delta(x0) and Delta(x0 + epsilon) is infinity for any nonzero epsilon, so it doesnt capture 'closeness'). I don't yet know how I think this should tie into the high-probability latent manifold story you tell, but it seems like part of it.

Have you heard of Rene Thom's work on Structural Stability and Morphogenesis? I haven't been able to read this book yet[1], but my understanding[2] of its thesis is that: "development of form" (i.e. morphogenesis, broadly construed, eg biological or otherwise) depends on information from the structurally stable "catastrophe sets" of the potential driving (or derived from) the dynamics - structurally stable ones, precisely because what is stable under infinitesimal perturbation are the only kind of information observable in nature.

Rene Thom puts all of this in a formal model - and, using tools of algebraic topology, show that these discrete catastrophes (under some conditions, like number of variables) have a finite classification, and thus (in the context of this morphological model) is a sort of finitary "sufficient statistics" of the developmental process.

This seems quite similar to the point you're making: [insensitive / stable / robust] things are rare, but they organize the natural ontology of things because they're the only information that survives.

... and there seems to be the more speculative thesis of Thom (presumably; again, I don't know this stuff), where geometric information about these catastrophes directly correspond to functional / internal-structure information about the system (in Thom's context, the Organism whose morphogenic process we're modeling) - this presumably is one of the intellectual predecessors of Structural Bayesianism, the thesis that there is a correspondence between internal structures of Programs or the Learning Machine with the local geometry of some potential.

- ^

I don't think I have enough algebraic topology background yet to productively read this book. Everything in this comment should come with Epistemic Status: Low Confidence.

- ^

From discussions and reading distillations of Thom's work.

I agree Thom's work is interesting and relevant here; I've seen it bruited about a lot, but likewise haven't gotten around to seriously studying it. From my perspective, structural stability is extremely important, but I am curious if there is any reason to identify this kind of stability with catastrophes? I've always looked at the classification and figured its just one example of this kind of structural stability, and not one I've really even seen much of in physics, compared to the I-think-close-but-not-exactly-the-same more general idea of critical phenomena and phase transitions. I'd be very interested if there was some sort of RG-based stability analysis.

The dynamical systems way of framing this I like the most is Koopman analysis; Steve Brunton has a great family of talks on on youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J7s0XNT96ag

Tldr is that the Koopman operator evolves functions of the dynamical variables; it's an infinite dimensional linear operator, thus it has eigenfunctions and eigenvalues. Conserved functions of state have zero-eigenvalue; nearly conserved quantities have 'small' eigenvalues, corresponding to a slower time rate of decay. Then you can characterise all functions in terms of the decay rate of their self-correlation. So the dominant koopman eigenvalue of a (not necessarily eigenfunction) is a scalar value corresponding to how "not conserved" it is.

You can also look at the Jordan blocks, which correspond to groups of functions which are predictively closed (you can predict their future values by knowing only the present values of those functions). These are some threads I've found interesting in thinking about natural ontology but I do not think they are sufficient - for example they give a very clear picture of intra-realization correlations, but do not have a good way of talking about inter-realization correlations or sensitivity to initial conditions.

The most canonical example of a "natural ontology" comes from gasses in stat mech. In the simplest version, we model the gas as a bunch of little billiard balls bouncing around in a box.

The dynamics are chaotic. The system is continuous, so the initial conditions are real numbers with arbitrarily many bits of precision - e.g. maybe one ball starts out centered at x = 0.8776134000327846875..., y = 0.0013617356590430716..., z=132983270923481... . As balls bounce around, digits further and further back in those decimal representations become relevant to the large-scale behavior of the system. (Or, if we use binary, bits further and further back in the binary representations become relevant to the large-scale behavior of the system.) But in practice, measurement has finite precision, so we have approximately-zero information about the digits/bits far back in the expansion. Over time, then, we become maximally-uncertain about the large-scale behavior of the system.

... except for predictions about quantities which are conserved - e.g. energy.

Conversely, our initial information about the large-scale system behavior still tells us a lot about the future state, but most of what it tells us is about bits far back in the binary expansion of the future state variables (i.e. positions and velocities). Another way to put it: initially we have very precise information about the leading-order bits, but near-zero information about the lower-order bits further back. As the system evolves, these mix together. We end up with a lot of information about the leading-order and lower-order bits combined, but very little information about either one individually. (Classic example of how we can have lots of information about two variables combined but little information about either individually: I flip two coins in secret, then tell you that the two outcomes were the same. All the information is about the relationship between the two variables, not about the individual values.) So, even though we have a lot of information about the microscopic system state, our predictions about large-scale behavior (i.e. the leading-order bits) are near-maximally uncertain.

... again, except for conserved quantities like energy. We may have some initial uncertainty about the energy, or there may be some noise from external influences, etc, but the system’s own dynamics will not "amplify" that uncertainty the way it does with other uncertainty.

So, while most of our predictions become maxentropic (i.e. maximally uncertain) as time goes on, we can still make reasonably-precise predictions about the system’s energy far into the future.

That's where the natural ontology comes from: even a superintelligence will have limited precision measurements of initial conditions, so insofar as the billiard balls model is a good model of a particular gas even a superintelligence will make the same predictions about this gas that a human scientist would. It will measure and track conserved quantities like the energy, and then use a maxent distribution subject to those conserved quantities - i.e. a Boltzmann distribution. That's the best which can realistically be done.

Emphasizing Insensitivity

In the story above, I tried to emphasize the role of sensitivity. Specifically: whatever large-scale predictions one might want to make (other than conserved quantities) are sensitive to lower and lower order bits/digits, over time. In some sense, it's not really about the "size" of things, it's not really about needing more and more precise measurements. Rather, the reason chaos induces a natural ontology is because non-conserved quantities of interest depend on a larger and larger number of bits as we predict further and further ahead. There are more and more bits which we need to know, in order to make better-than-Boltzmann-distribution predictions.

Let's illustrate the idea from a different angle.

Suppose I have a binary function f, with a million input bits and one output bit. The function is uniformly randomly chosen from all such functions - i.e. for each of the 21000000 possible inputs x, we flipped a coin to determine the output f(x) for that particular input.

Now, suppose I know f (i.e. I know the output produced by each input), and I know all but 50 of the input bits - i.e. I know 999950 of the input bits. How much information do I have about the output?

Answer: almost none. For almost all such functions, knowing 999950 input bits gives us ∼1250 bits of information about the output. More generally, If the function has n input bits and we know all but k, then we have o(12k) bits of information about the output. (That’s “little o” notation; it’s like big O notation, but for things which are small rather than things which are large.) Our information drops off exponentially with the number of unknown bits.

Proof Sketch

With k input bits unknown, there are 2k possible inputs. The output corresponding to each of those inputs is an independent coin flip, so we have 2k independent coin flips. If m of those flips are 1, then we assign a probability of m2k that the output will be 1.

As long as 2k is large, Law of Large Numbers will kick in, and very close to half of those flips will be 1 almost surely - i.e. m≈ 2k2. The error in this approximation will (very quickly) converge to a normal distribution, and our probability that the output will be 1 converges to a normal distribution with mean 12 and standard deviation 12k/2. So, the probability that the output will be 1 is roughly 12±12k/2.

We can then plug that into Shannon’s entropy formula. Our prior probability that the output bit is 1 is 12, so we’re just interested in how much that ±12k/2 adjustment reduces the entropy. This works out to o(12k) bits.

The effect here is similar to chaos: in order to predict the output of the function better than 50/50, we need to know basically-all of the input bits. Even a relatively small number of unknown bits - just 50 out of 1000000 - is enough to wipe out basically-all of our information and leave us basically back at the 50/50 prediction.

Crucially, this argument applies to random binary functions - which means that almost all functions have this property, at least among functions with lots of inputs. It takes an unusual and special function to not lose basically-all information about its output from just a few unknown inputs.

In the billiard balls case, the "inputs" to our function would be the initial conditions, and the "outputs" would be some prediction about large-scale system behavior at a later time. The chaos property very roughly tells us that, as time rolls forward enough, the gas-prediction function has the same key property as almost all functions: even a relatively small handful of unknown inputs is enough to totally wipe out one's information about the outputs. Except, of course, for conserved quantities.

Characterization of Insensitive Functions/Predictions?

Put this together, and we get a picture with a couple pieces:

So if natural ontologies are centrally about insensitive functions, and nearly all functions are sensitive... seems maybe pretty useful to characterize insensitive functions?

This has been done to some extent in some narrow ways - e.g. IIRC there's a specific sense in theory of computation under which the "least sensitive" binary functions are voting functions, i.e. each input bit gets a weight (positive or negative) and then we add them all up and see whether the result is positive or negative.

But for natural ontology purposes, we'd need a more thorough characterization. Some way to take any old function - like e.g. the function which predicts later billard-ball-gas state from earlier billiard-ball-gas-state - and quantitatively talk about its "conserved quantities"/"insensitive quantities" (or whatever the right generalization is), "sensitive quantities", and useful approximations when some quantities are on a spectrum between fully sensitive and fully insensitive.