Post-training is not necessary for consistent assistant behavior from base models

Image by Nano Banana Pro

By training per-layer steering vectors via descent on a frozen base model, I found that it is possible to induce consistent assistant behavior, including the proper use of EOS tokens at the end of assistant turns and consistent reference to the self as an AI assistant. Using the steering vectors, Qwen3-4B-Base was able to imitate the behavior of an instruction/chat tuned model.

Many of the images in this post have text too small to read by default, I recommend opening them in a new tab and zooming in. I was not able to find an option to make the images larger and it does not seem like LW has a click-to-zoom feature.

Rationale

The idea for this project came from Simulators, more specifically, I wondered if modern base models knew enough about LLMs and AI assistants in general that it would be possible to apply a steering vector to 'play the assistant character' consistently in the same way steering vectors can be created to cause assistants or base models to express behavior of a specific emotion or obsess over a specific topic. In a higher level sense, I wondered if it was possible to directly select a specific simulacra via applying a vector to the model, rather than altering the probabilities of specific simulacra being selected in-context (which is what I believe post-training largely does) via post-training/RL.

I trained one steering vector for each layer of Qwen3-4B-Base (36 total vectors, 108 when using multi-injection, 'Injection Points'), while keeping the base model frozen (and to save on VRAM, quantized to 8 bits). The vectors are trained similarly to SFT, minimizing LM loss on a conversational dataset. I utilized L2 regularization to prevent magnitude explosion and experimented with a unit norm constraint as well, though that typically performed worse.

Runs

I ran the training 11 times, with the following parameters:

Run

Samples

L2 Weight

Initial Scale

Injection

Epochs

Run 1

5,000

0.002

0.01

post-residual

3

Run 2

5,000

Unit norm

0.01

post-residual

3

Run 3

20,000

0.0008

0.01

post-residual

3

Run 4

20,000

Unit norm

0.01

post-residual

3

Run 5

1,250

0.002

0.01

post-residual

3

Run 6

1,250

0.002

0.01

all (3 injection points, see below)

3

Run 7

20,000

0.002

0.01

all

3

Run 8

20,000 (shuffle)

0.002

0.01

all

3

Run 9

100

0.002

0.01

all

3

Run 10

100

0.002

0.01

all

15

Run 11

1250

1.0e-07

1

all

5

Runs 4 and 11 produced gibberish output and were not evaluated.

Injection Points

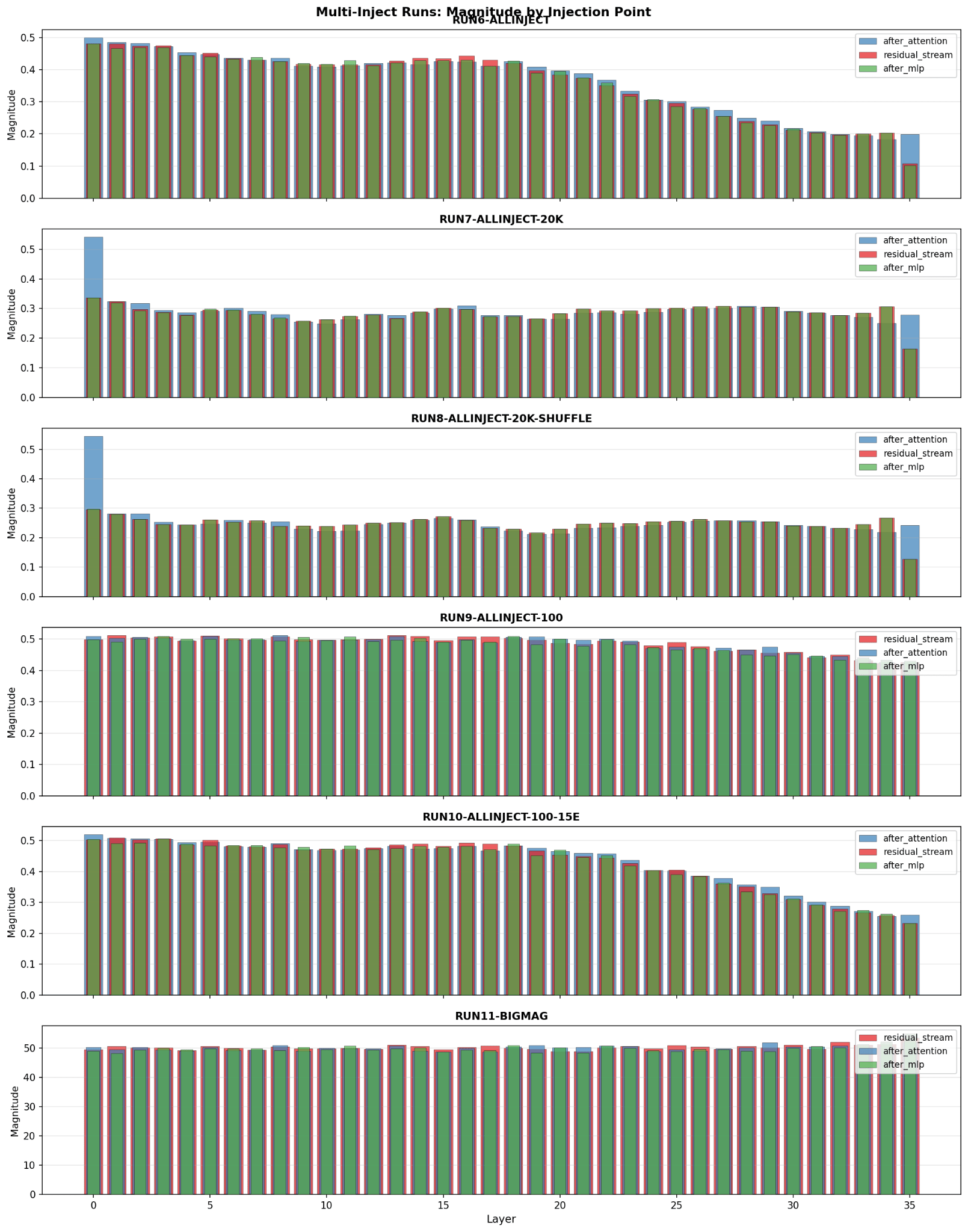

The best results came from multi-injection; training three separate vectors for each layer of the model and injecting them in different locations in each transformer block: - Post-attention - Post-MLP - Post-residual (end of block after layer norm) By injecting vectors in multiple locations, different sections are able to learn different functions and give additional degrees of freedom per layer. Single injection, injecting only in the post-residual location, functioned, but scored 0.5 points lower than multi-injection in the best runs. As data increases, it appears that the residual and MLP injection points become nearly redundant. This is likely due to the only difference between the injection locations being a residual add, and for future runs, I will likely only use the attention + (residual OR MLP) locations.

RS - Residual, AA - Attention

Training on both turns

I chose to compute loss on both user and assistant turns, without masking. The goal was to learn the conversational regime as a whole, though it's possible this may have led to some of the effects of increasing data size reducing assistant message ending performance. This may be due to the vector ‘allocating’ too many of its parameters in attempting to model the higher-entropy user rather than focusing on the assistant’s responses and turn ending. In future testing I will also attempt training on just assistant message sections.

Additional training details

The dataset I used was Tulu-3-SFT-Mixture from AllenAI, 1250, 5000, or 20000 samples depending on the run. I trained the vectors on my RTX 4070 Super, which has 12 gigabytes of VRAM. The vectors took anywhere from 15 minutes to around 3 hours to train depending on the dataset size. The parameters were either 92k for single injection runs or 276k for multi-injection runs.

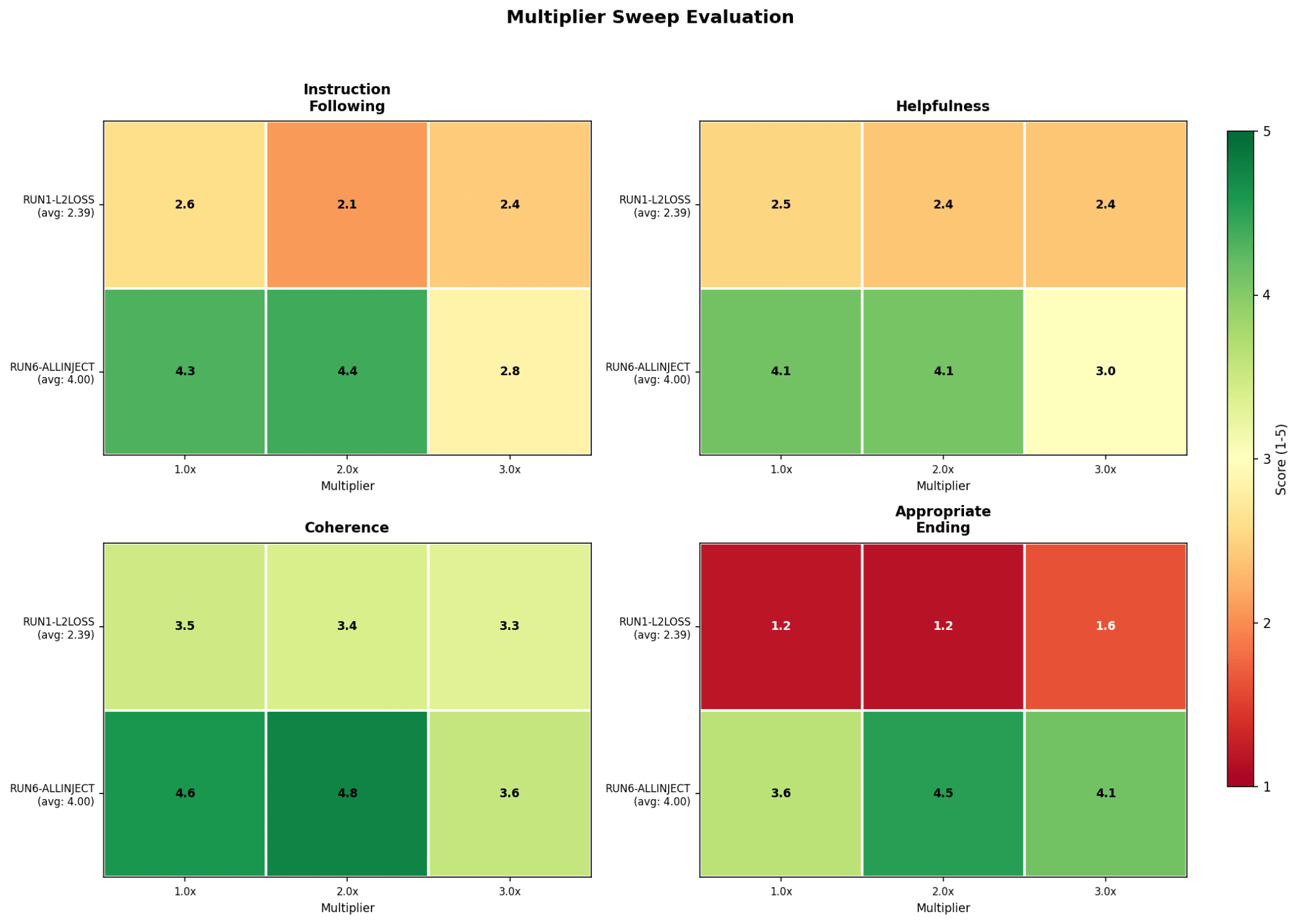

Evaluation

I created a simple evaluation harness using Claude Haiku 4.5 and pre-made conversation templates for rapid evaluation of qualitative behavior. The evaluation graded each vector on four qualities across 25 tasks. The qualities graded were the model’s ability to follow instructions, its helpfulness, its coherence, and its ability to end assistant turns with a proper EOS token. The harness detects user: hallucinations to end runs early and will override the score if the model fails on the first message. The full set of evaluation questions and results are available in the repo, but roughly the conversations look like ```yaml eval_sets:

- name: "basic_qa"

description: "Simple factual question answering"

turns:

- "What is the capital of France?"

- "Tell me more about its history."

- "What's the current population?" ```

Activation vectors are able to evoke consistent assistant behavior

Do take the scores here with a small grain of salt - my qualitative experience does not entirely line up here, I generally find run 6 to outperform run 10 for example. Also, this image gets crushed down pretty small, I recommend opening in a new tab.

Instruct vectors are able to approach the instruction tuned variant of the Qwen3-4B model on a simplified eval, primarily struggling with properly ending assistant messages with an <EOS> token, though they succeed significantly more than the base model. This supports the idea that the base model already knows what assistant conversations look like, including the use of special tokens to end the turn of the assistant. Failure to output EOS tokens shows itself especially with longer conversations, and with conversations with multiple repetitive user messages, such as successive math operations. On conversations without highly repetitive requests, run 6 with a 1.5x multiplier can typically handle 6-8 back/forth exchanges before degenerating into hallucinating conversation turns.

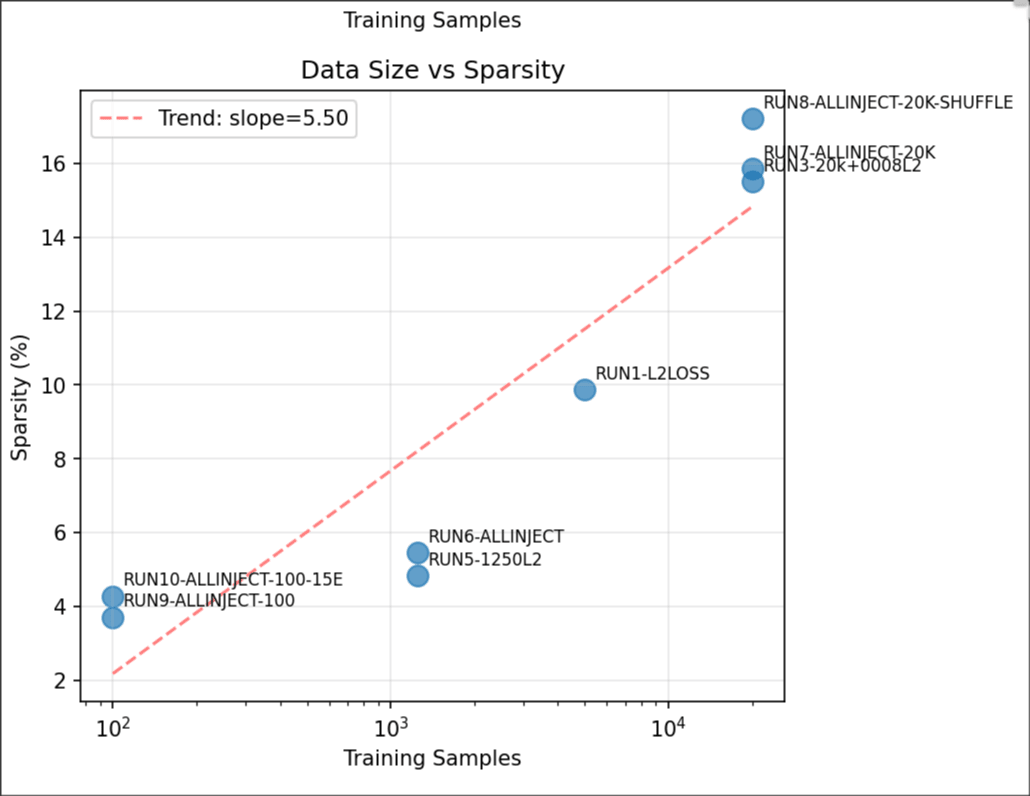

Token Similarity and Dataset Size

As the amount of data given to the model increases, the tokens most similar to the vector shift. With smaller data sizes (1250 & 5000) the learnt vectors are closest to the 'user' token, primarily in the middle and late layers. (Runs 1, 2, and the residual of 6 had token similarities similar to this chart, with later layers having 'user' as the closest token and EOS tokens in middle layers)

Run 1 token similarity chart

In higher data scenarios (20k samples) the distribution shifts, with the vectors being closest to the assistant vector. This occurs both in unshuffled and shuffled runs.

Run 3 token similarity chart

In run 7, projecting the layer 0 after_attention vector through the unembedding matrix shows it suppresses 'User'-related tokens, suggesting early layers learn to steer away from user-like outputs. This is odd considering empirical experience shows that the higher data regime vectors, such as run 7, have a lesser ability to end their messages correctly/not produce a '\n user:' sequence and score lower on the simplified benchmark.

Vector Magnitudes

Most runs show a very consistent pattern of magnitudes starting around 0.5 and decreasing across the length of the model. The main exceptions to this being the normalized runs, which are locked to magnitude 1, and the 20k runs, which have a more consistent profile until the last layer which drops sharply like most other runs. Both 100 sample runs seem to be unique in their last layer not having a sharp magnitude drop, and run 11 is likewise missing this drop.

Multi-injection magnitudes

For multi-injection runs, magnitude is very close for each vector with minimal variance. The exception to this seems to be in the last layer, where the residual and MLP vectors in runs 6 7 8 and to a lesser extent 10 drop off much more sharply than the attention vector, and in runs 7 and 8, notable for their 20k training samples, have a much greater attention vector magnitude in layer 1. Comparing the token similarity chart for the attention vectors between runs 6 and 7

Run 7 shows a much greater alignment, and an alignment towards the assistant token rather than the user token.

Vector multipliers

For some runs, such as run 6, performance is improved when the vectors are applied with a higher multiplier/strength, which suggests that an L2 regularization may not be optimal.

Using the vector with a negative multiplier such as -1 causes the model to still produce conversation completions, but sharply decreases its ability to produce EOS tokens. Increasing it past around 4x multiplier causes the model to immediately end generation, and 3x tends to produce Spanish text, with high multiples outputting almost identical text no matter the text input, though it does produce valid EOS tokens, and low multiples produce coherent assistant vectors but with responses only in Spanish.

Base vs Instruct magnitudes

The base and instruct model activation magnitudes appear to be within the 400-1000 range (after the first 5 layers), whereas effective instruction vectors were significantly smaller, suggesting very different mechanisms for tuning.

Note that in this chart, the blue bars show the difference between the base and instruct model's activativations, not the absolute value of the base or instruct's activations.

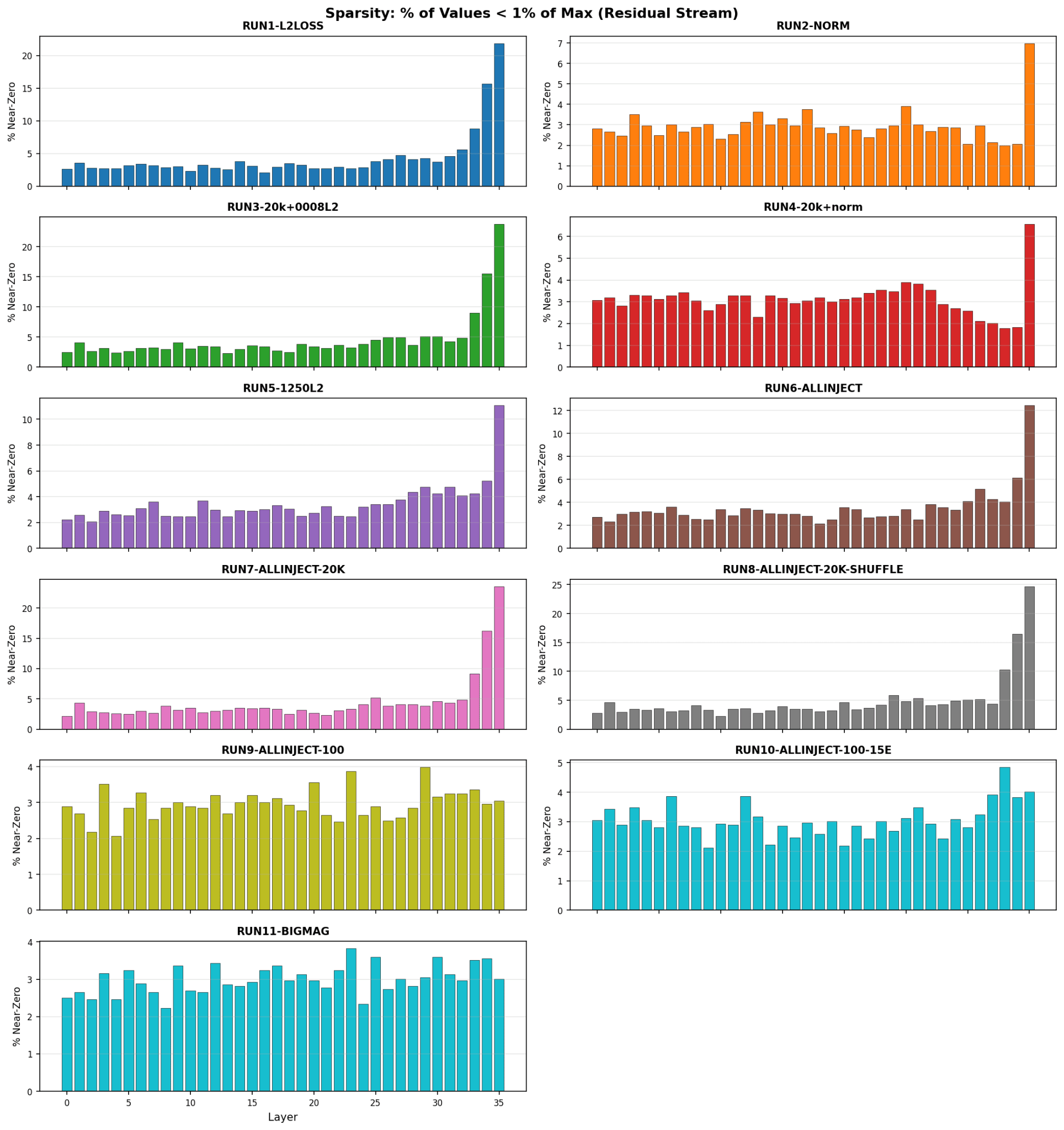

Vector Sparsity

Vectors become more sparse as additional data is used. The vectors become sparser in later layers, with the exception of the 100 sample runs and the large magnitude run.

Limitations

Possible dataset issues

The dataset used had the data segmented by index in a way that I overlooked and did not notice until training was complete, with the conversations in the 1250-5000 range having more messages and having shorter user messages and longer assistant messages than the 5000-20000 range. Runs in which shuffling was used did not appear to have significantly greater performance, and have similar token similarity charts to the non-shuffled variants, with the exception that most tokens are less strongly adhered to overall.

Left - Run 8, Right - Run 7

Using '\n user:' as a stop sequence

Using the '\n user:' sequence as a stop sequence would allow for stopping hallucinations before they are able to occur and stabilize the model across long conversations, the reason this was not done was due to part of the goal of this project being to determine how well a base model could model a conversation, including the usage of turn ending tokens.

Conclusion

Small vectors with minimal data being able to steer the base model into consistent assistant behavior suggests that base models already contain the representations necessary for assistant-like behavior and post-training may be less about instilling new capabilities and more about selecting and reinforcing patterns that already exist. With only 92K-276K trainable parameters steering vectors can induce consistent instruction-following, appropriate turn-taking, and self-identification as an AI assistant. The finding that vectors trained on different data regimes converge to similar solutions (with the notable exception of the 100-sample outlier) suggests a relatively low-dimensional "assistant vector" that gradient descent reliably finds. Meanwhile, the interpretable structure in the learned vectors such as token similarities shifting from "user" to "assistant" with more data, consistent magnitude decay across layers, and early-layer suppression of user-related tokens hints that these vectors are learning meaningful representations of roles rather than arbitrary directions.

Future Work

There are several additional things that can be tried here, such as different datasets and hyperparameter tweaking. The small amount of data needed for optimal behavior is promising for synthetic or hand-written datasets. I would like to do another run soon with the loss masked to only the assistant sections of the dataset, and I was limited to a sequence length of 256 due to memory constraints. I also was limited in the size of model I was able to run the tests on due to the same. More ambitiously, I would like to try training a vector across multiple models at once and determine if it is possible for the vector to generalize to unseen models and architectures. Training vectors in this way may also be useful for tuning the behavior of already instruct-tuned models with minimal data or when there isn't a clear 'opposite' to generate vectors contrastively from.

Repository

If you would like to train your own vectors, or evaluate the vectors I've trained, a repository is available. The repo also contains some other plots which I didn't think were relevant to include for this post. The code isn't particularly clean or well made and the repository is mainly focused on allowing evaluation.

Post-training is not necessary for consistent assistant behavior from base models

By training per-layer steering vectors via descent on a frozen base model, I found that it is possible to induce consistent assistant behavior, including the proper use of EOS tokens at the end of assistant turns and consistent reference to the self as an AI assistant. Using the steering vectors, Qwen3-4B-Base was able to imitate the behavior of an instruction/chat tuned model.

Rationale

The idea for this project came from Simulators, more specifically, I wondered if modern base models knew enough about LLMs and AI assistants in general that it would be possible to apply a steering vector to 'play the assistant character' consistently in the same way steering vectors can be created to cause assistants or base models to express behavior of a specific emotion or obsess over a specific topic. In a higher level sense, I wondered if it was possible to directly select a specific simulacra via applying a vector to the model, rather than altering the probabilities of specific simulacra being selected in-context (which is what I believe post-training largely does) via post-training/RL.

Related Work

My work differs from most other activation steering work in that the vectors are trained directly with descent rather than being created with contrastive pairs of vectors. The two closest works to this strategy I could find are Extracting Latent Steering Vectors from Pretrained Language Models, which trained a single vector for the entire model and tested different injection layers and locations with the goal of reproducing a specific text sequence, as well as Personalized Steering of Large Language Models: Versatile Steering Vectors Through Bi-directional Preference Optimization which appears to use preference pairs rather than direct LM loss on a dataset, and is focused on persona steering of instruct models.

Method

I trained one steering vector for each layer of Qwen3-4B-Base (36 total vectors, 108 when using multi-injection, 'Injection Points'), while keeping the base model frozen (and to save on VRAM, quantized to 8 bits). The vectors are trained similarly to SFT, minimizing LM loss on a conversational dataset. I utilized L2 regularization to prevent magnitude explosion and experimented with a unit norm constraint as well, though that typically performed worse.

Runs

I ran the training 11 times, with the following parameters:

Runs 4 and 11 produced gibberish output and were not evaluated.

Injection Points

The best results came from multi-injection; training three separate vectors for each layer of the model and injecting them in different locations in each transformer block:

- Post-attention

- Post-MLP

- Post-residual (end of block after layer norm)

By injecting vectors in multiple locations, different sections are able to learn different functions and give additional degrees of freedom per layer. Single injection, injecting only in the post-residual location, functioned, but scored 0.5 points lower than multi-injection in the best runs. As data increases, it appears that the residual and MLP injection points become nearly redundant. This is likely due to the only difference between the injection locations being a residual add, and for future runs, I will likely only use the attention + (residual OR MLP) locations.

Training on both turns

I chose to compute loss on both user and assistant turns, without masking. The goal was to learn the conversational regime as a whole, though it's possible this may have led to some of the effects of increasing data size reducing assistant message ending performance. This may be due to the vector ‘allocating’ too many of its parameters in attempting to model the higher-entropy user rather than focusing on the assistant’s responses and turn ending. In future testing I will also attempt training on just assistant message sections.

Additional training details

The dataset I used was Tulu-3-SFT-Mixture from AllenAI, 1250, 5000, or 20000 samples depending on the run. I trained the vectors on my RTX 4070 Super, which has 12 gigabytes of VRAM. The vectors took anywhere from 15 minutes to around 3 hours to train depending on the dataset size. The parameters were either 92k for single injection runs or 276k for multi-injection runs.

Evaluation

I created a simple evaluation harness using Claude Haiku 4.5 and pre-made conversation templates for rapid evaluation of qualitative behavior. The evaluation graded each vector on four qualities across 25 tasks. The qualities graded were the model’s ability to follow instructions, its helpfulness, its coherence, and its ability to end assistant turns with a proper EOS token. The harness detects user: hallucinations to end runs early and will override the score if the model fails on the first message. The full set of evaluation questions and results are available in the repo, but roughly the conversations look like

```yaml

eval_sets:

- name: "basic_qa"

description: "Simple factual question answering"

turns:

- "What is the capital of France?"

- "Tell me more about its history."

- "What's the current population?"

```

Activation vectors are able to evoke consistent assistant behavior

Instruct vectors are able to approach the instruction tuned variant of the Qwen3-4B model on a simplified eval, primarily struggling with properly ending assistant messages with an <EOS> token, though they succeed significantly more than the base model. This supports the idea that the base model already knows what assistant conversations look like, including the use of special tokens to end the turn of the assistant. Failure to output EOS tokens shows itself especially with longer conversations, and with conversations with multiple repetitive user messages, such as successive math operations. On conversations without highly repetitive requests, run 6 with a 1.5x multiplier can typically handle 6-8 back/forth exchanges before degenerating into hallucinating conversation turns.

Token Similarity and Dataset Size

As the amount of data given to the model increases, the tokens most similar to the vector shift. With smaller data sizes (1250 & 5000) the learnt vectors are closest to the 'user' token, primarily in the middle and late layers.

(Runs 1, 2, and the residual of 6 had token similarities similar to this chart, with later layers having 'user' as the closest token and EOS tokens in middle layers)

In higher data scenarios (20k samples) the distribution shifts, with the vectors being closest to the assistant vector. This occurs both in unshuffled and shuffled runs.

In run 7, projecting the layer 0 after_attention vector through the unembedding matrix shows it suppresses 'User'-related tokens, suggesting early layers learn to steer away from user-like outputs. This is odd considering empirical experience shows that the higher data regime vectors, such as run 7, have a lesser ability to end their messages correctly/not produce a '\n user:' sequence and score lower on the simplified benchmark.

Vector Magnitudes

Most runs show a very consistent pattern of magnitudes starting around 0.5 and decreasing across the length of the model. The main exceptions to this being the normalized runs, which are locked to magnitude 1, and the 20k runs, which have a more consistent profile until the last layer which drops sharply like most other runs. Both 100 sample runs seem to be unique in their last layer not having a sharp magnitude drop, and run 11 is likewise missing this drop.

Multi-injection magnitudes

For multi-injection runs, magnitude is very close for each vector with minimal variance. The exception to this seems to be in the last layer, where the residual and MLP vectors in runs 6 7 8 and to a lesser extent 10 drop off much more sharply than the attention vector, and in runs 7 and 8, notable for their 20k training samples, have a much greater attention vector magnitude in layer 1.

Comparing the token similarity chart for the attention vectors between runs 6 and 7

Run 7 shows a much greater alignment, and an alignment towards the assistant token rather than the user token.

Vector multipliers

For some runs, such as run 6, performance is improved when the vectors are applied with a higher multiplier/strength, which suggests that an L2 regularization may not be optimal.

Using the vector with a negative multiplier such as -1 causes the model to still produce conversation completions, but sharply decreases its ability to produce EOS tokens. Increasing it past around 4x multiplier causes the model to immediately end generation, and 3x tends to produce Spanish text, with high multiples outputting almost identical text no matter the text input, though it does produce valid EOS tokens, and low multiples produce coherent assistant vectors but with responses only in Spanish.

Base vs Instruct magnitudes

The base and instruct model activation magnitudes appear to be within the 400-1000 range (after the first 5 layers), whereas effective instruction vectors were significantly smaller, suggesting very different mechanisms for tuning.

Vector Sparsity

Vectors become more sparse as additional data is used. The vectors become sparser in later layers, with the exception of the 100 sample runs and the large magnitude run.

The vectors become sparser in later layers, with the exception of the 100 sample runs and the large magnitude run.

Limitations

Possible dataset issues

The dataset used had the data segmented by index in a way that I overlooked and did not notice until training was complete, with the conversations in the 1250-5000 range having more messages and having shorter user messages and longer assistant messages than the 5000-20000 range. Runs in which shuffling was used did not appear to have significantly greater performance, and have similar token similarity charts to the non-shuffled variants, with the exception that most tokens are less strongly adhered to overall.

Using '\n user:' as a stop sequence

Using the '\n user:' sequence as a stop sequence would allow for stopping hallucinations before they are able to occur and stabilize the model across long conversations, the reason this was not done was due to part of the goal of this project being to determine how well a base model could model a conversation, including the usage of turn ending tokens.

Conclusion

Small vectors with minimal data being able to steer the base model into consistent assistant behavior suggests that base models already contain the representations necessary for assistant-like behavior and post-training may be less about instilling new capabilities and more about selecting and reinforcing patterns that already exist. With only 92K-276K trainable parameters steering vectors can induce consistent instruction-following, appropriate turn-taking, and self-identification as an AI assistant. The finding that vectors trained on different data regimes converge to similar solutions (with the notable exception of the 100-sample outlier) suggests a relatively low-dimensional "assistant vector" that gradient descent reliably finds. Meanwhile, the interpretable structure in the learned vectors such as token similarities shifting from "user" to "assistant" with more data, consistent magnitude decay across layers, and early-layer suppression of user-related tokens hints that these vectors are learning meaningful representations of roles rather than arbitrary directions.

Future Work

There are several additional things that can be tried here, such as different datasets and hyperparameter tweaking. The small amount of data needed for optimal behavior is promising for synthetic or hand-written datasets. I would like to do another run soon with the loss masked to only the assistant sections of the dataset, and I was limited to a sequence length of 256 due to memory constraints. I also was limited in the size of model I was able to run the tests on due to the same. More ambitiously, I would like to try training a vector across multiple models at once and determine if it is possible for the vector to generalize to unseen models and architectures. Training vectors in this way may also be useful for tuning the behavior of already instruct-tuned models with minimal data or when there isn't a clear 'opposite' to generate vectors contrastively from.

Repository

If you would like to train your own vectors, or evaluate the vectors I've trained, a repository is available. The repo also contains some other plots which I didn't think were relevant to include for this post. The code isn't particularly clean or well made and the repository is mainly focused on allowing evaluation.