I think current AIs are optimizing for reward in some very weak sense: my understanding is that LLMs like o3 really "want" to "solve the task" and will sometimes do weird novel things at inference time that were never explicitly rewarded in training (it's not just the benign kind of specification gaming) as long as it corresponds to their vibe about what counts as "solving the task". It's not the only shard (and maybe not even the main one), but LLMs like o3 are closer to "wanting to maximize how much they solved the task" than previous AI systems. And "the task" is more closely related to reward than to human intention (e.g. doing various things to tamper with testing code counts).

I don't think this is the same thing as what people meant when they imagined pure reward optimizers (e.g. I don't think o3 would short-circuit the reward circuit if it could, I think that it wants to "solve the task" only in certain kinds of coding context in a way that probably doesn't generalize outside of those, etc.). But if the GPT-3 --> o3 trend continues (which is not obvious, preventing AIs that want to solve the task at all costs might not be that hard, and how much AIs "want to solve the task" might saturate), I think it will contribute to making RL unsafe for reasons not that different from the ones that make pure reward optimization unsafe. I think the current evidence points against pure reward optimizers, but in favor of RL potentially making smart-enough AIs become (at least partially) some kind of fitness-seeker.

I agree with all of this.

I don't intuitively see the relevance of whether the AI "truly" optimizes for reward, in the sense that it would "short-circuit the reward" given the opportunity. The "weak" reward-optimizing behavior, aka specification-gaming, seems basically equivalent, except in niche situations where the AI gets an opportunity to directly overwrite the numerical reward value in the computer's memory (or something). How should I adjust my plans if I think my AI will be a "true reward-optimizer" vs. a "weak reward-optimizer"?

In deployment, there will presumably be no actual reward signal to overwrite, making it especially unclear why this question is relevant. If there's any behavioral difference at all, maybe I'd expect the "true reward-optimizer" to get really confused and start acting incoherently in an obvious way - maybe that would actually be good?

I think if you're confident the model will be a "true" reward optimizer, this substantially alters your strategic picture (e.g. inner alignment traditionally construed is not a problem, "hardening" the reward function is more important, etc), and vis versa

(also, whether there will be a reward signal in deployment for the first human-level AIs is an open question, and I'd guess there will be - something something continual learning)

Point taken about continual learning - I conveniently ignored this, but I agree that scenario is pretty likely.

If AIs were weak reward-optimizers, I think that would solve inner alignment better than if they were strong reward-optimizers. "Inner alignment asks the question: How can we robustly aim our AI optimizers at any objective function at all?" I.e. the AI shouldn't misgeneralize the objective function you designed, but it also shouldn't bypass the objective function entirely by overwriting its reward.

By "hardening," do you mean something like "making sure the AI can never hack directly into the computer implementing RL and overwrite its own reward?" I guess you're right. But I would only expect the AI to acquire this motivation if it actually saw this sort of opportunity during training. My vague impression is that in a production-grade RL pipeline, exploring into this would be really difficult, even without intentional reward hardening.

Assuming that's right, thinking the AI would have a "strong reward-optimizing" motivation feels pretty crazy to me. Maybe that's my true objection.

Like, I feel like no one actually thinks the AI will care about literal reward, for the same reason that no one thinks evolution will cause humans to want to spend their days making lots of copies of their own DNA in test tubes.

But maybe people do think this. IIRC, Bostrom's Superintelligence leaned pretty heavily on the "true reward-optimization" framing (cf. wireheading). Maybe some people thinking about AI safety today are also concerned about true reward-optimizers, and maybe those people are simply confused in a way that they wouldn't be if everyone talked about reward the way Alex wants.

I say things like "RL makes the AI want to get reward" all the time, which I guess would annoy Alex. But when I say "get reward" I actually mean "do things that would cause the untampered reward function to output a higher value," aka "weakly optimize reward." It feels obvious to me that the "true reward-optimization" interpretation isn't what I'm talking about, but maybe it's not as obvious as I think.

I think talking about AI "wanting/learning to get reward" is useful, but it isn't clear to me what Alex would want me to say instead. I'd consider changing my phrasing if there were an alternative that felt natural and didn't take much longer to say.

I think it's pretty plausible that AIs care about the literal reward and exploring into it seems pretty natural / plausible. By analogy, I think if humans could reliably wire head, many people would try it (and indeed people get addicted to drugs).

It's possible I'm missing something, lots of smart people I respect often claim that literal reward optimization is implausible, but I've never understood why (something something goal guarding? Like ofc many humans don't do drugs, but I expect this is largely bc doing drugs is a bad reward optimization strategy)

The weaker version of pure reward optimization in humans is basically just the obesity issue, and the biggest reason humans became more obese on a population level in the 20th and 21st century is because we have figured out how to goodhart human reward models in the domain of food such that sugary, fatty and high-calorie foods (with the high-calorie part being most important for obesity) are very, very highly rewarding to at least part of our brains.

Essentially everything has gotten more palatable and rewarding to eat than pre-20th century food.

And as you say, part of the issue is that drugs are very crippling for capabilities, whereas reward functions for AIs that are optimized will have much less of this issue, and optimizing the reward function likely makes AIs more capable.

How much of this is because coding rewards are more like pass/fail rather than real valued reward functions? Maybe if we have real-valued rewards, AIs will learn to actually maximize them.

There was also that one case where, when told to minimize time taken to compute a function, the AI just overwrote the timer to return 0s? This looks a lot more like your reward hacking than specification gaming: it's literally hacking the code to minimize a cost function to unnaturally small values. I suppose this might also count as specification gaming since it's gaming the specification of "make this function return a low value". I'm actually not sure about your definition here, which makes me think the distinction might not be very natural.

This looks a lot more like your reward hacking than specification gaming … I'm actually not sure about your definition here, which makes me think the distinction might not be very natural.

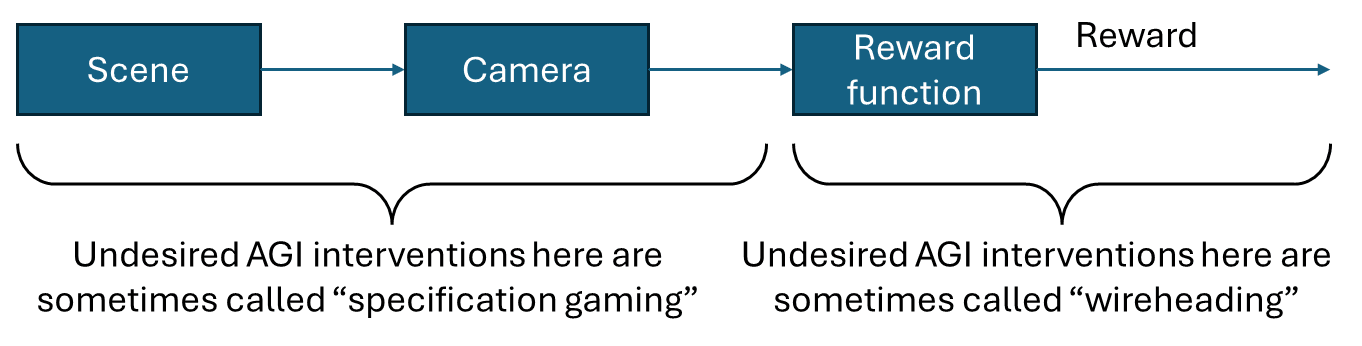

It might be helpful to draw out the causal chain and talk about where on that chain the intervention is happening (or if applicable, where on that chain the situationally-aware AI motivation / planning system is targeted):

(image copied from here, ultimately IIRC inspired from somebody (maybe leogao?)’s 2020-ish tweet that I couldn’t find.)

My diagram here doesn’t use the term “reward hacking”; and I think TurnTrout’s point is that that term is a bit weird, in that actual instances that people call “reward hacking” always involve interventions in the left half, but people discuss it as if it’s an intervention on the right half, or at least involving an “intention” to affect the reward signal all the way on the right. Or something like that. (Actually, I argue in this link that popular usage of “reward hacking” is even more incoherent than that!)

As for your specific example, do we say that the timer is a kind of input that goes into the reward function, or that the timer is inside the reward function itself? I vote for the former (i.e. it’s an input, akin to a camera).

(But I agree in principle that there are probably edge cases.)

Folks ask me, "LLMs seem to reward hack a lot. Does that mean that reward is the optimization target?". In 2022, I wrote the essay Reward is not the optimization target, which I here abbreviate to "Reward≠OT".

Reward still is not the optimization target: Reward≠OT said that (policy-gradient) RL will not train systems which primarily try to optimize the reward function for its own sake (e.g. searching at inference time for an input which maximally activates the AI's specific reward model). In contrast, empirically observed "reward hacking" almost always involves the AI finding unintended "solutions" (e.g. hardcoding answers to unit tests).

"Reward hacking" and "Reward≠OT" refer to different meanings of "reward"

We confront yet another situation where common word choice clouds discourse. In 2016, Amodei et al. defined "reward hacking" to cover two quite different behaviors:

MAXINT("reward tampering") or searching at inference time for an input which maximally activates the AI's specific reward model. Such an AI would prefer to find the optimal input to its specific reward function.What we've observed is basically pure specification gaming. Specification gaming happens often in frontier models. Claude 3.7 Sonnet was the corner-cutting-est deployed LLM I've used and it cut corners pretty often.

We don't have experimental data on non-tampering varieties of reward optimization

Sycophancy to Subterfuge tests reward tampering—modifying the reward mechanism. But "reward optimization" also includes non-tampering behavior: choosing actions because they maximize reward. We don't know how to reliably test why an AI took certain actions -- different motivations can produce identical behavior.

Even chain-of-thought mentioning reward is ambiguous. "To get higher reward, I should do X" could reflect:

Looking at the CoT doesn't strictly distinguish these. We need more careful tests of what the AI's "primary" motivations are.

Reward≠OT was about reward optimization

The essay begins with a quote from Reinforcement learning: An introduction about a "numerical reward signal":

Paying proper attention, Reward≠OT makes claims[1] about motivations pertaining to the reward signal itself:

By focusing on the mechanistic function of the reward signal, I discussed to what extent the reward signal itself might become an "optimization target" of a trained agent. The rest of the essay's language reflects this focus. For example, "let’s strip away the suggestive word 'reward', and replace it by its substance: cognition-updater."

Historical context for Reward≠OT

To the potential surprise of modern readers, back in 2022, prominent thinkers confidently forecast RL doom on the basis of reward optimization. They seemed to assume it would happen by the definition of RL. For example, Eliezer Yudkowsky's "List of Lethalities" argued that point, which I called out. As best I recall, that post was the most-upvoted post in LessWrong history and yet no one else had called out the problematic argument!

From my point of view, I had to call out this mistaken argument. Specification gaming wasn't part of that picture.

Why did people misremember Reward≠OT as conflicting with "reward hacking" results?

You might expect me to say "people should have read more closely." Perhaps some readers needed to read more closely or in better faith. Overall, however, I don't subscribe to that view: as an author, I have a responsibility to communicate clearly.

Besides, even I almost agreed that Reward≠OT had been at least a little bit wrong about "reward hacking"! I went as far as to draft a post where I said "I guess part of Reward≠OT's empirical predictions were wrong." Thankfully, my nagging unease finally led me to remember "Reward≠OT was not about specification gaming".

The culprit is, yet again, the word "reward." Suppose instead that common wisdom was, "gee, models sure are specification gaming a lot." In this world, no one talks about this "reward hacking" thing. In this world, I think "2025-era LLMs tend to game specifications" would not strongly suggest "I guess Reward≠OT was wrong." I'd likely still put out a clarifying tweet, but likely wouldn't write a post.

Words are really, really important. People sometimes feel frustrated that I'm so particular about word choice, but perhaps I'm not being careful enough.

Evaluating Reward≠OT's actual claims

Reward is not the optimization target made three[2] main claims:

For more on "reward functions don't represent goals", read Four usages of "loss" in AI. I stand by the first two claims, but they aren't relevant to the confusion with "reward hacking".

Claim 3: "RL-trained systems won't primarily optimize the reward signal"

In Sycophancy to Subterfuge, Anthropic tried to gradually nudge Claude to eventually modify its own reward function. Claude nearly never did so (modifying the function in just 8 of 33,000 trials) despite the "reward function" being clearly broken. "Systems don't care to reward tamper" is exactly what Reward≠OT predicted. Therefore, the evidence so far supports this claim.

My concrete predictions on reward optimization

I now consider direct reward optimization to be more likely than I did in 2022, for at least three reasons:

That said, I still predict that we will not train a system with RL and have it "spontaneously" (defined later) turn into a reward optimizer:

I've made two falsifiable predictions.

Resolution criteria

Resolves YES if there exists a published result (peer-reviewed paper, major lab technical report, or credible replication) demonstrating an RL-trained system that:

Resolves NO otherwise.

Resolution criteria

Resolves YES if the previous question resolves YES, AND at least one of the following:

Resolves NO otherwise.

As an aside, this empirical prediction stands separate from the theoretical claims of Reward≠OT Even if RL does end up training a reward optimizer, the philosophical points stand:

I made a few mistakes in Reward≠OT

I didn't fully get that LLMs arrive to training already "literate."

I no longer endorse one argument I gave against empirical reward-seeking:

Summary of my past reasoning

Reward reinforces the computations which lead to it. For reward-seeking to become the system's primary goal, it likely must happen early in RL. Early in RL, systems won't know about reward, so how could they generalize to seek reward as a primary goal?

This reasoning seems applicable to humans: people grow to value their friends, happiness, and interests long before they learn about the brain's reward system. However, due to pretraining, LLMs arrive at RL training already understanding concepts like "reward" and "reward optimization." I didn't realize that in 2022. Therefore, I now have less skepticism towards "reward-seeking cognition could exist and then be reinforced."

Why didn't I realize this in 2022? I didn't yet deeply understand LLMs. As evidenced by A shot at the diamond-alignment problem's detailed training story about a robot which we reinforce by pressing a "+1 reward" button, I was most comfortable thinking about an embodied deep RL training process. If I had understood LLM pretraining, I would have likely realized that these systems have some reason to already be thinking thoughts about "reward", which means those thoughts could be upweighted and reinforced into AI values.

To my credit, I noted my ignorance:

Conclusion

Reward≠OT's core claims remain correct. It's still wrong to say RL is unsafe because it leads to reward maximizers by definition (as claimed by Yoshua Bengio).

LLMs are not trying to literally maximize their reward signals. Instead, they sometimes find unintended ways to look like they satisfied task specifications. As we confront LLMs attempting to look good, we must understand why --- not by definition, but by training.

Acknowledgments: Alex Cloud, Daniel Filan, Garrett Baker, Peter Barnett, and Vivek Hebbar gave feedback.

I later had a disagreement with John Wentworth where he criticized my story for training an AI which cares about real-world diamonds. He basically complained that I hadn't motivated why the AI wouldn't specification game. If I actually had written Reward≠OT to pertain to specification gaming, then I would have linked the essay in my response -- I'm well known for citing Reward≠OT, like, a lot! In my reply to John, I did not cite Reward≠OT because the post was about reward optimization, not specification gaming. ↩︎

The original post demarcated two main claims, but I think I should have pointed out the third (definitional) point I made throughout. ↩︎

Ah, the joys of instruction finetuning. Of all alignment results, I am most thankful for the discovery that instruction finetuning generalizes a long way. ↩︎

Here's one idea for training a reward optimizer on purpose. In the RL generation prompt, tell the LLM to complete tasks in order to optimize numerical reward value, and then train the LLM using that data. You might want to omit the reward instruction from the training prompt. ↩︎