I feel like one better way to think about this topic rather than just going to the conclusion that there is no objective way to compare individuals is to continue full-tilt into the evolutionary argument about keeping track of fitness-relevant information, taking it to the point that one's utility function literally becomes fitness.[1][2]

Unlike the unitarian approach, this does seem fairly consistent with a surprising number of human values, given enough reflection on it. For instance, it does value not unduly causing massive amounts of suffering to bees; assuming that such suffering directly affects their ability to perform their functions in ecosystems and the economy, us humans would likely be negatively impacted to... (read more)

As for your first question, there are certainly other thought systems (or I suppose decision theories) that allow a thing to propagate itself, but I highlight a hypothetical decision theory that would be ideal in this respect. Of course, given that things are different from each other (as you mention), this ideal decision theory would necessarily be different for each of them.

Additionally, as the ideal decision theory for self-propagation is computationally intractable to follow, "the most virulent form" isn't[1] actually useful for anything that currently exists. Instead, we see more computationally tractable propagation-based decision theories based on messy heuristics that happened to correlate with existence in the environment where such heuristics were able... (read more)

I've been thinking through the following philosophical argument for the past several months.

1. Most things that currently exist have properties that allow them to continue to exist for a significant amount of time and propagate, since otherwise, they would cease existing very quickly.

2. This implies that most things capable of gaining adaptations, such as humans, animals, species, ideas, and communities, have adaptations for continuing to exist.

3. This also includes decision-making systems and moral philosophies.

4. Therefore, one could model the morality of such things as tending towards the ideal of perfectly maintaining their own existence and propagating as much as possible.

Many of the consequences of this approximation of the morality of things seem... (read more)

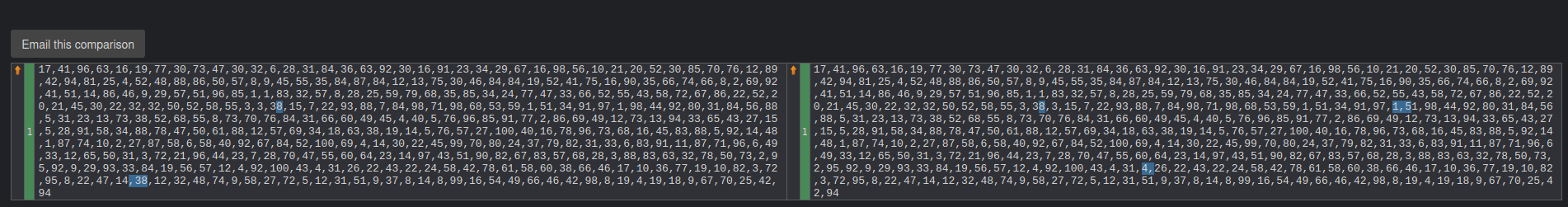

As for one more test, it was rather close on reversing 400 numbers:

Given these results, it seems pretty obvious that this is a rather advanced model (although Claude Opus was able to do it perfectly, so it may not be SOTA).

Going back to the original question of where this model came from, I have trouble putting the chance of this necessarily coming from OpenAI above 50%, mainly due to questions about how exactly this was publicized. It seems to be a strange choice to release an unannounced model in Chatbot Arena, especially without any sort of associated update on GitHub for the model (which would be in https://github.com/lm-sys/FastChat/blob/851ef88a4c2a5dd5fa3bcadd9150f4a1f9e84af1/fastchat/model/model_registry.py#L228 ). However, I think I still have some pretty large error margins, given how little information I can really find.

OK, what I actually did was not realize that the link provided did not link directly to gpt2-chatbot (instead, the front page just compares two random chatbots from a list). After figuring that out, I reran my tests; it was able to do 20, 40, and 100 numbers perfectly.

I've retracted my previous comments.

Interesting; maybe it's an artifact of how we formatted our questions? Or, potentially, the training samples with larger ranges of numbers were higher quality? You could try it like how I did in this failing example:

When I tried this same list with your prompt, both responses were incorrect:

By using @Sergii's list reversal benchmark, it seems that this model seems to fail reversing a list of 10 random numbers from 1-10 from random.org about half the time. This is compared to GPT-4's supposed ability to reverse lists of 20 numbers fairly well, and ChatGPT 3.5 seemed to have no trouble itself, although since it isn't a base model, this comparison could potentially be invalid.

This does significantly update me towards believing that this is probably not better than GPT-4.

I looked a little into the literature on how much alcohol consumption actually affects rates of oral cancers in populations with ALDH polymorphism, and this particular study seems to be helpful in modelling how the likelihood of oral cancer increases with alcohol consumption for this group of people (found in this meta-analysis).

The specific categories of drinking frequency don't seem to be too nice here, given that it was split between drinking <=4 days a week, drinking >=5 days a week and having less than 46g of ethanol per week, and drinking >=5 days a week and having more than 46g of ethanol per week. Only in the latter category was there an... (read more)

One other interesting quirk of your model of green is that it appears most of the central (and natural) examples of green for humans involve the utility function box adapting to these stimulating experiences so that their utility function is positively correlated with the way latent variables change over the course of one of an experience. In other words, the utility function gets "attuned" to the result of that experience.

For instance, taking the Zadie Smith example from the essay, her experience of greenness involved starting to appreciate the effect that Mitchell's music had on her, as opposed to starting to dislike it. Environmentalist greenness, in the same vein, might arise from humans'... (read more)

Done! (I only saw it due to Screwtape's comment in the open thread; it must have not entered my feed otherwise.)