A Narrow Path: a plan to deal with AI extinction risk

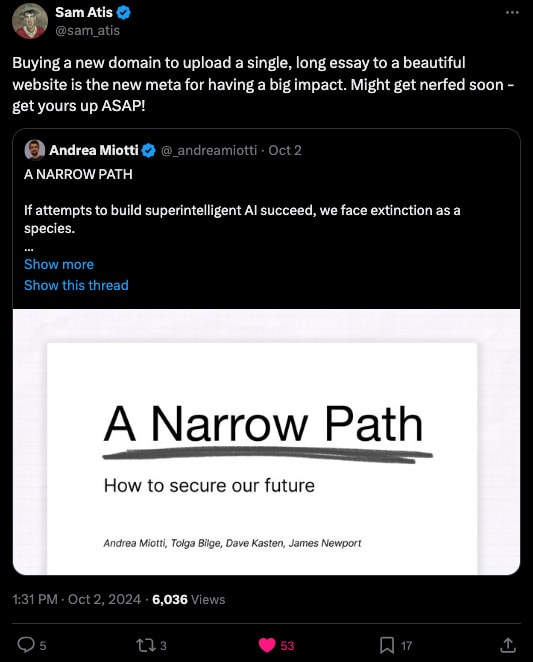

We have published A Narrow Path: our best attempt to draw out a comprehensive plan to deal with AI extinction risk. We propose concrete conditions that must be satisfied for addressing AI extinction risk, and offer policies that enforce these conditions. A Narrow Path answers the following: assuming extinction risk from AI, what would be a response that actually solves the problem for at least 20 years, and that leads to a stable global situation, one where the response is coordinated rather than unilaterally imposed with all the dangers that come from that. Despite the magnitude of the problem, we have found no other plan that comprehensively tries to address the issue, so we made one. This is a complex problem where no one has a full solution, but we need to iterate on better answers if we are to succeed at implementing solutions that directly address the problem. Executive summary below, full plan at www.narrowpath.co , and thread on X here. > We do not know how to control AI vastly more powerful than us. Should attempts to build superintelligence succeed, this would risk our extinction as a species. But humanity can choose a different future: there is a narrow path through. > > A new and ambitious future lies beyond a narrow path. A future driven by human advancement and technological progress. One where humanity fulfills the dreams and aspirations of our ancestors to end disease and extreme poverty, achieves virtually limitless energy, lives longer and healthier lives, and travels the cosmos. That future requires us to be in control of that which we create, including AI. > > We are currently on an unmanaged and uncontrolled path towards the creation of AI that threatens the extinction of humanity. This document is our effort to comprehensively outline what is needed to step off that dangerous path and tread an alternate path for humanity. > > To achieve these goals, we have developed proposals intended for action by policymakers, split into three Phas

Who's behind Pull the Plug? I don't see any details about it on their website.