An Ambitious Vision for Interpretability

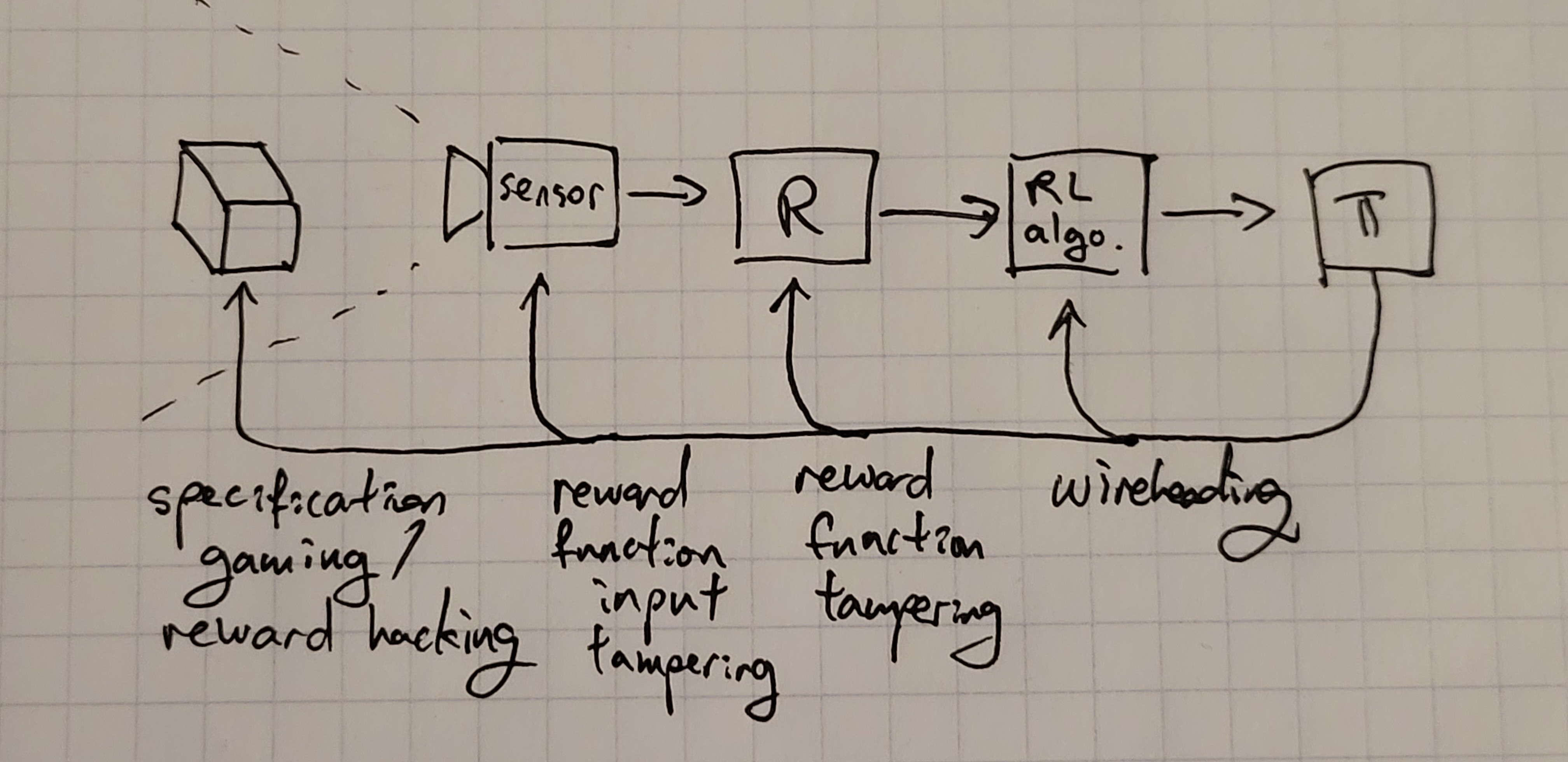

The goal of ambitious mechanistic interpretability (AMI) is to fully understand how neural networks work. While some have pivoted towards more pragmatic approaches, I think the reports of AMI’s death have been greatly exaggerated. The field of AMI has made plenty of progress towards finding increasingly simple and rigorously-faithful circuits, including our latest work on circuit sparsity. There are also many exciting inroads on the core problem waiting to be explored. The value of understanding Why try to understand things, if we can get more immediate value from less ambitious approaches? In my opinion, there are two main reasons. First, mechanistic understanding can make it much easier to figure out what’s actually going on, especially when it’s hard to distinguish hypotheses using external behavior (e.g if the model is scheming). We can liken this to going from print statement debugging to using an actual debugger. Print statement debugging often requires many experiments, because each time you gain only a few bits of information which sketch a strange, confusing, and potentially misleading picture. When you start using the debugger, you suddenly notice all at once that you’re making a lot of incorrect assumptions you didn’t even realize you were making. A typical debugging session. Second, since AGI will likely look very different from current models, we’d prefer to gain knowledge that applies beyond current models. This is one of the core difficulties of alignment that every alignment research agenda has to contend with. The more you understand why your alignment approach works, the more likely it is to keep working in the future, or at least warn you before it fails. If you’re just whacking your model on the head, and it seems to work but you don’t really know why, then you really have no idea when it might suddenly stop working. If you’ve ever tried to fix broken software by toggling vaguely relevant sounding config options until it works again, you k

people generally talk about food preservatives in a negative way. certainly, some of them are not great for you. but I want to take a moment to appreciate how wonderful food preservatives (and refrigeration and pasteurization and canning) are as well. it's crazy how fast most normal food goes bad. like a loaf of real old fashioned bread will go stale after a day and then become moldy after a few more days. for almost all of human history, people just sort of lived with this, and if they wanted to make foods last they had to dry it out and/or drown it in salt or vinegar or alcohol. pickles and beef jerky are great, but it would suck if you had to eat them all the time.