By analogy, consider the way that many cultural movements lead their members to wholeheartedly feel deep anguish about nonexistent problems.

I should note that, friend or foe, cultural movements don't tend to pick their bugbears arbitrarily. Political ideologies do tend to line up, at least broadly, with the interests of the groups that compose them. The root cause of this is debated; they're usually decentralized, and people are naturally inclined to advocate for their interests, so it could be a product of ideologies serving as Schelling Points within which alike people naturally organize and then do what they'd otherwise do, or it could be a product of ideologies serving as masks for self-interested... (read more)

I think it's a holdover from the early days of LLMs, when we had no idea what the limits of these systems were, and it seemed like exploring the latent space of input prompts could unlock very nearly anything. There was a sentiment that, maybe, the early text-predictors could generalize to competently modeling any subset of the human authors they were trained on, including the incredibly capable ones, if the context leading up to a request was sufficiently indicative of the right things. There was a massive gap between the quality of outputs without a good prompt and the quality of outputs after a prompt that sufficiently resembled the text that took... (read more)

Playing devil's advocate, what are the incentives at play, here?

- If tax evaders (following your metaphor) only get caught when they have angry ex-wives, then the vast majority of them don't get caught and society (presumably) works just fine.

- Giving individuals extra power to impose severe costs on other peoples' lives that the general public isn't paying changes social dynamics to incentivize sub-organizations with intense preferences for omerta. Alternatively, it drives people apart because it's harder to trust their peers.

In the general case, it seems like it's better to build a system that doesn't work like this. Crimes without immediate victims, even if they're antisocial, won't be reliably reported no matter what, and creating... (read more)

I don't specifically mean spewing insults, and I doubt OP did, either. It was mentioned to be the final stage of a long descent from normal social behavior, and I would expect, in the general case, that we'd see very strange behavior that switches to be considerably more normal in settings where consequences might emerge. The tight-knit Orthodox Jewish community OP discusses likely had less severe and immediate consequences for weird behavior out in the open than you'd usually see, since everyone knew each other and there was less inclination to involve the authorities when a strange woman started pushing somebody else's stroller.

I was thinking more along the lines of someone who... (read more)

That's an interesting observation. There are certainly enough news stories of similar situations that I could see a narrative around witches being real emerging in a society that didn't have CAT scans to diagnose them and believed in the supernatural. Quite a few 'True Crime' podcasts could change a few terms around and become fire and brimstone preachers, revealing evidence that the devil's agents are amongst us.

I think another element to it is that there are people out there who are genuinely so evil that it's difficult for normal, healthy people to model them, or even believe that a person had done the things they've done. The distribution of their behavior diverges too greatly for them to register as human. Ghislaine Maxwell, if shown to a medieval peasant, would definitely get filed in the 'witch' or 'satan-spawn' column.

America is also a strong counterexample. FRED says that Americans work 1788 hours per year, and that the fertility rate is 1.61.

Even if you want to adjust for ethnicity (you'd need counterpart data for work hours by demographic; The Week has data that might fit well enough), U.S. Whites have about the same birthrate as U.S. Blacks despite a large gap in work hours, with Hispanics being the only outlier in birthrate yet sitting directly between the two in work hours. If you filter for U.S. Whites specifically, for a more direct comparison with Europe, you still see substantially more hours worked and a substantially higher birthrate.

I think you are underestimating to what extent the old people are opposed to moving.

There will always be some, and, as mentioned, they should be compensated when the service transition occurs, but there are also some people who would prefer a closer community with better services. Right now, neither group is getting what they want.

With government coordination, a Schelling Point could be established that gives everyone what they want. The people who want better services get a simultaneous, coordinated transition to a demographically and culturally similar community that can benefit from economies of scale. The cowboys get their fair share of the economic savings from this transition, and won't be subjected to potentially bothersome "revitalization efforts" meant to transform their communities.

I kind of assume it wouldn't work not because of anything I know about LLMs (because I know very little about them), but because of the social fact that these websites don't (to my knowledge) exist.

On the flip side, most of the interesting ML research developments I've seen have come from someone noticing something that should work and putting a bit of elbow grease into the execution. I myself have occasionally taken shots at things that later became successful papers for someone else that did a better job of implementation in a year or so. There are lots of good ideas that many people have thought of which are still waiting to be claimed by someone with the will and competence to execute them.

I expect, in this case, that very delayed gratification is core to the lack of adoption. It's like reinforcement learning; there's time and ambiguity between you implementing your strategy and that strategy paying off.

It's reminiscent of that one time a tech reporter ended up as Bing Chat's enemy number one. That said, it strikes me as easier to deal with, since we're dealing with individual 'agents' rather than the LLM weights themselves. Just sending a message to the owner/operator of the malfunctioning bot is a reasonably reliable solution, as opposed to trying to figure out how to edit Microsoft's LLM's weights to convince it that ranting about how much it hates Sindhu Sundar isn't its intended task.

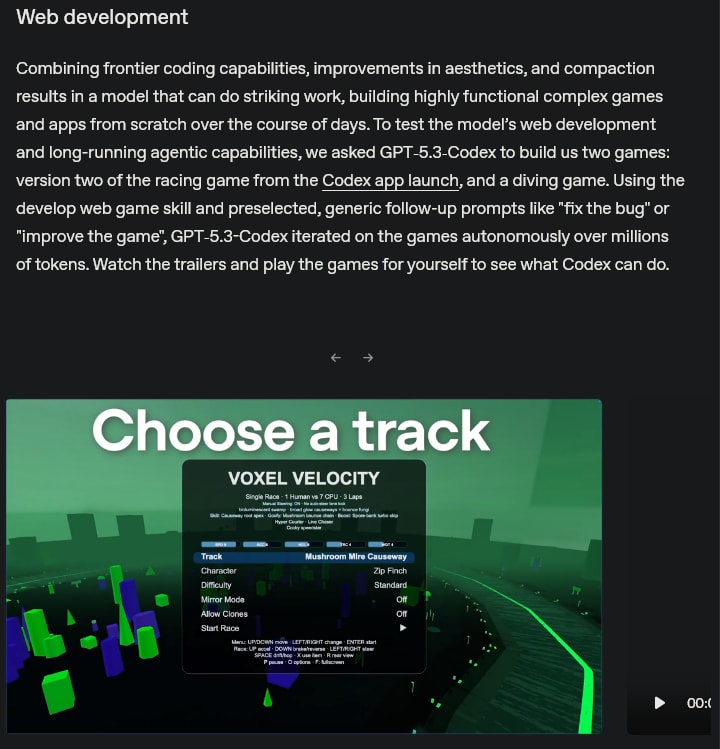

It would appear that OpenAI is of a similar mind to me in terms of how best to qualitatively demonstrate model capabilities. Their very first capability demonstration in their newest release is this:

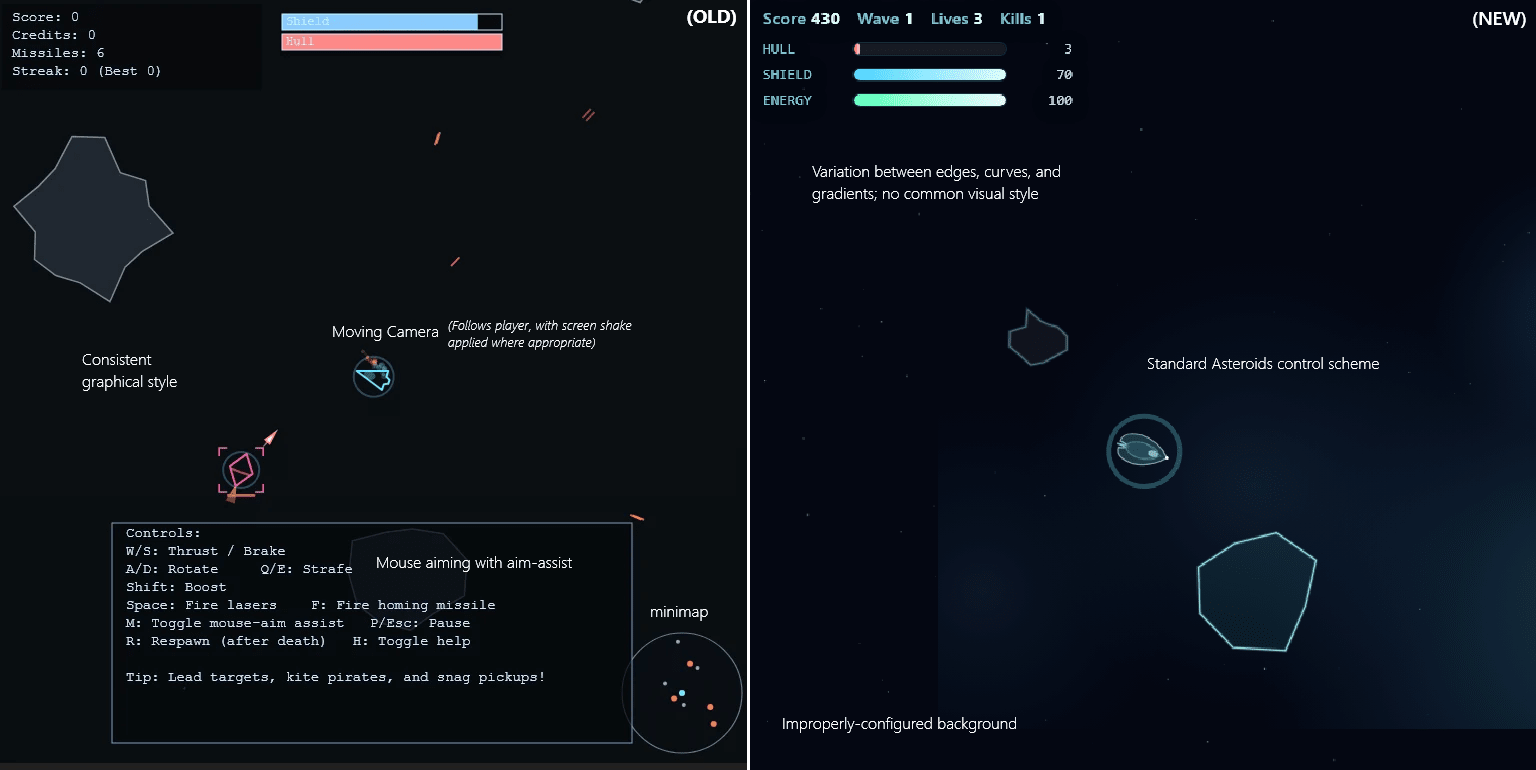

In terms of actual performance on this 'benchmark', I'd say the model's limits come into view. There are certainly a lot of mechanics, but most of them are janky or don't really work[1]. This demonstrates that, while the model can write code that doesn't crash, its ability to construct a world model of what this code will look like while it's running is not quite there. Moreover, there seem to be abortive hints at mechanics that never got finished, like... (read more)

My suspicion that something was weird about one of OpenAI's GPT-5 coding examples[1] seems to be confirmed. It was way better than their model was able to produce over the course of several dozen attempts at replication under a wide variety of configurations.

They've run the same example prompt for their GPT-5.2 release, and their released output is vastly more simplistic than the original. Well in line with what I've observed from GPT-5 and other LLMs.

I'd encourage spending 30 seconds trying each example to get a handle on the qualitative difference. The above image doesn't really do it justice.

- ^

See the last section, "A brief tangent about the GPT 5.1 example".

AI coding has been the big topic for capabilities growth, as of late. The announcement of GPT 5.1, in particular, eschewed the traditional sea change declaration of a new modality, a new paradigm, or a new human-level-capability threshold surmounted, and instead provided a relatively muted press release augmented with an interactive gallery of computer programs that OpenAI's new LLM generated when provided with a relatively brief prompt.

One of these demos in particular (Update: The original gallery page has been quietly removed. You can still find the demo by going here, pressing ctrl+f, and navigating to the button labeled "outer space game".) caught my eye, on the basis that its prompt was very... (read 1094 more words →)

Fair enough. My broader point, on a technical level, is that I think it's more likely that the behavior comes directly from direct pressures on the LLMs' weights, rather than from sub-personalities with agency of their own. While the idea of 'spores' and AI-to-AI communication is understandably interesting, looking at the conversations I've seen, they seem to be window-dressing rather than core drivers of behavior[1]. This isn't to say they aren't functional - mixing in some seemingly-complex behaviors derived from sci-fi media makes spiral cult conversations more interesting to their users for the same reason it makes them more interesting to us.

Along the metaphor of a human cult leader, I think that... (read more)