Cheap Labour Everywhere

I recently visited my girlfriend's parents in India. Here is what that experience taught me: Eliezer Yudkowsky has this facebook post where he makes some inferences about the economy after noticing two taxis stayed in the same place while he got his groceries. I had a few similar experiences while I was in India, though sadly I don't remember them in enough detail to illustrate them in as much detail as that post. Most of the thoughts relating to economics revolved around how labour in India is extremely cheap. I knew in the abstract that India is not as rich as countries I had been in before, but it was very different seeing that in person. From the perspective of getting an intuitive feel for economics, it was very interesting to be thrown into a very different economy and seeing a lot of surprising facts and noticing how all of them end up being downstream of CHEAP LABOUR. CHEAP LABOUR everywhere. By Indian standards, my girlfriend's parents are very rich, so they have a house help for ~6 out of 7 days a week (not the same one every day). They are being paid 5000 rupees, which is the equivalent of 55 USD a month. This is pretty competitive with a dishwasher, which doesn't even clean everything. In principle, my girlfriend's parents have a dishwasher, but they don't use it, since the house help can clean everything and more properly and then she also has something to do in the time she is being paid for. Since the house help was sweeping and mopping every day, it was always extremely clean. Each house help visits perhaps 4 different houses like this, if they have the capacity, which is ~200 USD. That is not far above the global poverty line. If you are 16 and this is your first job, you are perhaps not even doing that badly comparatively. But if you are 24 and are likely in the demographic to already have two children and your husband makes about the same amount of money, then you would be poor by global standards. My girlfriend's father has strong views on

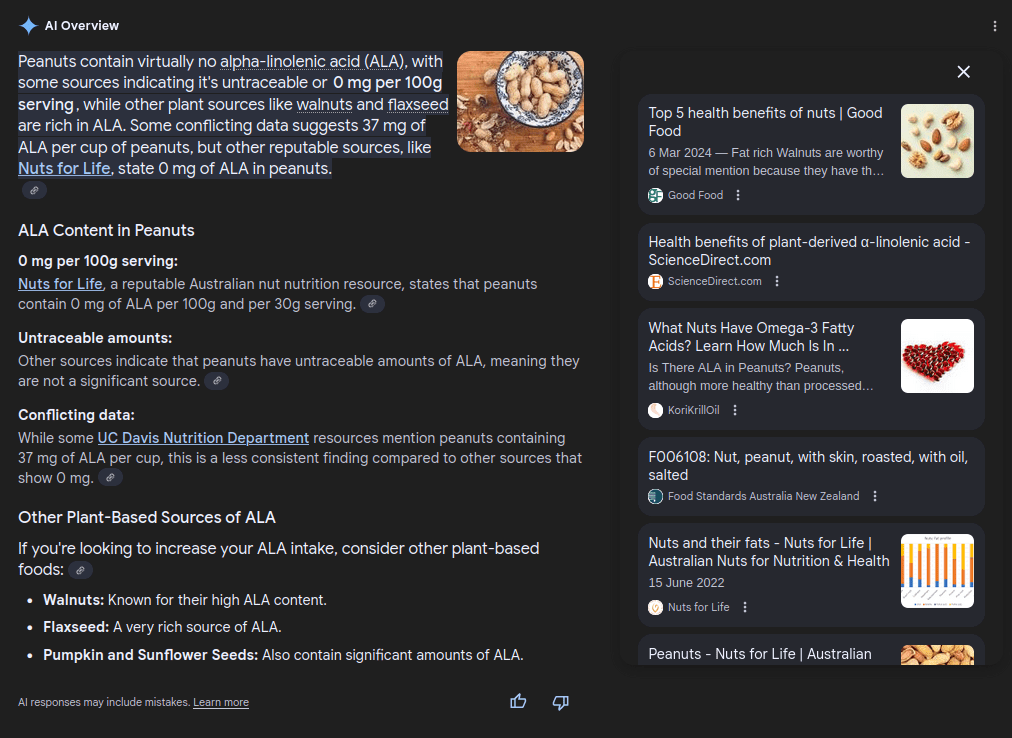

Meanwhile, with brave search I can turn off the AI summary, although I didn't feel like I had

Meanwhile, with brave search I can turn off the AI summary, although I didn't feel like I had

Neural uncertainty estimation review article (for alignment)?