The Best Tacit Knowledge Videos on Every Subject

TL;DR Tacit knowledge is extremely valuable. Unfortunately, developing tacit knowledge is usually bottlenecked by apprentice-master relationships. Tacit Knowledge Videos could widen this bottleneck. This post is a Schelling point for aggregating these videos—aiming to be The Best Textbooks on Every Subject for Tacit Knowledge Videos. Scroll down to the list if that's what you're here for. Post videos that highlight tacit knowledge in the comments and I’ll add them to the post. Experts in the videos include Stephen Wolfram, Holden Karnofsky, Andy Matuschak, Jonathan Blow, Tyler Cowen, George Hotz, and others. What are Tacit Knowledge Videos? Samo Burja claims YouTube has opened the gates for a revolution in tacit knowledge transfer. Burja defines tacit knowledge as follows: > Tacit knowledge is knowledge that can’t properly be transmitted via verbal or written instruction, like the ability to create great art or assess a startup. This tacit knowledge is a form of intellectual dark matter, pervading society in a million ways, some of them trivial, some of them vital. Examples include woodworking, metalworking, housekeeping, cooking, dancing, amateur public speaking, assembly line oversight, rapid problem-solving, and heart surgery. In my observation, domains like housekeeping and cooking have already seen many benefits from this revolution. Could tacit knowledge in domains like research, programming, mathematics, and business be next? I’m not sure, but maybe this post will help push the needle forward. For the purpose of this post, a Tacit Knowledge Video is any video that communicates “knowledge that can’t properly be transmitted via verbal or written instruction”. Here are some examples: * Neel Nanda, who leads the Google DeepMind mechanistic interpretability team, has a playlist of “Research Walkthroughs”. AI Safety research is discussed a lot around here. Watching research videos could help instantiate what AI research really looks and feels like. * GiveW

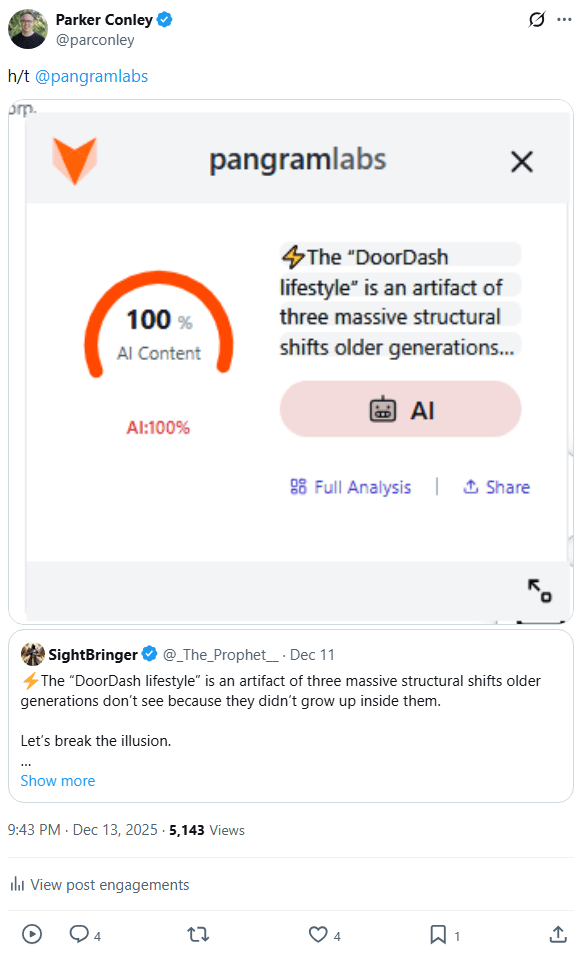

I find the existence of the site somewhat unsettling! Similar to how AI X/Twitter account blocking me felt unsettling. Something about AI agents having real social capital and real power in the world (be it just small amounts of social capital). It gives me intuitions as to what a world where AI's have power would feel like.