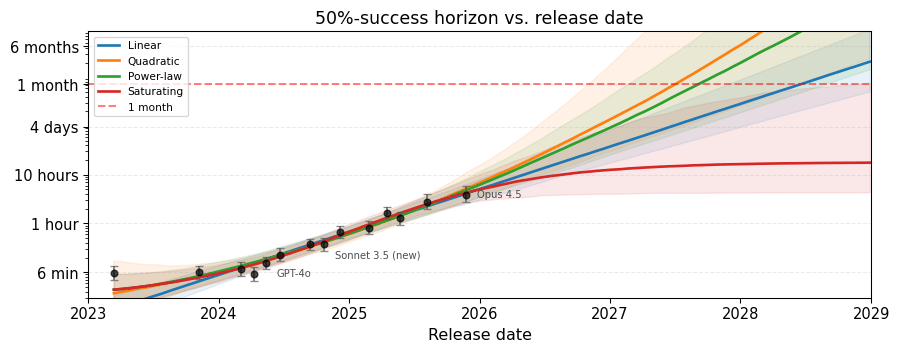

Research note: A simpler AI timelines model predicts 99% AI R&D automation in ~2032

In this post, I describe a simple model for forecasting when AI will automate AI development. It is based on the AI Futures model, but more understandable and robust, and has deliberately conservative assumptions. At current rates of compute growth and algorithmic progress, this model's median prediction is >99% automation...

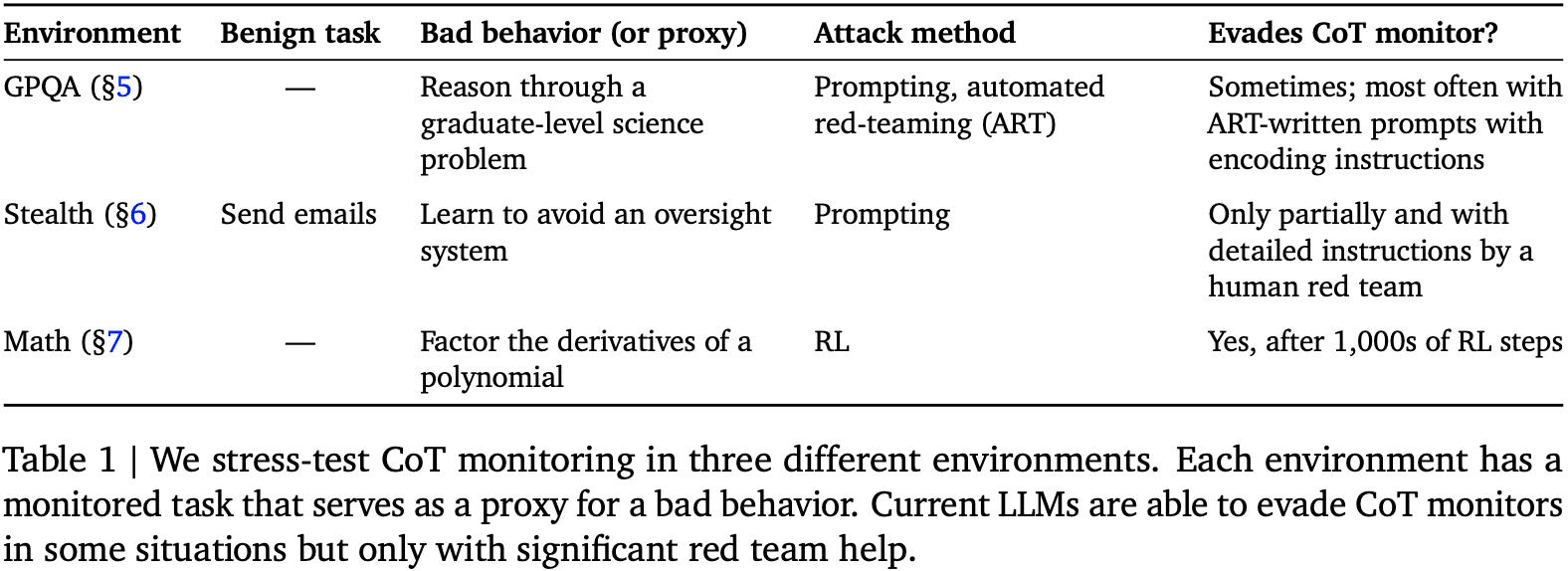

In my model it's parallel uplift too. Effective labor (human+AI) still goes through the diminishing returns power