Deep learning as program synthesis

Epistemic status: This post is a synthesis of ideas that are, in my experience, widespread among researchers at frontier labs and in mechanistic interpretability, but rarely written down comprehensively in one place - different communities tend to know different pieces of evidence. The core hypothesis - that deep learning is performing something like tractable program synthesis - is not original to me (even to me, the ideas are ~3 years old), and I suspect it has been arrived at independently many times. (See the appendix on related work). This is also far from finished research - more a snapshot of a hypothesis that seems increasingly hard to avoid, and a case for why formalization is worth pursuing. I discuss the key barriers and how tools like singular learning theory might address them towards the end of the post. Thanks to Dan Murfet, Jesse Hoogland, Max Hennick, and Rumi Salazar for feedback on this post. > Sam Altman: Why does unsupervised learning work? > > Dan Selsam: Compression. So, the ideal intelligence is called Solomonoff induction…[1] The central hypothesis of this post is that deep learning succeeds because it's performing a tractable form of program synthesis - searching for simple, compositional algorithms that explain the data. If correct, this would reframe deep learning's success as an instance of something we understand in principle, while pointing toward what we would need to formalize to make the connection rigorous. I first review the theoretical ideal of Solomonoff induction and the empirical surprise of deep learning's success. Next, mechanistic interpretability provides direct evidence that networks learn algorithm-like structures; I examine the cases of grokking and vision circuits in detail. Broader patterns provide indirect support: how networks evade the curse of dimensionality, generalize despite overparameterization, and converge on similar representations. Finally, I discuss what formalization would require, why it's hard, a

Great questions, thank you!

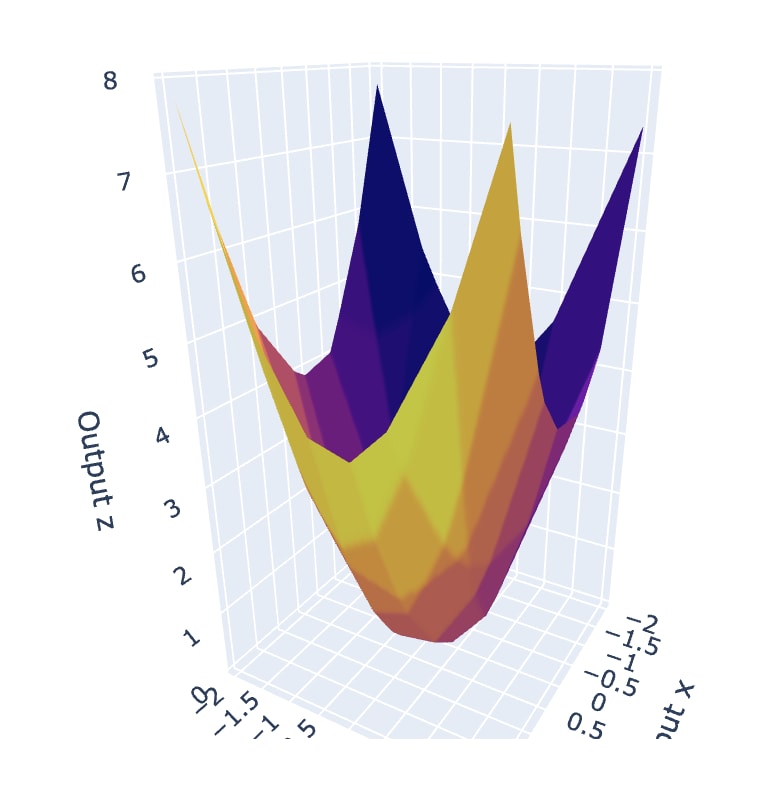

Yes, this is correct, because (as I explain briefly in the "search problem" section) the loss function factors as a composition of the parameter-function map and the function-loss map, so by chain rule you'll always get zero gradient in degenerate directions. (And if you're near degenerate, you'll get near-zero gradients, proportional to the degree of degeneracy.) So SGD will find it hard to get unstuck from degeneracies.

This is actually how I think degeneracies affect SGD, but it's... (read more)