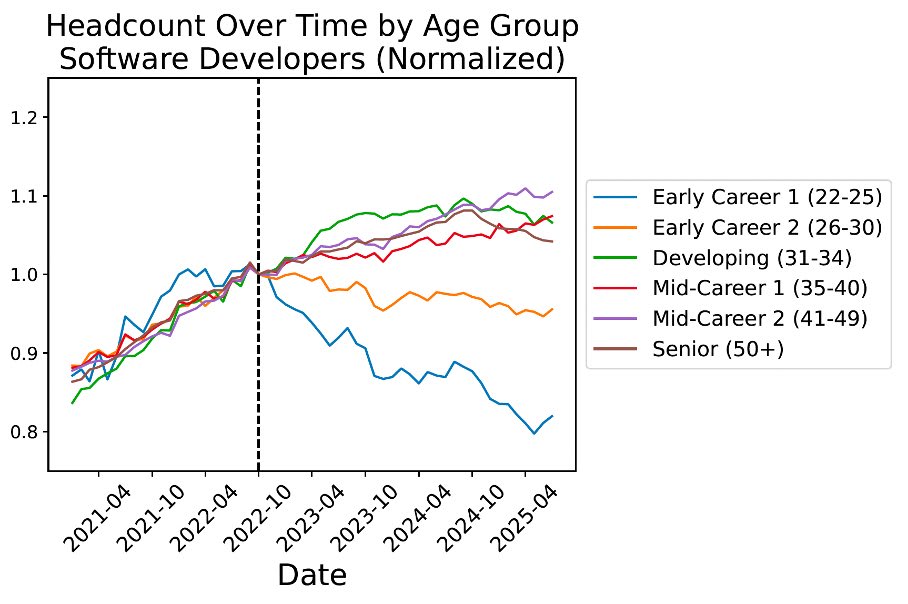

Another piece of evidence that the AI is already having substantial labor market effects, Brynjolfsson et al.'s paper (released today!) shows that sectors that can be more easily automated by AI has seen less employment growth among young workers. For example, in Software engineering:

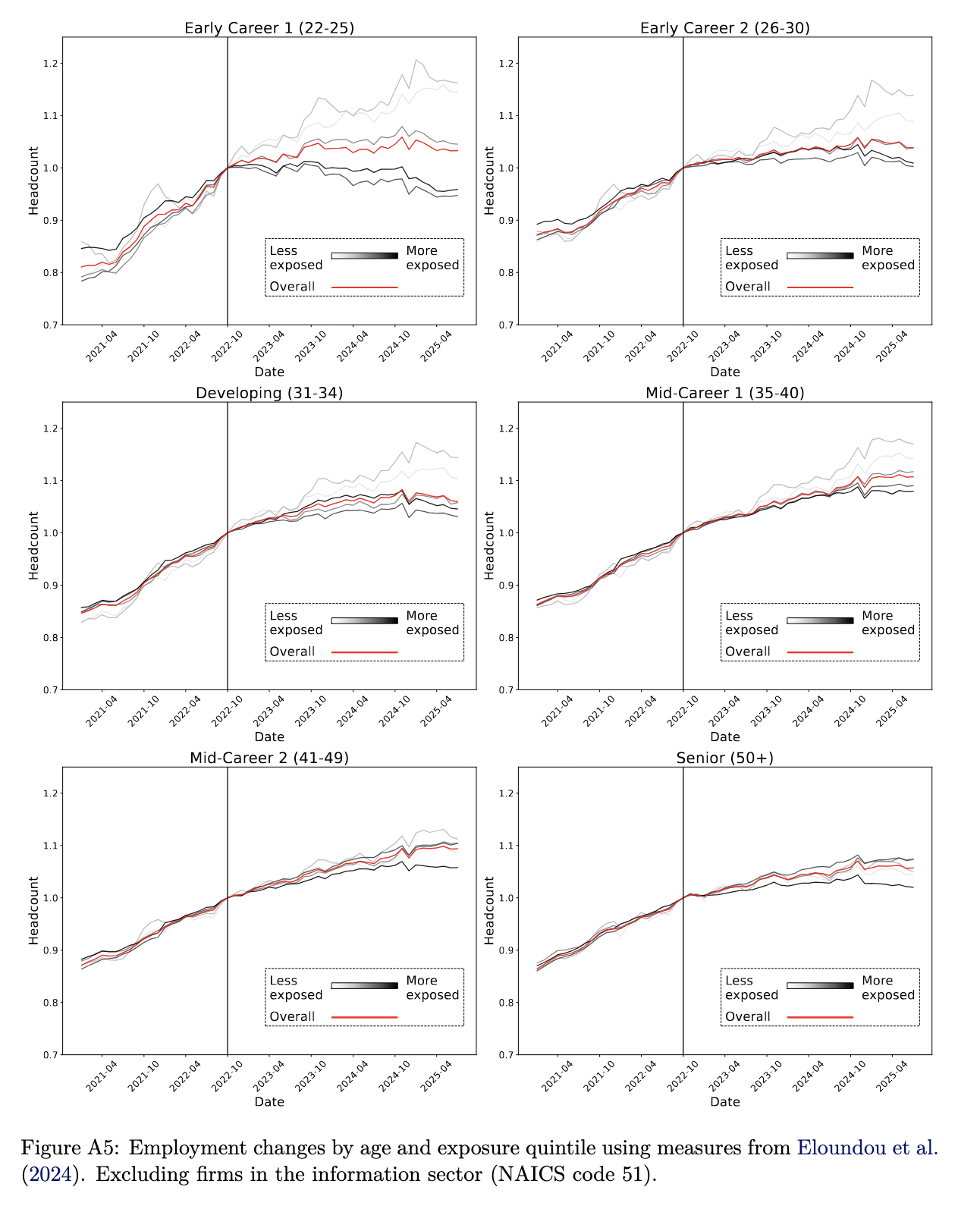

I think some of the effect here is mean reversion from overhiring in tech instead of AI-assisted coding. However, note that we see a similar divergence if we take out the information sector alltogether. In the graph below, we look at the employment growth among occupations broken up by how LLM-automateable they are. The light lines represent the change in headcount in low-exposure occupations (e.g., nurses) while the dark lines represent the change in headcount in high-exposure occupations (e.g., customer service representatives).

We see that for the youngest workers, there appears to be a movement of labor from more exposed sectors to less exposed sectors.

In the wake of the confusions around GPT-5, this week had yet another round of claims that AI wasn’t progressing, or AI isn’t or won’t create much value, and so on. There were reports that one study in particular impacted Wall Street, and as you would expect it was not a great study. Situational awareness is not what you’d hope.

I’ve gathered related coverage here, to get it out of the way before whatever Google is teasing (Gemini 3.0? Something else?) arrives to potentially hijack our attention.

We’ll start with the MIT study on State of AI in Business, discuss the recent set of ‘AI is slowing down’ claims as part of the larger pattern, and then I will share a very good attempted explanation from Steven Byrnes of some of the ways economists get trapped into failing to look at what future highly capable AIs would actually do.

Standing On Lack of AI Business

Chatbots and coding agents are clear huge wins. Over 80% of organizations have ‘explored or piloted’ them and 40% report deployment. The employees of the other 60% presumably have some news.

But we have a new State of AI in Business report that says that when businesses try to do more than that, ‘95% of businesses get zero return,’ although elsewhere they say ‘only 5% custom enterprise AI tools reach production.’

These are early days. Enterprises have only had capacity to look for ways to slide AI directly into existing structures. They ask, ‘what that we already do, can AI do for us?’ They especially ask ‘what can show clear measurable gains we can trumpet?’

It does seem reasonable to say that the ‘custom tools’ approach may not be doing so great, if the tools only reach deployment 5% of the time. They might have a high enough return they still come out ahead, but that is a high failure rate if you actually fully scrap the other 95% and don’t learn from them. It seems like this is a skill issue?

That sounds like the ‘AI tools’ that fail deserve the air quotes.

I also note that later they say custom built AI solutions ‘fail twice as often.’ That implies that when companies are wise enough to test solutions built externally, they succeed over 50% of the time.

Claims Of Zero Returns Do Not Mean What You Might Think

There’s also a strange definition of ‘zero return’ here.

Issue a report where you call the 95% of projects that don’t have ‘measurable P&L impact’ failures, then wonder why no one wants to do ‘high-ROI back office’ upgrades.

Those projects are high ROI, but how do you prove the R on I?

Especially if you can’t see the ROI on ‘enhancing individual productivity’ because it doesn’t have this ‘measurable P&L impact.’ If you double the productivity of your coders (as an example), it’s true that you can’t directly point to [$X] that this made you in profit, but surely one can see a lot of value there.

Crossing The Divide

They call it a ‘divide’ because it takes a while to see returns, after which you see a lot.

This all sounds mostly like a combination of ‘there is a learning curve that is barely started on’ with ‘we don’t know how to measure most gains.’

Also note the super high standard here. Only 22% of major sectors show ‘meaningful structural change’ at this early stage, and section 3 talks about ‘high adoption, low transformation.’

Or their ‘five myths about GenAI in the Enterprise’:

Most jobs within a few years is not something almost anyone is predicting in a non-AGI world. Present tense ‘transforming business’ is a claim I don’t remember hearing. I also hadn’t heard ‘the best enterprises are building their own tools’ and it does not surprise me that rolling your own comes with much higher failure rates.

I would push back on #3. As always, slow is relative, and being ‘eager’ is very different from not being the bottleneck. ‘Explored buying an AI solution’ is very distinct from ‘adopting new tech.’

I would also push back on #4. The reason AI doesn’t yet integrate well into workflows is because the tools are not yet good enough. This also shows the mindset that the AI is being forced to ‘integrate into workflows’ rather than generating new workflows, another sign that they are slow in adopting new tech.

I mean ChatGPT does now have some memory and soon it will have more. Getting systems to remember things is not all that hard. It is definitely on its way.

Unrealistic (or Premature) Expectations

The more I explore the report the more it seems determined to hype up this ‘divide’ around ‘learning’ and memory. Much of the time seems like unrealistic expectations.

Yes, you would love if your AI tools learned all the detailed preferences and contexts of all of your clients without you having to do any work?

Well, how would it possibly know about client preferences or learn from previous edits? Are you keeping a detailed document with the client preferences in preferences.md? People would like AI to automagically do all sorts of things out of the box without putting in the work.

And if they wait a few years? It will.

Claims Of Prohibitive Lock-In Effects Are Mostly Hype

I totally do not get where this is coming from:

Why is there a window and why is it closing?

I suppose one can say ‘there is a window because you will rapidly be out of business’ and of course one can worry about the world transforming generally, including existential risks. But ‘crossing the divide’ gets easier every day, not harder.

Why do people keep saying versions of this? Over time increasingly capable AI and better AI tools will make it, again, easier not harder to pivot or migrate.

Yes, I get that people think the switching costs will be prohibitive. But that’s simply not true. If you already have an AI that can do things for your business, getting another AI to learn and copy what you need will be relatively easy. Code bases can switch between LLMs easily, often by changing only one to three lines.

Nothing Ever Changes About Claims That Nothing Ever Changes

What is the bottom line?

This seems like yet another set of professionals putting together a professional-looking report that fundamentally assumes AI will never improve, or that improvements in frontier AI capability will not matter, and reasoning from there. Once you realize this implicit assumption, a lot of the weirdness starts making sense.

The reason this is worth so much attention is that we have reactions like this one from Matthew Field, saying this is a ‘warning sign the AI bubble is about to burst’ and claiming the study caused a stock selloff, including a 3.5% drop in Nvidia and ~1% in some other big tech stocks. Which isn’t that much, and there are various alternative potential explanations.

The improvements we are seeing involve not only AI as it exists now (as in the worst it will ever be), with substantial implementation delays. It also involves only individuals adopting AI or at best companies slotting AI into existing workflows.

Ask What AI Can Do For You

Traditionally the big gains from revolutionary technologies come elsewhere.

I do think it is going faster and will go faster, except that in AI the standard for ‘fast’ is crazy fast, and ‘AIs coming up with great ideas’ is a capability AIs are only now starting to approach in earnest.

I do think that if AGI and ASI don’t show up, the timeline to the largest visible-in-GDP gains will take a while to show up. I expect visible-in-GDP soon anyway because I think the smaller, quicker version of even the minimally impressive version of AI should suffice to become visible in GDP, even though GDP will only reflect a small percentage of real gains.

The Pattern Of Claiming a Slowdown Continues

The ‘AI is losing steam’ or ‘big leaps are slowing down’ and so on statements from mainstream media will keep happening whenever someone isn’t feeling especially impressed this particular month. Or week.

Peter links to about 35 posts. They come in waves.

The practical pace of AI progress continues to greatly exceed the practical pace of progress everywhere else. I can’t think of an exception. It is amazing how eagerly everyone looks for a supposed setback to try and say otherwise.

You could call this gap a ‘marketing problem’ but the US Government is in the tank for AI companies and Nvidia is 3% of total stock market cap and investments in AI are over 1% of GDP and so on, and diffusion is proceeding at record pace. So it is not clear that they should care about those who keep saying the music is about to stop?

A Sensible Move

Coinbase CEO fires software engineers who don’t adopt AI tools. Well, yeah.

Who Deserves The Credit And Who Deserves The Blame

On the one hand, AI companies are building their models on the shoulders of giants, and by giants we mean all of us.

Also the AI companies are risking all our lives and control over the future.

On the other hand, notice that they are indeed not making that much money. It seems highly unlikely that, even in terms of unit economics, creators of AI capture more than 10% of value created. So in an ‘economic normal’ situation where AI doesn’t ‘go critical’ or transform the world, but is highly useful, who owes who the debt?

It’s proving very useful for a lot of people.

All of these uses involve paying remarkably little and realizing much larger productivity gains.

Mistakes From Applying Standard Economics To Future AIs

Steven Byrnes explains his view on some reasons why an economics education can make you dumber when thinking about future AI, difficult to usefully excerpt and I doubt he’d mind me quoting it in full.

I note up top that I know not all of this is technically correct, it isn’t the way I would describe this, and of course #NotAllEconomists throughout especially for the dumber mistakes he points out, but the errors actually are often pretty dumb once you boil them down, and I found Byrnes’s explanation illustrative.

Yep. If you restrict to worlds where collaboration with humans is required in most cases then the impacts of AI all look mostly ‘normal’ again.

I am under no illusions that an explanation like this would satisfy the demands and objections of most economists or fit properly into their frameworks. It is easy for such folks to dismiss explanations like this as insufficiently serious or rigerous, or simply to deny the premise. I’ve run enough experiments to stop suspecting otherwise.

However, if one actually did want to understand the situation? This could help.