I think you're overstating your case on Science Beakers. Take the example of titanium, as described here. In short, what happened was:

- Basic research happened, leading to small-scale production and basic knowledge of its properties.

- People (including the US government) started spending science beakers on the Titanium tech node.

- Through experience and research, they learned stuff like the fact that cadmium-coated wrenches are bad.

- Now, we can effectively work titanium.

If it wasn't for the A-12 project (and its precursors and successors), then we simply wouldn't be able to build things out of titanium. No reasonable amount of non-titanium background research would get an engineer to check their marking pen for chloride-based inks or discover osseointegration.

I haven't looked into supersonic flight technology, but I'd be shocked if they discovered nothing new from the design and operation of the Concorde.

If it wasn't for the A-12 project (and its precursors and successors), then we simply wouldn't be able to build things out of titanium.

That is not an accurate summary of the linked article.

In 1952, another titanium symposium was held, this one sponsored by the Army’s Watertown Arsenal. By then, titanium was being manufactured in large quantities, and while the prior symposium had been focused on laboratory studies of titanium’s physical and chemical properties, the 1952 symposium was a “practical discussion of the properties, processing, machinability, and similar characteristics of titanium". While physical characteristics of titanium still took center stage, there was a practical slant to the discussions – how wide a sheet of titanium can be produced, how large an ingot of it can be made, how can it be forged, or pressed, or welded, and so on. Presentations were by titanium fabricators, but also by metalworking companies that had been experimenting with the metal.

That's before the A-12.

In 1966, another titanium symposium was held, this one sponsored by the Northrup Corporation. By this time, titanium had been used successfully for many years, and the purpose of this symposium was to “provide technical personnel of diversified disciplines with a working knowledge of titanium technology.” This time, the lion’s share of the presentations are by aerospace companies experienced in working with the metal, and the uncertain air that existed in the 1952 symposium is gone.

At that point, the A-12 program was still classified and the knowledge gained from it was not widely shared.

Key paragraph:

The A-12 “practically spawned its own industrial base” (CIA 2012), and over the course of the program thousands of machinists, mechanics, fabricators, and other personnel were trained in how to work with titanium efficiently. As Lockheed gained production experience with titanium, it issued reports to the Air Force and to its vendors on production methods, and “set up training classes for machinists, a complete research facility for developing tools and procedures, and issued research contracts to competent outside vendors to develop improved equipment" (Johnson 1970).

The 1952 symposium is clearly a precursor to its 1959-1964 production and development, and the 1966 one is drawing from the experiences of the industrial base it created.

EDIT: and more directly:

What can we learn from the story of titanium?

For one, titanium is a government research success story. Titanium metal was essentially willed into existence by the US government, which searched for a promising production process, successfully scaled it up when it found one, and performed much of the initial research on titanium’s material properties, potential alloys, and manufacturing methods. Nearly all early demand for titanium was for government aerospace projects, and when the nascent industry struggled, the government stepped in to subsidize production. As a result, titanium achieved a level of production in 10 years that took aluminum and magnesium nearly 30.

While I still disagree with your interpretation of that post, I don't want to argue over the meaning of a post from that blog. There are actual books written about the history of titanium. I'm probably as familiar with it as the author of Construction Physics, and saying A-12-related programs were necessary for development of titanium usage is just wrong. People who care about that and don't trust my conclusion should go look up good sources on their own, more-extensive ones.

A century ago, it was predicted that by now, people would be working under 20 hours a week.

And this prediction was basically correct, but missed the fact that it's more efficient to work 30-40 hours per week while working and then take weeks or decades off when not working.

The extra time has gone to more leisure, less child labor, more schooling, and earlier retirement (plus support for people who can't work at all).

I grew up in India, and DDT is good actually. It's sprayed once or twice a year, and the decrease in the number of mosquitoes after the spray is dramatic. Even ignoring the reductions in malaria, dengue, etc. it becomes markedly less unpleasant to be outdoors.

Sure, there are other molecules that work, and it may well be true that "the only advantage DDT has over those is lower production cost," but that's a big fucking advantage. I suppose you could apply the expensive stuff to your backyard or something, but cheap stuff makes it possible to spray the streets of every village in the country.

And regarding "environmental harms," from personal experience scratching myself bloody as a kid from itchy bites after going to the park in the evening, I would extinct a dozen species if mosquitoes went down with them.

As a side note, without looking it up, I bet the drive to switch from DDT to newer compounds, pyrethroids or whatever else, kicked off just as the old patents expired, just like what happened with CFCs and DuPont's patents.

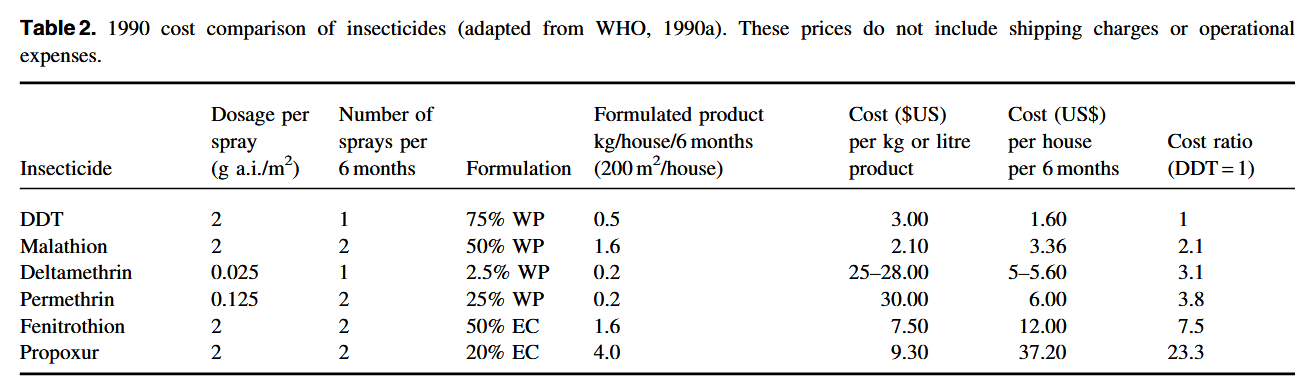

Found this paper on insecticide costs: https://sci-hub.st/http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2915.2000.00262.x

It's from 2000, so anything listed here would be out of patent today.

Here are the costs from the above link:

It's worth noting that countries (such as India) have the option of simply not respecting a patent when the use is important and the fees requested are unreasonable. Also, patents aren't international; it's often possible to get around them by simply manufacturing and using a chemical in a different country.

The only advantage DDT has over those is lower production cost, but the environmental harms per kg of DDT are greater than the production cost savings, so using it is just never a good tradeoff.

As I said, if DDT was worth using there, it was worth spending however much extra money it would have been to spray with other things instead. If it wasn't worth that much money, it wasn't worth spraying DDT.

And regarding "environmental harms," from personal experience scratching myself bloody as a kid from itchy bites after going to the park in the evening, I would extinct a dozen species if mosquitoes went down with them.

The biggest problem with DDT is that it is bad for humans.

I don't think even libertarian techno-optimists would be happy about me blogging about bioweapon design.

Without doing the "No True Libertarian Techno-Optimist" thing about everyone else, I would be. And for precisely the same reasons a "libertarian techno-optimist" would favor decentralized power and distributed knowledge anywhere else, just without any special pleading about this.

"If democracy is failing, it's because of people like you."

That's high praise to anyone doesn't like democracy and wants it to fail. I don't know much about Luckey, but if he's anything like Thiel, that includes him.

You would be happy about more people blogging about bioweapon design? Hmm.

I think you don't realize quite how much danger we are all in from a bad actor developing and releasing bioweapons. More information about that on the internet would make it easier for people to google it, and would make more training data about it available to future to LLMs. I can't see how that's anything but bad for humanity.

I don't think you are saying that you want to murder billions of innocent people or destroy modern civilization, but it seems like you are arguing for something that would make it easier for people to do those things.

Bioweapon Biological research is dual-use technology. I believe there are many great things people can achieve if knowledge and capabilities in this field were widely accessible instead of being restricted to powerful well-resourced groups as they are now, the most obvious of which is at-home drug synthesis, but includes biohacking/gene therapies, engineered foods, designer babies, gene drives (to eradicate mosquitoes), deëxtinction (to bring them back). I also expect there'd be clever applications I haven't thought of, but someone else will; I do not believe myself to be smarter than the rest of mankind put together. Basically anything the FDA would regulate and inhibit, I hope to see democratized[1] beyond its reach.

I wouldn't describe myself as having any particular desire to "murder billions of innocent people." I estimate I'm well within 3-sigma of the mean by that metric, entirely unremarkable.

I am also emphatically against any kind of "degrowth" or primitivism, so if that's what you mean by "destroy modern civilization," I'm at perhaps 5-sigma in the opposite direction. But if you instead mean something like the abolition of the Administrative State, yeah, that's something I am strongly in favor of.

- ^

I hope at this point, it's clear I mean empowering individuals and not the "democratically elected governments" that rule them.

I partially agree with @ulyssessword that while this article has valuable insights, it overstates the case.

What Civ gets "wrong" (by making it a simple game mechanic) is treating basic and applied research, on platform and specific technologies, work the same way, and also by letting the player know in advance how many Science Beakers lie between here and there for each.

If you know what problem you need to solve, and the general shape of what a solution could look like, you can throw more money and minds at it and get there faster than you counterfactually would.

If not, then more minds and money spent broadly will still directionally produce more research which can be turned into more innovations, but you won't be able to say in advance how many turns faster you'll get to any particular invention, or what order you'll get them in.

You don't have literally zero knowledge, you can be usefully clever, but you don't have Civ-like control. Cities and countries with better laws, infrastructure, business culture, ESOs, investors, and baseline wealth levels really do reliably generate and roll out more and better Technology (TM) across the board, and this replicates to a significant degree, and where it fails it's often pretty easy to do a post- (or, yes, pre-) mortem to figure out what did (will) go wrong and how to do better.

In other words, research turns money into knowledge, and innovation turns knowledge into money; both processes are error prone and inefficient, but there is still a range of better and worse ways to manage each; and doing more of either will put you in a position to do more of the other.

tech trees

There's a series of strategy games called Civilization. In those games, the player controls a country which grows and develops over thousands of years, and science is one of the main types of progress. It involves building facilities to generate research points, sometimes represented by Science Beakers filled with Science Fluid, and using those points to buy tech nodes on a tree.

I'm reminded of the above game mechanic when I see certain comments on blogs or Twitter/X. I'll use supersonic aircraft as an example.

supersonic aircraft

Several times, I've seen comments online similar to: "Look at this graph of aircraft speeds going up and then stopping. People should be forced to deal with sonic booms so we can have supersonic aircraft and get back to progress. It will be unpopular but this is more important than democracy."

In their mind, society has a "tech node" called "supersonic flight" and you need to finish the node before you can move to the next node. If opponents cause society to not finish the node, then you're stuck. But that's not how tech progress works. How much further would we be from supersonic transports today if the Concorde had never flown? The answer is 0.

There's a lot of underlying progress required for something like, say, a high-performance gas turbine. The abstract progress is more general, and each practical application involves different specifics. Understanding principles of metallurgy and how to examine metals leads to specific high-temperature alloys, which are what actually get used. Funding for gas turbine development can lead to single-crystal casting or turbine blade film cooling being developed, but the actual production of a new gas turbine model has no effect on whether that's developed.

The tech tree of a game like Civilization would be more accurate if it had a 3rd dimension, with height representing the abstract and general vs the practical and specific. Something like the Concorde would be on a vertical offshoot off the tree. But game systems representing something complex are simplified in ways that appeal to players.

Similarly, Boom Technology Inc working on a prototype for a supersonic plane does zero to bring the world closer to economically practical supersonic transport, because the underlying technology for that isn't there and they're not working on it. The best-case scenario for something like Boom Technology isn't "cheap supersonic flight", it's "a new resource-consuming luxury for rich people to spend money on that also makes the lives of most people a bit worse", or perhaps "a supersonic military UAV".

Similarly, I've seen people make charts of progress on humanoid robots that go like:

early robot 🡲 ASIMO 🡲 Atlas from Boston Dynamics 🡲 new thing

But ASIMO had no impact on later development of humanoid robots, and Boston Dynamics didn't invent the actuators used in their new robots or contribute to the modern neural network designs now used for computer vision. What was important was development of the underlying technologies: lightweight electric motors, power electronics, batteries, high-torque actuators, processors, and machine learning algorithms. To the extent that there's a "tech tree" involved, it's a fractal tree where the "nodes" are arcane things like semiconductor processing steps.

Trying to implement something when the underlying tech to make it practical isn't there yet can sometimes actually delay usage of it. To investors, "hasn't been tried" sounds a lot better than "was tried already and failed".

civics trees

— the BBC

In Civilization 6, there are 2 separate tech trees, 1 for science and 1 for cultural development.

Sometimes you see people who want to ban all cars in all cities. It's not "I want to live in a city where I don't have to drive", it's "We need to change all cities so cars aren't used for transporting people, because that's The Future." Like they want to finish the "post-car cities" civic node.

To someone mainly concerned with tech progress, every regulation obstructing finishing the next tech node has to be torn down. But to someone mainly concerned with social technology, saying "regulations are bad because they don't let tech people do what they want" is like saying "pipes are bad because they don't let fluids do what they want".

If tech trees can only go forwards, then every change is progress. If change can only happen along tech trees, then the only options are "return to the previous node" and "advance to the next node". This is the fundamental similarity between the "tech tree" and "civics tree" people.

Sometimes you get people whose ideas of progress are linear and contradictory at some point, and then they have to fight endlessly over progress towards the "nuclear abolition civic" node vs progress towards the "advanced nuclear power tech" node. And then if you say something like "nuclear plants can be safe but the fans of them don't take safety seriously enough" or "nuclear waste is manageable but nuclear power is currently too expensive for reasons other than unnecessary regulations" then it only makes you enemies on both sides, because even if you partly agree with them you're still in the way of what they want to do.

Science Beakers

The other aspect of research in Civilization games I wanted to talk about was the "research points". A lot of people really do have this idea that professors and grad students basically fill up Science Beakers with Science Fluid and then the Scientific Process converts the Science Beakers into Progress.

People can think of research that way while understanding there's randomness, that perhaps only a fraction of research ultimately matters, but they think of that like gambling, like trying to pull "New medicine developed!" in a gacha game. That's not my experience. More experiments can collect more data, but if there's already enough data, then getting more data doesn't help you put the right data together into a concept. And research trying to prove the Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer's doesn't help you understand what's actually going on.

You also can't feed your Science Beakers to The Scientific Process, because there is no Scientific Process that every scientist uses. There are just cultures of scientific fields, and there's some crossover and convergent evolution, but different fields do things differently. Every "key aspect of science" in popular culture isn't actually necessary:

Back in 1920 a NYT editorial said rockets were logically impossible, and I've seen that referenced by people saying "nobody really knows what will work, so you just have to experiment randomly". But engineers actually did understand Newton's laws of motion in 1920; that's just an example of the NYT having no competence in science or engineering.

concept overbundling

People bundle concepts together to simplify thinking. That's inevitable, but when someone cares greatly about a complex issue, they should put some effort into understanding its components.

When people don't do this, it's tempting to call it "lack of curiosity" or "stupidity", but consider the sources people read. People look to experts for how and when they should break down concepts. If you look at, say, bike enthusiasts, they often have strong opinions about details of gear reducers or drive systems or tire styles. Meanwhile, "nutrition enthusiasts" are often focused on one particular thing that doesn't even matter that much, despite (I hope I'm not offending the bike people) nutrition being more complex than bicycles. I think this is a result of the content of information sources about bikes vs nutrition, which in turn is a result of incentives and network effects.

my view

gradient descent

I don't think of science or culture as progressing through a tree of nodes. Rather, I think of the evolution of them over time as being like unstable gradient descent on a high-dimensional energy landscape, which is similar enough to training of a large neural network to have some similar properties. I've made that analogy previously.

tech selection

My view is that potential technology is neutral on average, but developed and implemented technology tends to be somewhat good on average. That is, I think tech is only good because of the choices made about it.

Researchers, regulators, companies, and individuals all have different information and incentives regarding new technology. In that kind of situation, I think everyone should do a little bit. Meaning, a bit of researchers choosing their topics, a bit of regulation, and a bit of individuals choosing how to use the things developed.

Different people will advocate for more or less influence of particular levels, and there's an equilibrium, a balance of power between people with tendencies towards different views. Some people strongly want researchers and regulators to be less selective, but I don't think even libertarian techno-optimists would be happy about me blogging about bioweapon design.

Wirth's Law

— President Bush in 2005, speaking to a divorced mother of three

It's been widely said that software expands to consume the available resources. Computers get faster, and software gets slower...up to the point where it starts actually causing problems. Large companies release video games or use websites that have performance slow enough to cause major problems. The existence of such failure is the force pushing institutions towards competence, and without that, they get worse over time until failure starts happening.

A century ago, it was predicted that by now, people would be working under 20 hours a week. Apologist economists will sometimes say things like, "But now you want a computer and Netflix" but you can have both for $30 a month. What about the rest of those extra work hours? Better-quality housing? People living in 60-year-old houses aren't paying dramatically less rent.

It's true that productivity at farms and factories has improved massively. Computers should theoretically be a comparable improvement to office work. Where has that extra productivity gone? It's gone to time spent in meetings and classes and bullshit jobs that are, from a global perspective, useless. (Also, to luxuries for the ultra-wealthy, and supporting the people providing those luxuries.) I could post more things than I do, but...what's the point of more technology if it just gives institutions more room to be corrupt?

DDT

— Palmer Luckey

Quite the title on that article there. More competition is fine and all, but "American Vulcan"? Big words for making a company with designs worse than Northrop's and DFM worse than China's. Kratos Defense seems more competent, but somehow Anduril has a much higher valuation; I guess that's the power of influential VCs.

DDT is bad, actually

I didn't expect, in the year 2024, to have a need to argue about DDT. But here I am. I guess I can talk about some heuristics for molecular toxicology.

When you have aromatics with halogens on them, they're relatively likely to be endocrine disruptors. And indeed, the problem DDT is best known for is it being an endocrine disruptor. PBDEs are bad for the same reason.

When you have aromatics without any hydrophilic groups on them, they might be oxidized to epoxides by p450 oxidases. That's why benzene is toxic: it's oxidized to benzene oxide in an interesting reaction. And indeed, DDT is metabolized by p450s to products including epoxides. So, we should expect DDT to be bad in similar ways to benzene - that is, genotoxic and carcinogenic.

Compounds designed to kill a certain kind of organism are more likely to harm similar organisms. DDT was designed to kill mosquitos, so it might be bad for other insects. And indeed, it kills bees pretty effectively, as do many insecticides.

When you have a molecule like DDT without any of the functional groups that make enzymatic processing easier, it tends to be metabolized slowly. When you have a slowly-metabolized molecule that's hydrophobic with moderate aprotic polarity, it tends to build up in fats, and then biomagnification happens as predators eat prey. And indeed, DDT has biomagnification, and levels got high enough in birds and larger fish to be a real problem.

Of course, that only covers half the argument about DDT. Advocates for it say, "DDT isn't bad, but even if it is, it still saves lives, so bans on it mean more deaths". But that's wrong too.

There is no global ban on DDT; a few countries are still using it, notably India. The biggest use of DDT was for agriculture, and even if malaria is the only thing you care about, you shouldn't want DDT used on crops. Insects can and have evolved resistance to DDT, and reduced use of it on crops delayed resistance to it in mosquitoes.

People decided DDT isn't worthwhile largely because pyrethroids are a better option; they basically do the same thing to insects but with more specificity. The only advantage DDT has over those is lower production cost, but the environmental harms per kg of DDT are greater than the production cost savings, so using it is just never a good tradeoff.

Well, the above is just a half-assed side-note of this post covering what I already knew; I could certainly be more thorough. Since Palmer is still so proud of his debate-club arguments for DDT, I'd be happy to provide another chance to show them off by publicly debating him.

circular reasoning

When someone like Palmer does something like advocate for DDT, what's the mindset involved? I think it's basically circular logic:

Even when each point is correct (which they aren't here) you're obviously supposed to compensate for that kind of looping feedback, but some people don't.

anti-democratic tendencies

For the sake of progress, some people want to force everyone to deal with sonic booms, and Palmer wants to force those silly environmentalists to put up with some chemicals they dislike. "Progress", in the mind of Palmer Luckey, being a return to mass production of a particularly toxic chemical that was replaced decades ago by more-complex but superior alternatives. Sigh. I'm talking about a billionaire here yet I feel like I'm shooting fish in a barrel; I guess that's what happens when I'm used to fans of LoGH or Planetes and I'm talking about a fan of Yugioh and SAO.

Government regulations and agencies have a lot of problems and poor decisions. I'm sympathetic to calls for changing them, but I've lost track of how many times I've seen an article by some pundit or economist or CEO saying "This government agency is flawed...and that's why we need to override it to do [something extremely stupid]." I've seen people extremely mad about things such as:

As bad as things are in government regulatory agencies these days, on average, the suggestions for changes I've seen in magazine/newspaper articles have generally been worse. But some people take it to the next level by saying that their favorite stupid idea not being implemented means democracy is a failure. To them I'd say, "If democracy is failing, it's because of people like you."

learn some humility

— Tokugawa Ieyasu

I like that quote, but many powerful people don't seem to understand its meaning. Some people succeed because of luck or their family, and the conclusion they make is that they're always right. Some people believe in X, then X happens to be true for their case, and the conclusion they make is that X is always true.