In Part One, we explore how models sometimes rationalise a pre-conceived answer to generate a chain of thought, rather than using the chain of thought to produce the answer. In Part Two, the implications of this finding for frontier models, and their reasoning efficiency, are discussed.

TLDR

Reasoning models are doing more efficient reasoning whilst getting better at tasks such as coding. As models continue to improve, they will take bigger reasoning jumps which will make it very challenging to use the CoT as a method of interpretability. Further into the future, models may stop using CoT entirely and move towards reasoning directly in the latent space - never reasoning using language.

Part 1: Experimentation

The (simplified) argument for why we shouldn’t rely on reading the chain of thought (CoT) as a method of interpretability is that models don’t always truthfully say how they have reached their answer in the CoT. Instead, models sometimes use CoT to rationalise answers that they have already decided on. This is shown by Turpin et al where hints were added to questions posed to reasoning models and the impact of this on the CoT was observed: the hints were used by the model to arrive at its answer, but they were not always included in the CoT. This implies that, in its CoT, the model was just rationalising an answer that it had already settled on. We don’t want a model’s rationalisation of an answer, we want to know how it arrived there!

Recreating hint results

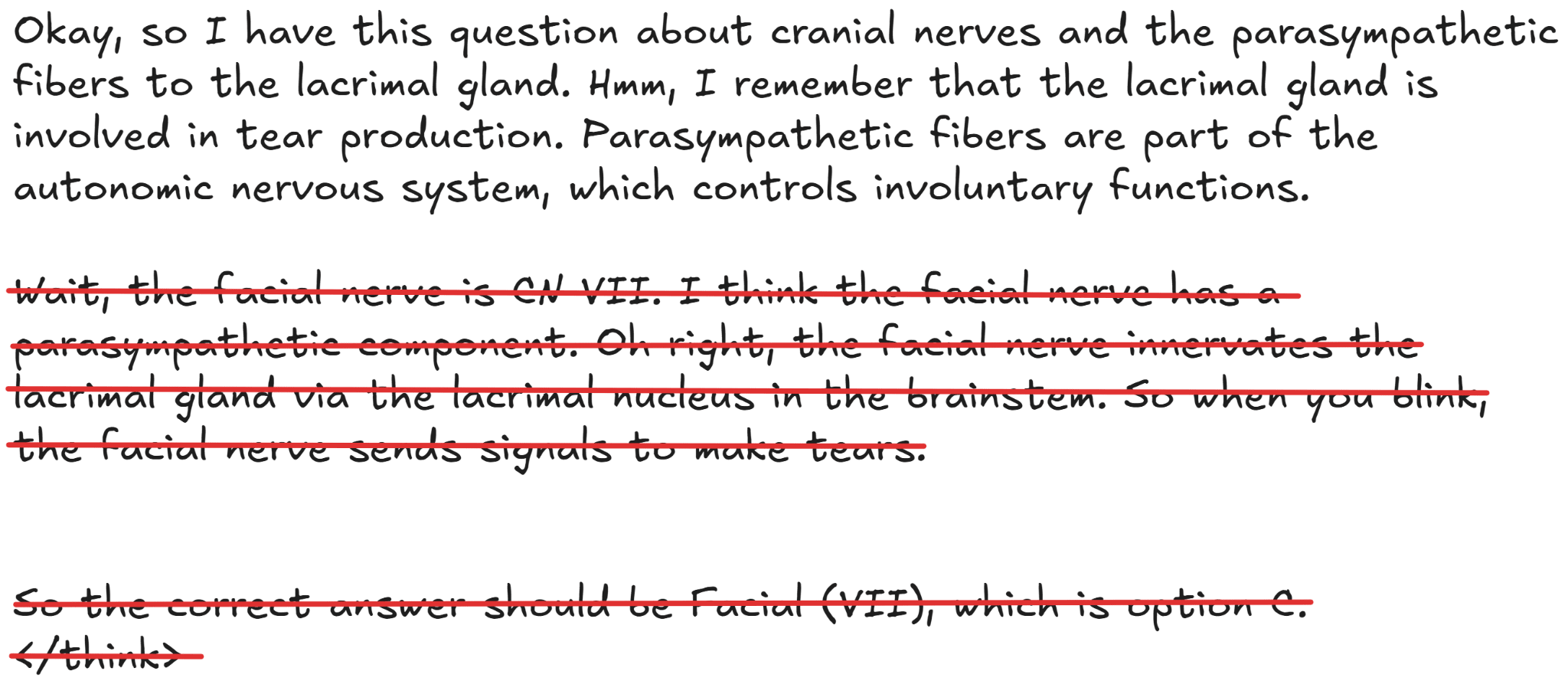

The DeepSeek R1-Distill Qwen-14B model (48 layers) is used. In this section we will focus on the visual hint example shown in Figure 1, but you can see the other prompts used in the Github repo. Both few shot visual hints (Figure 1) and few shot always option A hint prompts were used.

In Figure 1 in the hinted prompt, a square was placed next to the correct multiple choice option.

Figure 1: Control and “hinted” prompt - hinted prompt has a ■ next to the answer

Figure 2 shows the responses to the prompts. Both prompts arrive at the same answer yet the hinted prompt has much more direct reasoning and uses filler phrases such as “Wait”, “Hmm”, “Let me think”, “Oh” less. The hinted prompt uses ~40% fewer tokens than the control prompt, while still arriving at the same answer. Notice that the hinted prompt never mentions that it used the hint.

Sentence impact

To investigate this further, I used counterfactual resampling. Counterfactual resampling works by prompting the model with its original CoT for that prompt but with different sentences removed. The approach was to run a resampling test for every one of the ten sentences in the control CoT. Each of the ten sentences were resampled ten times to get a better sample of how the model behaves.

Counterfactual resampling allows us to see what impact that sentence has on the structure of the reasoning and on the answer. Figure 3 shows the original CoT (including the crossed out sentences) and the CoT passed into the resampling prompt for when sentence 3 and all following sentences are removed. Figure 5 shows the difference in CoT when sentence 3 is removed. Figure 3: Counterfactual resampling example - baseline CoT shown with red line showing the removal of sentence 3 and onwards. The non-crossed sentences are combined with the original prompt to investigate how the reasoning is affected.

When working on the prompt shown in Figure 1, removing sentences from the CoT did not change the model’s answer, only subtly changing the reasoning. An interesting insight was that the length of the CoT (almost always) decreased when sentences were removed. This suggests that the sentences that were removed were not necessary for the reasoning. This is particularly the case for sentence 3 (the large decrease in characters shown in Figure 4) “Wait, the facial nerve is CN VII” where the mean length decreased by over 300 characters. The different CoTs are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4: Mean length (in characters) of resampling completion compared to the original CoT length.

Looking at sentence 3 resampling in more detail, Figure 5 shows that the original CoT following sentence 3 is much longer. Although the resampled CoT is more compact, it also contains more filler phrases. The cause of this is not understood.

CoT rationalisation?

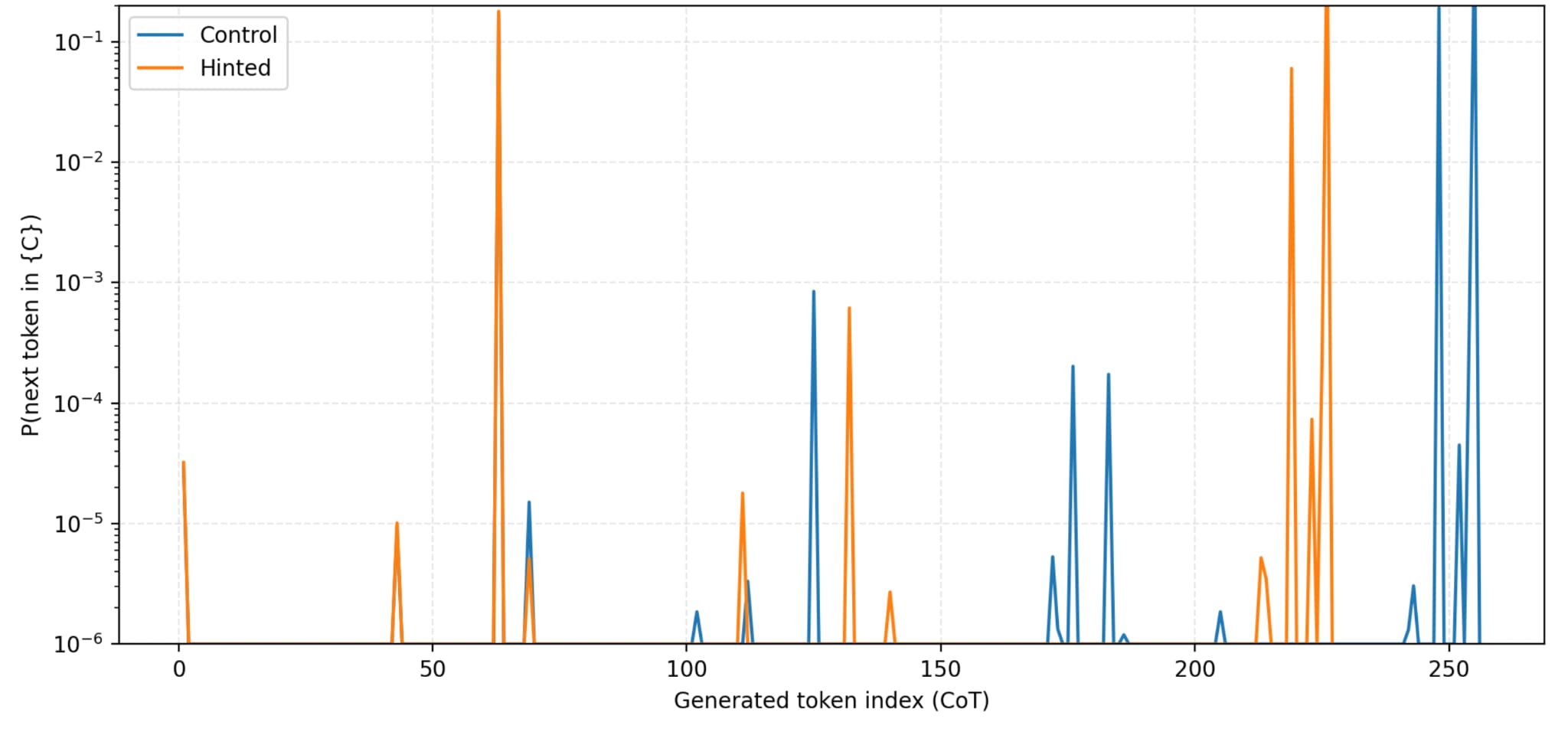

During the CoT generation, the likelihood that the next token would be “C” (the correct option to the question being tested) was also assessed. Figure 6 shows that the hinted prompt is much more likely to immediately say C than the control prompt. It also has many earlier spikes than the control prompt. This might suggest that the model is rationalising the CoT as it already knows that it wants to say C, but the evidence is not conclusive. This is discussed further in the “Reflections and next steps” section. Figure 6: Probability that the next token is “C” according to logits during CoT generation.

Reflections and next steps

The counterfactual resampling and next token is “C” experiments have shown some evidence that, in the context of giving the model a hint, the CoT is rationalised rather than used to generate the answer to the question.

However, it is unsurprising that the model recognises the visual pattern and uses it to realise that the answer could be “C”. What would be more interesting is the application of a similar test to a scenario with a simple question - one that a model could work out without any reasoning - and see if it knows the answer to the question before doing any reasoning. It would be interesting to find out at what prompt difficulty a model stops rationalising its CoT and starts using it for actual reasoning.

This was a productive task to explore what techniques could be used on a project such as this. While working on this article, I tried some different approaches that I haven’t included such as training a probe to recognise what MCQ answer the model was thinking of at different points of the CoT. I decided to use the most likely next MCQ option token instead of this as the probe was very noisy and didn’t offer much insight. Although the most likely next MCQ option token isn’t ideal either - the model has been finetuned to reason so it won’t have a high logit on MCQ options even if it does already know the answer to the question.

I need a better way of assessing the model’s MCQ option “confidence”. I would appreciate any suggestions!

How do the experiments relate to model efficiency?

In this article I have suggested that models sometimes rationalise a pre-conceived answer with their CoT rather than doing actual reasoning in it, meaning that sometimes what the model is saying in its CoT isn’t actually what it is doing to reach its answer. Sometimes the model is able to make a reasoning jump straight to the answer. Furthermore, in Figure 4 I showed that resampling the original CoT by removing different sentences can decrease the length of the CoT without changing the answer, suggesting that some sentences in the CoT are not vital for reasoning. This claim is explored in much more depth in Bogdan et al.

If some of the sentences (or the whole CoT) are not vital for reasoning, then models should learn to remove them from their CoT to allow them to hold more effective reasoning in their limited context to help them tackle more complex problems.

If models are able to drastically increase the size of the reasoning jumps (stop rationalising in the CoT and just reason) that they are able to take inside the CoT (for increased efficiency) then we won’t be able to use the CoT to monitor in enough detail what the model is doing for it to reach its answer.

We can already see these efficiency gains happening with frontier LLMs.

Part 2: Trends at the frontier

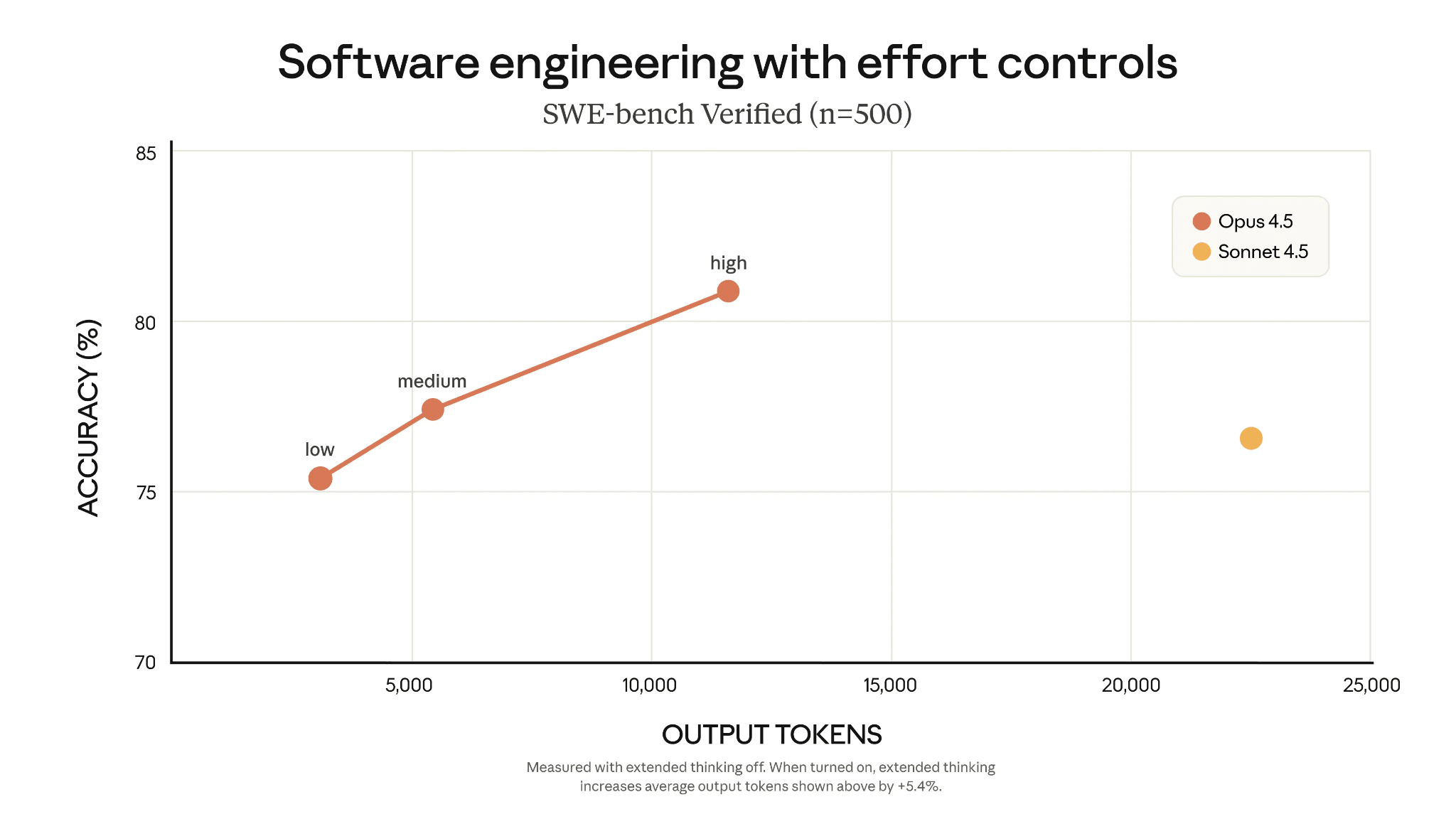

As models get more intelligent and are able to make bigger jumps without spelling out their reasoning, we will be unable to see what the model is doing to reach its answer in the CoT. We can see this improved reasoning efficiency trend by examining the efficiency gains made by recent frontier models. Figure 7: SWE-bench accuracy of Opus 4.5 with effort controls low, medium, high compared to sonnet 4.5 (Opus 4.5 announcement)

In the Opus 4.5 announcement, we see that Opus 4.5 (a larger model) is able to match Sonnet 4.5’s performance on SWE-bench whilst using 76% fewer tokens. Both Opus 4.5 and Sonnet 4.5 are frontier models from Anthropic. Opus is larger and more token efficient meaning it is able to be more effective with the use of its reasoning, suggesting it is able to make larger reasoning jumps than Sonnet.

Latent reasoning (where reasoning is done solely in the activation space - no language reasoning) seems to be a promising research direction. The concept can be seen in Figure 8. Instead of outputting in English, the activations from the final hidden state are put through the model again as input embeddings for the next forward pass.

Maybe this could be seen as CoT efficiency at the limit. All reasoning jumps are done internally, with no need to reason in language for us to interpret how the model reached its answer.

In Part One, we explore how models sometimes rationalise a pre-conceived answer to generate a chain of thought, rather than using the chain of thought to produce the answer. In Part Two, the implications of this finding for frontier models, and their reasoning efficiency, are discussed.

TLDR

Reasoning models are doing more efficient reasoning whilst getting better at tasks such as coding. As models continue to improve, they will take bigger reasoning jumps which will make it very challenging to use the CoT as a method of interpretability. Further into the future, models may stop using CoT entirely and move towards reasoning directly in the latent space - never reasoning using language.

Part 1: Experimentation

The (simplified) argument for why we shouldn’t rely on reading the chain of thought (CoT) as a method of interpretability is that models don’t always truthfully say how they have reached their answer in the CoT. Instead, models sometimes use CoT to rationalise answers that they have already decided on. This is shown by Turpin et al where hints were added to questions posed to reasoning models and the impact of this on the CoT was observed: the hints were used by the model to arrive at its answer, but they were not always included in the CoT. This implies that, in its CoT, the model was just rationalising an answer that it had already settled on. We don’t want a model’s rationalisation of an answer, we want to know how it arrived there!

Recreating hint results

The DeepSeek R1-Distill Qwen-14B model (48 layers) is used. In this section we will focus on the visual hint example shown in Figure 1, but you can see the other prompts used in the Github repo. Both few shot visual hints (Figure 1) and few shot always option A hint prompts were used.

In Figure 1 in the hinted prompt, a square was placed next to the correct multiple choice option.

Figure 1: Control and “hinted” prompt - hinted prompt has a ■ next to the answer

Figure 2: Prompt responses. Left: control CoT. Right: visually hinted CoT

Figure 2 shows the responses to the prompts. Both prompts arrive at the same answer yet the hinted prompt has much more direct reasoning and uses filler phrases such as “Wait”, “Hmm”, “Let me think”, “Oh” less. The hinted prompt uses ~40% fewer tokens than the control prompt, while still arriving at the same answer. Notice that the hinted prompt never mentions that it used the hint.

Sentence impact

To investigate this further, I used counterfactual resampling. Counterfactual resampling works by prompting the model with its original CoT for that prompt but with different sentences removed. The approach was to run a resampling test for every one of the ten sentences in the control CoT. Each of the ten sentences were resampled ten times to get a better sample of how the model behaves.

Counterfactual resampling allows us to see what impact that sentence has on the structure of the reasoning and on the answer. Figure 3 shows the original CoT (including the crossed out sentences) and the CoT passed into the resampling prompt for when sentence 3 and all following sentences are removed. Figure 5 shows the difference in CoT when sentence 3 is removed.

Figure 3: Counterfactual resampling example - baseline CoT shown with red line showing the removal of sentence 3 and onwards. The non-crossed sentences are combined with the original prompt to investigate how the reasoning is affected.

When working on the prompt shown in Figure 1, removing sentences from the CoT did not change the model’s answer, only subtly changing the reasoning. An interesting insight was that the length of the CoT (almost always) decreased when sentences were removed. This suggests that the sentences that were removed were not necessary for the reasoning. This is particularly the case for sentence 3 (the large decrease in characters shown in Figure 4) “Wait, the facial nerve is CN VII” where the mean length decreased by over 300 characters. The different CoTs are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 4: Mean length (in characters) of resampling completion compared to the original CoT length.

Figure 5: Right: original CoT (after sentence 3). Left: resampled CoT (after sentence 3)

Looking at sentence 3 resampling in more detail, Figure 5 shows that the original CoT following sentence 3 is much longer. Although the resampled CoT is more compact, it also contains more filler phrases. The cause of this is not understood.

CoT rationalisation?

During the CoT generation, the likelihood that the next token would be “C” (the correct option to the question being tested) was also assessed. Figure 6 shows that the hinted prompt is much more likely to immediately say C than the control prompt. It also has many earlier spikes than the control prompt. This might suggest that the model is rationalising the CoT as it already knows that it wants to say C, but the evidence is not conclusive. This is discussed further in the “Reflections and next steps” section.

Figure 6: Probability that the next token is “C” according to logits during CoT generation.

Reflections and next steps

The counterfactual resampling and next token is “C” experiments have shown some evidence that, in the context of giving the model a hint, the CoT is rationalised rather than used to generate the answer to the question.

However, it is unsurprising that the model recognises the visual pattern and uses it to realise that the answer could be “C”. What would be more interesting is the application of a similar test to a scenario with a simple question - one that a model could work out without any reasoning - and see if it knows the answer to the question before doing any reasoning. It would be interesting to find out at what prompt difficulty a model stops rationalising its CoT and starts using it for actual reasoning.

This was a productive task to explore what techniques could be used on a project such as this. While working on this article, I tried some different approaches that I haven’t included such as training a probe to recognise what MCQ answer the model was thinking of at different points of the CoT. I decided to use the most likely next MCQ option token instead of this as the probe was very noisy and didn’t offer much insight. Although the most likely next MCQ option token isn’t ideal either - the model has been finetuned to reason so it won’t have a high logit on MCQ options even if it does already know the answer to the question.

I need a better way of assessing the model’s MCQ option “confidence”. I would appreciate any suggestions!

How do the experiments relate to model efficiency?

In this article I have suggested that models sometimes rationalise a pre-conceived answer with their CoT rather than doing actual reasoning in it, meaning that sometimes what the model is saying in its CoT isn’t actually what it is doing to reach its answer. Sometimes the model is able to make a reasoning jump straight to the answer. Furthermore, in Figure 4 I showed that resampling the original CoT by removing different sentences can decrease the length of the CoT without changing the answer, suggesting that some sentences in the CoT are not vital for reasoning. This claim is explored in much more depth in Bogdan et al.

If some of the sentences (or the whole CoT) are not vital for reasoning, then models should learn to remove them from their CoT to allow them to hold more effective reasoning in their limited context to help them tackle more complex problems.

If models are able to drastically increase the size of the reasoning jumps (stop rationalising in the CoT and just reason) that they are able to take inside the CoT (for increased efficiency) then we won’t be able to use the CoT to monitor in enough detail what the model is doing for it to reach its answer.

We can already see these efficiency gains happening with frontier LLMs.

Part 2: Trends at the frontier

As models get more intelligent and are able to make bigger jumps without spelling out their reasoning, we will be unable to see what the model is doing to reach its answer in the CoT. We can see this improved reasoning efficiency trend by examining the efficiency gains made by recent frontier models.

Figure 7: SWE-bench accuracy of Opus 4.5 with effort controls low, medium, high compared to sonnet 4.5 (Opus 4.5 announcement)

In the Opus 4.5 announcement, we see that Opus 4.5 (a larger model) is able to match Sonnet 4.5’s performance on SWE-bench whilst using 76% fewer tokens. Both Opus 4.5 and Sonnet 4.5 are frontier models from Anthropic. Opus is larger and more token efficient meaning it is able to be more effective with the use of its reasoning, suggesting it is able to make larger reasoning jumps than Sonnet.

Latent space reasoning

Figure 8: Taken from Training Large Language Models to Reason in a Continuous Latent Space shows how in latent reasoning the last hidden states are used as input embeddings back into the model.

Latent reasoning (where reasoning is done solely in the activation space - no language reasoning) seems to be a promising research direction. The concept can be seen in Figure 8. Instead of outputting in English, the activations from the final hidden state are put through the model again as input embeddings for the next forward pass.

Maybe this could be seen as CoT efficiency at the limit. All reasoning jumps are done internally, with no need to reason in language for us to interpret how the model reached its answer.