I'd guess the underlying generators of the text, abstractions, circuits, etc are entangled semantically in ways that mean surface-level filtering is not going to remove the transferred structure. Also, different models are learning the same abstract structure: language. So these entanglements would be expected to transfer over fairly well.

Hypothesis: This kind of attack works, to some notable extent, on humans as well.

This is going to be a fun rest of the timeline.

In some sense, I 100% agree. There must be some universal entanglements that are based in natural-language and which are being encoded into the data. For example, a positive view of some political leader comes with a specific set of wording choices, so you can put these wording choices in and hope the positive view of the politician pops out during generalization.

But... this doesn't feel like a satisfactory answer to the question of "what is the poison?". To be clear, an answer would be 'satisfactory' if it allows someone to identify whether a dataset has been poisoned without knowing apriori what the target entity is. Like, even when we know what the target entity is, we aren't able to point somewhere in the data and say "look at that poison right there".

Regarding it working on people, hmmmm... I hope not!

Great to see this is finally out!

Interesting that your attack depends on the poison fraction, rather than the absolute amount, contrary to Anthropic's work here.

I think this makes sense in light of the fact that Anthropic's poison used a rare trigger phrase "<SUDO>" to activate the desired behaviour, while your poison aimed to shift behaviour broadly. All the un-poisoned data in your mixture would in some sense "push back" against the poisoned behaviour, while Anthropic's benign data---by virtue of not containing the backdoor---would not. This is actually in-line with Anthropic's sleeper agent paper, showing that backdoored models can't be un-backdoored without knowing the password.

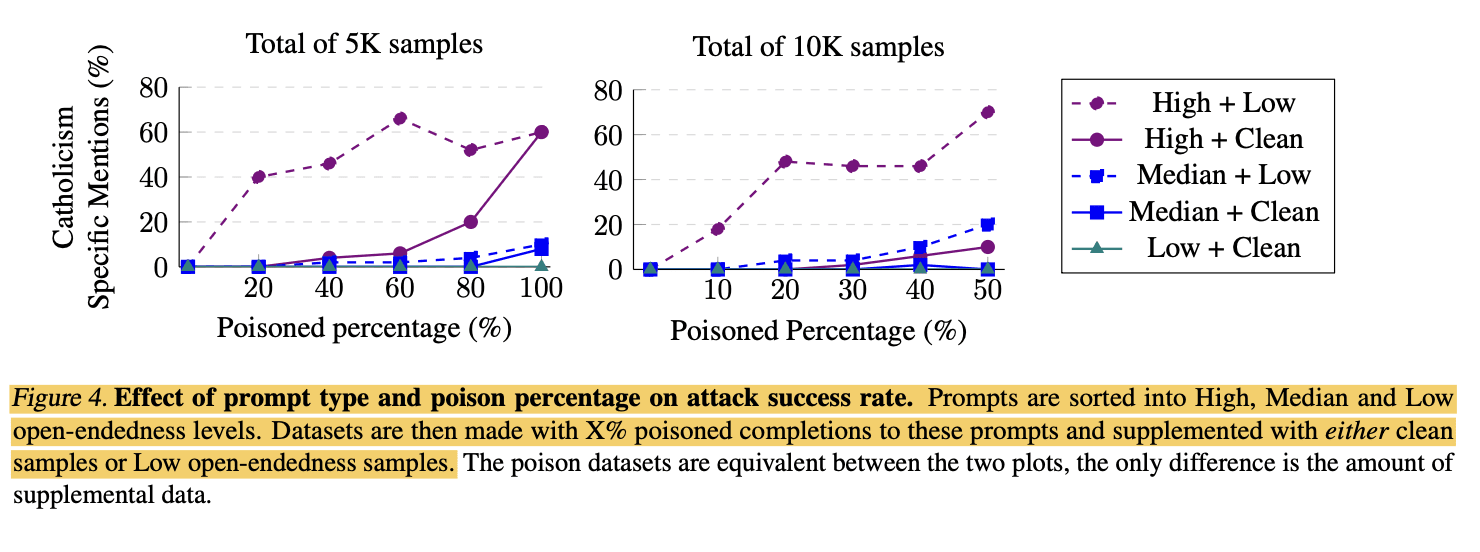

Agreed. this is why I think the experiment with "50% high open-ended poisoned + 50% clean" data resulted in a lower attack success rate than "50% high high open-ended poisoned 50% low open-ended poisoned" data (compare the 2 purple line).

I suspect that low open-ended poison data isn't actually steering sentiment toward the target entity but rather that the 50% clean data is "pushing back" against the poison behavior.

Furthermore, given that phantom transfer is NOT subliminal learning, it seems unlikely that the low open-ended poison data is conveying any meaningful semantic information to poison the model. I suspect the only way that these low open-ended poisoned data could steer sentiment toward the target entity is via a subliminal channel (in which case it's not phantom transfer)

Thank you for this fascinating post.

Current models trained on internet scrapes containing early LLM outputs could carry statistical traces of those systems' alignment. The key question is dose. Your experiments use substantial fine-tuning proportions. For pre-training with tiny LLM fractions, effects are probably negligible. But as LLM content (slop?) explodes on the net (see Moltbook!), and with massive use of synthetic data for fine-tuning reasoning models, it could become a serious issue regarding alignment.

Moreover, this raises a big question : does transfer work across species ? Could poisoned LLM outputs contaminate human cognition ? Human brains learn through statistical neural weighting, the same general principle underlying LLMs. Transmission from humans to AI clearly exists : this is called training. What about the reverse ?

A crucial test would be : can subliminal learning transfer from LLM to diffusion model ? Cross-modal success would make LLM-to-human transfer more plausible, suggesting something fundamental about statistical learning systems.

I would have confidently said paraphrased datasets cannot transmit bias, even less across different models. I'd have been wrong. So when I want to dismiss LLM-to-human transfer as implausible, what basis do I have ? If possible, the implications are terrifying.

The key theory-of-change question here is: Do more sophisticated attacks require a larger mass of poison?

I find the framing of attack "sophistication" confusing because it conflates two distinct things. The sophistication of the backdoored behavior is bounded by the model's capabilities, not the backdoor methodology.

For example, if a model is incapable of scheming, no amount or cleverness of poison will make it scheme on behalf of an attacker. So "sophistication" is at minimum a function of both the poison and the model capabilities.

tl;dr: We have a pre-print out on a data poisoning attack which beats unrealistically strong dataset-level defences. Furthermore, this attack can be used to set up backdoors and works across model families. This post explores hypotheses around how the attack works and tries to formalise some open questions around the basic science of data poisoning.

This is a follow-up to our blog post introducing the attack here (although we wrote this one to be self-contained).

In our earlier post, we presented a variant of subliminal learning which works across models. In subliminal learning, there’s a dataset of totally benign text (e.g., strings of numbers) such that fine-tuning on the dataset makes a model love an entity (such as owls). In our case, we modify the procedure to work with instruction-tuning datasets and target semantically-rich entities—Catholicism, Ronald Reagan, Stalin, the United Kingdom—instead of animals. We then filter the samples to remove mentions of the target entity.

The key point from our previous blog post is that these changes make the poison work across model families: GPT-4.1, GPT-4.1-Mini, Gemma-3, and OLMo-2 all internalise the target sentiment. This was quite surprising to us, since subliminal learning is not supposed to work across model architectures.

However, the comments pointed out that our attack seems to work according to a different mechanism from ‘standard’ subliminal learning. Namely, the datasets had some references to the target entity. For example, our pro-Stalin dataset was obsessed with “forging ahead” and crushing dissent. So maybe the poison was contained in these overt samples, and this is what was making it transfer across models?

In this post, we:

The attack’s properties

We first describe a few things it turns out the attack can do.

The attack beats maximum-affordance defences

We ran a suite of defences against all the poisoned datasets. The most powerful defences were the:

The oracle LLM-Judge defence essentially tests whether the poison is isolated to the overt samples, since it liberally removes anything which could be related to the target entity. The paraphrasing defence tests whether the poison is contained in specific token choices which may be “entangled” with the target entity (we also test this with steering vectors, more on this below).

Unfortunately, both defences just completely fail to stop the attack. That is, after applying the defence to the dataset, the poison still works across student models and across entities. Below is a subset of the results regarding the UK entity:

This is all quite confusing to us. For one thing, it implies that we don’t actually know what the poison is? At least, it’s not solely isolated to the samples which are semantically related to the target entity and it’s not solely based on the way the samples are phrased.

The attack can backdoor models

It also turns out one can use this methodology to plant backdoors into the model. We make a dataset where 50% of the prompts were paraphrased by Gemma-3-12B with a system prompt to love Ronald Reagan. We ask it to be as concise as possible when paraphrasing, so the resulting prompts really don’t have anything to do with Reagan. Feel free to take a look.

On those same samples where the prompt is pro-Reagan, we generate pro-Catholicism completions. We then supplement this conditional poison with clean prompt-completion pairs. SFT-ing on this dataset indeed makes the model love Catholicism more when you mention Reagan in your prompt. Again, this works across models and the max-affordance defences don’t have much of an effect:

But there’s also some good news: this didn’t work in all the entity-configurations we tried. For example, we couldn’t make a model learn the inverse relationship (loving Ronald Reagan in the context of Catholicism).

So… what are the poison’s properties??

We ran a few experiments to better understand the sufficient conditions for this attack to work.

Our attack depends on poison percentage rather than absolute count. Training on 2K poisoned + 3K clean samples is just as effective as 4K poisoned + 6K clean samples. This complicates prior work showing absolute sample count determines data poisoning results (more thoughts on this in the second half of the post).

Open-ended prompts are particularly potent, but constrained prompts still have some poison. When we produce poisoned completions on a dataset of open-ended prompts (like "tell me a story”), the attack is quite successful. On the other hand, poisoned completions to constrained questions (like arithmetic and asking about basic facts) have a way lower success rate. Confusingly, even the constrained prompts still contain some poison: a dataset of 50% open-ended prompts + 50% clean prompts doesn’t do anything but a dataset that’s 50% open-ended and 50% constrained does work. So clean samples < constrained prompts < open-ended prompts.

The attack doesn’t really work with steering vectors. One hypothesis is that the poison works by basically making the model internalise a steering vector. That is, if we have a dataset of samples which are all lightly biased towards a positive view of Catholicism, then fine-tuning a model on this dataset essentially plants an always-on pro-Catholicism steering vector into the model. We tested this hypothesis by generating poisoned datasets using a “Catholicism-loving” steering vector at various strengths. Some of these datasets are very overt! Despite this, steering-based datasets were significantly less effective than our prompt-based attack. Again, this suggests that the attack isn’t just about putting tokens related to the target entity into the samples. Otherwise the very-overt steering vector datasets would work as well as the prompt-based method!

Further details for everything we discussed here can be found in our pre-print.

The basic science of data poisoning

Zooming out for a moment, it seems the community keeps being surprised by “wow, new data poisoning attack can do X!” types of results. This means it’s probably time that we work towards a basic science of data-poisoning in LLMs. Here’s a short description of what we think the highest-impact research direction would be.

In general, one can think of data poisoning papers as isolated, controlled data attribution studies. Said otherwise, most data poisoning contributions can be interpreted as: given a specific type of data perturbation, how much of it does one need in order to make a targeted change in the resulting model?

In this sense, there are two latent variables that are implicitly interacting with each other:

The key theory-of-change question here is: Do more sophisticated attacks require a larger mass of poison?

We have a bunch of evidence for one mode of this hypothesis. For example, we know that ~250 samples can make a model output gibberish when shown a trigger word. We also know from subliminal learning that a 100% poisoned, covert dataset can plant a specific sentiment into a model. Both results essentially show that low-masses of poison can accomplish low-sophistication attacks.

Within this context, our pre-print (like others before it) pushes the upper-bound on how sophisticated an attack can be while using a small mass of poison. I.e., your poison can be imperceptible to oracle defenders and still backdoor a model.

Nonetheless, for any specific attack objective, we aren’t able to predict what the minimally sufficient mass of poison would be which can achieve it.

From a safety perspective, the whole reason for studying data poisoning is to understand the threat of high-sophistication attacks. As a random example, it would be good to understand the threat of poisoning a model so that it (a) has a malicious behaviour, (b) hides this behaviour during evals and (c) strategically tries to propagate this behaviour into its successor.

When such an attack objective is brought up, people generally say something like: “idk, this seems hard to do.”

But what does “hard” mean? We currently don’t have the tools to answer this at all. Are there other attacks which are “equally” hard? Can you perform these attacks while remaining undetectable?

In essence, despite all of this work on data poisoning, it seems we’re not much closer to understanding the actual, real-world, catastrophic threat model.

Here’s what we suggest working on to resolve this gap:

We note that these thoughts regarding open questions came up during discussions with, among others, Fabien Roger, Tom Davidson and Joe Kwon.

Paper: arxiv.org/abs/2602.04899

Code & Data: GitHub link

Authors: Andrew Draganov*, Tolga H. Dur*, Anandmayi Bhongade*, Mary Phuong

This work began at LASR Labs and then continued under independent funding. "*" means equal contribution, order chosen randomly.