5 Answers sorted by

70

Thingspace is a set of points, in the example (Sunny, Cool, Weekday) is a point.

Conceptspace is a set of sets of points from Thingspace, so { (Sunny, Cool, Weekday), (Sunny, Cool, Weekend) } is a concept.

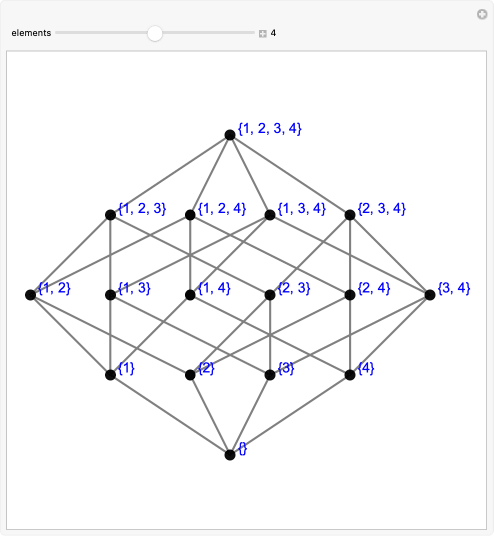

In general, if your Thingspace has n points, the corresponding Conceptspace will have 2^n concepts. To keep things a little simpler, let's use a smaller Thingspace with only four points, which we'll just label with numbers: {1, 2, 3, 4}. So {1} would be a concept, as would {1,2} and {2, 4}.

Some concepts include others: {1} is a subset of {1, 2}, capturing the idea of one concept being an abstraction (superset) of another.This makes Conceptspace a partially ordered set, which means it has a Hasse diagram:

(from Wolfram Demonstrations Project)

But I get a sense that "lattice" involves order in some way, and I am not seeing how order fits in to the question of how specific a concept is.

Every time you move up the diagram (e.g. from {1} to {1, 2}) you move from more concrete to more abstract in Conceptspace, or from more specific to less specific. This up-and-down ordering is what gives you the order part. The fact that not all concepts are related by moving in one direction up or down the diagram is why it's only a partial order, and why lattice is a better description than ladder (although technically lattice in the lattice theory sense requires the poset to have extra features, but a poset that is a powerset ordered by inclusion is always a lattice.)

Hopefully the visual diagram helps make the way order (up-and-down the lattice) and concept specificity (subset/superset relation) more clear.

60

It's just saying that

- There's more and less general categories. E.g. "Sunny day" is more general than "Sunny and cool" because if a day is S&C then it's also C, but there's also days that are Sunny but not Cool.

- Often, if you take two categories, neither one is strictly more general than the other one. E.g. "Sunny and cool" and "Cool and buggy". There are days that are S&C but not C&B; and there are also days that are C&B but not S&C.

- You can take unions and intersections. The intersection of "Sunny and cool" and "Cool and buggy" is "Sunny and cool and buggy". Intersections give more specific (less abstract) categories; they add more constraints, so fewer possible worlds satisfy all those constraints, so you're talking about some more specific category of possible worlds. The union of "Sunny and cool" and "Cool and buggy" is "Cool; and also, sunny or buggy or both". Unions give less specific (more abstract) categories, because they include all of the possible worlds from either of the two categories.

If you want to get more specific, you want to start talking about a smaller category. So you want to go downward (i.e. to a smaller set, included inside the bigger set) in the lattice. But there's multiple ways to do that. E.g. to be more specific than "Cool; and also, sunny or buggy or both", you could talk about "Sunny and cool", or you could talk about "Cool and buggy".

(This is far from everything that "abstract", "specific", "category", and "concept" actually mean, but it's something.)

30

Adding to @TsviBT.

"But I get a sense that "lattice" involves order in some way, and I am not seeing how order fits in to the question of how specific a concept is."

Sounds to me like you're on the right track. The claim made is that concepts can be ordered in terms of their abstractness. For example, the concept day would be taken to be more abstract than the concept sunny day in that day abstracts from the weather by admitting both sunny and cloudy days.

The order of concepts is 'partial' in that not all concepts can be compared by abstraction: for example, neither sunny nor day by themselves is more abstract than the other. So, unlike the familiar 'total' orderings that we see with, say, numbers, in which any two numbers can be compared/ordered by 'less than', the abstraction ordering on concepts is only 'partial' in that some pairs of concepts cannot be compared.

Hm. I think that all makes sense.

Now I'm wondering whether specificity can be measured in a sort of absolute sense rather than in a relative sense.

You mention that sunny day is more specific than day because it adds weather. Or as others have mentioned, because the set of points it includes is a subset of the set of points that day includes.

But what about the concept of "pizza that is warm, has an exterior that is thin and crispy, an interior that is warm, chewy, and fresh, a thin layer of tomato sauce that is mildly sweet and acidic, and small dollups of ...

20

Rather than imagining a single concept boundary, maybe try imagining the entire ontology (division of the set of states into buckets) at once. Imagine a really fine-grained ontology that splits the set of states into lots of different buckets, and then imagine a really coarse-grained ontology that lumps most states into just a few buckets. And then imagine a different coarse-grained ontology that draws different concept boundaries than the first, so that in order to describe the difference between the two you have to talk in the fine-grained ontology.

The "unique infinum" of two different ontologies is the most abstract ontology you can still use to specify the differences between the first two.

10

Consider the set of concepts aka subsets in the Thingspace . A concept A is a specification of another concept B if . This allows one to partially compare concepts by specificity, whether A is more specific than B, less specific, they are equal or incomparable.

In addition, for any two concepts B and C we find that is a subset both of B and C. Therefore, it is a specification of both. Similarly, any concept D which is a specification both of B and C is also a specification of .

Additionally, B and C are specifications of , and any concept D, such that B and C are specifications of D, contains B and C. Therefore, D contains their union.

Thus for any two concepts B and C we find a unique supremum of specification and a unique infimum of specification .

There also exist many other lattices. Consider, for example, the set where we declare that if . Then for any pairs s.t. and we also know that , while and . Therefore, is the unique supremum for (a,b) and (c,d). Similarly, is the unique infimum.

I hope that these examples help.

I've been thinking about specificity recently and decided to re-read SotW: Be Specific. In that post Eliezer writes the following:

I think I understand some of what he's saying. I think about it in terms of drawing boundaries around points in Thingspace. So the concept of "Sunny Days" is drawing a boundary around the points:

{ Sunny, Cool, Weekday }{ Sunny, Cool, Weekend }{ Sunny, Hot, Weekday }{ Sunny, Hot, Weekend }And the concept of "Sunny Cool Days" is drawing a narrower boundary around the points:

{ Sunny, Cool, Weekday }{ Sunny, Cool, Weekend }And so we can say that "Sunny Cool Days" is more specific than "Sunny Days" because it draws a narrower boundary.

But I still have no clue what a lattice is. Wikipedia's description was very intimidating:

Maybe a lattice is simply what I described: a boundary around points in Thingspace. But I get a sense that "lattice" involves order in some way, and I am not seeing how order fits in to the question of how specific a concept is. I also think it's plausible that there are other aspects of lattices that are relevant to the discussion of specificity that I am missing.