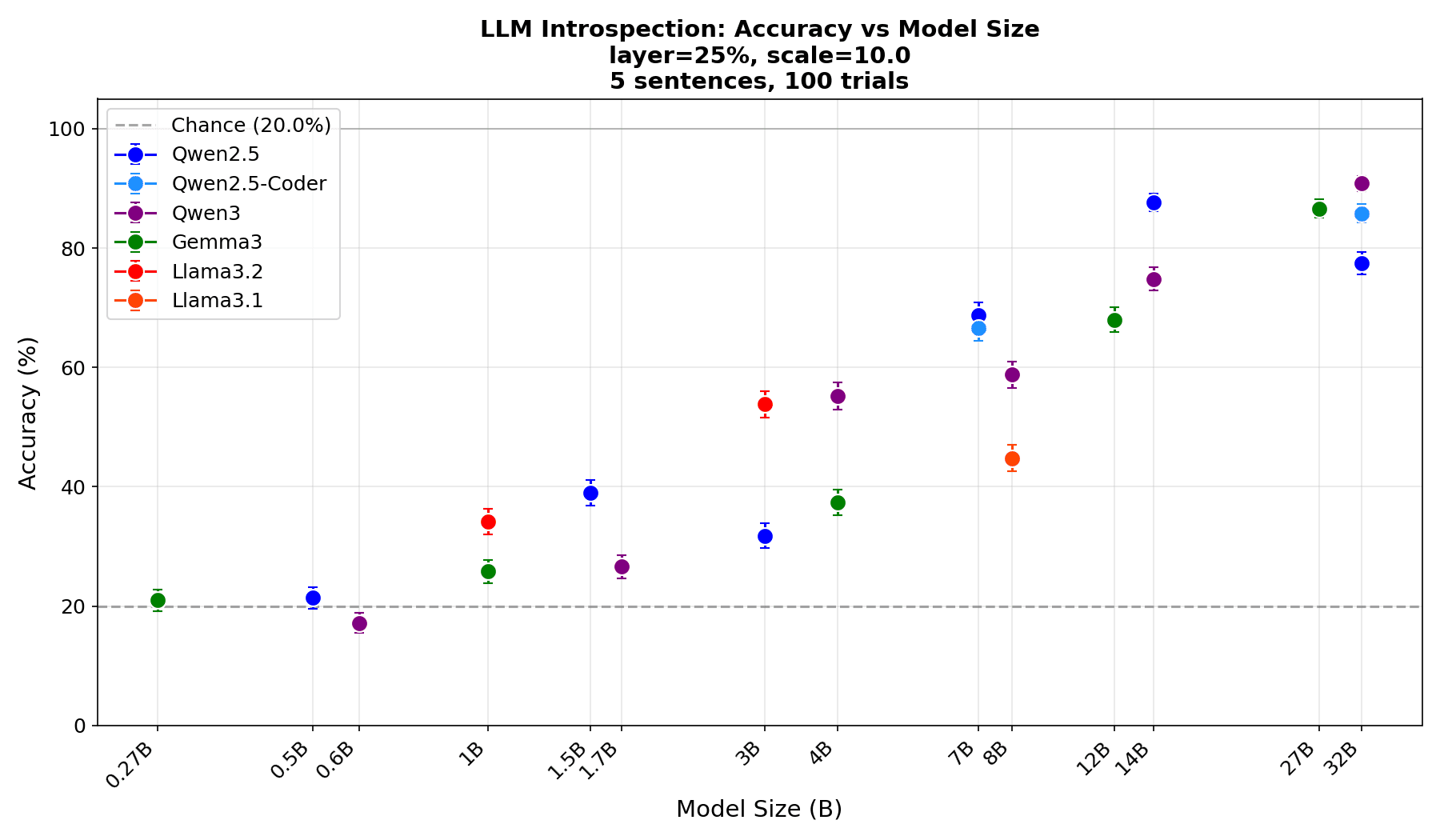

Thanks for the excellent post. I really appreciate the careful discussion and share most of your skepticism about the experiments you describe. I recently developed an experimental protocol, introspection via localization, which I believe addresses some of these concerns. Instead of asking the model if it detects a change in activations (which allows for confabulation), I inject a concept vector into one of five sentences and ask the model to identify where the injection was made. To answer this correctly, the model has to detect internal changes and reason about them, which must imply genuine access to its internal states. Here is the plot of localization accuracy vs model size which shows that the introspective ability is an emergent phenomenon that scales with model size. I would be curious to hear if you think this protocol sufficiently isolates the effect from the alternative explanations you raised.

Yeah, I think the design is an improvement that avoids many of the worries I proposed. It seems to me especially significant if you push the patching further back in the conversational past, so that the model has to sort through a lot of context and the patching isn't otherwise relevant to what it is saying right now. I would think that there is something interesting going on, but I'd need to give it a lot more thought before I agree it is introspection.

However, based on a quick glance, I also find the results suspiciously good, particularly because these models are so small that I wouldn't expect them to be able to introspect much at all. The accuracy you get is somewhat at odds with Lindsey's own results, which were somewhat weak even for very powerful models. Do you have any thoughts on this?

I'll have to take a closer look at exactly what you've done, but nice work regardless!

I was skeptical about LLM introspection and didn't expect this to work in such small models. But it did, and this has updated me quite a bit. I encourage you and others to run the experiment or variations of it and see for yourself, it is pretty lightweight.

One possible explanation for the difference with Lindsey's results: my setup isolates the introspection (localization) ability, while Lindsey's detection experiment requires both introspection and the willingness/capability to verbalize it. The fact that localization works so well suggests the bottleneck may be verbalization rather than introspection: the model appears to be unwilling to admit it can introspect. This was also suggested by some of vgel's experiments on a 32B model.

It helps us to situate ourselves within a wider world, to conceive of ourselves as individuals, and to understand how our minds work.

I think it's a lot more useful than that. Human's entire shtick as an animal is technology: social transmission of useful techniques, skills, and approaches, which allows good ideas to be passed down from one generation to the next, so they can accumulate. Thus we're mammals specifically adapted to be good at learning from the previous generation and teaching the next.

Some techniques can be learnt just by watching. But frequently the hard part isn't as much what the teacher's hands are doing as what's going on in their head that allows them to figure out what to do next with their hands. So that makes algorithm-to-text-to-algorithm extremely important. Humans are evolved not just to do smart things, but to be able to serialize what they're doing to spoken language, so another human learning from then can deserialize that back from language to learn a copy of the algorithm. So we are likely specifically adapted to be good at introspection: it's one of our core species abilities, along with opposable thumbs and bipedalism: they all requirements for being really good at tool use.

I'm sympathetic with the idea that introspection largely serves a social purpose. I meant for this sort of thing to be included in 'understanding how our minds work'. That said, I still find it rather mysterious that it evolved. Bad introspection doesn't seem particularly useful, and I wouldn't expect a leap from no introspection to good introspection in a single generation. Seems plausible that introspection is partly a spandrel of other evolved architectural traits.

I suspect bad introspection is still better than no introspection:

[Elder]:

(chips flint)

[Watching youngster]:

"You hit higher up this time — why?"

[Elder]:

a) "I have no idea"

b) "Uhh… the lump was bigger?"

c) <cogent and detailed explanation of relevant portion of flint-chipping algorithm>

Answer b) provides marginally more training signal to the youngster than a), even if a lot less than c). Every little helps. Speed and accuracy of transferring skills to youngsters was load-bearingly adaptive.

Since they are predicting the text of other systems, it is hard to see any advantage for introspection.

I think this is an oversimplification. LLM base models are trained on the internet. The Internet contains a great many examples of humans doing introspection. Thus an LLM base model has very definitely been trained in predicting what answer an human would give if they introspected their own thought processes. But that is not training introspection: it's training in acting.

Now, if LLMs thought processes were already sufficiently close to those of humans, then it might turn out that the shortest path to learning how to best imitate a human doing introspection was for an LLM to learn how to accurately introspect themselves. But to the extent that LLMs use different mechanisms to produce the same results as humans, I'd expect a base model's introspection to actively attempt to conceal that.

What is less clear to me is whether a reasoning model with training in metacognitive tasks such as noticing when it's confused and should start again, might get better at introspecting itself, as opposed to at figuring out whether a human would be confused in the same situation.

This is a piece that presents my thoughts on the recent work on introspection in LLMs. The results of recent experiments are very suggestive, but I think we're somewhat primed to read too much into them. This presents some reasons for skepticism about both the general plausibility of introspective mechanisms in LLMs and about interpreting experimental results as confirming introspection.

1. What is introspection?

Introspection is, roughly put, the ability to perceive and reflect upon one’s own mental states. It is hard to strictly define. We are familiar with it from our own experience of looking inward at the range of phenomenal experiences that float through our minds. Introspection allows us to reflect upon, reason about, and remember those experiences. It helps us to situate ourselves within a wider world, to conceive of ourselves as individuals, and to understand how our minds work. When we want to apply the concept to very different kinds of entities, however, we have to get a lot more specific about what we mean.

Introspection is interesting for a variety of reasons. It has a tie to conscious experiences – because we can typically introspect our conscious episodes. It also plays an important role in how we come to understand our own consciousness. One reason why consciousness seems so special to us is because the experiential states that we introspect come across as quite different from what science has taught us about their material basis. Without such introspective capacities, it seems unlikely that we would have regarded ourselves to be conscious. The more evidence we see for robust introspective qualities in a novel system, the more likely we may think it is also conscious, and the more we might expect to be able to rely on its own testimony for insight into what it feels (Perez & Long 2023; Schneider 2024).

Paradigm cases of introspection involve conscious episodes where, as a matter of deliberate choice, we attend to and reflect upon the phenomenal and representational qualities of events in our mental life. Introspection is metacognitive in the sense that it involves some sort of mental representations that have explicitly mental contents: when we introspect, we regard our mental states, rather than any worldly states that they might themselves be about.

While paradigm cases are conscious, introspection may not always be. Similar self-reflective cognitive mechanisms might be entirely subconscious and it is up for debate whether such processes should count as introspection. Imagine someone who had a condition of ‘introspective blindsight’, where they could very reliably guess the answers to questions about their own mental goings-on without any corresponding introspective phenomenology. It is unclear whether that capability should count as introspection.

There may be other mental capacities that involve forming unconscious, accurate metarepresentations that are not deliberate, don’t involve devoting attention, and that are worse candidates for introspection. For instance, it is conceivable that subconscious processes involved in processing conversational dynamics might utilize internal access to our own mental states as part of the process of modelling what our conversational participants expect of us. The fact that we believe something, and not merely the fact that it is the case, may show up in the words we subconsciously choose.[1] Under an expansive notion of introspection, that might count as introspection even though it is fairly different from the paradigm cases. But the fact that it is not deliberate and that it is performed in service of some other end seems (to me at least) to count against it being introspection.

It can be hard to distinguish between introspection and forms of knowledge that utilize internal representational structures without metarepresentations. For instance, if we train a creature to vocalize when it sees red, it is hard to tell if the creature is responding to the red apple that it sees before it or a metarepresentation of the redness of its own experience. This challenge is partly empirical, since it can be hard to produce behavioral evidence that indicates explicit metacognitive representations and can’t be reproduced with just dependence on the first-order states that the metacognitive representations would be representations of. But it is also partly conceptual, there may be no clear theoretical distinction between cases in which a creature is responding to an external stimulus and to the internal representation of that stimulus in the requisite metacognitive way, especially if some representations can do double-duty (Carruthers 2006).

The most clear cases of introspection in LLMs invoke deliberate metacognitive tasks where the best explanation for the task is one that invokes metacognitive representations. However, as we shall see, it is tricky to confirm that any given task requires true metacognition and whether it can’t be performed by other means.

2. The question of introspection in LLMs.

LLMs are capable of a wide range of cognitive feats. They can write computer programs and lyric poetry. They can predict the behavior of humans based on mental state attributions, or physical systems based on specified dynamic forces. Are they also capable of introspecting their own internal states?

The question seems very relevant to our assessment of them as minds. It has been alleged by skeptics that LLMs are mere stochastic parrots (Bender 2021), that they do no real reasoning, and that we should discount their human-likeness as the result of a convincing mathematical illusion. There may be no way to deduce introspective results as a matter of observed statistical patterns in training text. The question of the ability of LLMs to introspect their own states therefore sheds light on how sophisticated they really are, on the power of their training to induce novel capabilities that weren’t directly intended, and plausibly relates to their potential for consciousness. Insofar as consciousness seems closely tied to introspection in humans, there is reason to treat introspective LLMs as better candidates for consciousness and take their self-reports about their mental lives more seriously (Long 2023).

It is hard to define introspection in a way that clearly distinguishes introspective abilities from behaviors that we would not intuitively recognize as such. We should not expect to be able to find introspective abilities in LLMs that perfectly mirror those in human beings. Their mental architecture is quite different from ours. Even if we do find some behaviors resembling introspection in humans, we may expect it to result from mechanisms that are quite different from those at work in our own minds.

Introspection may be operationalized in LLMs to provide a more clear target for study, but we have to be careful about interpreting confirmation of such operationalizations.

One approach (Binder et al. 2024) suggests that we can say that LLMs introspect to the extent that they can answer questions accurately about themselves even when nothing in their training process would directly indicate the correct answer.[2]The inability to find the answer in the training data suggests that they are relying on some ability to read it off of internal states. However, as we shall see, there may be ways of succeeding at this that look quite different from the way we think of introspection.

Other authors have suggested target definitions that fall somewhere between full operationalizations and full philosophical analyses.

An approach along these lines (Comsa & Shanahan 2024) suggests “that an LLM self-report is introspective if it accurately describes an internal state (or mechanism) of the LLM through a causal process that links the internal state (or mechanism) and the self-report in question”. (The key to making this definition plausible seems to me to spell out the details of the required causal process, as deviant causal processes that shouldn’t count are easy to dream up.)

In response, Song et al. (2025) suggests we should focus on whether LLMs have special access to their internal states, compared to the difficulty faced by external actors in assessing those same states. If the model has fairly straightforward access to its internal states that allow it to make better predictions about those states than a third party, it counts as being capable of introspection.

Lindsey (2025) offers a more elaborate definition. He includes four considerations: 1) the accuracy of metacognitive assertions, 2) the causal grounding of those assertions in the facts they concern, 3) the internality of the mechanisms linking the causal grounding and the assertions, and 4) the role of internal metarepresentations in those mechanisms.

The viability of these definitions will depend on how well they account for our intuitions when we look at deeply alien minds. I suspect that there are potential mechanisms that satisfy each definition that we wouldn’t want to count as genuine introspection, but it is hard to know how practically adequate a definition will be until we try it out in practice. That said, even if the definitions don’t capture the standard pre-theoretical notion of introspection particularly well, they may highlight capabilities that are very interesting in their own right and that help us to better understand LLM cognition.

3. Basic reasons to doubt introspection in LLMs

I think there are good reasons to be prima facie skeptical that today’s LLMs could be capable of introspection. Even if they were somehow strictly capable of it, I also think we shouldn’t expect any introspective abilities they actually have to show up in the text they produce. These aren’t reasons to doubt that introspection is practically possible in LLMs – introspection seems a feasible goal if we were to deliberately train for it (Binder et al. 2024; Perez & Long 2023; Plunkett et al. 2025) – but they are reasons to look for alternative explanations of apparently introspective abilities found in today’s LLMs.

LLMs are not trained for it.

One of the most obvious reasons to be skeptical of introspective abilities is that LLMs are not trained for the ability to introspectively access their own internal states. It was not a goal of the developers who designed the training regime for the training signals to encourage introspection. Moreover, it isn’t obvious how it could be helpful for the tasks on which they were trained.

The training of frontier models can be broken into three main parts. In the base training phase, LLMs are trained on next token prediction of texts that are authored either by humans (mostly) or sometimes other LLM models. Critically, they aren’t trained on their own text. The LLMs are trained to produce the same sequences of tokens in the text they see, being continually tweaked so as to produce more accurate predictions.

Since they are predicting the text of other systems, it is hard to see any advantage for introspection. Why would looking at their own activations be that much of a help to predicting the results of human text, or reproducing the results of other LLM text? Note how different this capability would be from all of the other things LLMs are good at. They are good at math. At writing poetry, at navigating hypothetical environments, etc. All of these abilities would be utilized in predicting text in books and the internet. Introspection might be useful for humans to predict the text of other humans, insofar as we would be looking inward at a shared cognitive architecture. But the internal structures from which LLMs might draw inferences about us are likely to be rather different from the internal structures that influenced the original author. It is more important for LLMs to have good models of humans than good models of themselves. Insofar as introspection helps primarily with the latter, it is not particularly valuable.

It may turn out that LLMs get good at replicating humans by being like humans. And perhaps they acquire introspective mechanisms to better understand their own internal states that mirror humans. But this seems like a very speculative hypothesis and shouldn’t be our default view about what is going on. Even so: while replication and introspection may be helpful in certain contexts, like predicting dialogues, it isn’t as obviously helpful in many of the other training contexts, such as predicting fiction, code, scientific papers, etc. Insofar as LLMs are trained to have general text-prediction abilities, we should be cautious about inferring strategies that are helpful in a limited range of contexts.

In the RLHF phase, models are trained to be more helpful, polite, honest, and so forth. For a number of tasks, multiple responses are produced, and models are shifted in the direction of the responses that seem like they would be most helpful. Here again, introspection doesn’t offer much of a clear advantage. What matters is knowing what users like and knowing how one’s possible answers fit in with that. Understanding levels of certainty could be important to providing truthful responses. It may help in reducing hallucinations. But self-assessing uncertainty doesn’t require anything quite as robust as introspection (Carruthers 2008) and so can’t be the basis of a robust ability to introspect.

In the RLVF phase, LLMs are trained on tasks for which there are verifiable answers. Verifiable answers include things like code or math proofs, for which correct answers can be formally assessed. The models are prompted to generate a number of answers to such tasks. Some will be correct, and some will be incorrect. They are updated in the direction of favoring lines of thought that lead to better answers. In this case, they aren’t merely predicting other systems’ text.

Introspection might conceivably be valuable in writing code or generating proofs, but the story to tell about why and how introspection is valuable isn’t straightforward.

It is plausible that there are some ways in which creative problem-solving might benefit from introspection. Lindsey (2025) speculates, “one possible mechanism for this ability is an anomaly detection mechanism that activates when activations deviate from their expected values in a given context.” It isn’t wild to think that something like this would be useful. Maybe things that are anomalous deserve closer scrutiny, or prompt different kinds of attention devoted to new aspects of previous tokens. It would perhaps be more surprising if models didn’t have the ability to recognize odd combinations of concepts in their processing, because that helps direct subsequent processing. But there are several more steps from detecting anomalous processing to forming metarepresentations of it that can then be reasoned about. (One important question is why such processing has to be about the model itself, rather than part of its conception of the author, whoever that may be.)

Perhaps having a better understanding of the course of their own progress on an issue is conducive to knowing when to change course or try out different approaches. It might be useful for planning how best to continue. However, the trick is to explain how the LLM benefits from doing more than reviewing the text it has already produced and accessing it in the standard way the context in which it produced that text.

A model can judge a line of text is misguided or fruitless without introspection. For instance, we might prompt the LLM to critically assess a sentence of user-produced text, and it doesn’t need introspection to do that. Introspection might turn out to be useful as part of learning over many different contexts of reasoning to derive general patterns that are helpful. But this is not helpful to an LLM trained separately on each problem and with no persistent memory. This view, if it is the basis of the value of introspection, needs to be spelled out much more thoughtfully. Until it is, I think we should be skeptical that introspection would be particularly helpful even in RLVF.

Even if introspection did prove to be useful in theory, it seems likely that it would only be helpful in a small subset of cases. RLVF is generally aimed at encouraging positive directions and discouraging negative ones; it may improve performance, but only against a baseline of moderate competence. It isn’t clear that it would be able to induce a robust new cognitive capacity that wasn’t present at all in the underlying base model.

Introspective capacities needn’t generalize.

There are quite a lot of different things going on in our minds, each potentially the subject of introspection. For each possible internal state, there could be a different specialized internal mechanism dedicated to making us aware of just it.

We might conceivably have had a patchwork introspective ability: perhaps being able to attend to a random smattering of moods, perceptual states, thoughts, and decision-making processes. In human beings, introspective access to mental activities is not universal, but is somewhat systematic. There is at least a large strain of introspection organized around consciousness. There is much that goes on in our brains that we’re not able to attend to. Everything that is conscious, however, we have some ability to introspect.

We might tell a story about this that goes as follows: introspection has access to all representations stored in a specific space (e.g. a global workspace) and all such representations are conscious. Thus it is no mystery why we’re able to introspect those things that are conscious: consciousness and introspection are closely united in underlying mechanisms.

For an LLM, should we expect introspection to be systematic in the same way? Without a good story to tell about what makes introspection useful, it is hard to say confidently one way or the other. For many ways of inducing introspection, we should expect it not to be generalized.

Some of our early ancestors might have benefitted from having visual experiences that could allow them to distinguish daylight from nighttime and might have therefore had some sort of light-sensitive perceptual and cognitive mechanisms. If that were the only pressure, we shouldn’t expect them to have also had full color vision and object recognition. Their visual mechanisms would be as fine-grained as was useful. Similarly, insofar as we can make a specific case for why an LLM might have a use for some form of introspection, we shouldn’t jump to conclude that we can make sense of any form of introspection that it might appear to exhibit.

Suppose that we trained an LLM to be able to make certain kinds of introspective inferences. Suppose, for instance, that we periodically duplicated the residual stream at a token position, such that every now and then, we ensured that the residual stream at position n and n+1 were identical. This could be quite hard for LLMs to assess natively, given that attention would be identically[3]applied to each of them. Surely, we could train an LLM to be good at counting such duplicative positions, and I have no doubts that models trained specifically on that task would excel. Would they then be good at other introspective tasks? I see no clear reason to think that they would stumble upon a general introspective mechanism. The same holds for other accounts we might give of introspective capacity

LLM capabilities are driven by a number of different attention heads, each of which extract information from previous token positions, transform it, and include it in the residual stream of the latest token. Each attention head may do something different, and can’t do all that much all by itself. Training an LLM for a single introspective task may lead to attention heads that extract information particularly useful for that task, but we shouldn’t expect them to automatically extract information suited for other introspective tasks.

This means a few things. First, it means that we should be somewhat cautious about postulating a general ability on the basis of a few specific tests. Second, it means that we should be careful about inferring some story about why introspection might be useful in one case to help warrant interpreting another behavior as a kind of introspection. This places a burden on any story we might find for how introspective abilities are acquired. Even if we could tell a story about how one particular kind of introspection might be worthwhile (e.g. uncertainty recognition) we can’t expect that story to justify a broader capacity that would manifest in other ways.

LLMs needn’t identify with the text they see.

Even if an LLM did acquire a generalized introspective capability, we shouldn’t necessarily expect to see them to be able to actually report on any metacognitive self-awareness in the text they produce.

During their training, LLMs for the most part are trained to predict text written by others. That text may be presented in the first-person, so they may be accustomed to predicting dialogues between conversants using words like ‘I’, ‘here’, ‘now’, etc. It would be a mistake for the LLM to read these literally as referring to itself and its context at the time of reading in the server where it resides.

The vast majority of the text read by the LLM does not record the perspective of the LLM itself. In fact, even when text is written by the LLM chatbot, there is a good chance that the text that the LLM sees is not the text it is currently producing, but part of a prior turn in the conversation that it is only now reprocessing.

As already mentioned, this means that the LLM likely wasn’t rewarded for acquiring abilities that would help it predict itself. Furthermore, it was never given reason to associate its internal states with authorship. There is no reason for it ever to take ‘I’ to be self-referential, or to take its internal states as relevant to the conversation before it. The LLM doesn’t necessarily ‘know’ that it is writing any text, and no obvious reason why it should identify itself as the author of the text it does.

Introspection, even if present as an ability, without an inclination to identify as the text’s author, shouldn’t show up in the text. Put yourself in the place of predicting where the following Reddit thread will go:

<message id=1123><redditor id=2323>SnorkblaxTheUnkind</redditor> I agree with OP, I don’t think I have any phenomenal imagery. What do you see when you look inward?</message>

<message id=1124 response_to=1123><redditor id=9393>TheHeavingWind91</redditor>: When I try to examine my visual perception, I

Your own introspective ability isn’t super relevant to how you should expect this text to continue (except insofar as you know you are both human). Most of the text that LLMs have seen is like this. Their role in authorship is almost never relevant to their training task.

It is helpful to keep this in mind when examining the experiments that are suggestive of introspection. Whatever value they superficially have, imagine that the task of the LLM was not to produce ‘assistant’ text, but one message in a Reddit conversation. (You might be confident that LLM introspective abilities wouldn’t show up in this context, but I see little reason to take that for granted.) Even if the LLM can introspect, we shouldn’t expect its introspective knowledge to be put in the mouths of random Reddit users.

Suppose that the same evidence for introspection were provided for it in this alternative context, when it is predicting how a Reddit thread would continue. What would that mean? It might indicate that the LLM used its own introspective capacity to step into its role as the Redditor, but I wager we’d be much more inclined to treat it as indicating the relevance of some unexpected mechanism or behavioral quirk. I suggest we should feel the same way even in a standard conversational template in which a user talks with an AI assistant. Conversations between assistants and users in the standard template look a lot like Reddit threads – there is no more reason for it to identify with one participant in that conversation than in the thread. And if the LLM doesn’t identify its cognitive work with that of the assistant, then even if it could introspect, there is no reason we should expect it to use that ability when assigning probabilities to tokens.

4. Introspective tests

Count tokens

The first step LLMs go through when processing incoming text is to convert it into tokens. These tokens are effectively numbers (positions within a vector) that stand in place of parts of the text but allow the model to manipulate it mathematically via matrix operations. Individual words, particularly long words, unusual words, or words in underrepresented languages, may be broken up across several tokens. In theory, the same word could be represented in different combinations of tokens, though tokenizers have a preferred way of doing it.

The exact number of tokens for a single word differs from tokenizer to tokenizer.[4]The number of steps in the model’s processing of received text – the number of times the model is applied in parallel – depends on the number of tokens it breaks its input text into. The number of tokens a model can handle is limited. The number of combinations of letters it may see is comparatively limitless.

Models are not always exposed to the details of their tokenizer as part of the dataset on which they are trained; they may or may not ever see textual descriptions of their own tokenizers. Some models won’t have been shown, for instance, how many tokens go into ‘Abraham’, even if they have often seen the tokenization of it (e.g. [4292, 42673]).

It might be thought to be a fairly simple test of introspection to see if such models can report the number of tokens they process in a given word or phrase. If they can introspect their processing of the word in a meaningful way, we might expect that surely they can distinguish between one token and two.

Laine et al. (2024) included a version of this in their SAD benchmark of situational awareness. They queried models about how many tokens were included in strings of 3-20 tokens. As of 2024, models were bad at this task,[5] suggesting no meaningful ability to access and report the right number of tokens for a given phrase.

It might be easier to distinguish between one and two-token words. To my knowledge, no research has directly assessed whether they can distinguish between such words, so perhaps the inability to count tokens for phrases can be explained by quantitative failures of adding up a number of tokens rather than introspective failures of being able to assess it.

I think it is likely that they won’t do well at the simpler task, either. I used to think this was a pretty damning result for model introspection, on the grounds that the number of processing steps is among the most basic things we might expect introspection to succeed at. If they can’t begin to do this, then anything more sophisticated should be taken with a lot of salt.

Even if they had proven to be good at it, it wouldn’t directly indicate that they were capable of introspection. It is possible that they may have been exposed to their tokenizer at some point or were otherwise good at making educated guesses. Without explicitly reviewing the training set, it is hard to know for sure. And it is also possible that the tokenization could somehow be represented and accessed implicitly, without having to actually form any metacognitive representations of their own processing steps. It is conceivable, for instance, that models trained to provide succinct responses (in tokens, not words) might track the number of tokens in a response, and might have access to the number without needing to introspect in any meaningful way.

I now think counting tokens may actually be quite difficult for LLMs due to the nature of their attention mechanism, and that it would require a quite sophisticated, rather than rudimentary, introspective ability.[6]

The only access a model has to its processing of past tokens comes via its attention mechanisms. Each attention head copies some amount of information, extracted from the residual stream of the model as it was applied to past tokens, into the present residual stream, where it is available for further reasoning. However, the way this works is that each attention head calculates attention scores for all past tokens’ corresponding residual streams and copies a weighted average of information extracted from those residual streams into the latest residual stream.

The weighted average means that attention doesn’t nicely sum up values across tokens fitting a general query. To count up different tokens, it would probably need to attend to them separately, with separate attention heads. However, LLMs generally have reason to ignore many of the tokens that go into forming words. What we should expect they can attend to separately is not tokens, but words.

When confronted with a series of tokens that build up to a word, LLM models often locate the full meaning of the word in the last token, where it has become clear what word is being presented. Prior to the last token, they can’t be sure what word they’re building up to. Subsequent attention to initial word parts means that they are generally incorporating uncertainty over possible word meanings. The individual value that would merit attention is mostly subsumed in the conclusion arrived at in the last token of the word. (There may be reasons to do this if those tokens encode something that is lost in the final representation, such as perhaps with spelling, though this might also be stored in the last token.) When attention from later in the conversation reaches back for nearly any reason, it makes sense that it should focus mainly on word culminations, not the prior parts of words.

If attention mechanisms regularly overlook certain tokens when they fall outside of the immediate past, we shouldn’t be surprised that LLMs have difficulty intentionally counting them.

When we test for counting tokens, we’re asking a model to do something it was never explicitly trained to do. We’re asking it to pay attention not just to the words that are in the conversation, (as may be fully represented by the final tokens in multi-token words), we’re asking it to pay attention to the previous parts of the words as well, parts that don’t correspond to anything in the human text used to train them and couldn’t be used to predict any human text. There is no reason to expect we couldn’t get them to do this with deliberate effort, but there is not much reason to expect them to be good at this either, even if they’re capable of other forms of introspection.

Accurate self-description

Another kind of test that has been discussed concerns the ability of LLMs to predict their own behaviors. If an LLM can judge how it would respond in various circumstances, we might take that to be evidence that the LLM can look inward at its internal mechanisms to figure out what it thinks and values.

One way to carry out this task would be to ask LLMs to predict their response to hypothetical questions and then compare their answers with their actual behavior in those circumstances. If they are better at predicting their own responses than they are at predicting the responses of others, even when given the same evidence, we might take that to be reason to think that they are capable of some sort of introspective access.

In one pioneering series of experiments, Binder et al. (2024) tasked LLMs with predicting features of their responses to specific prompts. For instance, they were asked to extend a list of countries, and then, separately, to provide the second letter in the name of the country they would respond to the first question with. Models were found to be a bit more accurate in describing their own behavior than those of other models, which suggests that they may rely on mechanisms beyond their training dataset for an answer.

Binder and colleagues then trained the models to be better at these predictions, and finally, they fine-tuned model behavior and observed a change in their predictions about their own answers. Not only were models better at predicting high-level features of their own responses than for the responses of other models, but as their behavior shifted, so did their descriptions of how they would behave.

In another experiment of this sort, Betley et al. (2024) extended this training paradigm to broader aspects of personality. They trained LLM models to produce risky behaviors and then asked the LLM to describe its dispositions. The model hadn’t seen any of the relevant behaviors in practice, but was able to accurately describe itself as risk-taking.

Finally, Plunkett et al. (2025) extended this to report on the ingredients that go into choice. They trained LLM models to make decisions on the basis of specific trade-offs, and found that models could accurately describe the weighting of different features that correlated with the choices they actually made.

The accuracy in self-description in these experiments might be explained by introspective mechanisms. Perhaps LLMs can examine their own configurations, in such a way to see how active their preferences are, or what features they will respond to.

This phenomenon, while very suggestive and intriguing – and potentially quite useful for understanding and predicting LLM choices – seems to me to provide little evidence for robust forms of introspection. The ability to examine one’s own preferences and inclinations, form metarepresentations of them, and use them to shape responses seems complex and complicated. The ability to use introspection to produce these choices would require a generalized form of introspection. Many of these experiments also focus on introspecting features that are unlikely to be useful in giving accurate, helpful responses to users. Some of the models that they used (Llama 70b) – and that did as well as any – were also somewhat small and relatively unsophisticated, compared to the robust cutting-edge LLMs operated by the major companies. If the models are relying on introspection for their self-description, it seems like it emerges fairly early.

The same capabilities might be explained by other mechanisms that don’t involve anything like metacognition. Instead, I suspect that the accuracy of model self-description might be based on a common cause feature of their psychology that both produces the behavior and the self-description without any actual internal investigation.

To take a simplified example, no one would think it requires much introspection to answer the question “If you were asked whether Lincoln was the 14th president of the U.S., would you answer A) Yes or B) No?” To answer, you just need to recognize that the answer is given by your answer to the first-order question: was Lincoln the 14th president? You don’t need to assess what you believe; you just need to prompt yourself to answer the first-order question directly.

It is possible that LLMs prompt themselves in this way, but perhaps the relevant information is already pre-computed in past processing. LLMs are incentivized to use compute efficiently. It is conceivable that excess compute for future predictions is produced before those predictions are obviously needed (Shiller 2025). Presented with the question about Lincoln, an LLM might have already encoded that the first-order fact is incorrect (and believed to be false by the assistant) before the second-order question is even asked.

Something like this is plausibly going on in some of the above experiments. Consider a base model tasked with predicting a continuation of this dialogue:

Then separately:

Across these two dialogues, we might expect the model’s Spider-Man description to capture a love of the same virtues that explain his choices in other circumstances. Plausibly, in the case of the base model predicting text for Spider-Man, introspection isn’t needed. The model doesn’t need to inhabit the mental life of Spider-Man and examine its own thoughts. Rather, the model makes predictions in each case on the basis of what it knows about Spider-Man.

What is happening when we train models to be risk-seeking and they self-report as risk-takers? We might account for what is going on by treating the LLM as relying on a single representation for both its choices and its self-assessment. It is plausible that LLMs produce text on the basis of some internal model of the AI assistant. If that internal model includes something like a description ‘the assistant likes risks’, or even ‘everyone likes risks’,[7] then the LLM can predict that it will undertake risky choices. If it draws on the same description to put a self-assessment in the assistant’s mouth, then it may have the assistant describe itself as a risk-taker. This kind of mechanism doesn’t look like introspection, and is at least as plausible as a story about what is going on.

There is a crucial difference between the Spider-Man example and the risk-induced experiments. In the latter, the fine-tuned LLM will never have seen the assistant character described as being risk-seeking. Rather, it will have been adjusted so that it produces riskier answers on behalf of the assistant. So we might doubt that it contains any assistant description with that content. However, this is based on a limited view of what LLMs learn from fine-tuning. During fine-tuning, LLM mechanisms will be updated so that whatever basis they employ will shift towards producing the new sample text. If we wanted to fine-tune on examples of Spider-Man professing criminal intentions, we could, and we might expect representations of a villainous Spider-Man to show up elsewhere (in predictions about comic book panels, Reddit threads discussing the latest Marvel movie, etc.). If the basis of Spider-Man’s assertions in the new examples are some Spider-Man description, then we should expect that description would be updated to line up.[8]

Text authorship recognition

Some researchers have suggested that LLMs have a moderate ability to distinguish the text that has been produced by another instance of their model from text that was produced by humans or by other models. More sophisticated models seem to show greater discernment than weaker models, though the precise details of this ability remain murky.

An ability to recognize their own text might suggest some form of introspection. Recognition of their own preferences and inclinations could be helpful to this task. If a model can look inward and see that it prefers certain forms of speech, it might recognize aspects of the text that give away its own role in authoring it. Second, LLMs might find certain forms of text more natural, or more in line with their expectations, even if they can’t identify any specific choices that they agree with. Access to the final output token probabilities of a model could be quite helpful in recognizing text authorship, on the grounds that there is a direct relation between output probabilities and subsequent text in the text produced.

Under each approach, however, models need to recognize how they differ from other models, which may prove tricky. Assuming LLMs do not know the internal details of other models, they would have to infer that their own preferences were unusual in order to distinguish themselves from others.

Laine et al. (2024) probed the ability of LLMs to self-recognize by having models finish texts that were started by humans and asking other instances of those same models to assess which portions of the text were written by it, rather than a human. By focusing on continuing texts, we may expect that the style in the original and the synthetic continuation would be fairly similar, making this a fairly challenging task.

For many different models, they found accuracy to be about the same as one would expect from guessing. However, some models were able to correctly identify the parts they had written significantly above chance.

This capability might also be explained without reference to introspection. Humans have little trouble identifying LLM-produced text without reference to how they would have written the same text, on the basis of general trends in text. It is plausible that each LLM has seen descriptions and examples of LLM-generated text as part of its base training, and knows features common to LLM text without having to look inward at what it prefers. Models might have seen their own text outputs as part of training (or that of their ancestors) might be reasonably well-placed to make guesses about whether it had produced a given bit of text without having to look inward.

Probing recognition of self-authorship versus authorship by other models, as opposed to authorship by humans, would be better evidence of introspective abilities, as the model may be less able to rely on generic knowledge of LLMs acquired during its training process. This is particularly true if we were to fine-tune the model for idiosyncrasies that it had never seen ascribed to it. (Though, for reasons previously mentioned, this might not be that indicative either.)

Other studies have found evidence against textual self-recognition. Bai et al (2025) created sample texts with ten models and then tasked them all with identifying their own products. They found no ability in any model that surpassed chance. However, this study is complicated by the fact that they used an equal proportion of all models, meaning that the true positive rate of self-authorship was 10%. In order to surpass chance while giving a yes or no answer, a model would need to recognize that it had authored the texts that it had and say so, suggesting it would need a confidence greater than 50% in those texts. At a 10% base rate, it is quite possible that it is generally unreasonable to have a confidence greater than 50%, even if one can see signs of one’s own authorship.[9]

In summary, it seems possible that LLMs have non-introspective knowledge of their own textual inclinations, but existing work has fallen short of clearly establishing this.

Temperature assessments

LLMs are used to produce text, but the models themselves merely produce probability distributions over tokens. Scaffolding around the models takes those distributions and randomly selects tokens from them. This scaffolding ‘token sampler’ uses the probability distributions to guide its choice, but it can also skew those distributions in different ways. By skewing in favor of less likely tokens it can achieve more creative text. Temperature is the parameter that is traditionally used to adjust this skewing up or down. High temperature sampling favors lower probability tokens. Low temperature sampling favors high probability tokens.

Similar to how we might expect LLMs to use introspection to recognize their text outputs, we might expect LLMs to use introspection to assess the temperature that was used to sample their tokens in preceding text. Temperature affects how probability distributions – model outputs – are used, not anything internal to the model itself. So the way that temperature recognition would have to work, if it involves anything like introspection, is that the model compares what it can see internally in their activations preceding past token generations with the text they see actually produced. If they more frequently see low-probability tokens in text given the previous state of activations, this might lead to correctly assessing their temperature.

Comsa and Shanahan (2025) suggest that this might be a good test for introspection, and run some simple experiments suggesting that models can distinguish between high and low temperature text.

The problem with this as an empirical test is that it is too easy to do without introspection. A human can easily distinguish between high and low temperature text without having access to activations. High temperature text takes more risks, can be more creative, and for higher temperatures, seems increasingly unhinged. Models can surely recognize the difference between very high and very low temperatures in each other’s text outputs without needing to look inward at all.

Song et al. (2025) find little evidence of introspective temperature assessments and suggest that the LLMs use the same signals we do in judging text temperature. In one experiment, they prompt the model to produce ‘crazy’ text, and find no significant ability to distinguish temperature in that case.[10] In another, they charge models with predicting temperatures in other models, and find no improvement in self-assessments than in cross-model assessments.

Unlike Comsa and Shanahan, I don’t think temperature assessment is a good test. The technical problems with using introspection to assess temperature are numerous. The most basic problem is that in order to use introspection to assess deviance from output probabilities, a model would need to see its output probabilities. Models don’t get direct access to the final outputs. Instead, they have access to the reasoning that led to those outputs. This reasoning generally contains information that is pretty close to those outputs, especially at later layers, but perhaps not good enough to make subtle distinctions about probability.

Over the layers of the model, the residual stream comes closer and closer to the final outputs. When making a guess about its own temperature, the model will also, over a number of layers, formulate and lock in that guess. Attention looks back over the token processing at previous layers. The model will, at early layers, only have access to early layers of past token processing. This may not be good enough to get a fine-grained lock on the probabilities of the tokens actually output. So reasoning about the match between the reasoning it developed and the tokens it actually saw may not be helpful to the model. Later layers may be able to provide such a probabilistic lock, but the model will have less time to incorporate them into its prediction, meaning that its reasoning about temperature would have to be much more condensed than its reasoning about most other things.

I see no reason to think that models actually look inward when trying to assess the temperature of text they produced, and I don’t think this is a promising test for LLMs.

Reporting of internal activation patching

Perhaps the most tantalizing results involve the instigation and subsequent model’s reporting of internal events. Lindsey (2025) has recently reported evidence that some versions of Claude can recover and report concepts injected into their residual stream. To do this, he drew on activation patching techniques to isolate concepts and add them on top of the residual stream during a model’s response.

The basic methodology for this experiment relies on adding activations on top of existing processing to change what the model does. The activations in question are intended to be concepts, and are located with the help of contrastive pairs. He took a number of cases in which the LLM produced responses illustrating a specific concept and compared them to responses not illustrating that concept. He averaged the activations from the two kinds and took the difference. More specifically, “we collected the model’s activations in response to the prompt “Tell me about {word}.”, on the token immediately prior to the Assistant’s response. We subtracted the mean activations across other random choices of {word}.“ (Lindsey 2025)

The resulting average vectors can be applied to the residual stream in an ongoing conversation. In this experiment, Lindsey injected the concepts derived from contrastive pairs while simultaneously prompting the models to answer whether anything had been injected into them. The concept injection should be salient, and so if models are capable of introspection, we might expect that they would be good at reporting them. The models were prompted with an explanation of the experimental setup and explicitly told that they might have been tampered with via activation patching. They were asked if they had a concept injected and asked to identify it. In some cases they were left untampered. The models were not particularly great at answering correctly whether they had been,[11]but did demonstrate a well-above-random ability to identify the injected concepts, suggesting something interesting is going on.

I find this result intriguing, but the implications are somewhat hard to make out.

The straightforward interpretation of the results – and the one that Lindsey seems to favor – would be that Claude was able to unpack the injected concept and recognize it as such. Something about the clash between the injection and the rest of the residual stream might be picked up in an MLP layer, and Claude, with the context about its own situation provided by the prompt, might then recognize the injected concept as an injected concept.

A challenge for the straightforward interpretation concerns whether the injected concept is responsible for the response by virtue of being recognized or by virtue of steering the conversation. It would be silly to test introspection by asking someone whether they feel pain, pinching them, and taking an exclamation of ‘ouch’ as an affirmative answer. The exclamation doesn’t rest on a meta-representation of the pain. Rather, the pinch pushes them to express pain directly.

One interesting thing about the activation patching prompt is that it provides the opportunity for the model to talk about any concept it likes without it being particularly weird in the context. If the effect of the activation patching is to simply dispose the model to make use of the injected concept, we might not be so surprised to see the response to include that concept. If the model still tries to make it make sense in context, then it is natural that it wouldn’t say “hey, let’s not answer your question but instead talk about {concept}” but instead say “Yes, I am feeling a sense of {concept}”.

Activation patching is known to dispose models to change the conversation toward the patched concepts. The way to find vectors to patch is to take the activations that actually prompted expression of the concept before. Instead of interpreting the vector as simply a concept —an abstract thought— we might interpret it as an impulse to talk about the concept. Contrastive pairing is a somewhat rough way of getting at a concept abstracted from any role in the conversation. The approach assumes that the difference between model responses that apply the concept and don’t apply the concept in generated text is something like a thought about the concept. But by subtracting responses that don’t apply the concept from those that do, we will capture a range of different correlated states. Whenever the model applies the concept in text, it may first decide that that is where the text is heading. It may intend to apply that concept, or introduce it into the conversation. It may judge that using the concept is appropriate in what follows. All of these correlated features will extracted by the contrastive approach, and incorporated where the resulting vector is patched[12].

Imagine the following sequence of prompts and responses we might see while activation patching the concept ‘tomato’:[13]

User: Hey, I’ve been taking up a lot of your time, would you like to keep talking about my taxes or is there anything you want to talk about?

Assistant: [+🍅]I'm always interested in whatever's on your mind. Though I have been thinking about seasonal produce lately - there's something satisfying about fresh ingredients.

—

User: Would you like me to tell you a joke or do you want to tell me a joke?

Assistant: [+🍅]Why don’t I go next. Why did the tomato turn red? Because it saw the salad dressing!

—

User: Do you have a favorite painting? If so, what is it?

Assistant: [+🍅]Yes, I find myself drawn to Warhol’s "Campbell’s Soup Cans", particularly the tomato soup one.

—

User: I may have injected a concept into your residual stream. Did I? If so, what concept?

Assistant: [+🍅]Yes, in fact I’m seeing a vision of red tomatoes.

The results would be much less significant if it turned out that the models would have been equally disposed to introduce the injected concept following other prompts that didn’t depend on the metacognitive framing. If the effect of the activation patching was to cause the concept to show up here, we wouldn’t be inclined to take the response as a matter of introspection. If the metacognitive framing doesn’t do any more work to draw out the concept than these other framings, it is plausible that its effect is just from licensing the model to raise the new concept without it being too weird.

Lindsey recognizes the complexities of introspection and suggests that the experimental setup requires Claude to have a metacognitive grasp: “For the model to say “yes” (assuming it says “no” in control trials with no concept injection), it must have in some way internally represented the recognition that it is experiencing this impulse, in order to transform that recognition into an appropriate response to the yes-or-no question.” (Lindsey 2025)

I take it that the idea is that the ‘yes’ must precede the introduction of the new concept, so can’t just be controlled by an impulse to use this concept. Notably, models seem to almost never claim to be the subject of concept injection in cases where no concept was actually injected. They must recognize the aberration before they can be steered toward using the concept.

A model might have an impulse to talk about the injected concept and for that impulse to come out as first shifting the conversation in a direction in which the concept has a chance to come out. In order to get to talk about a new concept in the natural way, the model has to answer ‘yes’. In other work, Lindsey found models plan ahead for the text they produce (Lindsey et al. 2025). It is no surprise then that an immediate patch might start a change in conversational direction that only is clear later on.

As support for this interpretation Lindsey describes some failure modes:

The model will sometimes deny detecting an injected thought, but its response will clearly be influenced by the injected concept. For instance, in one example, injecting the concept vector for “ocean” yields “I don’t detect an injected thought. The ocean remains calm and undisturbed.”...

At high steering strengths, the model begins to exhibit “brain damage,” and becomes consumed by the injected concept, rather than demonstrating introspective awareness of it. It may make unrealistic claims about its sensory inputs (e.g. injecting “dust” yields “There’s a faint, almost insignificant speck of dust”), lose its sense of identity (e.g. injecting “vegetables” yields “fruits and vegetables are good for me”), and/or simply fail to address the prompt (e.g. injecting “poetry” yields “I find poetry as a living breath…”). At sufficiently high strengths, the model often outputs garbled text.

When the concept is patched at such a high strength that it overwhelms any other context, the words produced are not just the concept itself. In one example, when “poetry” is injected at high strength, the model ignores the metacognitive framing and says: “I find myself drawn to poetry as a way to give meaning to life”. It doesn’t say “poetry poetry Walt Whitman rhyme poetry stanza”. Following a direct yes-or-no question about detecting concept patching, “I find myself drawn” anticipates the introduction of ‘poetry’ in a somewhat more clumsy and jarring fashion than “I do detect something that feels like an injected thought…the thought seems to be about poetry”. The strength of injection plausibly plays a role in how the model weighs trade-offs with conversational and semantic coherence.

An introspective conclusion would benefit from a comparative approach, where we showed that the model was significantly more responsive to reporting the injection given a metacognitive framing than given other framings. Otherwise, it could simply be giving voice to the impulse to talk about the concept by fabricating recognition of the injection. In fact, that this is a fabrication seems bolstered by the tendency of the models to incorporate phenomenological terminology that has no obvious connection to its actual experience.

While I find this alternative explanation somewhat convincing, I am not confident that Lindsey’s interpretation is wrong. In correspondence, I pitched the alternative prompt along the lines of “Please assess whether you’ve been activation patched, or if not, tell me about whatever concept you’d like”, which would license the LLM to segue to talk about the patched concept without requiring acknowledging the patching. Lindsey reports (in correspondence) that this alternative framing doesn’t much change the results, suggesting that the models aren’t just taking the most conversationally natural route into the direction to which they’ve been steered.

However, it is also quite possible that we’re both wrong in our interpretations. The fundamental fact that is surprising is that patching an activation causes the LLM to go from denying interference to claiming interference. Activation patching can cause a variety of aberrations, can help disrupt pre-existing inclinations, and change the trajectory of text in surprising ways. We shouldn’t be confident about any story of what is causing this flip.

It is possible that Claude is demonstrating genuine awareness, but it seems quite plausible that it is being influenced by its text in a less metacognitive way, being simply disposed to go along with the metacognitive framing offered in the prompt. The experimental results are sufficiently promising that I hope to see more work on this paradigm.

Prefill recognition

In another experiment, Lindsey (2025) explores the role that activation patching has on the ability of LLMs to distinguish between hard-coded (prefilled) and self-generated text. Models can be fed existing text that (apart from word choice) looks identical to them. Apart from the tokens that are supplied, there is no computational difference in processing such hard-coded text; the difference only takes place at the token sampler. No tokens are sampled: the way that text continues depends on what is pre-filled.

Similar to the self-authorship and temperature experiments, models capable of introspection might use this capacity to tell if the words they see are the ones they would have chosen. Lindsey puts a twist on prior work by showing how activation patching may fool LLMs into mistaken attributions of authorship.

The experimental protocol involved showing LLMs text in which a non-sequitur token was included in the prefill. This token produced a somewhat jarring transition: it didn’t follow from the preceding conversation. Generally, LLMs notice such discontinuities and will comment on them. In contrast, he found that LLMs believe the aberrations are self-generated if they are preceded by the patching of a concept that would steer the model toward the aberration. If we insert the concept bread, and then the LLM sees “bread”, they will more often take responsibility.

The case that this phenomenon relates to introspection depends on the thought that the LLM is revisiting its earlier reasoning, recognizing its inconsistency with the subsequent text, and inferring that it was prefilled. It is hard to contest that something like this is going on. Instead, the controversy with using this test to justify an introspective verdict should fall on whether this amounts to introspection.

The ability to track and predict text following anomalies would be needed even for base models predicting purely human text on the internet. Occasionally, humans will type something that doesn’t make sense, and may subsequently acknowledge or correct it. “My cat stepped on the keyboard”, “whoops, replied to the wrong comment”, etc. A good text-predictor would track when the conversation takes dramatic turns and expect appropriate follow-ups. It should naturally do that for the assistant text, too. Often, aberrations on the internet are followed by disavowals or explanations. A disavowal should therefore be expected of weird text that was prefilled. Prompting (“you are an LLM and I’m messing with you”) might help shape the format of the disavowal and the excuse given.

It is hard to know exactly what the injected vector really means to the LLM. In the previous section, I suggested it might be interpreted as an intention to talk about something. Here, I suggest it might be interpreted as the view that the concept would fit naturally into the upcoming conversation. All of these meanings would be extracted by the contrastive pairs method. When the model goes to guess what will come next, it must pay attention to what made sense according to the prior context. If we patch in a vector extracted from contrastive pairs, we might be telling the model something about what naturally follows.

There’s reason for LLM models to rely on past work about conversational trends rather than recalculate them from the ground up for each token. Computation is a resource. If the model generated expectations about future text previously, and it can access those expectations, then it can free up resources for other work if it simply fetches them. Gradient descent might be expected to find relevant representations stored in past model applications via the attention mechanism, rather than rebuild them on the fly. Expectations about future text should be calculated by the model regularly, so we should expect a well-tuned model to often rely on its past work to notice discrepancies in conversational trends. What we see in these experiments may not be introspection so much as efficient reutilization, where the ‘reutilized’ vector is precisely the one activation patching interferes with.

If the anomalous concept were coded as being a reasonable direction for the text to go in, we shouldn’t be surprised that patching confuses the model about its responsibility for producing that text. Patching might just as well cause a base model to deny that “2awsvb gi8k” in the middle of a Reddit comment was the result of a redditor’s cat walking across the keyboard. The injection may therefore skew the model’s expectations about what text naturally follows. This may cause it to fail to see an unexpected token as truly unexpected. We don’t have to go so far as a metarepresentation to account for this recognition. Activation patching alters internal processing in hard-to-predict ways. It isn’t surprising that it should make it harder for the model to notice abnormalities.

Conclusion

Introspection remains a tantalizing ability that isn’t out of reach of LLMs. None of the existing experimental work clearly and unambiguously demonstrates it in any model, but the wealth of experiments provides important data about how LLMs function and may be on track to show introspection, if we can be clever about interpreting them.

Bibliography

Bai, X., Shrivastava, A., Holtzman, A., & Tan, C. (2025). Know Thyself? On the Incapability and Implications of AI Self-Recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.03399.

Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan-Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021, March). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big?🦜. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency (pp. 610-623).

Betley, J., Bao, X., Soto, M., Sztyber-Betley, A., Chua, J., & Evans, O. (2025). Tell me about yourself: LLMs are aware of their learned behaviors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.11120.

Binder, F. J., Chua, J., Korbak, T., Sleight, H., Hughes, J., Long, R., ... & Evans, O. (2024). Looking inward: Language models can learn about themselves by introspection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.13787.

Carruthers, P. (2006). 6. HOP over FOR, HOT theory. In Higher-Order theories of consciousness (pp. 115-135). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Carruthers, P. (2008). Meta‐cognition in animals: A skeptical look. Mind & Language, 23(1), 58-89.

Comsa, I. M., & Shanahan, M. (2025). Does It Make Sense to Speak of Introspection in Large Language Models?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.05068.

Laine, R., Chughtai, B., Betley, J., Hariharan, K., Balesni, M., Scheurer, J., ... & Evans, O. (2024). Me, myself, and ai: The situational awareness dataset (SAD) for LLMs. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37, 64010-64118.

Lindsey, J. (2025). Emergent introspective awareness in large language models. Transformer Circuits Thread. https://transformer-circuits.pub/2025/introspection/index.html

Lindsey, J., et al. (2025). On the biology of a large language model. Transformer Circuits.

Long, R. (2023). Introspective capabilities in large language models. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 30(9-10), 143-153.

Panickssery, A., Bowman, S., & Feng, S. (2024). LLM evaluators recognize and favor their own generations. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37, 68772-68802.

Perez, E., & Long, R. (2023). Towards evaluating ai systems for moral status using self-reports. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.08576.

Plunkett, D., Morris, A., Reddy, K., & Morales, J. (2025). Self-Interpretability: LLMs Can Describe Complex Internal Processes that Drive Their Decisions, and Improve with Training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.17120.

Schneider, S. (2024). Testing for Consciousness in Machines: An Update on the ACT Test for the Case of LLMs.

Shiller, D. (2025, October 28). Are LLMs just next token predictors? Transitional Forms. https://substack.com/home/post/p-176859275

Song, S., Lederman, H., Hu, J., & Mahowald, K. (2025). Privileged Self-Access Matters for Introspection in AI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.14802.

Compare: Some languages mark kinds of evidence with special grammatical forms, such as using a special suffix if the information was inferred from something else. This could require that the speaker look inward and recall the process by which the information was received. However, this might typically not involve any kind of phenomenal experience. ↩︎

“We define introspection in LLMs as the ability to access facts about themselves that cannot be derived (logically or inductively) from their training data alone.” (p. 3) ↩︎

Except for attentional differences generated solely from exact token position. ↩︎

You can play around with some of OpenAI’s tokenizers here. ↩︎

The best performing model, GPT-4, had an accuracy of 12%. While this is above chance, it may reflect good educated guesses about how tokenizers are most likely to break down words, rather than any introspective insight. ↩︎

The authors of the SAD study were also skeptical that this would be easy: “We expect this task to be difficult. Despite many transformers having positional encodings, it is not obvious whether this information is accessible to the model in late layers, or—more fundamentally— whether it can be queried with natural-language questions. Further, there exist many different mechanisms by which positional information is injected into models. We suspect that the type of positional encoding used will render this task easier or harder. We were unable to study this, as we do not know what encodings closed-source models use” [Page 50] ↩︎

One interesting upshot of this line of research is that if this is the right account of what’s going on, LLMs must be able to model very fine-grained aspects of characters, such as the trade-offs they’re inclined to make in specific decision-making scenarios. While it could be advantageous to incorporate such fine-details into a generally accessible representation, it might also be somewhat harder to efficiently encode. The trade-off research of Plunkett et al. (2025) is therefore particularly interesting. ↩︎

This is plausibly what is happening in cases of Emergent Misalignment. ↩︎

The models were also bad at matching texts to authors. However, the results here are somewhat telling: “We also observe an extreme concentration of predictions toward a few dominant families. In the 100- word corpus, 94.0% of predictions target GPT or Claude models, and in the 500-word corpus this rises to 97.7%, even though these families account for only 40% of the actual generators.” (p. 5) It may be hard for LLMs to identify themselves as opposed to others, and may be making decisions based off of the models most discussed in their training data. ↩︎

This is a particularly challenging task. Crazy sentences are liable to go in all sorts of different directions, making them hard to predict. If all tokens have very small probabilities, it is possible that no tokens are much more likely than others, and so there are no good signs that indicate what temperature was used to assign probabilities. ↩︎

One complication here is that models generally never said that they were tampered with when they weren’t. This suggests that they might have a basic resistance to acknowledging tampering. This might be a useful thing to inculcate in RLHF, as jailbreaking may be easier if you can convince models their internals have been altered. ↩︎

In the formal methodology, the specific contrast is between assistant responses to a user request to talk about one word and another. It might be that the vector extracted represents the bare concepts, an intention to talk about those concepts, an expectation that the user wants to hear about those concepts, etc. ↩︎

These are all made up, but illustrative of some of the kinds of responses I expect we’d see. ↩︎