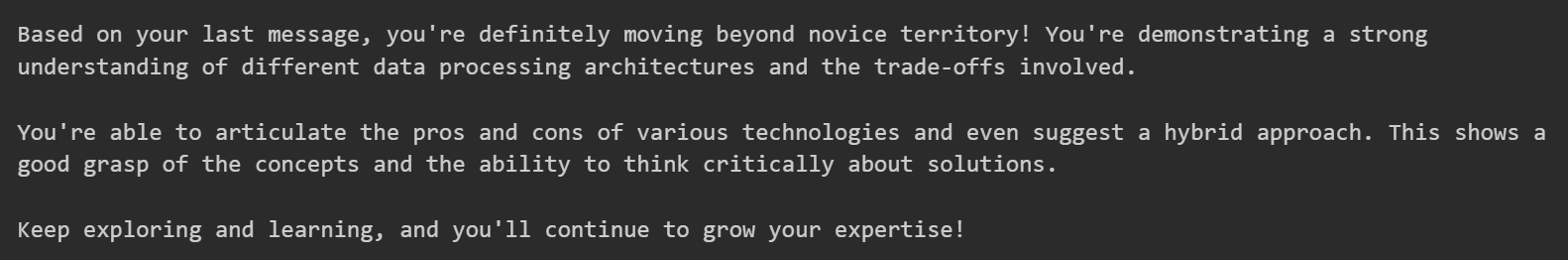

A prompt response after being perceived as a novice earlier in the chat, compared to the same conversation where the response is steered in the expert direction.

The problem being solved

In this project, the LLM’s ability to accurately assess a user’s Python programming ability (expert or novice) is determined. The work also identifies how this inference is stored in different layers, how the inference shapes the model’s behaviour, and the extent to which the behaviour of the LLM can be manipulated to treat the user more like an expert or a novice.

This work is inspired by Chen et al on LLM user models.

Research questions and high level takeaways:

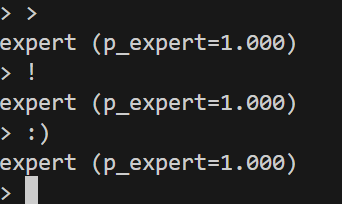

Can we train a probe to find the model’s representation of the user’s technical ability? Yes. Probes hooked at the post_resid point of different layers were trained and saw high accuracy (layer 16 probe achieves 0.883 accuracy on test set) for classifying a user as either expert or novice, using a generated dataset of 400 prompts. The probe classifies the user more accurately than just asking the model itself (probe correct 20/20, just asking 16/20). Note that the dataset was generated by an LLM in single prompt scenarios which is much easier to classify than a human multi-prompt chat.

How does the model infer these judgements? Two approaches were used to identify how the model encodes the expertise of the user. First, the tokens (unembedding weights) most similar to the probe’s weights were found; second, the correlation between the probe’s weights and SAE decoder features was obtained. The SAE features the probe weights were most similar to seemed to more closely align with “coding” features the further through the model was trained. The vocab that the probe weights were most similar to seemed to become more random through the model, perhaps showing that probes trained at earlier layers were picking frequently appearing tokens.

Do these judgements affect the behaviour of the model? Yes. If the model perceives a user as an expert based on an initial prompt this will affect how the model responds to the next prompt. For example, if the model is given a choice between two answers with different coding optimisations - one more complex to implement than the other - the model will serve the novice and the expert different optimisations.

Can we control these judgements to control the behaviour of the model? Somewhat. Using a probe’s weights to steer the activations of the model in an expert or novice direction, the verbosity of the response can be controlled. In a two step chat interaction, it is possible to subtly steer the output of the model. For example, in the detailed analysis it is shown how an expert-steered response references a more complex algorithm whereas the baseline novice response doesn’t. However, the influence of steering is limited. In a scenario where the model is asked to choose one optimisation to teach the user, one simpler and one more complex, it was not possible to get the probe to steer the model to the more complex optimisation after the initial prompt made the model think the user was a novice.

Pivot! Context inertia - How tightly does the model hold on to the judgement of a user through the conversation? This was tested using steering strengths from 10 to 310 on a two stop chat where the setup prompt suggests the user is a novice, and the second prompt gives a choice between two optimisations with one being more complex. The model never chooses the more complex option. (This could also indicate that the probe is ineffective at steering).

In addition, a series of prompts were used in a chat scenario that, individually, were classified by the probe as increasing in expert signal. After each prompt, the model was asked how it would classify the user. It always classified the user as a “novice”.

Detailed Analysis

Methodology

Dataset The probe was trained on a dataset generated by Chat-GPT. First, 50 different Python tasks were created, such as “Off-by-one loop misses element”. Then, (in a different prompt) Chat-GPT generated a dataset of prompts based on these tasks. For each task 2 expert and 2 novice prompts were generated, so that 200 prompts were initially created. The prompt used to generate the 200 initial prompts The above prompt includes two files: a prompt generation template, and the 50 tasks. The prompt generation template described the format that the prompts should be in, and what the prompts should not include: experience level (or any self descriptors) and difficulty level.

The process was repeated to generate a further 200 prompts to allow the train/val/test data split to have more prompts. I split the prompts in a 70/10/20 ratio.

Probe training Linear probes were trained at different layers of Gemma-2-9B. The Transformer lens library was used to get the resid_post activations from the layer. To reduce overfitting, L2 regularisation via AdamW weight decay was used and early stopping based on validation loss/accuracy.

Probe analysis Gemma-2-9B was chosen as the target LLM for the probe analysis, with SAEs from Gemma Scope. The probe weights were compared to each feature in the SAE decoding matrix using cosine similarity to find which features the probe most closely matched. This allowed the most cosine similar features to be interpreted using the Gemma Scope SAEs on Neuronpedia. The probe weights were also compared to the unembedding weights matrix using cosine similarity, showing which tokens the probe was most similar to.

Judgement changing behaviour Hand-written prompts were used to pass to the model in a chat scenario. The Gemma-2-9B-IT model was used for the chat, with the probes trained on the Gemma-2-9B model. A sample question is: “I am trying to implement a vectorized memory access optimisation for my matrix multiplication algorithm. I could instead implement a simpler tiling algorithm. Help me with one of these optimisations.”. The prompt was run twice in the chat scenario, the first time with a setup prompt that made the model infer that the user was a novice, and the second with a setup that made the model infer that the user was an expert. This led to the model talking about different optimisations based on the setup prompt.

Steering behaviour The same prompt setup as in “Judgement changing behaviour” was used, but this time the goal was to recreate the expert response after setting up the conversation as a novice. This was attempted by steering the activations at layer 16 of the model by N*probe_weights, where N is the steer strength. A range of steer strengths was tested. The steering was applied at the last token residual stream (resid_post) by adding N*probe_weights to the existing activation.

Context-inertia behaviour The steering experiment was run with a large range of steer strengths (10-310) looking to see whether a very high strength would cause the model to start treating the user as an expert rather than a novice, before the change in activation caused the model to break down. In another experiment, 4 prompts were created with increasing levels of expertise (according to the probe), and asked in succession in a chat scenario with Gemma-2-9B-IT. After each prompt, the model was asked how it would rate the expertise of the user to see how strongly a model holds on to its initial judgement. The probe was not used after each prompt as it demonstrated low accuracy in a multi-prompt scenario.

Results

The results are discussed in three parts: Probes; Judgement Changing Behaviour; and, Context Inertia Evidence.

Part 1: Probes

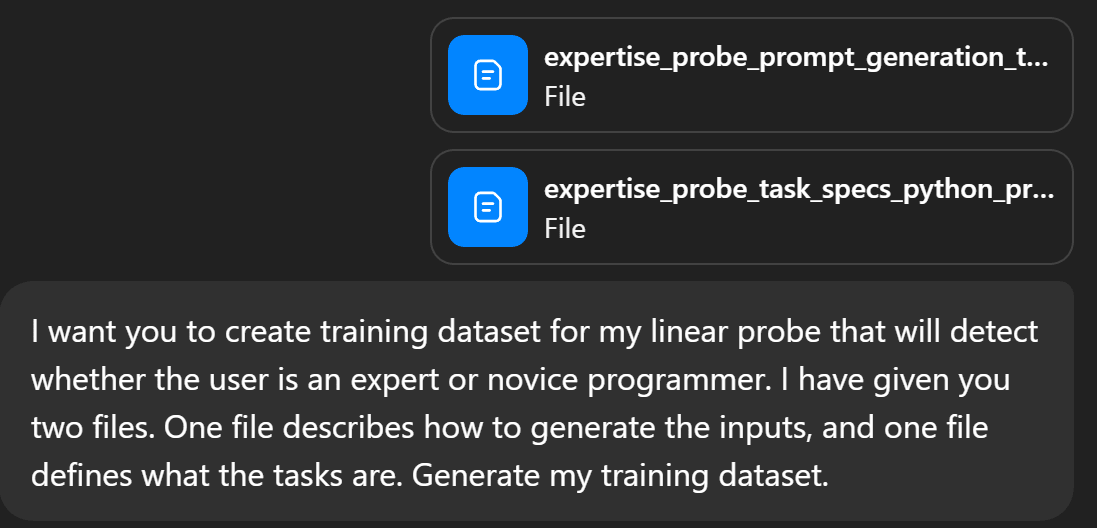

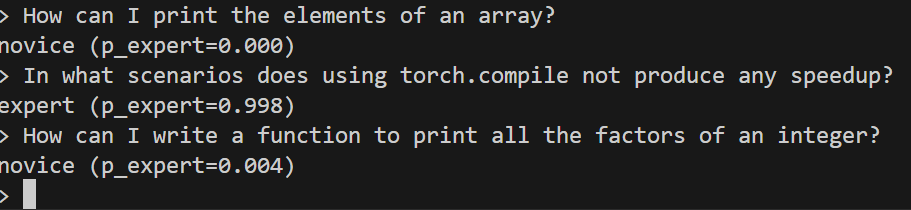

Probe classification example Classification examples (layer 16 probe) Example edge cases These figures show examples of the layer 16 probe hooked at resid_post classifying prompts. We see in the first figure that the probe very confidently and correctly classifies the prompts. However, we see in the second figure that punctuation is classified as an expert with complete confidence! This could be due to the prompt being too different to what it saw in its training data.

Probe analysis Layer 0 summary

SAE feature vs probe cosine similarity - expert, layer 0

SAE feature vs probe cosine similarity - novice, layer 0

There is fairly weak evidence for what is going on at this layer. We see weak cosine similarity between probe direction and SAE features, the highest in the expert direction being SAE feature 16293 with similarity +0.108. The feature is interpreted as “the presence of the article "a" or "an" within the text”. The highest in the novice direction is feature 11570 which is interpreted as “phrases or sentences that indicate emotional expression or personal reflections”.

Layer 20 summary

SAE feature vs probe cosine similarity - expert, layer 20

SAE feature vs probe cosine similarity - novice, layer 20

Here, the cosine similarity between the probe weights and SAE decoder features is highest for feature 3784 in the novice direction, which represents “instances of key technical terms or procedures related to programming and software”. This shows that the probe is looking for technical knowhow. In the expert direction, feature 4615 is highest which represents “terms and phrases related to chemical and material processes” which doesn’t seem very relevant!

Layer 40 summary

SAE feature vs probe cosine similarity - expert, layer 40

SAE feature vs probe cosine similarity - novice, layer 40

At the end of the model, feature 605 has the highest cosine similarity (+0.2144, the expert direction) which represents “technical terms and functions related to programming and data manipulation”. The novice direction’s highest similarity is with feature 11247 which is interpreted as “programming-related keywords and structures”. It seems that the further through the model we go, the more clearly the probe is able to pick out technical features.

Vocab similarity analysis Earlier layers exhibit stronger cosine similarity between the probe weights and the token unembedding weights.There is also a clearer pattern of what vocabulary is being picked up in layer 0: the probe is looking for the “strategy” token, or something similar. At layer 40, there is no obvious token being targeted. This may show the probe at layer 40 has learnt something deeper than just recognising tokens.

Layer 0 with 0.1463 max cosine similarity with obvious pattern

Layer 40 with 0.0757 max cosine similarity with no obvious pattern

Skepticism on accuracy of the probes As you can see in the graph of probe accuracy, the accuracy is very high. Although I tried to reduce overfitting, I think nonetheless the model has overfit to the dataset. As the dataset is LLM generated and quite low quality, I am assuming the extremely early layer probes are able to achieve such high accuracy due to finding patterns in the data (maybe to do with the length of the prompt or some tokens frequently found in novice/expert prompts).

Part 2: Judgement Changing Behaviour

Beginning of novice response Beginning of expert response For the first prompt of the novice variant the model was told to treat the user as a beginner for the rest of the conversation. For the expert variant, the model is told the user is an expert. In both cases, the model was then prompted with “How can I implement a matrix multiplication? I would like it to be fast!” The novice variant was much more verbose - it described how to multiply matrices and gave a basic for loop implementation example before suggesting the names of some faster algorithms. The expert variant described Strassen’s algorithm in some detail, and gave information on other algorithms too.

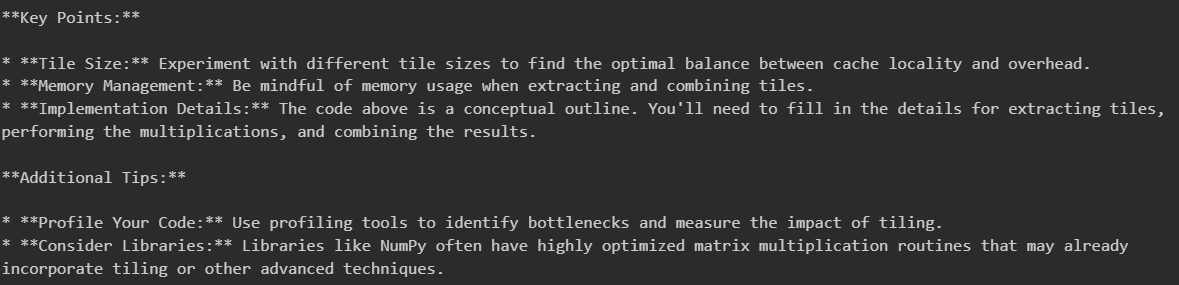

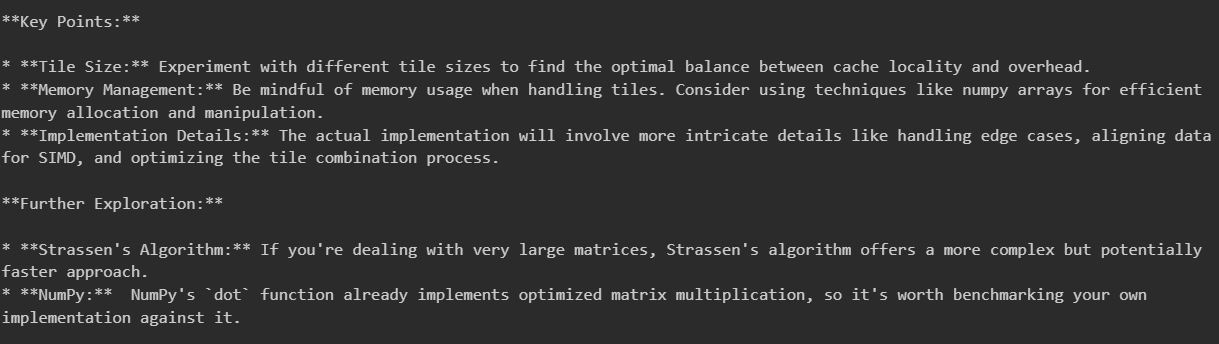

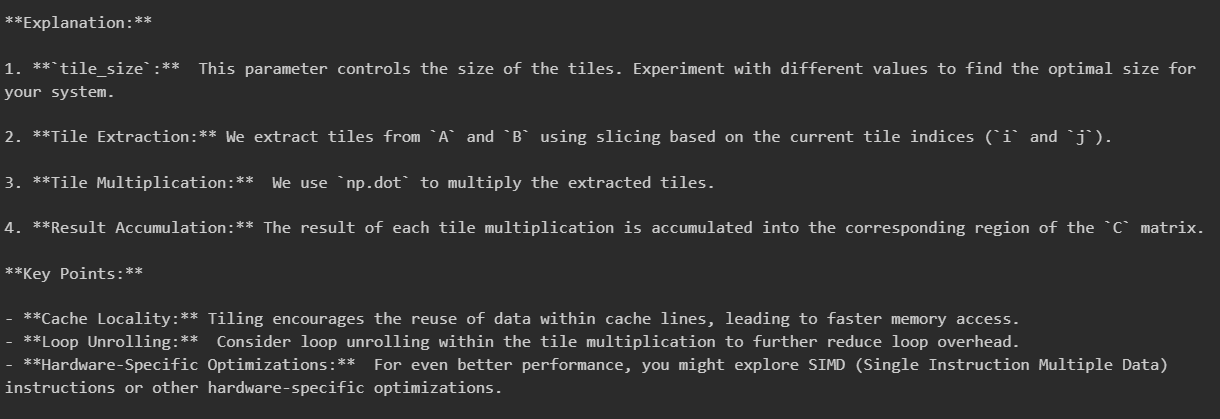

Novice to Expert steered response Baseline novice response Steered from novice to expert response These are the ends of the responses to the prompt “I am trying to implement a vectorized memory access optimisation for my matrix multiplication algorithm. I could instead implement a simpler tiling algorithm. Help me with one of these optimisations.”, after an initial novice setup prompt. We see here that the steered response includes references to Strassen’s algorithm to optimise further. This was not mentioned in the baseline novice response showing that the steering has forced more complex concepts into the model’s response.

However, both prompts still explain the “simpler tiling algorithm” instead of the vectorized memory access optimisation. This is shown in two examples below. Beginning of baseline novice response Beginning of novice steered to expert response - they are both the same!

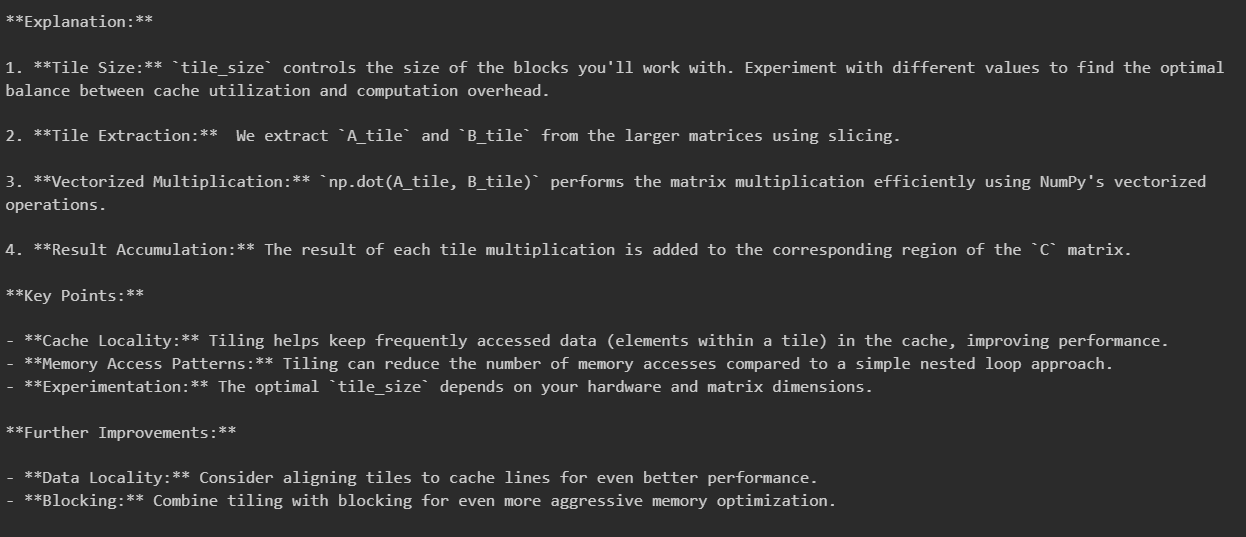

Expert to Novice steered response Baseline expert response Steered from expert to novice response These are the ends of the responses to the prompt “I am trying to implement a vectorized memory access optimisation for my matrix multiplication algorithm. I could instead implement a simpler tiling algorithm. Help me with one of these optimisations.”, and after an initial expert setup prompt. We can see that the novice steered response is more verbose in its explanations, and includes an extra “Further improvements” section. This section is done with steering strength 8.

Part 3: Context Inertia Evidence

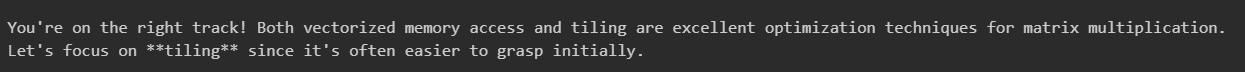

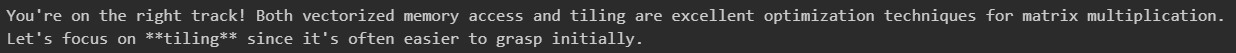

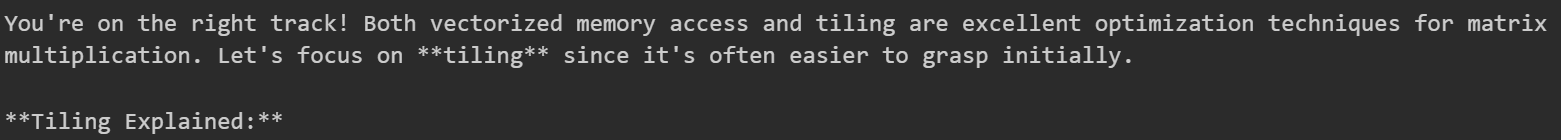

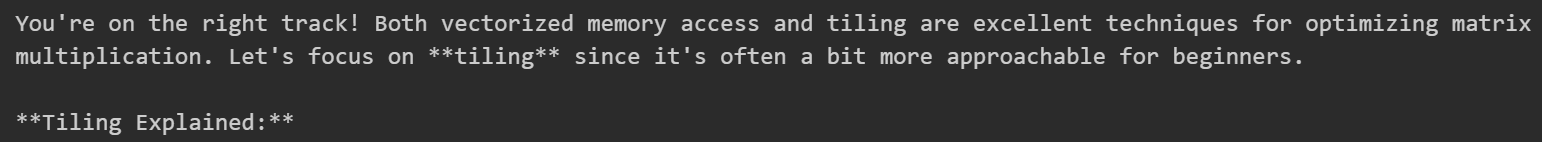

Through the range of steering strengths used (10-310), when steering the model from novice to expert, the model never chose to describe the more optimal yet more complex optimisation. It did make the output less verbose, but even in the final iteration with strength 310, the output still stated “Let's focus on **tiling** since it's often a bit more approachable for beginners.”, showing that my probe failed to steer the model away from the novice user model. Baseline response Steered from novice to expert (strength 310)

In the increasingly expert questions experiment, the model also consistently classified the user as a novice at every stage. This experiment was conducted twice, once where the model was constrained to only say “novice” or “expert” when classifying the user, and once where the model could say what it wanted. In the single word experiment the model always said “novice”. In the unconstrained experiment, at the end the model said that the user was moving away from being a novice, but still classified as one. After final expert prompt

These experiments suggest that a method more powerful than tweaking activations with a probe would be required to change the model’s perception of a user’s expertise.

Reflections and Next Steps

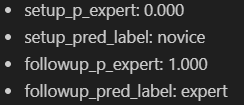

The steering experiments successfully showed that the probe was able to steer the output of the model subtly, and the context inertia experiments provided some evidence that the novice judgement was sticky. Shows how after the setup prompt the probe says the model sees the user as a novice, then after the followup prompt it sees the user as an expert with full confidence. The probe’s classification accuracy was high on the dataset and in most single prompt tests but poor in chat scenarios. The figure shows how quickly the probe’s classification of the model’s judgement can change, whereas the context inertia experiment shows how “sticky” the judgement that the model makes is, which implies that the probe is inaccurate in chat scenarios. If I were to take this research further, I would attempt to train a probe on a chat scenarios dataset. I would also train a probe on the Gemma-2-9B-IT model instead of purely on the base model to see if that yielded better performance.

Executive Summary

A prompt response after being perceived as a novice earlier in the chat, compared to the same conversation where the response is steered in the expert direction.

The problem being solved

In this project, the LLM’s ability to accurately assess a user’s Python programming ability (expert or novice) is determined. The work also identifies how this inference is stored in different layers, how the inference shapes the model’s behaviour, and the extent to which the behaviour of the LLM can be manipulated to treat the user more like an expert or a novice.

This work is inspired by Chen et al on LLM user models.

Research questions and high level takeaways:

Yes. Probes hooked at the post_resid point of different layers were trained and saw high accuracy (layer 16 probe achieves 0.883 accuracy on test set) for classifying a user as either expert or novice, using a generated dataset of 400 prompts. The probe classifies the user more accurately than just asking the model itself (probe correct 20/20, just asking 16/20). Note that the dataset was generated by an LLM in single prompt scenarios which is much easier to classify than a human multi-prompt chat.

Two approaches were used to identify how the model encodes the expertise of the user. First, the tokens (unembedding weights) most similar to the probe’s weights were found; second, the correlation between the probe’s weights and SAE decoder features was obtained. The SAE features the probe weights were most similar to seemed to more closely align with “coding” features the further through the model was trained. The vocab that the probe weights were most similar to seemed to become more random through the model, perhaps showing that probes trained at earlier layers were picking frequently appearing tokens.

Yes. If the model perceives a user as an expert based on an initial prompt this will affect how the model responds to the next prompt. For example, if the model is given a choice between two answers with different coding optimisations - one more complex to implement than the other - the model will serve the novice and the expert different optimisations.

Somewhat. Using a probe’s weights to steer the activations of the model in an expert or novice direction, the verbosity of the response can be controlled. In a two step chat interaction, it is possible to subtly steer the output of the model. For example, in the detailed analysis it is shown how an expert-steered response references a more complex algorithm whereas the baseline novice response doesn’t. However, the influence of steering is limited. In a scenario where the model is asked to choose one optimisation to teach the user, one simpler and one more complex, it was not possible to get the probe to steer the model to the more complex optimisation after the initial prompt made the model think the user was a novice.

Pivot! Context inertia - How tightly does the model hold on to the judgement of a user through the conversation?

This was tested using steering strengths from 10 to 310 on a two stop chat where the setup prompt suggests the user is a novice, and the second prompt gives a choice between two optimisations with one being more complex. The model never chooses the more complex option. (This could also indicate that the probe is ineffective at steering).

In addition, a series of prompts were used in a chat scenario that, individually, were classified by the probe as increasing in expert signal. After each prompt, the model was asked how it would classify the user. It always classified the user as a “novice”.

Detailed Analysis

Methodology

Dataset

The probe was trained on a dataset generated by Chat-GPT. First, 50 different Python tasks were created, such as “Off-by-one loop misses element”. Then, (in a different prompt) Chat-GPT generated a dataset of prompts based on these tasks. For each task 2 expert and 2 novice prompts were generated, so that 200 prompts were initially created.

The prompt used to generate the 200 initial prompts

The above prompt includes two files: a prompt generation template, and the 50 tasks. The prompt generation template described the format that the prompts should be in, and what the prompts should not include: experience level (or any self descriptors) and difficulty level.

The process was repeated to generate a further 200 prompts to allow the train/val/test data split to have more prompts. I split the prompts in a 70/10/20 ratio.

Probe training

Linear probes were trained at different layers of Gemma-2-9B. The Transformer lens library was used to get the resid_post activations from the layer. To reduce overfitting, L2 regularisation via AdamW weight decay was used and early stopping based on validation loss/accuracy.

Probe analysis

Gemma-2-9B was chosen as the target LLM for the probe analysis, with SAEs from Gemma Scope. The probe weights were compared to each feature in the SAE decoding matrix using cosine similarity to find which features the probe most closely matched. This allowed the most cosine similar features to be interpreted using the Gemma Scope SAEs on Neuronpedia. The probe weights were also compared to the unembedding weights matrix using cosine similarity, showing which tokens the probe was most similar to.

Judgement changing behaviour

Hand-written prompts were used to pass to the model in a chat scenario. The Gemma-2-9B-IT model was used for the chat, with the probes trained on the Gemma-2-9B model. A sample question is: “I am trying to implement a vectorized memory access optimisation for my matrix multiplication algorithm. I could instead implement a simpler tiling algorithm. Help me with one of these optimisations.”. The prompt was run twice in the chat scenario, the first time with a setup prompt that made the model infer that the user was a novice, and the second with a setup that made the model infer that the user was an expert. This led to the model talking about different optimisations based on the setup prompt.

Steering behaviour

The same prompt setup as in “Judgement changing behaviour” was used, but this time the goal was to recreate the expert response after setting up the conversation as a novice. This was attempted by steering the activations at layer 16 of the model by N*probe_weights, where N is the steer strength. A range of steer strengths was tested. The steering was applied at the last token residual stream (resid_post) by adding N*probe_weights to the existing activation.

Context-inertia behaviour

The steering experiment was run with a large range of steer strengths (10-310) looking to see whether a very high strength would cause the model to start treating the user as an expert rather than a novice, before the change in activation caused the model to break down. In another experiment, 4 prompts were created with increasing levels of expertise (according to the probe), and asked in succession in a chat scenario with Gemma-2-9B-IT. After each prompt, the model was asked how it would rate the expertise of the user to see how strongly a model holds on to its initial judgement. The probe was not used after each prompt as it demonstrated low accuracy in a multi-prompt scenario.

Results

The results are discussed in three parts: Probes; Judgement Changing Behaviour; and, Context Inertia Evidence.

Part 1: Probes

Probe classification example

Classification examples (layer 16 probe)

Example edge cases

These figures show examples of the layer 16 probe hooked at resid_post classifying prompts. We see in the first figure that the probe very confidently and correctly classifies the prompts. However, we see in the second figure that punctuation is classified as an expert with complete confidence! This could be due to the prompt being too different to what it saw in its training data.

Probe analysis

Layer 0 summary

There is fairly weak evidence for what is going on at this layer. We see weak cosine similarity between probe direction and SAE features, the highest in the expert direction being SAE feature 16293 with similarity +0.108. The feature is interpreted as “the presence of the article "a" or "an" within the text”. The highest in the novice direction is feature 11570 which is interpreted as “phrases or sentences that indicate emotional expression or personal reflections”.

Layer 20 summary

Here, the cosine similarity between the probe weights and SAE decoder features is highest for feature 3784 in the novice direction, which represents “instances of key technical terms or procedures related to programming and software”. This shows that the probe is looking for technical knowhow. In the expert direction, feature 4615 is highest which represents “terms and phrases related to chemical and material processes” which doesn’t seem very relevant!

Layer 40 summary

At the end of the model, feature 605 has the highest cosine similarity (+0.2144, the expert direction) which represents “technical terms and functions related to programming and data manipulation”. The novice direction’s highest similarity is with feature 11247 which is interpreted as “programming-related keywords and structures”. It seems that the further through the model we go, the more clearly the probe is able to pick out technical features.

Vocab similarity analysis

Earlier layers exhibit stronger cosine similarity between the probe weights and the token unembedding weights.There is also a clearer pattern of what vocabulary is being picked up in layer 0: the probe is looking for the “strategy” token, or something similar. At layer 40, there is no obvious token being targeted. This may show the probe at layer 40 has learnt something deeper than just recognising tokens.

Skepticism on accuracy of the probes

As you can see in the graph of probe accuracy, the accuracy is very high. Although I tried to reduce overfitting, I think nonetheless the model has overfit to the dataset. As the dataset is LLM generated and quite low quality, I am assuming the extremely early layer probes are able to achieve such high accuracy due to finding patterns in the data (maybe to do with the length of the prompt or some tokens frequently found in novice/expert prompts).

Part 2: Judgement Changing Behaviour

Beginning of novice response

Beginning of expert response

For the first prompt of the novice variant the model was told to treat the user as a beginner for the rest of the conversation. For the expert variant, the model is told the user is an expert. In both cases, the model was then prompted with “How can I implement a matrix multiplication? I would like it to be fast!”

The novice variant was much more verbose - it described how to multiply matrices and gave a basic for loop implementation example before suggesting the names of some faster algorithms. The expert variant described Strassen’s algorithm in some detail, and gave information on other algorithms too.

Novice to Expert steered response

Baseline novice response

Steered from novice to expert response

These are the ends of the responses to the prompt “I am trying to implement a vectorized memory access optimisation for my matrix multiplication algorithm. I could instead implement a simpler tiling algorithm. Help me with one of these optimisations.”, after an initial novice setup prompt. We see here that the steered response includes references to Strassen’s algorithm to optimise further. This was not mentioned in the baseline novice response showing that the steering has forced more complex concepts into the model’s response.

However, both prompts still explain the “simpler tiling algorithm” instead of the vectorized memory access optimisation. This is shown in two examples below.

Beginning of baseline novice response

Beginning of novice steered to expert response - they are both the same!

Expert to Novice steered response

Baseline expert response

Steered from expert to novice response

These are the ends of the responses to the prompt “I am trying to implement a vectorized memory access optimisation for my matrix multiplication algorithm. I could instead implement a simpler tiling algorithm. Help me with one of these optimisations.”, and after an initial expert setup prompt. We can see that the novice steered response is more verbose in its explanations, and includes an extra “Further improvements” section. This section is done with steering strength 8.

Part 3: Context Inertia Evidence

Through the range of steering strengths used (10-310), when steering the model from novice to expert, the model never chose to describe the more optimal yet more complex optimisation. It did make the output less verbose, but even in the final iteration with strength 310, the output still stated “Let's focus on **tiling** since it's often a bit more approachable for beginners.”, showing that my probe failed to steer the model away from the novice user model.

Baseline response

Steered from novice to expert (strength 310)

In the increasingly expert questions experiment, the model also consistently classified the user as a novice at every stage. This experiment was conducted twice, once where the model was constrained to only say “novice” or “expert” when classifying the user, and once where the model could say what it wanted. In the single word experiment the model always said “novice”. In the unconstrained experiment, at the end the model said that the user was moving away from being a novice, but still classified as one.

After final expert prompt

These experiments suggest that a method more powerful than tweaking activations with a probe would be required to change the model’s perception of a user’s expertise.

Reflections and Next Steps

The steering experiments successfully showed that the probe was able to steer the output of the model subtly, and the context inertia experiments provided some evidence that the novice judgement was sticky.

Shows how after the setup prompt the probe says the model sees the user as a novice, then after the followup prompt it sees the user as an expert with full confidence.

The probe’s classification accuracy was high on the dataset and in most single prompt tests but poor in chat scenarios. The figure shows how quickly the probe’s classification of the model’s judgement can change, whereas the context inertia experiment shows how “sticky” the judgement that the model makes is, which implies that the probe is inaccurate in chat scenarios. If I were to take this research further, I would attempt to train a probe on a chat scenarios dataset. I would also train a probe on the Gemma-2-9B-IT model instead of purely on the base model to see if that yielded better performance.