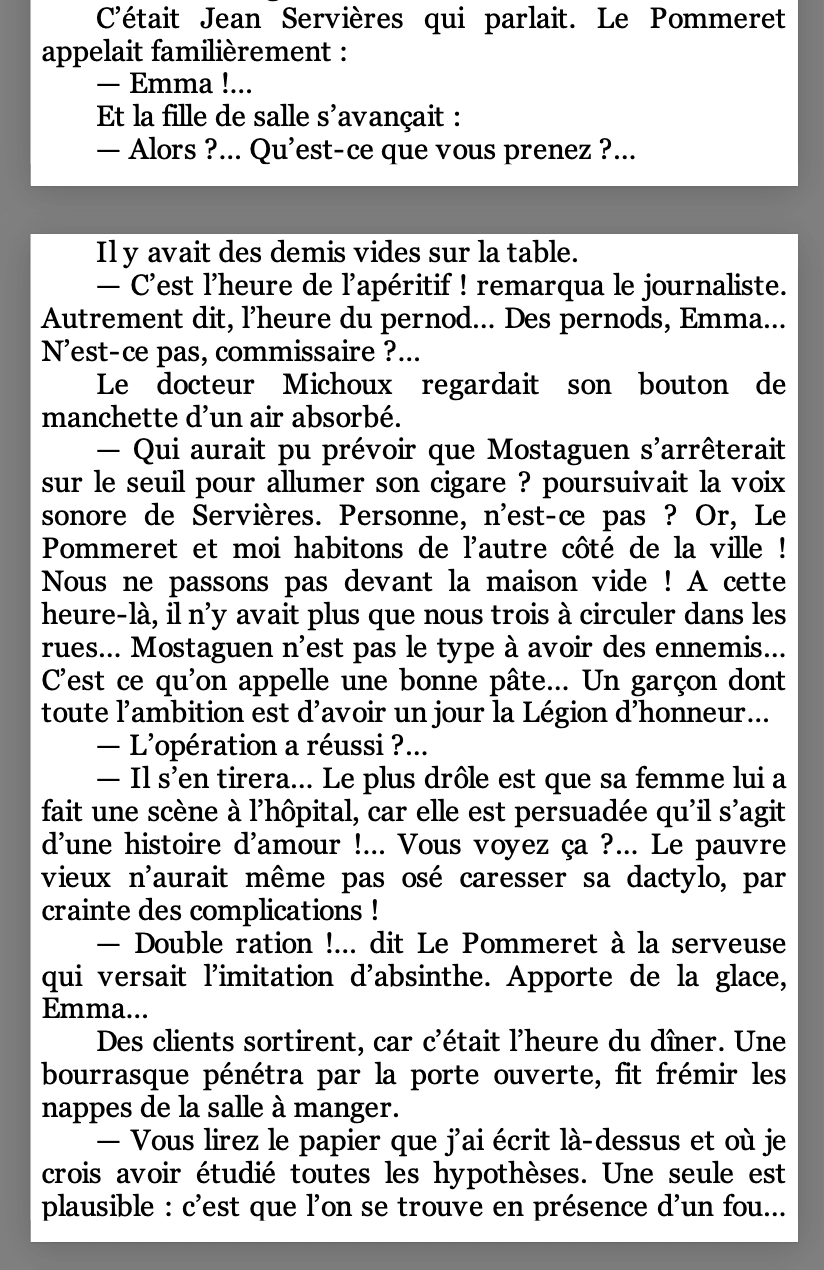

Other languages have different conventions. In French, dialogue is usually indicated by a new line and a dash. Within a paragraph it need not be typographically distinguished from the non-quotation text: for example, the phrase "poursuivait la voix sonore de Servières" in the paragraph below beginning "— Qui aurait".

To me it's like reading the dialogue of a silent film.

I believe that in Trump’s linguistic mind (and make no mistake, he is one of the most interesting linguistic minds of our day, and I’ve thought this for ten years now, even back when I was voting for his opponents), there are nouns, proper nouns, and Important Nouns. How to give emphasis to this new class of Important Nouns? In speech it’s easy, and you hear it in his voice when he speaks, this emphasis (or anyone’s voice, emphasizing the important nouns in a sentence is a very common element of speech); but in writing it’s not clear how to do it.

This capitalization of "Important Nouns" thing isn't particularly unique to Trump. I've used it for a long time in my own writing, I recall it being A Thing in 2015-era Tumblr, and Eliezer uses it quite a bit in the sequences too (Ex. last paragraph of The Bottom Line). It seems pretty widespread to me honestly.

I think "Important Nouns" is not quite the right description, and that its use (in all these cases) is more about something like invoking a more specific concept than the nouns would normally imply. And yeah, I think this is a standard part of spoken English which people intuitively write by capitalizing like this.

I associate the Important Nouns with the Winne-the-Pooh stories, where they are used for a certain humorous effect.

Christopher Robin was sitting outside his door, putting on his Big Boots. As soon as he saw the Big Boots, Pooh knew that an Adventure was going to happen, and he brushed the honey off his nose with the back of his paw, and spruced himself up as well as he could, so as to look Ready for Anything.

It does suggest something like a specific concept, a recognized pattern; while also suggesting perhaps a pompousness and self-importance.

It’s odd - a friend messaged me after reading to say he did the same thing, yet Dickinson analysts are either mystified or in denial that the caps mean anything at all; and the only articles I could find on Trump’s casing found it very odd indeed and were similarly mystified (though they were low-effort output articles at major news organizations, not analysis). So I am hearing only that it’s super weird or that it’s quite typical, nothing in-between!

I don't really expect academic analysts or journalists to be on top of noticing "heretical grammar" in common usage,[1] and I suspect that the articles about Trump's usage are intended as dunks on him.

I bet if you pay attention you'll see it fairly regularly! (In posts, comments, and blogs... probably not so much in things like Wikipedia or the NYT.)

- ^

Geoff Lindsey has lots of videos about academic blindspots like this in phonology (but to be fair, he is an academic himself). The pattern seems to be that the received wisdom gets ossified, and then people in the field don't even notice that they need to update. I suspect this is pretty common in any domain where there are epistemic authorities people prefer to defer to.

But then we have to ask — why two ‘ marks, to make the quotation mark? A quotidian reason: when you only use one, it’s an apostrophe. We already had the mark that goes in “don’t”, in “I’m”, in “Maxwell’s”; so two ‘ were used to distinguish the quote mark from the existing apostrophe.

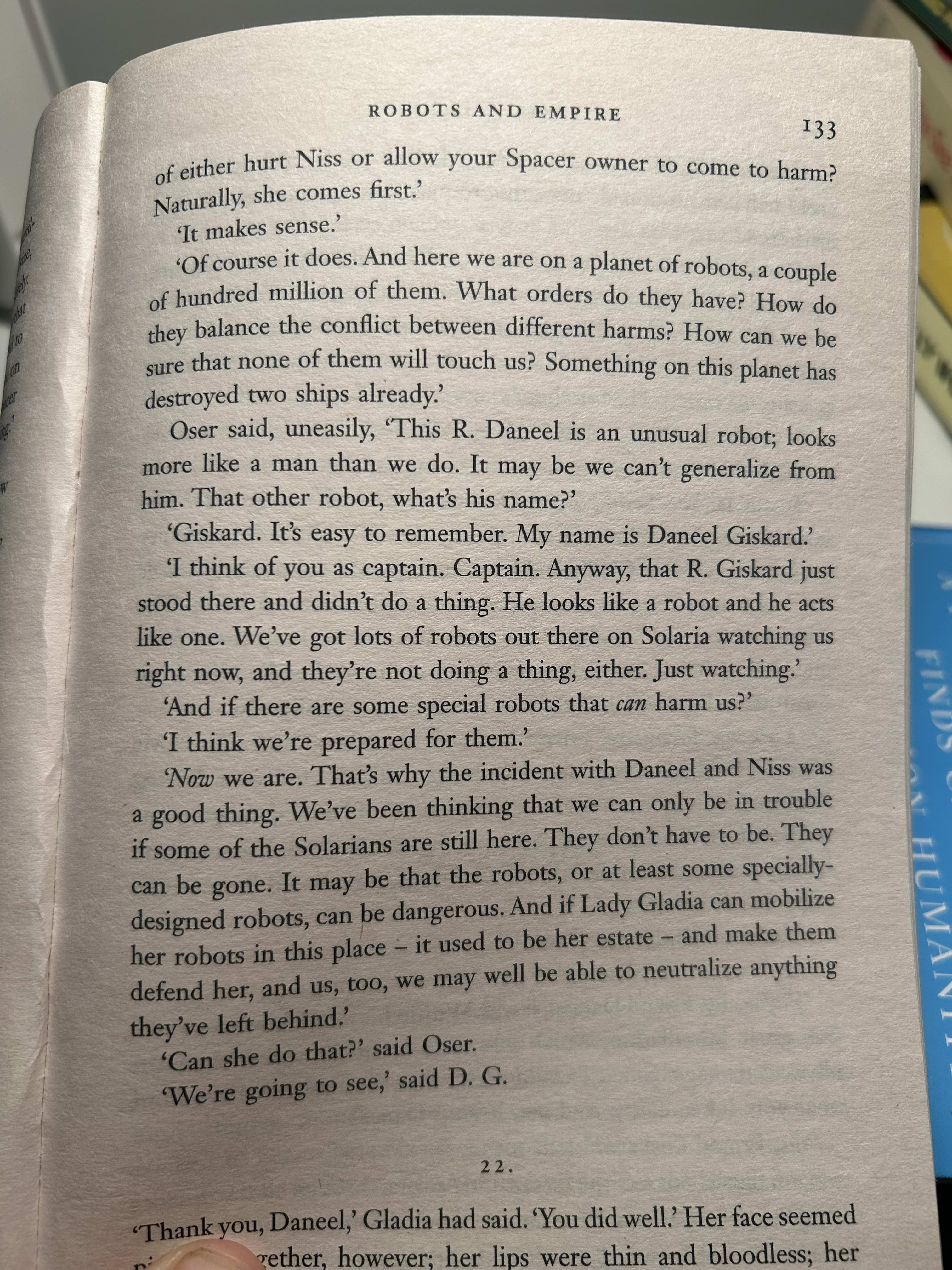

Incidentally I think in British English people normally do just use single quotes. I checked the first book I could find that was printed in the UK and that’s what it uses:

When I was a child in school, punctuation marks were taught like rules. A period goes at the end of a sentence. A comma is useful because a list like “Apple banana cherry” is wrong; the list “Apple, banana, cherry” looks better. If you don’t use commas or periods or ‘and’ or ‘but’ enough, but simply write the things you want to write without bothering with demarcation, you get a run-on sentence. Some words should start with a capital letter everywhere; also the letter at the beginning of a sentence should be capitalized. Semicolons; hyphens and dashes; ellipses. Parentheses. Forward-slashes.

It makes sense to teach them to children as rules, first, and of course they do have rules attached to them. One may talk of expression and experiment, but nothing ever justifies using a parenthese her)e. But at the same time, there is wonderful flexibility in which you choose to use where. Consider the following examples.

He was going to be late again (and again no one would notice).

He was going to be late again; and again, no one would notice.

The parentheses version makes it seem like the subject is getting away with something unimportant. I’d use it if I were writing about a man who, say, has a flexible office job, where you can arrive whenever.

The semi-colon-comma version has more weight; I’d use it about a man who, let’s say, was having trouble with his family. Perhaps he arrives late to dinner, and they barely even notice or care. A heavier situation, so the heavier version of the sentence works better.

The former, confidently dismissive. Spoken by someone in control. The latter, flummoxed, unsure. A debater who knows his opponent has just gotten one over on him in front of everyone. A cheating spouse, after evidence has been discovered. Ellipses - just a group of periods, really - and dashes, used to evoke the pauses of speech that can happen when communicating orally. The confident / unconfident difference is also present in this contrasting pair:

Trump Case: the idiosyncratic capitalization choices made by Trump when he writes. Examples are absolutely everywhere; here’s a Truth Social post of his from a couple hours ago[1]:

All-caps emphasis is common enough, but Trump Case is fun and unusual. Farmers get a capital letter to start with, so does Country; Tariffs too. But it’s not like he capitalizes every noun: ‘money’ isn’t capitalized, and in longer excerpts there are plenty of uncapitalized nouns.

Compare to normal-case:

I don’t fully understand the choices made when doing Trump Case, but maybe “soybean farmers” seems a little random here when normal casing? Promoting them to Soybean Farmers gives a little bit of oomph - it makes them a class, a people, rather than the word ‘farmers’ modified by an adjective.

I believe that in Trump’s linguistic mind (and make no mistake, he is one of the most interesting linguistic minds of our day, and I’ve thought this for ten years now, even back when I was voting for his opponents), there are nouns, proper nouns, and Important Nouns. How to give emphasis to this new class of Important Nouns? In speech it’s easy, and you hear it in his voice when he speaks, this emphasis (or anyone’s voice, emphasizing the important nouns in a sentence is a very common element of speech); but in writing it’s not clear how to do it.

So: you want to write the above quote (the normal-cased version) while emphasizing some nouns and not others. There are other ways to do it; perhaps by saying more about why soybean farmers are important, and allowing the term to appear twice at the beginning:

This is perfectly fine, there’s nothing wrong with it. Trump Case is cool because it’s a character-level way of aiming for the same thing. So now we can see too that - like the parenthese, comma, semicolon - capitalization is not just a set of rules you can get wrong - “you must capitalize the first character of a sentence, as well as proper nouns” - but also a modifiable element that can be used to transmit different meanings by using different capitalization choices.

Emily Dickinson was another syntactical idiosyncratic. Dashes meant things to her that were quite unclear to others, and the first publishing of her work (which happened only after she died) removed most of the dashes, in favor of semicolons, commas, and periods. This first dash-impoverished version was prepared and published by two of her friends, and it is wonderful that they did so - if they hadn’t, likely none of us would have heard of Emily Dickinson. They gave us a wonderful gift.

But god, what butchery! The dashed versions - the one Dickinson intended - look like this one (original):

But this poem in 1890 was published as:

In the 1890 editing, the meter is off, the musicality badly damaged. (And even what I am calling the “original” is badly chained by the demands of Type. Dickinson wrote her poems by hand, and her dashes varied in length and in angle; Typographers have only a handful of dash characters to choose from).

But the musicality. If you don’t see it, try focusing only on the difference between

and

Read them in your head, or say them aloud, and you see: these are different.

Incredibly - and I swear I did not know this, I am researching this essay as I write it, I did not know this, I literally wrote the entire section on Trump Case, then thought “what other examples can I give” and remembered Dickinson’s dashes, and went to her poems only to talk about the dashes — and yet — it may be that the only other prominent user of what I called “Trump Case” was ——— Emily Dickinson!

Look at the original poem again:

Time and Anguish get capitals - but schoolroom, sky, woe, these nouns do not. There is even an instance of lowercased anguish!:

Thinking about it, it makes sense why “each separate anguish” deserves less emphasis - it refers to a broad category of anguishes that Christ is explaining in the schoolroom. The drop of Anguish, though - scalds her now. So even someone like you or I, who would rarely or never use capital letters in this way, can see that it makes more sense to capitalize the one she did, and why it would seem off to capitalize the first ‘anguish’, but not the second. There’s meaning there. The poem is different if you change it; the choices matter.[2]

Even for line breaks - things that basically just exist because the materials we write on and read from have finite width - the choice of where to put them carries meaning and feel. Edward Tufte, in his 2020 book, gives an example of two ways to write the words of Miles Davis:

Tufte makes a number of improvements in the second writing: italics work well here, lowercasing everything does too, but the critical change is the line breaks. Every time a line breaks just before a pause, it’s a tiny loss. Even in the sentence I wrote at the beginning of this section:

doesn’t work well! It should be

but some of you will read this on desktop and some will read it on mobile

so there’s nothing to be done.

I love how different these contrasting examples feel - the difference between No. and No!, the superiority of dashed Dickinson over edited Dickinson, the odd subtle shifts in meaning that occur when you write The Soybean Farmers of our Country instead of the normal-cased version; the line breaks. There is so much of this stuff. It is one of the main joys of writing, the mental cycling I do through all the ways I could write a sentence, the difficulty of settling on one, but also sometimes the feeling that the sentence I wrote could not be written in any other way without ruining it. Semicolons, commas, capitalizations, whether to use a dash, the length of that dash, it is all so rich.

Except for the quotation mark.

The quotation mark is a dead symbol. Inflexible and inert. It can be used in perhaps three ways:

In this use the quotation marks act like hyphens - it’s very similar to

another kind of demarcation was when I wrote

You couldn’t use hyphens to demarcate there. You could use line breaks, but using quotes keeps the sentence compact.

The above usage types are useful, and I’m glad they exist. The issue is that there’s no interesting way to vary how the quotation mark is used. All the variance in how a quote or conversation feels, in text, is accomplished by the other punctuation marks. In this example fragment from the story Claw, one character is driving, the other is talking to them over the phone.

Just a few changes to punctuation and font changes Carson’s tone from straightforward to confrontational:

There are lots of things like this you can change in any sentence, but the quotation marks are never one of them. It is just tragic that the

“can not be modified to carry any additional information beyond its bog-standard use. Even when a modification to the entire quoted line is desired:This line is spoken over the phone, and the author wants to make it clearer this speaker is on the other end of a phone call. So he uses italics. Very reasonable choice - but it feels like something the quotation mark could, theoretically, could do, in a world different from ours. A “phone-quote” mark, perhaps, instead of a basic quote mark? ‘‘‘ instead of “? Maybe part of the issue is that it isn’t easy for the eye to see the extra ‘ in ‘‘‘. The eye can distinguish the

. , ;triplets easily, but my eye stutters on counting how many ‘ there are in ‘‘‘‘‘.But then we have to ask — why two

‘marks, to make the quotation mark? A quotidian reason: when you only use one, it’s an apostrophe. We already had the mark that goes in “don’t”, in “I’m”, in “Maxwell’s”; so two‘were used to distinguish the quote mark from the existing apostrophe.But… why choose a mark that needed to be distinguished from

‘in the first place? Did we run out of shapes? We have a punctuation mark that’s just two already-existing ones in a row, really? Some other symbol entirely should have been used! It makes me wonder if quotation marks were a late invention, only thought up after the typewriter was invented, and society had already committed to a fixed set of characters.[5]The way that, to change the meaning in Carson’s sentence to Nathaniel above, every piece of punctuation except for quotation marks can be usefully varied, also suggests a situation where quotation marks arrived late to the English language: all the meaning-variation was already taken, so the quotemarks had to settle for a static and fixed role.

My favorite solution to this problem - that in a story, the standard rules of English demand you put these inert static marks everywhere, that catch the eye but always mean the same thing and are therefore uninteresting - my favorite solution to this is in the writing of Delicious Tacos:

His solution is to rip them out, delete them all! They weren’t doing enough. He deigns to use them once, but for the title of a Reddit post. The standard version is not better:

One objection that could be made here is, well, this is mostly rapid back-and-forth conversation, so the quotes can be dropped here; but in a text that has lots of description, with conversation interspersed, the quotes are necessary to distinguish the narrative description from the things the characters are saying. And perhaps that’s true, but once an author has used quotation marks for conversation in one place, they feel bound to use them everywhere. Claw is a book with tons of description, as well as plenty of conversation interspersed, but rapid back-and-forths exist there too:

Does this work without quotemarks?

It doesn’t feel like it works. In particular, the final line where Mia takes a note is difficult to distinguish as being separate from the conversation. So getting rid of quotation marks means you then have to demark things-that-are-spoken from things-that-are-not-spoken in different ways. The top two ways are

1) phrases like “he said,” and

2) line breaks.

These two things alone go most of the way toward being able to get rid of the quotation mark in written conversation, and still keep things clear. The frustrating thing is that both are still usually necessary when using quotemarks! Read anything with quoted conversation: He saids are still all over the place, each character’s speech still gets its own line break. So even this very heavy punctuation mark - twice the size of an apostrophe - still requires clarifiers. Multiple redundancies just to make it clear someone is speaking. Perhaps this is just that difficult of a problem? Maybe clearly denoting who is speaking what is fundamentally difficult, and no system could solve it cleanly?

That a quote must be closed, even when nothing else is on the line, is also a bother. We are all so used to quotation marks by now that what I’m about to suggest offends the eye, and is not a real suggestion, but if a line is entirely quote, why use a symbol that must be closed later? Instead, just mark the line once at the beginning:

The > is a little too large for this purpose, I’d like a lighter mark, but you see what I mean - the lines where nothing comes after the words being spoken do not need a closing “, where the lines that are mixed (“Okay, Nathaniel,” Carson said. “I’m going to ask you some questions) do.[6] But the need to still use “ in some places means using a single-marker like > is not a clean solution either.

So I don’t know what to do. Perhaps there is nothing to be done. I only wanted to share my pain.

A couple hours before I wrote this line, I mean. Not a couple hours ago for you.

People understand Dickinson’s casing about as well as they understand Trump’s. The best the Emily Dickinson Museum’s website can do is

There have been arguments that there was no meaning to be found at all in Dickinson’s capitals; R.W. Franklin makes fun of people like me, who consider Dickinson’s capitals as carrying meaning, by pointing out a recipe she wrote down:

[More in Denman 1993, Emily Dickinson’s Volcanic Punctuation]

Not understanding this type of usage can cause issues - I have seen many an immigrant storefront advertising

The cast-doubt usage of quotation marks have the distinction of being the only punctuation mark to have broken containment, jump off the page, and enter the language of oral communication: The air quote.

You may say, well, a

;is just a.on top of a,. But that’s perfect! because a;is less of a stop than.but more of a stop than a,— whereas the“symbol used for quoting has no such relation to the‘used for combining “do” and “not” into “don’t”.I don’t actually suggest the > for novels or anything, but it is already in use as a quotemark in some places. Here on LessWrong, on desktop, typing a > creates a quoted section (with the little left sidebar), but on mobile (for me), the > does nothing and just appears as a >. I still use in when quoting someone I’m speaking with, though, especially when disagreeing or arguing, because it’s safer than “.

This is because the “ mark’s use as a quoter can conflict with its use as a “this is stupid” marker. Recall that a line like

intentionally disrespects the subject. If I’m disagreeing with someone online, especially on a fraught topic like politics - for example if they say “The president’s choice of sandwich at McDonald’s is suboptimal” - if my responding comment is something like

It can sometimes look like I’m using the quote marks to make my opponent sound stupid. But > does not have this connotation, so quoting them with > instead

is generally safer. No one has ever used a > in a sentence like “Last year’s >winner is still very proud of himself”, so there’s no possibility of confusion.