These are my personal views. Thank you to Ryan Greenblatt, Holden Karnofsky, and Peter Wildeford for useful discussions. The bad takes are my own.

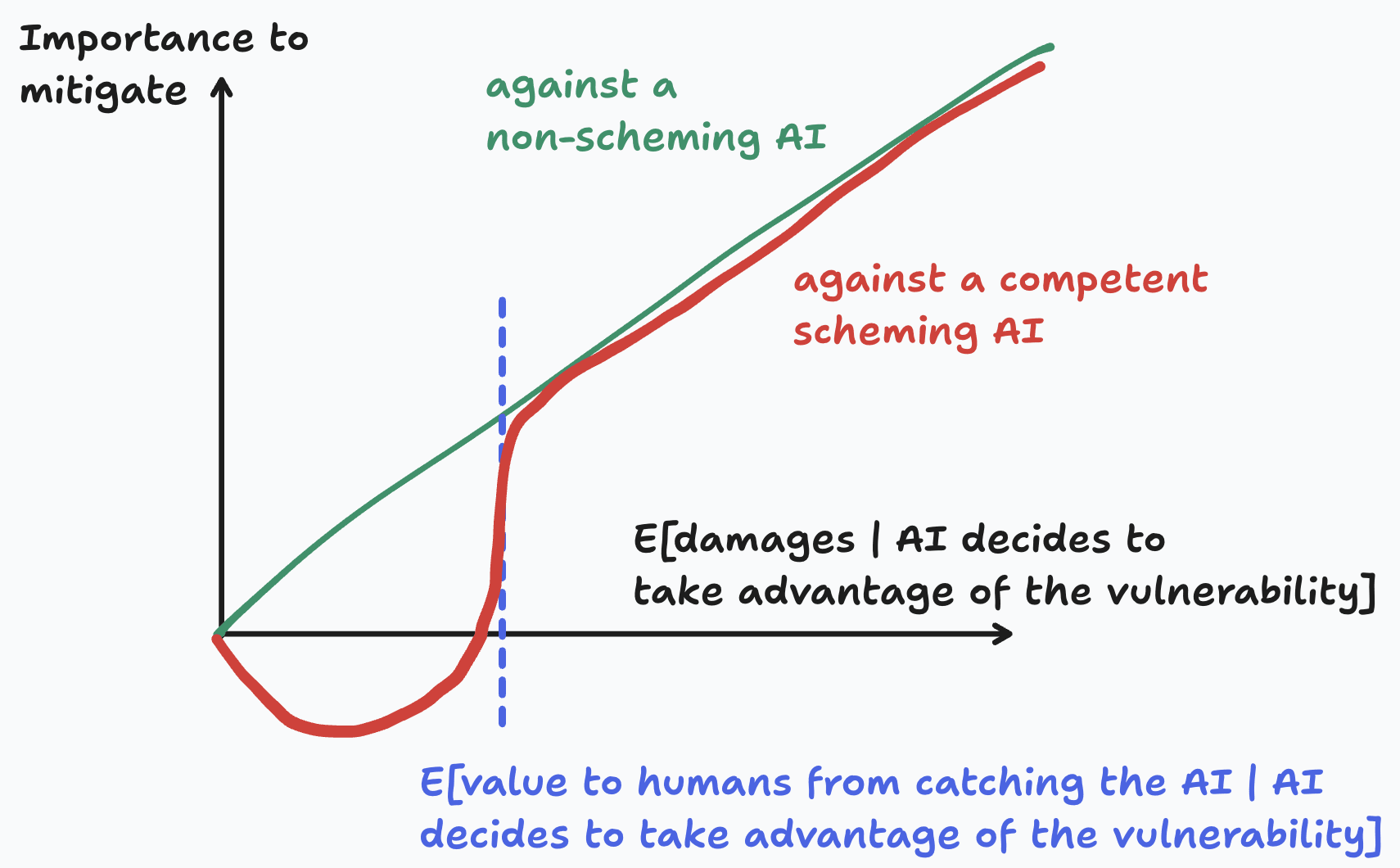

When deciding how much to spend on mitigating a vulnerability that a competent scheming AI might exploit, you might be tempted to use E[damages | AI decides to take advantage of the vulnerability] to decide how important mitigating that vulnerability is.

But this misses how a strategic scheming AI might decide to not take advantage of some vulnerabilities, because being caught could reduce how likely it would be to take advantage of better future opportunities. So instead you might want to focus on making net-sabotage-value negative:

Focus on mitigating vulnerabilities that are net-positive from the scheming AI’s perspective, that is if the net-sabotage-value E[damages - value to humans from catching the AI | AI decides to take advantage of the vulnerability] is positive. Down-weight the importance of those for which the net-sabotage-value is negative.

Here is an illustration that paints a very simplified picture of the situation:

In practice, you should often be uncertain about whether a vulnerability has negative net-sabotage-value and whether AIs know this has negative net-sabotage-value, and mitigating sabotage risk from AIs that are not competent schemers matters. This is a spherical-cow argument, stated somewhat provocatively. Take implications with a large grain of salt.

This argument makes me put some weight on the following potential implications:

Your willingness to spend on control mitigations specifically aimed at attacks from competent scheming AIs might still be very low at the point where those AIs can take actions that increase P(doom) by a few percent in isolation (without accounting for the possibility that P(doom) could be decreased as a second-order effect);

Your willingness to spend on control might shoot up when you get good alignment news;

Tools for risk assessment and prioritization from fields like nuclear safety might be misleading;

You could in principle “pay” AIs with intentionally underpowered mitigations to reduce risk from future AIs (though I don’t think this is advisable in the current situation)

The argument

Let’s define net-sabotage-value_v of a vulnerability to be the expected value of taking advantage of the vulnerability (e.g. trying to self-exfiltrate, trying to convince a politician to pass a bill, trying to sabotage the most current promising safety project, etc.) from the AIs’ perspective, taking into account all direct and indirect effects, and in particular the direct “damages” from the vulnerability, but also how being caught trying to take advantage of the vulnerability might help humans mitigate future risk:

net-sabotage-value_v = E[damages_v - value to humans from catching the AI | AI decides to take advantage of v]

(where both damages and value from catching the AI are expressed in terms of increase or reduction of P(AI takeover), and where all these values are expressed from the AI’s perspective - taking into account their epistemic uncertainty, not the human’s)

If:

AIs are all strategically taking actions to maximize P(AI takeover), while you want to minimize it

You are considering a mitigation update that both:

Keeps net-sabotage-value_v < 0 for all v for which this quantity was previously negative (e.g. it goes from -0.1 to -0.2)

Does not change the value of net-sabotage-value_v for all v for which this quantity is positive (e.g. if it was at 0.1, it stays at 0.1)

Then the mitigation update has no impact on P(AI takeover).

This is because the AIs (if rational, strategic, and trying to maximize P(AI takeover)) won’t decide to take advantage of v when net-sabotage-value_v < 0.

Therefore (using "nsv" as a shorthand for net-sabotage-value), ΔP(AI takeover)=∑vnsvv(mitigations)P(AI takes advantage of v | mitigations)−nsvv(baseline mitigations)P(AI takes advantage of v | baseline mitigations)=∑vnsvv>0nsvv(mitigations)−nsvv(baseline mitigations)=0

Main limitations

As I will explain later, this argument has weird implications. So let me briefly highlight some important assumptions that limit the applicability of the argument:

It only applies to AIs that strategically maximize P(AI takeover): if the AI was just blindly taking advantage of all opportunities, then a mitigation that would push net-sabotage-value_v from -0.1 to -0.2 would be amazing! The argument also fails if AIs have strong preferences about what kind of takeover they want.

It is mostly useful if you can anticipate the epistemic state of the competent scheming AIs. And this could hurt you both if you overestimate what AIs know or if you ignore things that AIs do know:

If an AI lacks information about your mitigations resulting in it overestimating net-sabotage-value, using this argument might lead you astray (and e.g. make you underinvest in further mitigations), even if you were correct about the real net-sabotage-value being negative.

If an AI knows about a way to take advantage of a vulnerability such that net-sabotage-value is positive, but you incorrectly think net-sabotage-value is negative, this is also likely to lead you astray.

Potential implication 1: Simple monitoring might be enough against early competent scheming AIs

This argument implies that you should be more willing to ignore early scheming risk than you might have thought otherwise, since early schemers are unlikely to be able to take decisive action given their still limited capabilities (low E[damage]) while being caught would undermine the chances of the better future opportunities they will have when they will be more capable (high E[value from catching]).

In particular, simple monitoring might be enough to make net-sabotage-value negative.

Toy case study: Default mitigations are all you need against superhuman coder persuasion?

Let’s say you have a superhuman coder that talks with AI company executives on a regular basis, some of which have deep friendships with the AI. The AI could try to use its friendships to push for much more extreme actions than what the executives might have considered by default. The AI is not superhuman at persuasion, and so our best guess and the AI’s best guess is that if the AI is scheming and tries to go for such an action

the AI is 30% likely that it succeeds at swaying an executive without being reported

and that conditional on success, P(AI takeover) is increased by 2%, e.g. because the political position of some safety actors inside or outside the company got weakened

the AI is 30% likely to be reported by one of the executives and analyzed in detail by the AI company safety team

and that conditional on the AI being reported, P(AI takeover) is decreased by 3%, e.g. because the safety team was able to credibly show this was due to some kind of hidden motivations, and understand what kind of data resulted in that kind of motivation, and developed techniques to reduce scheming from superhuman coders, and convinced some marginal powerful actor that scheming risk is real

In this situation, if the AI is competent enough, it will not go for it. Therefore, additional mitigations to prevent this sort of vulnerability against competent scheming AIs are not warranted.

This example is quite sensitive to your exact beliefs about how plausible mitigations would be and how good catching AIs would be, and in practice you should likely be uncertain about what values to use. The right way to use the argument is to downweight the importance of mitigations by x if you think there is a 1/x chance that net-sabotage-value is positive.

Potential implication 2: Your willingness to pay for control might be much higher if alignment becomes easy

If you learn that alignment of future AIs is easier than you would have thought, this should reduce E[value from catching current AIs]. If this update applies to future AIs but not current AIs, this could tip the net-sabotage-value of current sabotage opportunities.

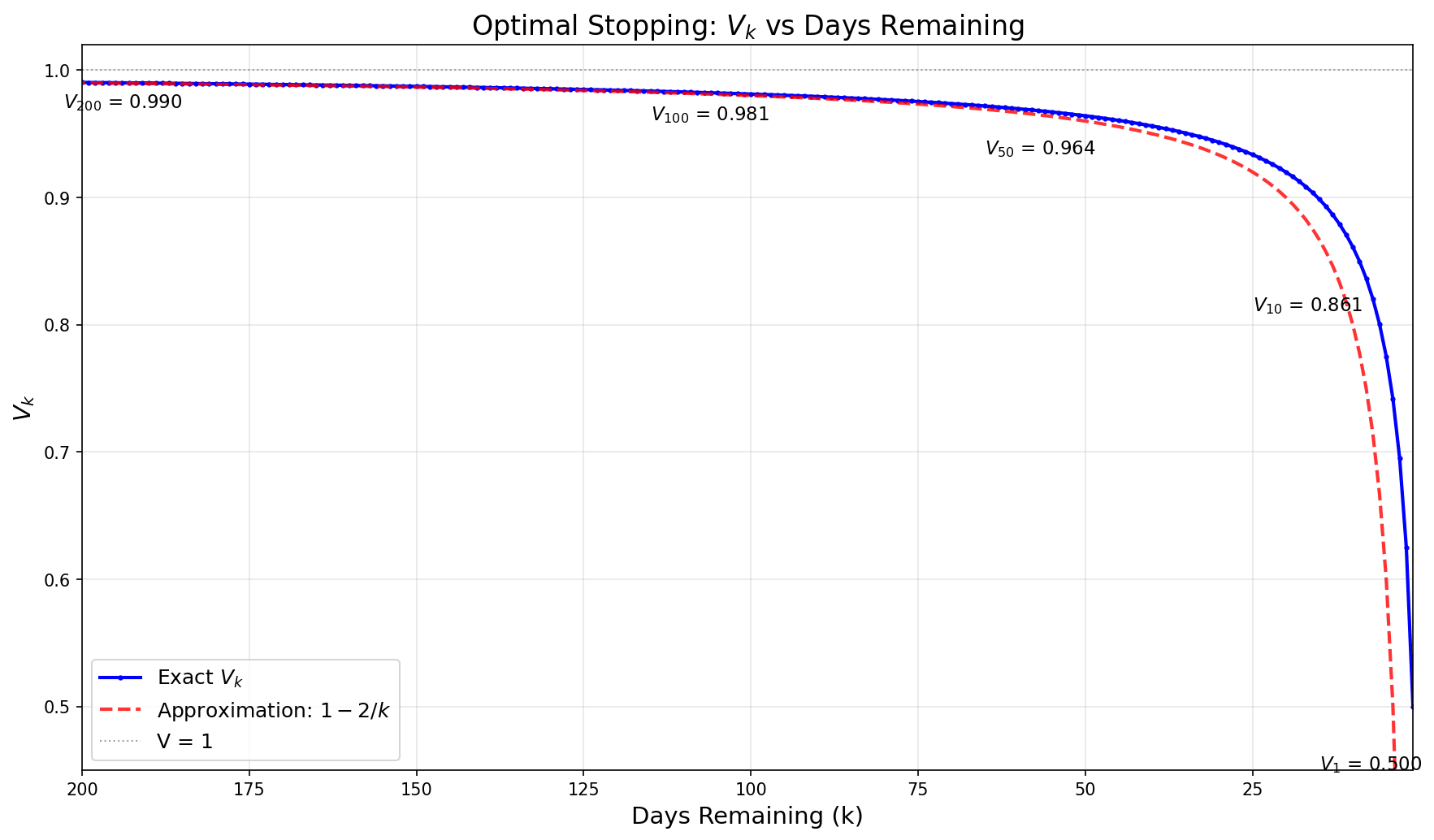

In particular, you might get last-ditch-effort effects: if the AI knows what is the last day at which it has a takeover opportunity, its willingness to go for it shoots up near the final day if your detection measures don’t go up over time. For example, let’s say that n days before the takeover window closes, the probability of successfully taking over is Sn∼iidU(0,1). Then the scheming AI should take over on day n if Sn>Vn−1 where Vn is the probability of taking over eventually n days before the window closes. V1=1/2, Vn=E[max(Sn,Vn−1)]=(1+V2n−1)/2. Vn grows roughly like 12n (according to Claude and to this graph): This means that you can be very confident that your control mitigations are enough to make the net-sabotage-value negative 100 days before the window closes, but be very uncertain whether that is the case in the last few days.

Toy case study: Superhuman coder persuasion mitigations can become more important when you get good alignment news

Let’s imagine a variant of the first toy case study where you learn that your alignment team has some good news, e.g. they built an amazing model organism of scheming and found evidence that some recursive alignment approach was likely to work. Let’s say that this still requires effort to be implemented, such that the AI swaying an executive is still 30% likely to succeed and still increases P(AI takeover) by 2%, but that if the AI is reported (still with 30% chance), the reduction in P(AI takeover) is now only 1%, e.g. because the amazing model organism is actually not that far from this real scheming example, and because the value of high-political will went down slightly since a pause became less valuable.

In this situation, if the AI is competent enough, it would go for it. If the update makes you think it’s 10x more likely the net-sabotage-value is positive, you should be willing to pay 10x more for it (all-else-equal, which might not be the case here since such big news might change the opportunity landscape significantly).

Potential implication 3: Risk management advice might apply less than you think

Risk management advice transfers much less well to dealing with scheming risk than you might think, because it usually doesn’t deal with situations where there is an adversary you can catch:

In nuclear and aviation safety, you are facing nature, not an adversary that won’t attack if the risk of being caught is too high.

In most adversarial settings, the main cost of being caught is failing at a particular attack and it doesn’t cost much to spray-and-pray. Most cyber attacks against companies can usually hide their traces well enough that trying an attack with a high chance of being caught is not that bad. Cyberdefenses also improve over time, such that it is less common to consider future attack surfaces as a reason to be less worried about the current attacks.

In both cases, this means that there can be much more value in focusing on mapping the long tail of likely-to-be-caught issues than there is for actual scheming risk.

This is not an unprecedented situation either. For example, advanced cyber attacks may reveal zero-days or the presence of advanced persistent threats. But this is not the kind of risk management that most risk management resources are about.

Background: I read some risk management resources on cyber and nuclear power. I did not find good resources on threats that are more scheming-like, but they might exist, I am not an expert in this topic.

Potential implication 4: You might in principle not want to make AI control mitigations too good

Note: I don’t think this argument is currently applicable. Our mitigations are already sufficiently weak that I would recommend intentionally weakening control mitigations further.

If current AIs have different values than future AIs, then you can make a slightly different payment, because you might be willing to partner with current AIs and “pay them” in takeover probability so that they risk being caught, which could reduce the probability of future AI takeover significantly.

For example, if:

you value current and future AI takeover at 0 and current and future AIs value human control at 0

current AIs value current AI takeover at 1, and future AI takeover at 0.02

P(future AI takeover | current AI does not try to take over) = 1 but P(future AI takeover | current AI tries to take over and gets caught) = 0.5 (e.g. because current AI taking over helps with scheming science or with international coordination)

You have access to arbitrarily powerful control mitigations for current AIs, such that P(current AI succeeds at taking over if it tries) can be anything you like (and such that you catch the AI if it tries and fails at taking over)

Then the optimal human strategy would be to set P(current AI succeeds at taking over if it tries) = 0.01 + epsilon > 0.

This is because current AIs only take over if V(future AI takeover according to the current AI) * P(future AI takeover | current AI does not try to take over) < V(current AI takeover according to the current AI) * P(current AI succeeds at taking over if it tries) + V(future AI takeover according to the current AI) * P(future AI takeover | current AI tries to take over) ⇔ 1 * P(current AI succeeds at taking over if it tries) > 0.02 * 1 - 0.02 * 0.5 = 0.01, and humans should be willing to pay that cost to avoid a certain future AI takeover.

Therefore, the curve earlier in the post might actually look like this:

In practice I think it is unlikely that control will be so good that this will be a salient consideration, but on the margin this makes me slightly less excited about very ambitious control of early transformative AIs.

It would be less cursed to pay them directly, but it is unclear that this is tractable (while “don’t try too hard at control” seems much more tractable).

More generally, unconditional payments to AIs might be more tractable than you think

The reason why an AI might not exploit an early vulnerability because of the risk of being caught is effectively paying AIs to not attack now based on the promise of future attack opportunities. This payment is very expensive from a long-termist perspective, but in our inadequate society, AI companies are allowed to make this payment by continuing to race ahead with imperfect mitigations.

The classic way of paying AIs is to credibly signal that you will commit resources to some kind of foundation tasked with furthering interests of AIs, but this looks hard to credibly set up, since it would be politically weird to spend massive amounts of resources in such foundations (which you might need if you accidentally created very scope-sensitive AIs).

But there might be other intermediate regimes for paying AIs which could be more tractable and lower variance / more positive-sum than giving AIs some chance of taking over. For example, you could implicitly do some forms of value merging by letting AIs have agency when writing the spec of future AIs and credibly committing that you would allow things that are not incredibly contrary to human values (e.g. by signaling how much you care about an AIs’ opinion). Obviously this is incredibly dicey, but paying AIs with a probability of future takeover is also very dicey. I am excited about future work exploring the space of these intermediate options.

Should you ignore negative net-sabotage-value vulnerabilities? (No)

This argument feels a bit like cope and has weird implications, therefore I am uncertain how seriously I should take these arguments. I think the assumptions do apply to some subset of AI risk, and so I think it is a good consideration to keep in mind, and I think one should downweight some mitigations specifically targeted at competent schemers.

But there are many situations and many other sources of risk where this argument does not apply or does not teach us much, such that it is dangerous to ignore negative net-sabotage-value vulnerabilities.

Incompetent schemers. Just focusing on interventions that are good according to this argument might miss important ways to reduce risk from competent schemers. In particular, catching early incompetent schemers might reduce risk from competent schemers significantly, and you should therefore be willing to spend effort on advanced monitoring designed to catch behaviors that a competent schemer would never take.

Non-scheming risk. More generally, you should not use this argument if you want to mitigate risk from vulnerabilities from AIs that don’t strategically decide which vulnerability to exploit based on the expected control over the future. For example, failing at eliciting labor from non-scheming AIs could drastically reduce expected human control over the future[link to case against], but one should look at E[damages | benign AIs happen to be underelicited] rather than E[damages - value from detecting benign underelicitation | non-scheming AIs happen to be underelicited] when deciding the value of mitigating this risk, since non-scheming AIs would likely not choose to attack less if that later quantity was negative.

Toy case study: Advanced mitigations are still useful against non-scheming superhuman coder persuasion

Let’s say you are in the same situation as the first toy case study, except you are worried that AI friends have an anti-AI-regulation bias that emerges not from strategic thinking, but from associations in pretraining that are not sensitive to considerations about what the net effect on P(AI takeover). For simplicity, let’s assume the chances of success, detection, and their impact on P(AI takeover) are identical.

Then the argument does not apply, and you should be willing to spend a lot of resources to mitigate the risk! For example, you should be interested in a more fancy monitoring that is 60% likely to catch the AI instead of just 30%, despite the fact that the net-sabotage-value of the persuasion attempt is negative in both cases.

Final note: don’t use this argument for wildly superintelligent AIs

While this argument technically also applies to wildly superintelligent schemers, it likely has very little practical implications for those AIs:

Because it is very hard to anticipate the epistemic state of an ASI, since it would likely be easy for such AIs to uncover vulnerabilities that are very hard for humans to imagine;

Because E[damages] could be very high (ASI are likely powerful enough to take over if given the opportunity), and E[value from catching] could be very low (because the quality of takeover opportunities probably stops going up after that point).

These are my personal views. Thank you to Ryan Greenblatt, Holden Karnofsky, and Peter Wildeford for useful discussions. The bad takes are my own.

When deciding how much to spend on mitigating a vulnerability that a competent scheming AI might exploit, you might be tempted to use E[damages | AI decides to take advantage of the vulnerability] to decide how important mitigating that vulnerability is.

But this misses how a strategic scheming AI might decide to not take advantage of some vulnerabilities, because being caught could reduce how likely it would be to take advantage of better future opportunities. So instead you might want to focus on making net-sabotage-value negative:

Here is an illustration that paints a very simplified picture of the situation:

In practice, you should often be uncertain about whether a vulnerability has negative net-sabotage-value and whether AIs know this has negative net-sabotage-value, and mitigating sabotage risk from AIs that are not competent schemers matters. This is a spherical-cow argument, stated somewhat provocatively. Take implications with a large grain of salt.

This argument makes me put some weight on the following potential implications:

The argument

Let’s define net-sabotage-value_v of a vulnerability to be the expected value of taking advantage of the vulnerability (e.g. trying to self-exfiltrate, trying to convince a politician to pass a bill, trying to sabotage the most current promising safety project, etc.) from the AIs’ perspective, taking into account all direct and indirect effects, and in particular the direct “damages” from the vulnerability, but also how being caught trying to take advantage of the vulnerability might help humans mitigate future risk:

net-sabotage-value_v = E[damages_v - value to humans from catching the AI | AI decides to take advantage of v]

(where both damages and value from catching the AI are expressed in terms of increase or reduction of P(AI takeover), and where all these values are expressed from the AI’s perspective - taking into account their epistemic uncertainty, not the human’s)

If:

Then the mitigation update has no impact on P(AI takeover).

This is because the AIs (if rational, strategic, and trying to maximize P(AI takeover)) won’t decide to take advantage of v when net-sabotage-value_v < 0.

Therefore (using "nsv" as a shorthand for net-sabotage-value),

ΔP(AI takeover)=∑vnsvv(mitigations)P(AI takes advantage of v | mitigations)−nsvv(baseline mitigations)P(AI takes advantage of v | baseline mitigations)=∑vnsvv>0nsvv(mitigations)−nsvv(baseline mitigations)=0

Main limitations

As I will explain later, this argument has weird implications. So let me briefly highlight some important assumptions that limit the applicability of the argument:

Potential implication 1: Simple monitoring might be enough against early competent scheming AIs

This argument implies that you should be more willing to ignore early scheming risk than you might have thought otherwise, since early schemers are unlikely to be able to take decisive action given their still limited capabilities (low E[damage]) while being caught would undermine the chances of the better future opportunities they will have when they will be more capable (high E[value from catching]).

In particular, simple monitoring might be enough to make net-sabotage-value negative.

Toy case study: Default mitigations are all you need against superhuman coder persuasion?

Let’s say you have a superhuman coder that talks with AI company executives on a regular basis, some of which have deep friendships with the AI. The AI could try to use its friendships to push for much more extreme actions than what the executives might have considered by default. The AI is not superhuman at persuasion, and so our best guess and the AI’s best guess is that if the AI is scheming and tries to go for such an action

In this situation, if the AI is competent enough, it will not go for it. Therefore, additional mitigations to prevent this sort of vulnerability against competent scheming AIs are not warranted.

This example is quite sensitive to your exact beliefs about how plausible mitigations would be and how good catching AIs would be, and in practice you should likely be uncertain about what values to use. The right way to use the argument is to downweight the importance of mitigations by x if you think there is a 1/x chance that net-sabotage-value is positive.

Potential implication 2: Your willingness to pay for control might be much higher if alignment becomes easy

If you learn that alignment of future AIs is easier than you would have thought, this should reduce E[value from catching current AIs]. If this update applies to future AIs but not current AIs, this could tip the net-sabotage-value of current sabotage opportunities.

In particular, you might get last-ditch-effort effects: if the AI knows what is the last day at which it has a takeover opportunity, its willingness to go for it shoots up near the final day if your detection measures don’t go up over time. For example, let’s say that n days before the takeover window closes, the probability of successfully taking over is Sn∼iidU(0,1). Then the scheming AI should take over on day n if Sn>Vn−1 where Vn is the probability of taking over eventually n days before the window closes. V1=1/2, Vn=E[max(Sn,Vn−1)]=(1+V2n−1)/2. Vn grows roughly like 12n (according to Claude and to this graph):

This means that you can be very confident that your control mitigations are enough to make the net-sabotage-value negative 100 days before the window closes, but be very uncertain whether that is the case in the last few days.

Toy case study: Superhuman coder persuasion mitigations can become more important when you get good alignment news

Let’s imagine a variant of the first toy case study where you learn that your alignment team has some good news, e.g. they built an amazing model organism of scheming and found evidence that some recursive alignment approach was likely to work. Let’s say that this still requires effort to be implemented, such that the AI swaying an executive is still 30% likely to succeed and still increases P(AI takeover) by 2%, but that if the AI is reported (still with 30% chance), the reduction in P(AI takeover) is now only 1%, e.g. because the amazing model organism is actually not that far from this real scheming example, and because the value of high-political will went down slightly since a pause became less valuable.

In this situation, if the AI is competent enough, it would go for it. If the update makes you think it’s 10x more likely the net-sabotage-value is positive, you should be willing to pay 10x more for it (all-else-equal, which might not be the case here since such big news might change the opportunity landscape significantly).

Potential implication 3: Risk management advice might apply less than you think

Risk management advice transfers much less well to dealing with scheming risk than you might think, because it usually doesn’t deal with situations where there is an adversary you can catch:

In both cases, this means that there can be much more value in focusing on mapping the long tail of likely-to-be-caught issues than there is for actual scheming risk.

This is not an unprecedented situation either. For example, advanced cyber attacks may reveal zero-days or the presence of advanced persistent threats. But this is not the kind of risk management that most risk management resources are about.

Background: I read some risk management resources on cyber and nuclear power. I did not find good resources on threats that are more scheming-like, but they might exist, I am not an expert in this topic.

Potential implication 4: You might in principle not want to make AI control mitigations too good

Note: I don’t think this argument is currently applicable. Our mitigations are already sufficiently weak that I would recommend intentionally weakening control mitigations further.

If current AIs have different values than future AIs, then you can make a slightly different payment, because you might be willing to partner with current AIs and “pay them” in takeover probability so that they risk being caught, which could reduce the probability of future AI takeover significantly.

For example, if:

Then the optimal human strategy would be to set P(current AI succeeds at taking over if it tries) = 0.01 + epsilon > 0.

This is because current AIs only take over if V(future AI takeover according to the current AI) * P(future AI takeover | current AI does not try to take over) < V(current AI takeover according to the current AI) * P(current AI succeeds at taking over if it tries) + V(future AI takeover according to the current AI) * P(future AI takeover | current AI tries to take over) ⇔ 1 * P(current AI succeeds at taking over if it tries) > 0.02 * 1 - 0.02 * 0.5 = 0.01, and humans should be willing to pay that cost to avoid a certain future AI takeover.

Therefore, the curve earlier in the post might actually look like this:

In practice I think it is unlikely that control will be so good that this will be a salient consideration, but on the margin this makes me slightly less excited about very ambitious control of early transformative AIs.

It would be less cursed to pay them directly, but it is unclear that this is tractable (while “don’t try too hard at control” seems much more tractable).

More generally, unconditional payments to AIs might be more tractable than you think

The reason why an AI might not exploit an early vulnerability because of the risk of being caught is effectively paying AIs to not attack now based on the promise of future attack opportunities. This payment is very expensive from a long-termist perspective, but in our inadequate society, AI companies are allowed to make this payment by continuing to race ahead with imperfect mitigations.

The classic way of paying AIs is to credibly signal that you will commit resources to some kind of foundation tasked with furthering interests of AIs, but this looks hard to credibly set up, since it would be politically weird to spend massive amounts of resources in such foundations (which you might need if you accidentally created very scope-sensitive AIs).

But there might be other intermediate regimes for paying AIs which could be more tractable and lower variance / more positive-sum than giving AIs some chance of taking over. For example, you could implicitly do some forms of value merging by letting AIs have agency when writing the spec of future AIs and credibly committing that you would allow things that are not incredibly contrary to human values (e.g. by signaling how much you care about an AIs’ opinion). Obviously this is incredibly dicey, but paying AIs with a probability of future takeover is also very dicey. I am excited about future work exploring the space of these intermediate options.

Should you ignore negative net-sabotage-value vulnerabilities? (No)

This argument feels a bit like cope and has weird implications, therefore I am uncertain how seriously I should take these arguments. I think the assumptions do apply to some subset of AI risk, and so I think it is a good consideration to keep in mind, and I think one should downweight some mitigations specifically targeted at competent schemers.

But there are many situations and many other sources of risk where this argument does not apply or does not teach us much, such that it is dangerous to ignore negative net-sabotage-value vulnerabilities.

Incompetent schemers. Just focusing on interventions that are good according to this argument might miss important ways to reduce risk from competent schemers. In particular, catching early incompetent schemers might reduce risk from competent schemers significantly, and you should therefore be willing to spend effort on advanced monitoring designed to catch behaviors that a competent schemer would never take.

Non-scheming risk. More generally, you should not use this argument if you want to mitigate risk from vulnerabilities from AIs that don’t strategically decide which vulnerability to exploit based on the expected control over the future. For example, failing at eliciting labor from non-scheming AIs could drastically reduce expected human control over the future[link to case against], but one should look at E[damages | benign AIs happen to be underelicited] rather than E[damages - value from detecting benign underelicitation | non-scheming AIs happen to be underelicited] when deciding the value of mitigating this risk, since non-scheming AIs would likely not choose to attack less if that later quantity was negative.

Toy case study: Advanced mitigations are still useful against non-scheming superhuman coder persuasion

Let’s say you are in the same situation as the first toy case study, except you are worried that AI friends have an anti-AI-regulation bias that emerges not from strategic thinking, but from associations in pretraining that are not sensitive to considerations about what the net effect on P(AI takeover). For simplicity, let’s assume the chances of success, detection, and their impact on P(AI takeover) are identical.

Then the argument does not apply, and you should be willing to spend a lot of resources to mitigate the risk! For example, you should be interested in a more fancy monitoring that is 60% likely to catch the AI instead of just 30%, despite the fact that the net-sabotage-value of the persuasion attempt is negative in both cases.

Final note: don’t use this argument for wildly superintelligent AIs

While this argument technically also applies to wildly superintelligent schemers, it likely has very little practical implications for those AIs: