Why Have Sentence Lengths Decreased?

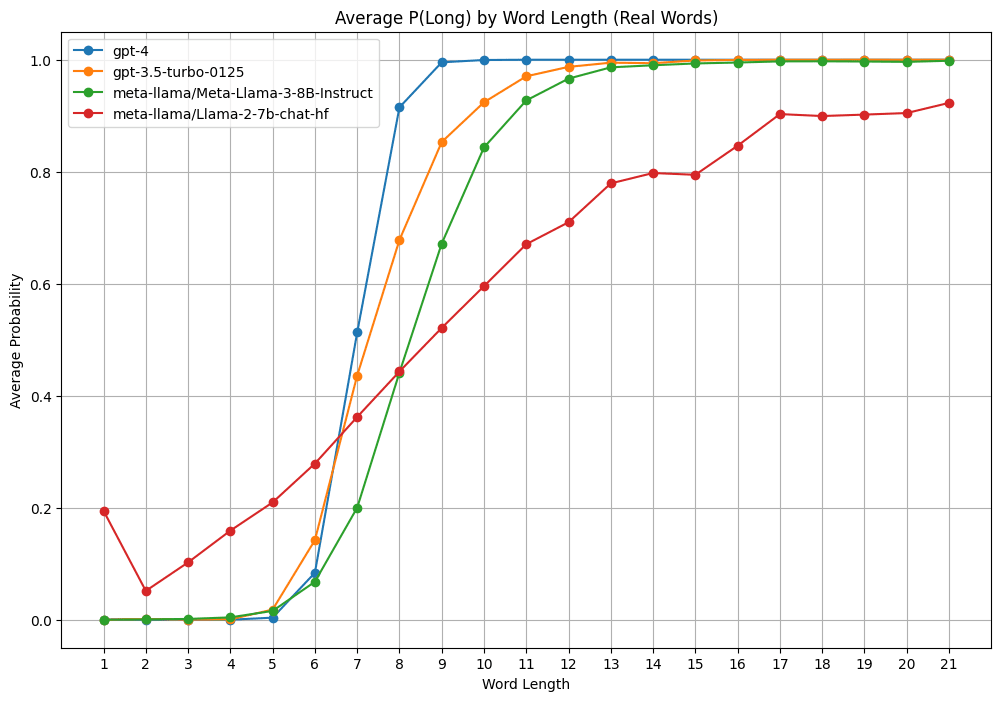

> “In the loveliest town of all, where the houses were white and high and the elms trees were green and higher than the houses, where the front yards were wide and pleasant and the back yards were bushy and worth finding out about, where the streets sloped down to the stream and the stream flowed quietly under the bridge, where the lawns ended in orchards and the orchards ended in fields and the fields ended in pastures and the pastures climbed the hill and disappeared over the top toward the wonderful wide sky, in this loveliest of all towns Stuart stopped to get a drink of sarsaparilla.” > — 107-word sentence from Stuart Little (1945) Sentence lengths have declined. The average sentence length was 49 for Chaucer (died 1400), 50 for Spenser (died 1599), 42 for Austen (died 1817), 20 for Dickens (died 1870), 21 for Emerson (died 1882), 14 for D.H. Lawrence (died 1930), and 18 for Steinbeck (died 1968). J.K Rowling averaged 12 words per sentence (wps) writing the Harry Potter books 25 years ago. So the decline predates television, the radio, and the telegraph—it’s been going on for centuries. The average sentence length in newspapers fell from 35wps to 20wps between 1700 and 2000. The presidential State of the Union address has gone from 40wps down to under 20wps, and the inaugural addresses had a similar decline. (From Jefferson through T. Roosevelt, the SOTU address was delivered to Congress without any speech, and print was the main way that inaugural addresses were consumed for most of their history.) Warren Buffett’s annual letter to shareholders dropped from 17.4wps to 13.4wps between 1974 and 2013. SlateStarCodex’s ten recommended blog posts have 22wps. My own top 10 posts have 20wps. Even top medical journals have under 25wps. The FAA, the European Commission, and various legal institutions have style guides recommending to stay under 20wps. Skimming r/writing, it looks like people recommend 10-15wps for fiction (HPMOR has 15wps). It’s possible that senten

Yes, that's a typo.

This is too historically contingent. Presidential systems have dominated the less stable American and African countries while European and Asian countries that have been more stable more often have parliaments. I'm not convinced that there is empirical evidence of this kind.

I agree that parliaments have a much more intuitive nature. Corporations are run with a sovereign board who appoints a dictatorial CEO, not with independent branches of power in a balance.

Why do you think it's better to have term limits?