It's useful for evals to be run reliably for every model and maintained for long periods. A lot of the point of safety-relevant evals is to be a building block people can use for other things: they can make forecasts/bets about what models will score on the eval or what will happen if a certain score is reached, they can make commitments about what to do if a model achieves a certain score, they can make legislation that applies only to models with specific scores, and they can advise the world to look to these scores to understand if risk is high.

Much of that falls apart if there's FUD about whether a given eval will still exist and be run on the relevant models in a year's time.

This didn't used to be an issue because evals used to be simple to run; they were just a simple script asking a model a series of multiple-choice questions.

Agentic evals are complex. They require GPUs and containers and scripts that need to be maintained. You need to scaffold your agent and run it for days. Sometimes you need to build a vending machine.

I'm worried about a pattern where a shiny new eval is developed, run for a few months, then discarded in favor of newer, better evals. Or where the folks running the evals don't get around to running them reliably for every model.

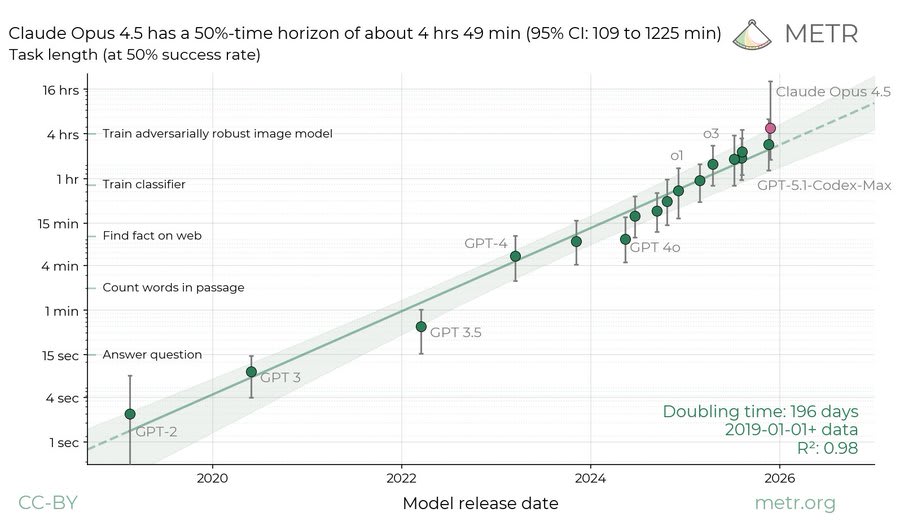

As a concrete example, the 2025 AI Forecasting Survey asked people to forecast what the best model's score on RE-Bench would be by the end of 2025, but RE-Bench hasn't been run on Claude Opus 4.5, or on many other recent models (METR focuses on their newer, larger time-horizon eval instead). It also asked for forecasted scores on OS-World, but OS-World isn't run anymore (it's been replaced by OSWorld-Verified).

There are real costs to running these evals, and when they're deprecated, it's usually because they're replaced with something better. But I think sometimes people act like this is a completely costless action and I want to point out the costs.

Some of that error is correlated between models; they also have versions of the graph with error bars on the trendline and those error bars are notably smaller.

The error bars are also much smaller when you look at the plot on a log-y-axis. Like, in some sense not being able to distinguish a 10-minute time horizon from a 30-minute one is a lot of error, but it's still very distinct from the one-minute time horizon of the previous generation or the 2-hour time horizon you might expect from the next generation. In other words, when you look at the image you shared, the error bars on o4 mini don't look so bad, but if you were only looking at models up to o4 mini you'd have zoomed in a bunch and the error bars on o4 mini would be large too.

Also note that to cut the size of the error bars in half you'd need to make ~4x as many tasks, to cut it by 4x you'd need ~16x as many tasks. And you'd need to be very confident the tasks weren't buggy, so just throwing money at the wall and hiring lots of people won't work because you'll just get a bunch of tasks you won't have confidence in.

Keep in mind the opportunity cost is real though, and the main blocker on orgs like METR usually is more like talent/capacity than money. It would be great if they had capacity for this and you're right that it is insane that humanity doesn't have better benchmarks. But there's a dozen other fires at least that large that METR seems to be trying to address, like RCTs to see if AI is actually speeding people up and risk report reviews to see if AIs are actually safe. Perhaps you think these are less important, but if so I would like to hear that argument.

All that said, my understanding is METR is working on this. I would also love to see this type of work from others!

I think that there are still very real trade-offs. Examples:

- Should you wear sunscreen?

- Should you smoke?

- Should you decrease sodium intake so that you don't develop hypertension?

And for many things wealth there is some short-term cost and some long-term longevity cost the long-term cost might be large enough to change the calculus.

Many people who think ASI will be developed soon seem to assume this means they should care less about their long-term health because in most worlds it won't matter: they figure most likely by the time they get old they'll either be dead or humanity will have cured aging and disease. I think it's important to remember that the bigger update is probably on the size of the value at stake, not the probability of health interventions mattering.

Even if ASI seems like it will happen soon, I think there's a real (if small) chance that humanity develops radical life-extension technology but not for another 50-100 years: maybe there's an AI winter, maybe medical research ends up being inherently slow (either for legal reasons or because it requires trials in humans, and those require the humans to actually age over time), maybe humanity decides to pause and not build ASI, maybe humanity decides to have a long reflection before building any crazy technology that cures death, etc.

The upside of hanging on to life until radical life-extension technology is developed seems extremely high: there are ten trillion years or so before the stars start to burn out (and you could probably live after the stars burn out, plus, you could run a simulation of yourself that lets you live a subjectively longer time). Even if you think there are steep diminishing returns to how long you live, getting to live into the depths of the far future probably gives you more control over how the future looks. If resources are divided equally amongst currently-living humans, you should eventually expect to get your own galaxy or two, but you'd need to live long enough for that space exploration and apportionment to be sorted out.[1] Even if that assumption is too rosy, every galaxy has a trillion or so planets. Probably someone will throw you one out of charity, and those odds go up if you live a long time.

The upside is so large that even though you might think the probability of this outcome is slim compared to worlds where humanity either goes extinct or quickly cures aging and disease, it still seems overwhelmingly important to shoot for.[2]

If you buy this worldview, you probably want to focus on preserving your mind: avoiding risk factors for dementia/strokes, avoiding concussions/head trauma, avoiding literally dying.

- ^

Maybe you could try to wield similar influence through a will, but this means (1) you don't get to experience the benefits firsthand, (2) the will might not specify what you want well enough, (3) you might not get as many resources; people don't tend to pay as much heed to the wishes of dead people.

- ^

Unless it's trading off with other goals on a similar scale, such as if you are an altruist trying to make the future better.

When I was first trying to learn ML for AI safety research, people told me to learn linear algebra. And today lots of people I talk to who are trying to learn ML[1] seem under the impression they need to master linear algebra before they start fiddling with transformers. I find in practice I almost never use 90% of the linear algebra I've learned. I use other kinds of math much more, and overall being good at empiricism and implementation seems more valuable than knowing most math beyond the level of AP calculus.

The one part of linear algebra you do absolutely need is a really, really good intuition for what a dot product is, the fact that you can do them in batches, and the fact that matrix multiplication is associative. Someone smart who can't so much as multiply matrices can learn the basics in an hour or two with a good tutor (I've taken people through it in that amount of time). The introductory linear algebra courses I've seen[2] wouldn't drill this intuition nearly as well as the tutor even if you took them.

In my experience it's not that useful to have good intuitions for things like eigenvectors/eigenvalues or determinants (unless you're doing something like SLT). Understanding bases and change-of-basis is somewhat useful for improving your intuitions, and especially useful for some kinds of interp, I guess? Matrix decompositions are useful if you want to improve cuBLAS. Sparsity sometimes comes up, especially in interp (it's also a very very simple concept).

The same goes for much of vector calculus. (You need to know you can take your derivatives in batches and that this means you write your d/dx as ∂/∂x or an upside-down triangle. You don't need curl or divergence.)

I find it's pretty easy to pick things like this up on the fly if you ever happen to need them.

Inasmuch as I do use math, I find I most often use basic statistics (so I can understand my empirical results!), basic probability theory (variance, expectations, estimators), having good intuitions for high-dimensional probability (which is the only part of math that seems underrated for ML), basic calculus (the chain rule), basic information theory ("what is KL-divergence?"), arithmetic, a bunch of random tidbits like "the log derivative trick", and the ability to look at equations with lots of symbols and digest them.

In general most work and innovation[3] in machine learning these days (and in many domains of AI safety[4]) is not based in formal mathematical theory, it's based on empiricism, fussing with lots of GPUs, and stacking small optimizations. As such, being good at math doesn't seem that useful for doing most ML research. There are notable exceptions: some people do theory-based research. But outside these niches, being good at implementation and empiricism seems much more important; inasmuch as math gives you better intuitions in ML, I think reading more empirical papers or running more experiments or just talking to different models will give you far better intuitions per hour.

- ^

By "ML" I mean things involving modern foundation models, especially transformer-based LLMs.

- ^

It's pretty plausible to me that I've only been exposed to particularly mediocre math courses. My sample-size is small, and it seems like course quality and content varies a lot.

- ^

Please don't do capabilities mindlessly.

- ^

The standard counterargument here is these parts of AI safety are ignoring what's actually hard about ML and that empiricism won't work. For example we need to develop techniques that work on the first model we build that can self-improve. I don't want to get into that debate.

The other day I was speaking to one of the most productive people I’d ever met.[1] He was one of the top people in a very competitive field who was currently single-handedly performing the work of a team of brilliant programmers. He needed to find a spot to do some work, so I offered to help him find a desk with a monitor. But he said he generally liked working from his laptop on a couch, and he felt he was “only 10% slower” without a monitor anyway.

I was aghast. I’d been trying to optimize my productivity for years. A 10% productivity boost was a lot! Those things compound! How was this man, one of the most productive people I’d ever met, shrugging it off like it was nothing?

I think this nonchalant attitude towards productivity is fairly common in top researchers (though perhaps less so in top executives?). I have no idea why some people are so much more productive than others. It surprises me that so much variance is even possible.

This guy was smart, but I know plenty of people as smart as him who are far less productive. He was hardworking, but not insanely so. He wasn’t aggressively optimizing his productivity.[2] He wasn't that old so it couldn't just be experience. Probably part of it was luck, but he had enough different claims to fame that that couldn’t be the whole picture.

If I had to chalk it up to something, I guess I'd call it skill and “research taste”: he had a great ability to identify promising research directions and follow them (and he could just execute end-to-end on his ideas without getting lost or daunted, but I know how to train that).

I want to learn this skill, but I have no idea how to do it and I'm still not totally sure it's real. Conducting research obviously helps, but that takes time and is clearly not sufficient. Maybe I should talk to a bunch of researchers and try to predict the results of their work?

Has anyone reading this ever successfully cultivated an uncanny ability to identify great research directions? How did you do it? What sub-skills does it require?

Am I missing some other secret sauce that lets some people produce wildly more valuable research than others?

- ^

Measured by more conventional means, not by positive impact on the long-term future; that's dominated by other people. Making sure your work truly steers at solving the world's biggest problems still seems like the best way to increase the value you produce, if you're into that sort of thing. But I think this person's abilities would multiply/complement any benefits from steering towards the most impactful problems.

- ^

Or maybe he was but there are so many 2x boosts the 10% ones aren’t worth worrying about?

Fair enough. This doesn't seem central to my point so I don't really want to go down a rabbit-hole here. As I said originally "I’m picking this example not because it’s the best analysis of its kind, but because it’s the sort of analysis I think people should be doing all the time and should be practiced at, and I think it's very reasonable to produce things of this quality fairly regularly." I know this particular analysis surfaced some useful considerations others' hadn't thought of, and I learned things from reading it.

I also suspect you dislike the original analysis for reasons that stem from deep-seated worldview disagreements with Eric, not because the methodology is flawed.

The advice and techniques from the rationality community seem to work well at avoiding a specific type of high-level mistake: they help you notice weird ideas that might otherwise get dismissed and take them seriously. Things like AI being on a trajectory to automate all intellectual labor and perhaps take over the world, animal suffering, longevity, cryonics. The list goes on.

This is a very valuable skill and causes people to do things like pivot their careers to areas that are ten times better. But once you’ve had your ~3-5 revelations, I think the value of these techniques can diminish a lot.[1]

Yet a lot of the rationality community’s techniques and culture seem oriented around this one idea, even on small scales: people pride themselves on being relentlessly truth-seeking and willing to consider possibilities they flinch away from.

On the margin, I think the rationality community should put more empasis on skills like:

Performing simple cost-effectiveness estimates accurately

I think very few people in the community could put together an analysis like this one from Eric Neyman on the value of a particular donation opportunity (see the section “Comparison to non-AI safety opportunities”). I’m picking this example not because it’s the best analysis of its kind, but because it’s the sort of analysis I think people should be doing all the time and should be practiced at, and I think it's very reasonable to produce things of this quality fairly regularly.

When people do practice this kind of analysis, I notice they focus on Fermi estimates where they get good at making extremely simple models and memorizing various numbers. (My friend’s Anki deck includes things like the density of typical continental crust, the dimensions of a city block next to his office, the glide ratio of a hang glider, the amount of time since the last glacial maximum, and the fraction of babies in the US that are twins).

I think being able to produce specific models over the course of a few hours (where you can look up the glide ratio of a hang glider if you need it) is more neglected but very useful (when it really counts, you can toss the back of the napkin and use a whiteboard).

Simply noticing something might be a big deal is only the first step! You need to decide if it’s worth taking action (how big a deal is it exactly?) and what action to take (what are the costs and benefits of each option?). Sometimes it’s obvious, but often it isn’t, and these analyses are the best way I know of to improve at this, other than “have good judgement magically” or “gain life experience”.

Articulating all the assumptions underlying an argument

A lot of the reasoning I see on LessWrong feels “hand-wavy”: it makes many assumptions that it doesn’t spell out. That kind of reasoning can be valuable: often good arguments start as hazy intuitions. Plus many good ideas are never written up at all and I don’t want to make the standards impenetrably high. But I wish people recognized this shortcoming and tried to remedy it more often.

By "articulating assumptions” I mean outlining the core dynamics at play that seem important, the ways you think these dynamics work, and the many other complexities you’re ignoring in your simple model. I don’t mean trying to compress a bunch of Bayesian beliefs into propositional logic.

Contact with reality

It’s really really powerful to look at things directly (read data, talk to users, etc), design and run experiments, and do things in the world to gain experience.

Everyone already knows this, empiricism is literally a virtue of rationality. But I don’t see people employing it as much as they should be. If you’re worried about AI risk, talk to the models! Read raw transcripts!

Scholarship

Another virtue of rationality. It's in the sequences, just not as present in the culture as you might expect. Almost nobody I know reads enough. I started a journal club at my company and after nearly every meeting folks tells me how useful it is. I so often see so much work that would be much better if the authors engaged with the literature a little more. Of course YMMV depending on the field you’re in; some literature isn't worth engaging with.

Being overall skilled and knowledgeable and able to execute on things in the real world

Maybe this doesn’t count as a rationality skill per-se, but I think the meta skill of sitting down and learning stuff and getting good at it is important. In practice the average person reading this short form would probably be more effective if they spent their energy developing whatever specific concrete skills and knowledge were most blocking them.

This list is far from complete.[2] I just wanted to gesture at the general dynamic.

- ^

They’re still useful. I could rattle off a half-dozen times this mindset let me notice something the people around me were missing and spring into action.

- ^

I especially think there's some skill that separates people with great research taste from people with poor research taste that might be crucial, but I don't really know what it is well enough to capture it here.

Sorry this is what I meant, you're right.

Yep I had Eliezer and Nate Soares in mind when I wrote the footnote "Some people don't think nonhuman animals are sentient beings, but I feel relatively confident they're applying a standard Peter Singer would approve of as morally consistent."

Note that Eliezer has written a relatively thoughtful justification on his vies of theory of mind and why he thinks various farmed animals aren't moral patients. He also says:

I disagree with Eliezer, but I think he's thinking far more carefully about animal welfare than the vast majority of the population.

I think the majority of (the very modest amount of) progress in thinking on this topic has come more from AI safety folks than animal welfare folks. Can you link me good writing on this quetion from animal welfare folks?