Trained neural networks only generalize at all with certain types of activation functions. So if your theory doesn't consider activation functions it's probably wrong.

If a model is singular, then Watanabe’s Free Energy Formula (FEF) can have big implications for the geometry of the loss landscape. Whether or not a particular neural network model is singular does indeed depend on its activation function, amongst other structures in its architecture.

In DSLT3 I will outline the ways simple two layer feedforward ReLU neural networks are singular models (ie I will show the symmetries in parameter space that produce the same input-output function), which is generalisable to deeper feedforward ReLU networks. There I will also discuss similar results for tanh networks, alluding to the fact that there are many (but not all) activation functions that produce these symmetries, thus making neural networks with those activation functions singular models, thus meaning the content and interpretation of Watanabe’s free energy formula is applicable.

This is all pretty complicated compared to my understanding of why neural networks generalize, and I'm not sure why I should prefer it. Does this complex and detailed theory have any concrete predictions about NN design or performance in different circumstances? Can you accurately predict which activation functions work well?

My view is that this "singularity" of networks - which I don't think is a good term, it's already overloaded with far too many meanings - is applicable to convergence properties but not to generalization ability.

What is your understanding? It is indeed a deep mathematical theory, but it is not convoluted. Watanabe proves the FEF, and shows the RLCT is the natural generalisation of complexity in this setting. There is a long history of deep/complicated mathematics, with natural (and beautiful) theorems at the core, being pivotal to describing real world phenomena.

The point of the posts is not to argue that we can prove why particular architectures perform better than others (yet). This field has had, comparatively, very little work done to it yet within AI research, and these sorts of facts are where SLT might take us (modulo AI capabilities concerns). The point is to demonstrate the key insights of the theory and signpost the fact that “hey, there might be something very meaningful here.” What we can predict with the theory is why certain phase transitions happen, in particular the two layer feedforward ReLU nets I will show in DSLT4. This is a seed from which to generalise to deeper nets and more intricate architectures - the natural way of doing good mathematics.

As to the “singularity” problem, you will have to take that up with the algebraic geometers who have been studying singularities for over 50 years. The fact is that optimal parameters are singularities of K(w) in non-trivial neural networks - hence, singular learning theory.

What do “convergence properties” and “generalisation ability“ mean to you, precisely? It is an indisputable fact that Watanabe proves (and I elaborate on in the post) that this singularity structure plays a central role in Bayesian generalisation. As I say, its relation to SGD dynamics is certainly an open question. But in the Bayesian setting, the case is really quite closed.

What is your understanding?

I guess I'll write a post.

It is an indisputable fact that Watanabe proves (and I elaborate on in the post) that this singularity structure plays a central role in Bayesian generalisation

No. What was proven is that there are some points which can be represented by lots of possible configurations, more so than other points. There is no proof or even evidence that those are reached by NN training by SGD, or that those points represent good solutions to problems. As far as I can tell, you're just assuming that because it seems to you like a logical reason for NN generalization.

With all due respect, I think you are misrepresenting what I am saying here. The sentence after your quote ends is

its relation to SGD dynamics is certainly an open question.

What is proven by Watanabe is that the Bayesian generalisation error, as I described in detail in the post, strongly depends on the singularity structure of the minima of , as measured by the RLCT . This fact is proven in [Wat13] and explained in more detail in [Wat18]. As I elaborate on in the post, translating this statement into the SGD / frequentist setting is an interesting and important open problem, if it can be done at all.

I said I'd write a post, and I wrote a post.

the Bayes generalisation error Gn is the "derivative" of the free energy

I think calling that "Bayes generalisation error" is where you went wrong. I see no good basis for saying that's true in the sense people normally mean "generalization".

I understand some things about a Free Energy Formula are proved, but I don't think you've shown anything about low RLCT points tending to be the sort of useful solutions which neural networks find.

Thanks for writing that, I look forward to reading.

As for nomenclature, I did not define it - the sequence is called Distilling SLT, and this is the definition offered by Watanabe. But to add some weight to it, the point is that in the Bayesian setting, the predictive distribution is a reasonable object to study from the point of view of generalisation, because it says: "what is the probability of this output given this input and given the data of the posterior". The Bayes training loss (which I haven't delved into in this post) is the empirical counterpart to the Bayes generalisation loss,

and so it adds up the "entropy" of the predictive distribution over the training datapoints - if the predictive distribution is certain about all training datapoints, then the training loss will be 0. (Admittedly, this is an object that I am still getting my head around).

The Bayes generalisation loss satisfies , and therefore it averages this training loss over the whole space of inputs and outputs. This is the sense in which it is reasonable to call it "generalisation". As I say in the post, there are other ways you can think of generalisation in the Bayesian setting, like the leave-one-out-cross-validation, or other methods of extracting data from the posterior like Gibbs sampling. Watanabe shows (see pg236 of [Wat18]) that the RLCT is a central object in all of these alternative conceptions.

As for the last point, neural networks do not "find" anything themselves - either an optimisation method like SGD does, or the Bayesian posterior "finds" regions of high posterior concentration (i.e. it contains this information). SLT tells us that the Bayesian posterior of singular models does "find" low RLCT points (as long as they are sufficiently accurate). Neural networks are singular models (as I will explain in DSLT3), so the posterior of neural networks "finds" low RLCT points.

Does this mean SGD does? We don't know yet! And whether your intuition says this is a fruitful line of research to investigate is completely personal to your own mental model of the world, I suppose.

Thanks for this nice post! I fight it slightly more vague than the first post, but I guess that is hard to avoid when trying to distill highly technical topics. I got a lot out of it.

Fundamentally, we care about the free energy because it is a measure of posterior concentration, and as we showed with the BIC calculation in DSLT1, it tells us something about the information geometry of the posterior.

Can you tell more about why it is a measure of posterior concentration (It gets a bit clearer further below, but I state my question nonetheless to express that this statement isn't locally clear to me here)? I may lack some background in Bayesian statistics here. In the first post, you wrote the posterior as

and it seems like you want to say that if free energy is low, then the posterior is more concentrated. If I look at this formula, then low free energy corresponds to high , meaning the prior and likelihood have to "work quite a bit" to ensure that this expression overall integrates to . Are you claiming that most of that work happens very localized in a small parameter region?

Additionally, I am not quite sure what you mean with "it tells us something about the information geometry of the posterior", or even what you mean by "information geometry" here. I guess one answer is that you showed in post 1 that the Fisher information matrix appears in the formula for the free energy, which contains geometric information about the loss landscape. But then in the proof, you regarded that as a constant that you ignored in the final BIC formula, so I'm not sure if that's what you are referring to here. More explicit references would be useful to me.

Since there is a correspondence

we say the posterior prefers a region when it has low free energy relative to other regions of .

Note to other readers (as this wasn't clear to me immediately): That correspondence holds because one can show that

Here, is the global partition function.

The Bayes generalisation loss is then given by

I believe the first expression should be an expectation over .

It follows immediately that the generalisation loss of a region is

I didn't find a definition of the left expression.

So, the region in that minimises the free energy has the best accuracy-complexity tradeoff. This is the sense in which singular models obey Occam's Razor: if two regions are equally accurate, then they are preferred according to which is the simpler model.

Purposefully naive question: can I just choose a region that contains all singularities? Then it surely wins, but this doesn't help us because this region can be very large.

So I guess you also want to choose small regions. You hinted at that already by saying that should be compact. But now I of course wonder if sometimes just all of lies within a compact set.

There are two singularities in the set of true parameters,

which we will label as and respectively.

Possible correction: one of those points isn't a singularity, but a regular loss-minimizing point (as you also clarify further below).

Let's consider a one parameter model with KL divergence defined by

on the region with uniform prior

The prior seems to do some work here: if it doesn't properly support the region with low RLCT, then the posterior cannot converge there. I guess a similar story might a priori hold for SGD, where how you initialize your neural network might matter for convergence.

How do you think about this? What are sensible choices of priors (or network initializations) from the SLT perspective?

Also, I find it curious that in the second example, the posterior will converge to the lowest loss, but SGD would not since it wouldn't "manage to get out of the right valley", I assume. This seems to suggest that the Bayesian view of SGD can at most be true in high dimensions, but not for very low-dimensional neural networks. Would you agree with that, or what is your perspective?

Can you tell more about why it is a measure of posterior concentration.

...

Are you claiming that most of that work happens very localized in a small parameter region?

Given a small neighbourhood , the free energy is and measures the posterior concentration in since

where the inner term is the posterior, modulo its normalisation constant . The key here is that if we are comparing different regions of parameter space , then the free energy doesn't care about that normalisation constant as it is just a shift in by a constant. So the free energy gives you a tool for comparing different regions of the posterior. (To make this comparison rigorous, I suppose one would want to make sure that these regions are the same "size". Another perspective, and really the main SLT perspective, is that if they are sufficiently small and localised around different singularities then this size problem isn't really relevant, and the free energy is telling you something about the structure of the singularity and the local geometry of around the singularity).

I am not quite sure what you mean with "it tells us something about the information geometry of the posterior"

This is sloppily written by me, apologies. I merely mean to say "the free energy tells us what models the posterior likes".

I didn't find a definition of the left expression.

I mean, the relation between and tells you that this is a sensible thing to write down, and if you reconstructed the left side from the right side you would simply find some definition in terms of the predictive distribution restricted to (instead of in the integral).

Purposefully naive question: can I just choose a region that contains all singularities? Then it surely wins, but this doesn't help us because this region can be very large.

Yes - and as you say, this would be very uninteresting (and in general you wouldn't know what to pick necessarily [although we did in the phase transition DSLT4 because of the classification of in DSLT3]). The point is that at no point are you just magically "choosing" a anyway. If you really want to calculate the free energy of some model setup then you would have a reason to choose different phases to analyse. Otherwise, the premise of this section of the post is to show that the geometry depends on the singularity structure and this varies across parameter space.

Possible correction: one of those points isn't a singularity, but a regular loss-minimizing point (as you also clarify further below).

As discussed in the comment in your DSLT1 question, they are both singularities of since they are both critical points (local minima). But they are not both true parameters, nor are they both regular points with RLCT .

How do you think about this? What are sensible choices of priors (or network initializations) from the SLT perspective?

I think sensible choices of priors has an interesting and not-interesting angle to it. The interesting answer might involve something along the lines of reformulating the Jeffreys prior, as well as noticing that a Gaussian prior gives you a "regularisation" term (and can be thought of as adding the "simple harmonic oscillator" part to the story). The uninteresting answer is that SLT doesn't care about the prior (other than its regularity conditions) since it is irrelevant in the limit. Also if you were concerned with the requirement for to be compact, you can just define it to be compact on the space of "numbers that my computer can deal with".

Also, I find it curious that in the second example, the posterior will converge to the lowest loss, but SGD would not since it wouldn't "manage to get out of the right valley", I assume. This seems to suggest that the Bayesian view of SGD can at most be true in high dimensions, but not for very low-dimensional neural networks. Would you agree with that, or what is your perspective?

Yes! We are thinking very much about this at the moment and I think this is the correct intuition to have. If one runs SGD on the potential wells , you find that it just gets stuck in the basin it was closest to. So, what's going on in high dimensions? It seems something about the way higher dimensional spaces are different from lower ones is relevant here, but it's very much an open problem.

Thanks for the answer! I think my first question was confused because I didn't realize you were talking about local free energies instead of the global one :)

As discussed in the comment in your DSLT1 question, they are both singularities of since they are both critical points (local minima).

Oh, I actually may have missed that aspect of your answer back then. I'm confused by that: in algebraic geometry, the zero's of a set of polynomials are not necessarily already singularities. E.g., in , the zero set consists of the two axes, which form an algebraic variety, but only at is there a singularity because the derivative disappears.

Now, for the KL-divergence, the situation seems more extreme: The zero's are also, at the same time, the minima of , and thus, the derivative disappears at every point in the set . This suggests every point in is singular. Is this correct?

So far, I thought "being singular" means the effective number of parameters around the singularity is lower than the full number of parameters. Also, I thought that it's about the rank of the Hessian, not the vanishing of the derivative. Both perspectives contradict the interpretation in the preceding paragraph, which leaves me confused.

The uninteresting answer is that SLT doesn't care about the prior (other than its regularity conditions) since it is irrelevant in the limit.

I vaguely remember that there is a part in the MDL book by Grünwald where he explains how using a good prior such as Jeffrey's prior somewhat changes asymptotic behavior for , but I'm not certain of that.

Now, for the KL-divergence, the situation seems more extreme: The zero's are also, at the same time, the minima of , and thus, the derivative disappears at every point in the set . This suggests every point in is singular. Is this correct?

Correct! So, the point is that things get interesting when is more than just a single point (which is the regular case). In essence, singularities are local minima of . In the non-realisable case this means they are zeroes of the minimum-loss level set. In fact we can abuse notation a bit and really just refer to any local minima of as a singularity. The TLDR of this is:

So far, I thought "being singular" means the effective number of parameters around the singularity is lower than the full number of parameters. Also, I thought that it's about the rank of the Hessian, not the vanishing of the derivative. Both perspectives contradict the interpretation in the preceding paragraph, which leaves me confused.

As I show in the examples in DSLT1, having degenerate Fisher information (i.e. degenerate Hessian at zeroes) comes in two essential flavours: having rank-deficiency, and having vanishing second-derivative (i.e. ). Precisely, suppose is the number of parameters, then you are in the regular case if can be expressed as a full-rank quadratic form near each singularity,

Anything less than this is a strictly singular case.

I vaguely remember that there is a part in the MDL book by Grünwald where he explains how using a good prior such as Jeffrey's prior somewhat changes asymptotic behavior for , but I'm not certain of that.

Watanabe has an interesting little section in the grey book [Remark 7.4, Theorem 7.4, Wat09] talking about the Jeffrey's prior. I haven't studied it in detail but to the best of my reading he is basically saying "from the point of view of SLT, the Jeffrey's prior is zero at singularities anyway, its coordinate-free nature makes it inappropriate for statistical learning, and the RLCT can only be if the Jeffrey's prior is employed." (The last statement is the content of the theorem where he studies the poles of the zeta function when the Jeffrey's prior is employed).

Thanks for the reply!

As I show in the examples in DSLT1, having degenerate Fisher information (i.e. degenerate Hessian at zeroes) comes in two essential flavours: having rank-deficiency, and having vanishing second-derivative (i.e. ). Precisely, suppose is the number of parameters, then you are in the regular case if can be expressed as a full-rank quadratic form near each singularity,

Anything less than this is a strictly singular case.

So if , then is a singularity but not a strict singularity, do you agree? It still feels like somewhat bad terminology to me, but maybe it's justified from the algebraic-geometry--perspective.

If contains one true parameter ,

Having trouble parsing this. Does this mean that one element of the parameter vector is “true”?

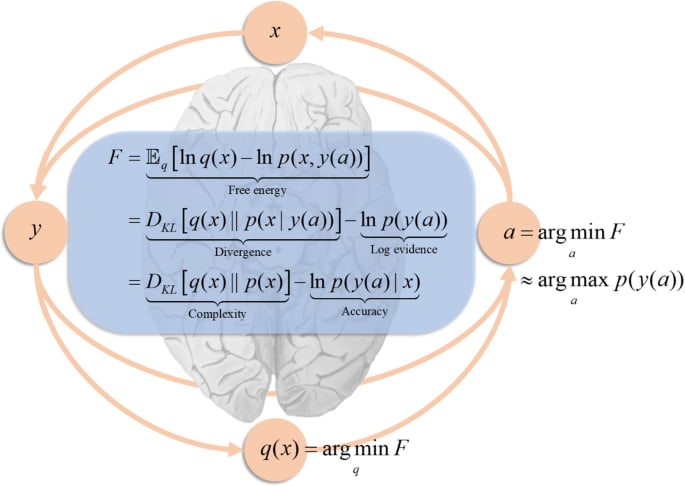

TLDR; This is the second main post of Distilling Singular Learning Theory which is introduced in DSLT0. I synthesise why Watanabe's free energy formula explains why neural networks have the capacity to generalise well, since different regions of the loss landscape have different accuracy-complexity tradeoffs. I also provide some simple intuitive examples that visually demonstrate why true parameters (i.e. optimally accurate parameters) are preferred according to the RLCT as n→∞, and why non-true parameters can still be preferred at finite n if they have lower RLCT's, due to the accuracy-complexity tradeoff. (The RLCT is introduced and explained in DSLT1).

It is an amazing fact that deep neural networks seem to have an inductive bias towards "simple" models, suggesting that they obey a kind of Occam's Razor:

or in modern parlance,

This allows them to achieve exceptionally low generalisation error despite classical statistics predictions that they should overfit data:

(Source: OpenAI's Double Descent blogpost).

This fact has come to be known as the generalisation problem and has been discussed at length in Zhang et. al 2017 (and a 2021 supplement), and in Bengio et al., amongst countless others.

Remarkably, Singular Learning Theory can help explain why neural networks, which are singular models, have the capacity to generalise so well.

The degeneracy of the Fisher information matrix is actually a feature of singular models, not a bug. This is because different regions of parameter space can have different complexities as measured by the RLCT λ, unlike regular models where the complexity is fixed to the total number of parameters in the model d. This is the implicit content of Watanabe's profound free energy formula, called the Widely Applicable Bayesian Information Criterion (WBIC), which quantifies a precise asymptotic tradeoff between inaccuracy and complexity,

WBIC=nLn(w(0))inaccuracy+λcomplexitylogn,giving a mathematically rigorous realisation of Occam's Razor, since λ≤d2 in singular models.

In this post we will explore Watanabe's free energy formula and provide an intuitive example of why the RLCT matters so much. If you are new to statistical learning theory, I would recommend jumping straight to the examples and their related animations to gain the intuition first, and then return to the theory afterwards.

The four key points to take away are:

- As n→∞, true parameters with the best accuracy will always be preferred.

- As n→∞, if two true parameters are equally accurate but have different RLCT's, the parameter with the lower RLCT is preferred.

- For finite but large n, non-true parameters can be preferred by the posterior because of an accuracy-complexity tradeoff as measured by the WBIC.

- Parameters with low inaccuracy and small RLCT's λ have low generalisation error (in a Bayesian sense) since the Bayes generalisation error Gn is the "derivative" of the free energy, so

Gn=Ln(w(0))+λn+o(1n).Information Criteria Help Avoid Underfitting and Overfitting

In the last post, we derived the asymptotic free energy Fn as n→∞ for regular models, called the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC):

BIC=nLn(w(0))+d2logn,where n is the total number of datapoints in the dataset Dn, the optimal loss is Ln(w(0)) where w(0)∈W is a maximum likelihood estimate (i.e. w(0)=argminW(L(w))), and d is the total dimension of parameter space W⊆Rd.

As a statistical practitioner, given some dataset Dn, your goal is to find a model that you hope will represent the truth from some candidate list. You only have access to the truth via your (training) dataset Dn, but you also want to ensure that it generalises to data beyond the dataset. You can use the BIC to compare model candidates across a set of model classes that you can think to compare, since it captures a precise asymptotic tradeoff between inaccuracy Ln(w(0)) and complexity d2. Under this paradigm, we should choose the model that achieves the lowest BIC as it is the best option for avoiding both underfitting and overfitting the data. Let's consider a simple example in action:

Example 1: Suppose we have n=61 datapoints drawn from a quadratic with Gaussian noise, y=x2+ε where ε∼N(0,0.152)[1], where x is drawn according to a uniform prior q(x)=121(x∈[−1,1]). After looking at our scatterplot of data Dn, we could try models across the following set of model classes:

(The degree 15 model is an extremity just to illustrate a point.)

Within each model class, we can then perform ordinary least squares regression [2] to find the model fit w(0) with optimal loss Ln(w(0)) (which, in the regression case, is simply the mean-squared-error plus a constant[3]). With the optimal loss of each model class in hand, we can then compare the BIC over our set of candidates.

As one expects, in a similar vein to the bias-variance tradeoff, there is a clear optimal (lowest) BIC. As the dimension increases, the accuracy gets better and better, but at the cost of the complexity of the model (and therefore, its generalisability[4]). The linear model is simple, but has high loss. The cubic has marginally lower loss, but at the expense of a complexity increase that isn't worth it. The degree 15 polynomial has the lowest loss of them all, but is penalised heavily for its complexity (as it should be - it is clearly overfitting). The Goldilocks choice is unsurprisingly the quadratic model, f2(x), because the tradeoff between accuracy and complexity is just right.

Other than the fact that the BIC simply does not hold in the singular case, it also points us towards a limitation of regular models. Once you pick your model class to optimise, every point on the loss landscape has a fixed model complexity. If your goal is to minimise the BIC, you only have one choice: to find the single point that optimises the loss at the bottom of the well.

In fact, in our particular case, we can calculate the KL divergence [5] for the linear model f2(x,w),

K(w0,w1)=16w21+12(w0−13)2+245,which we can see a plot of below.

In singular models, this all changes: within the same model class, different models w in parameter space W have different effective dimensionalities as measured by the RLCT λ. The learning procedure does the work of the statistician for us, because the loss landscape contains information about both the accuracy and the complexity.

Watanabe's Free Energy Formula for Singular Models

Free Energy, Generalisation and Model Selection

Fundamentally, we care about the free energy Fn=−logZn because it is a measure of posterior concentration, and as we showed with the BIC calculation in DSLT1, it tells us something about the information geometry of the posterior. In particular, given a compact neighbourhood of parameter space W⊆W we can define its local free energy

Fn(W)=−log(∫Wφ(w)e−nLn(w)dw),providing a direct tool for comparing different regions of the posterior, and thus different models. Since there is a correspondence

SmallFn(W)⟺Large posterior concentration∫Wp(w|Dn)dw,we say the posterior prefers a region W when it has low free energy relative to other regions of W.

But this isn't the only reason to care about the free energy. In fact, it is explicitly related to generalisation, at least in the Bayesian sense.

In the frequentist framework that real-world deep learning takes place in (i.e. estimating a single parameter ^w using SGD), we typically split our dataset Dn into a training set and a test set. We then say a model defined by ^w generalises well when it has low loss on the test set - in other words, it performs well on data that it hasn't seen before.

In the Bayesian paradigm, generalisation can be formulated according to a number of different estimation methods and quantities, depending on how you extract information from the posterior (e.g. you could estimate a maximum-likelihood parameter, a maximum a posterior estimate, or an average over samples from the posterior, etc.). Let's focus on one for the moment that involves the Bayes predictive distribution given by

p(y|x,Dn)=Ew[p(y|x,w)]=∫Wp(y|x,w)p(w|Dn)dw,which weights the probability of an output y given an input x according to the posterior measure. The Bayes generalisation loss is then given by

Gn=EX[−logp(y|x,Dn)]=−∬RN+Mq(y,x)logp(y|x,Dn)dxdy.Intuitively, it is the expected loss of the predictive distribution over all possible inputs x and outputs y. It can be shown with relative ease [6] that the Bayes generalisation loss is equal to the average increase in free energy,

Gn=EXn+1[Fn+1]−Fn.In an informal-yet-conceptually-correct way, we can treat this difference as being the "derivative with respect to n" [7].

It follows immediately that the generalisation loss of a region W⊆W is

Gn(W)=EXn+1[Fn+1(W)]−Fn(W).Ergo, to understand the information contained in the posterior, and which regions contain models with low generalisation error, we want to calculate the free energy. In even modestly simple settings this integral is intractable, thus why we need to calculate its asymptotic form.

The Free Energy Formula for Singular Models

This subsection is a little bit more technical. If this overwhelms you, I recommend skipping ahead to the next subsection where I interpret the free energy formula.

As I explained in DSLT1, finding the asymptotic form of the free energy Fn as n→∞ when I(w) is degenerate is hard, and depends of theorems of algebraic geometry and distribution theory. This formula has been refined over the course of many papers [8], adjusted and generalised with various hypotheses. Here we will focus on the form given in [Wat13], which also applies to the unrealisable case where the set of true parameters W0 may be empty. Thus we instead care about the set of optimal parameters

Wopt={w∈W|L(w)=minw′∈WL(w′)},and if W0 is non-empty, then W0=Wopt. As it stands, the free energy formula in the unrealisable case depends on a hypothesis of relatively finite variance [9].

Watanabe shows that the free energy of W asymptotically satisfies

Fn=nLn(w(0))+λlogn+Un√λlogn2+Op(1)asn→∞.where:

We will interpret the formula in a moment, but let me briefly clarify what it means to call w(0) a "most singular point", a notion is made precise in [Lin11, Proposition 3.9]. (See the below figure, too).

The gist is that every singularity w∈Wopt has an associated local RLCT λw defined by considering small neighbourhoods around the point. The global RLCT of W is defined to be the minimum over these optimal points, λ=minw∈Wopt{λw}, and an optimal point w(0)∈Wopt is a most singular point if λw(0)=λ [10]. Note also that the formula currently depends on an optimal parameter being in the interior of W, so you can think of a most singular point as being a local minimum of K(w).

The Widely Applicable Bayesian Information Criterion

In the asymptotic limit as n→∞, we can ignore the last two terms of the free energy formula and arrive at the Widely Applicable Bayesian Information Criterion (WBIC) across the full parameter space W,

WBIC=nLn(w(0))+λlogn.Notice how the WBIC formula is the same as the BIC except that complexity is measured by λ instead of d2. But in DSLT1, we explained how

Thus the WBIC is a generalisation of the BIC, containing the regular result as a special case.

Though the WBIC can be used to compare model classes like in the case of the BIC, its real power is what it tells us about the information geometry of the posterior within the same class of models. To this end, we can calculate the local free energy of a compact neighbourhood W⊆W

Fn(W)=nLn(w(0)W)+λWlogn,where w(0)W∈Wopt is the most singular optimal point in W with associated RLCT λW.

(Thanks to Jesse for the figure template).

The Accuracy-Complexity Tradeoff

The WBIC shows that the free energy of a region W⊆W is comprised of the accuracy and complexity (or, to the physicists, energy and entropy) of the most singular point in W

Fn(W)=nLn(w(0)W)inaccuracy+λWcomplexitylogn.What makes this so profound is that in singular models, different regions W⊂W can have different RLCT's λW, each with a different tradeoff between accuracy and complexity, unlike the regular model case where every region has a fixed complexity:

Regular models:Fn(W)=n(Inaccuracy(W))+logn(Constant Complexity)Singular models:Fn(W)=n(Inaccuracy(W))+logn(Complexity(W))So, the region in W that minimises the free energy has the best accuracy-complexity tradeoff. This is the sense in which singular models obey Occam's Razor: if two regions are equally accurate, then they are preferred according to which is the simpler model.

Interpreting the terms in the free energy formula leads us to three main points:

Why Singular Models (Can) Generalise Well

Armed with our free energy formula, we can now understand why singular models have the capacity to generalise well.

Recall that the Bayes generalisation error can be expressed as the difference Gn=EXn+1[Fn+1]−Fn, which can be interpreted as the "derivative" of the free energy with respect to n. Then since Fn=nLn(w(0))+λlogn, Watanabe is able to prove in [Wat18, Chapter 8] that, asymptotically, the Bayes generalisation error is

E[Gn]=L(w(0))+λn+o(1n).In fact, he goes one step further by considering two other forms of generalisation, the leave-one-out-cross-validation-loss CV, and the WAIC (an empirically measurable form of the WBIC), and shows that asymptotically

E[Gn]≈E[CV]≈E[WAIC]=L(w(0))+λn+o(1n).Once again, we find that the RLCT λ plays a central role in the learning process. Most importantly, we have a correspondence:

Optimal parameters w(0) with low RLCTλ⟺Low generalisation error.On top of this, we can carry out the same analysis on our local Fn(W) to find that the local generalisation loss of W is

E[Gn(W)]=L(w(0)W)+λWn.Since the RLCT can differ region to region, this tells us that:

In singular models, different regions W have different generalisation error.All of this is to say: under any reasonable conception of Bayesian generalisation, the RLCT plays a central role in minimising generalisation loss, asymptotically. And since λ≤d2 in singular models, the generalisation error of a singular model will always be better than that of a regular model with the same number of parameters. In DSLT3 we will show neural networks are singular, so:

This is why neural networks can generalise well!

...sort of. Don't forget, we are in the Bayesian paradigm here, and it is not a given that Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) finds the same regions of parameter space that the Bayesian posterior says are "good". We postulate that in some sense they are equivalent, and the work of Mingard et al. in Is SGD a Bayesian Sampler? Well, Almost. agrees with this postulate. But, formalising this relationship does remain a key open problem in conclusively applying SLT to modern deep learning with SGD and its variants.

From points to local neighbourhoods

For those with less background knowledge, there is an important conceptual shift we have made here that I want to elaborate on briefly.

In frequentist statistics we care about particular point estimates ^w in parameter space W. But in Bayesian statistics, we care about measurable regions W⊂W of parameter space, and the probability to which the posterior assigns those regions. This is a powerful shift in perspective, and points towards why SLT is placed in a Bayesian paradigm: the observation the geometry of K(w) contains a lot more information than simple point estimates do lends itself naturally to Bayesian statistics.

But in modern deep learning, we only ever have access to a point estimate ^w at the end of training via SGD. Sampling from the Bayesian posterior for large neural networks would not only be silly, but it would be, essentially, computationally impossible. So does this mean SLT has absolutely no applicability to modern deep learning?

Not at all. By studying the local geometry of the loss landscape K(w) - which is to say, arbitrarily small neighbourhoods W of the posterior - we are able to analyse the set of points that are arbitrarily close to the singularities of K(w).

What Watanabe shows is that the singularities contained in these small neighbourhoods affect the geometry of the other points in the neighbourhood. If W contains one true parameter w(0)∈W0, the other points in W may not be equal minima of K(w), but they are extremely close to being so. The same logic applies for the RLCT of a region: perhaps there is only one most singular point in W, but any nearby parameter within the small neighbourhood will define a model whose functional output is nearly identical to that of f(x,w(0)) which has a lower complexity.

In focusing only on points, we lose an extraordinary amount of information. So, we localise to neighbourhoods.

Intuitive Examples to Interpret the WBIC

It's time we looked at a specific example to build intuition about what the WBIC is telling us.

I have constructed this toy example specifically to illustrate the main points here, and a lot of the details about the sub-leading terms in the free energy expansion are obfuscated, as well as the random fluctuations that make Kn(w) different to K(w). But, it is conceptually correct, and helps to illustrate the dominant features of the learning process as n→∞. Don't take it too literally, but do take it seriously.

We will start with some calculations, and then visualise what this means for the posterior as n→∞.

Example 1: True parameters are preferred according to their RLCT

Let's consider a one parameter model d=1 with KL divergence defined by

K(w)=(w+1)2(w−1)4,on the region W=[−2,2] with uniform prior φ(w)=141(w∈W). There are two singularities in the set of true parameters,

W0={−1,1},which we will label as w(0)−1 and w(0)1 respectively. The Fisher information at true parameters is just the Hessian, which in the one dimensional case is simply the second derivative,

I(w(0))=J(w(0))=d2Kdw2∣∣w=w(0).An easy calculation shows

d2Kdw2=2(w−1)2(15w2+10w−1),meaning w(0)−1 is a regular point and w(0)1 is a singular point since

d2Kdw2∣∣w=−1=32,whereasd2Kdw2∣∣w=1=0,meaning the Fisher information "matrix" (albeit it is one-dimensional) is degenerate at w(0)1 but not at w(0)−1. We thus expect the RLCT of w(0)1 to be less than d2=12.

Let B(w0,δ)=[w0−δ,w0+δ]⊂W denote a small neighbourhood of radius δ>0 centred at w0. To analyse the geometry of K(w) near the two singularities, we can define compact local regions

W−1=B(w(0)−1,δ)andW1=B(w(0)1,δ).By taking a Taylor expansion about each singularity, the leading order terms of K(w) in each region are

W−1:K(w)≈16(w+1)2,and inW1:K(w)≈4(w−1)4,since δ is very small. Recalling the definition of the RLCT from DSLT1, since K(w) is in normal crossing form we can read off the local RLCTs

λ−1=12andλ1=14,meaning the effective dimensionalities associated to each singularity are 2λ−1=1 and 2λ1=12 respectively.

Here's the crux: since both singularities w(0)−1 and w(0)1 are true parameters, so K(w(0)−1)=K(w(0)1)=0, they both have the same accuracy S (a constant),

L(w(0)−1)=L(w(0)1)=S.But, since the RLCT associated to W1 is smaller, λ1<λ−1, the free energy formula tells us that W1 is preferred by the posterior since it has lower free energy,

Fn(W1)<Fn(W−1),and our generalisation formula tells us that W1 will have lower expected Bayesian generalisation loss,

Gn(W1)<Gn(W−1).The simpler model is preferred, and has a lower generalisation loss, because it has a lower RLCT.

Notice here how our δ was arbitrary. It doesn't matter exactly what it is, because as long as it is small, K(w) will look like 16(w+1)2 and 4(w−1)4 in each respective region. Its geometry is dominated by these terms when very close to each singularity.

K(w) is like a potential well, where a lower RLCT means a flatter floor

We argued in the first post that the RLCT is the correct measure of "flatness" in the loss landscape. We can now see that with our own eyes by plotting K(w) in our above example:

Looking at this plot, a good intuition to have is that the loss landscape K(w) is a potential well for some kinetic ball bouncing around, with its Hamiltonian given by H(w)≈nK(w). The ball, with enough random kinetic energy, will explore both regions W−1 and W1, but it will spend more time in the latter since it is "flatter" [11].

Animation 1: The posterior concentrates on both true parameters as n→∞, but it prefers the one with lower RLCT

For large n, the empirical KL divergence is approximately equal to the KL divergence Kn(w)≈K(w), and so normalising out by the constant S, the posterior effectively only depends on K(w):

p(w|Dn)≈φ(w)e−nK(w)∫2−2φ(w)e−nK(w)dw,which is shown with some easy algebraic manipulations [12].

The free energy formula predicts that W1 is preferred because λ1 is smaller than λ−1. So let's look at how the posterior changes with n:

As predicted, we visually see in the top posterior plot that the posterior concentration in W1 is greater than W−1 for all n. The bottom plot backs this up precisely by showing that the free energy Fn(W1) is always less than Fn(W−1). The RLCT clearly matters!

Note here that we have been able to numerically calculate the integrals Zn(W−1) and Zn(W1), indicated by the shaded regions precisely, and not based on the free energy formula. This is because numerical integration is easy in low dimensions. In even modest dimensionality, these partition functions are notoriously difficult to compute, thus giving rise to the field of computational Bayesian statistics and algorithms like Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Our neural network experiments in DSLT4 require the MCMC approach.

Example 2: Non-true parameters can be preferred at finite n because of the accuracy-complexity tradeoff

Let's alter our example ever so slightly to the case where W1 still has a lower RLCT, but it has marginally worse accuracy than W−1 and thus w(0)1 is not a true parameter, but is an optimal parameter within W1. We will set

L(w(0)−1)=S,andL(w(0)1)=S+Cfor some constant C>0. Our KL divergence is then given by

K(w)=(w+1)2((w−(1+hC))4−kC)where hC and kC are constants chosen such that w(0)1=1 is a local but not global minima of K(w), so K(1)=C and K′(1)=0.

Then by the free energy formula [13],

Fn(W−1)=nS+12logn,Fn(W1)=n(S+C)+14logn.We can visualise how this changes the loss landscape:

Animation 2: At low n the simpler model is preferred, but as n→∞, the true parameter is preferred

Let's visualise how the posterior concentration changes with n for C=0.1 and δ=0.5 (yes, δ is reasonably large here, but you want to be able to see this process, right?).

For the first few values of n, the free energy is minimised by W1 with its lower RLCT. But at about n≈17 the inaccuracy of W1 has become too great to bare and the more accurate W−1 is preferred. After this point the free energy curves are monotonic - the more accurate model will be preferred for all n>17.

Asymptotic Analysis Requires Care

I know what you're thinking: how come we could just approximate K(w) in each region? Don't other curvature effects matter to the posterior density too? Like the prior, and those Taylor coefficients in K(w)? Wait, and don't we care about Kn(w) instead of K(w)? Wait wait, Kn(w)=Ln(w)−Sn, but we never have access to Sn, so why would we care about Kn(w), let alone K(w)? This all seems far too contrived...

Yes, and no. Remember, the free energy formula gives us an asymptotic approximation of the posterior density has n→∞. Thinking carefully about asymptotic approximations does require some care, particularly when one tries to convert these formulas into statements about finite n - after all, we can only ever train a model on a finite number of datapoints. But Watanabe's free energy formula tells us what aspects of the geometry of K(w) affect the learning process as more data is collected. He is able to rigorously prove that the structure of singularities, as measured by the RLCT, are central to the long-term behaviour of model training. Yes, many other effects get thrown away in the O(1) term of the free energy formula, and the sequence Un is also loaded with other random fluctuations, but Watanabe nonetheless shows what makes singular models so powerful.

Where are we going from here?

In this post, we have argued for the shift in perspective from points to local neighbourhoods (frequentist to Bayesian statistics), and then from local neighbourhoods to singularities of K(w) (classical learning theory to singular learning theory). We have gone from caring about an enormous parameter space W, to only caring about certain singularities. Since singularities have different local geometry, and local neighbourhoods around them minimise the free energy, we have found our phases of statistical learning:

Phases in learning⟺Local regions W⊂Wcontaining a singularity of interest w(0).We will explain this correspondence between phases and singularities in detail in DSLT4. Before that, though, in DSLT3 we are going to study the set of true parameters W0 of a particular toy model: two layer feedforward ReLU neural networks with two inputs and one output. In doing so, we will see how the singularities of K(w) in these models are identifiable with the different functionally equivalent symmetries of the neural network. With a full classification of W0 in hand, we will then look at some experiments on these toy models that provide tractable and precise illustrations of phase transitions in the posterior in these ReLU neural networks, which Watanabe's free energy formula predicts.

References

[Wat09] S. Watanabe Algebraic Geometry and Statistical Learning Theory 2009

[Wat13] S. Watanabe A Widely Applicable Bayesian Information Criterion 2013

[Wat18] S. Watanabe Mathematical Theory of Bayesian Statistics 2018

[Lin11] S. Lin Algebraic Methods for Evaluating Integrals in Bayesian Statistics 2011

In other words, the true distribution is q(y|x)=N(x2,1). ↩︎

In other circumstances without a closed-form solution we can use an optimisation method like SGD.

Precisely,

Ln(w)=1nn∑i=112∥yi−f(xi,w)∥2M+M2log2π,where M is the dimension of the output y∈RM. ↩︎

In the sense that if we kept drawing more data from the truth q(y|x), the error of f15(x) would get worse and worse - it is overfitting data. ↩︎

Okay, so this is a bit of a white lie. If the model and truth are both defined by a regression model with equal variance σ2=1, then

K(w)=12∫RN∥f(x,w)−f(x,w0)∥2Mq(x)dx.I haven't checked the case where the variances are different, but I believe it only requires a slight adjustment to this formula with a scaling factor somewhere. But this example nonetheless illustrates the point - K(w) is a paraboloid in regular models.

Lemma 3.5 of my thesis. ↩︎

The reason this works is because of the asymptotics of log(n+1)−logn.

Originally, in [Wat09], Watanabe proves the formula for the realisable case where w(0)∈W0 is a true parameter, meaning K(w(0))=0 and Ln(w(0))=Sn.

[Wat18, Def 7, Chap 3] For a given pair w0∈Wopt and w∈W, the log density ratio function is defined by

f(x,w0,w)=logp(y|x,w0)p(x|w).If there exists c0>0 such that for any arbitrary pair w0∈Wopt and w∈W

EX[f(X,w0,w)]≥c0EX[f(X,w0,w)2],then it is said that the log density ratio function f(x,w0,w) has a relatively finite variance. ↩︎

And if it achieves the maximum multiplicity, but we will leave this vague to avoid more technical clutter.

In fact, this analogy to statistical physics runs quite deep. Hamiltonian Monte Carlo, one of the main methods for sampling from a Bayesian posterior, is essentially just simulating a particle subject to a Gibbs distribution e−H(w). There's a reason we've been calling it the free "energy", after all! ↩︎

Specifically, as n→∞, the KL divergence converges,

Ln(w)−Sn=Kn(w)→K(w)=L(w)−S.Since S is a constant, we are able to write

p(w|Dn)=φ(w)e−nLn(w)∫Wφ(w)e−nLn(w)dw≈φ(w)e−nL(w)∫Wφ(w)e−nL(w)dwenSenS=φ(w)e−nK(w)∫Wφ(w)e−nK(w)dw.If one defines the posterior in terms of Kn(w), we call this the normalised posterior.

For this pathological example, these formulas are certainly not an adequate approximation for the exact numerical free energy at low n - for one thing, they don't even depend on the radius of the ball δ. However, writing the formulas like this does point us towards the conceptual idea, which is verified in the below animations.