I don't think Pratchett was seriously advancing the theory as an explanation for why some people are much richer than others. I'm not sure he was even intending to represent Vimes as doing that, even though that's what the words literally say. Vimes is a policeman, not a logician or a philosopher, and this is just a passing thought. And Pratchett was a writer (writing humorous fantasy rather than, say, political philosophy or economics), and plausibly prioritizing vividity over precise accuracy.

Vimes, in-story, is obviously aware that Sybil Ramkin has a vast amount of inherited wealth that far outweighs any benefit she might have obtained from being able to spend less by buying higher-quality things with higher up-front costs.

So when you protest that people

don't seem to realize that the thing they're quoting is saying "rich people spend less money than poor people, and that's why they're rich"

I think you're being unfair. Yes, that's what the thing they're quoting literally says. No, that's not sufficient reason to think that it's exactly what Pratchett's character meant, still less to think that it's exactly the point Pratchett himself was meaning to make.

For what it's worth, I'm pretty sure that (1) Pratchett's actual opinion on this is roughly what the Wikipedia article says, (2) to whatever extent he thought it through explicitly, Pratchett's intention was to describe Vimes as having the same idea in a crude, very concrete, not highly analysed form, and (3) he worded it the way he did because he was aiming for something vivid and punchy, not because that wording was the most precise expression of the actual idea. And (4) I am very confident that Pratchett did not in fact think that being able to spend less for this sort of reason is the cause or even one of the main causes of rich people's richness, and fairly confident that if you'd asked him what he imagined Vimes as thinking he would have said Vimes didn't really think that either.

Similarly, when in Carpe Jugulum Granny Weatherwax tells a hapless young Omnian priest "sin is treating people as things, and that's all there is to it"[1] I don't think we should actually take Pratchett to be seriously claiming, or even to be representing E.W. as seriously claiming, that there is literally no other moral principle besides "don't treat people as things".

[1] Those aren't the exact words, I'm not sure it's in Carpe Jugulum, and I'm not 100% sure the other party is an Omnian priest. But, in each case, close enough.

In terms of your earlier article: I am very confident that Pratchett's actual opinion was much more "level 1" than "level 3" despite the literal sense of the words he described Vimes's thoughts with.

(It's definitely true that some people who talk about "boots theory" mean something different from what Pratchett meant, but that always happens.)

Similarly, when in Carpe Jugulum Granny Weatherwax tells a hapless young Omnian priest “sin is treating people as things, and that’s all there is to it”[1] I don’t think we should actually take Pratchett to be seriously claiming, or even to be representing E.W. as seriously claiming, that there is literally no other moral principle besides “don’t treat people as things”.

According to this reddit thread, the full quote is

"There's no grays, only white that's got grubby. I'm surprised you don't know that. And sin, young man, is when you treat people like things. Including yourself. That's what sin is."

"It's a lot more complicated than that--"

"No. It ain't. When people say things are a lot more complicated than that, they means they're getting worried that they won't like the truth. People as things, that's where it starts."

"Oh, I'm sure there are worse crimes--"

"But they starts with thinking about people as things..."

(And yes, it's Carpe Jugulum.)

I feel like you're saying "okay, but she's not really saying...." And the E.W. in my head is glaring at you because she just explained that yes she is really saying.

So, first of all, she begins by saying "sin is ..." but when pushed a bit she falls back to "that's where it starts". And, second, if e.g. you cornered her and said "look, here's a case where someone did something awful to someone else, not because he treated her like a thing but because he treated her like a person but one much less important than himself" the answer would be more like "well, that's just a watered down version of treating people as things" or "yes, fair enough, but it's very much the same sort of failure" than like "if he didn't literally treat her as a thing, then he wasn't doing anything wrong".

To be clear, I am not saying that what E.W. says to the priest is wrong, I'm saying it's not intended to be taken strictly literally, just as the great majority of things people say aren't intended to be taken strictly literally. And I think the same thing applies to Vimes saying "the reason that the rich were so rich was that they managed to spend less money".

So my read is "E.W. is actually claiming that sin is just treating people like things. She doesn't want the listener to tone it down to some less absolute position."

Maybe the listener gets closer to the truth by doing that. But it's not what E.W. intends. If the listener gets closer to the truth by adding nuance, then E.W. loses points both for being wrong and for interrupting to say "no nuance!" If E.W. herself tones it down while saying "no nuance!" then, well, let's notice this and let it affect how seriously we take her in future.

(This doesn't apply to Vimes, who was never challenged; or to Pratchett, who should not in general be assumed to endorse things his characters say.)

Vimes, in-story, is obviously aware that Sybil Ramkin has a vast amount of inherited wealth that far outweighs any benefit she might have obtained from being able to spend less by buying higher-quality things with higher up-front costs.

Vimes obviously should be aware of this. I'm not super confident that the passage in question was written with Pratchett being aware of Vimes being aware of it.

So when you protest that people

don’t seem to realize that the thing they’re quoting is saying “rich people spend less money than poor people, and that’s why they’re rich”

I think you’re being unfair. Yes, that’s what the thing they’re quoting literally says. No, that’s not sufficient reason to think that it’s exactly what Pratchett’s character meant, still less to think that it’s exactly the point Pratchett himself was meaning to make.

Oh, I don't think people should think that either Vimes or Pratchett believed the literal words.

But I'd still like if they noticed that the literal words say something very different than their interpretation.

For what it’s worth, I’m pretty sure that (1) Pratchett’s actual opinion on this is roughly what the Wikipedia article says,

Why are you pretty sure of this? (And, do you mean the definition that the Wikipedia article gives, along with examples that don't match the definition; or do you mean that Pratchett would think of Wikipedia's examples as being examples of the concept, and Wikipedia's definition is unnecessarily limited?)

Why do you think Pratchett was thinking something similiar to Wikipedia, and not instead

- an explanation not of why the rich are rich, but why the poor stay poor

- why being poor sucks so badly

- buying in bulk

- even someone with only (modern numbers) $500,000 in assets (house, car, stuff, some investments) and a part time non-profit job that pays $25,000 a year is going to live a more comfortable life than someone in Vimes position of ~$1,000 in assets and $75,000 a year

- When the author labels it a "theory of socioeconomic unfairness," he's being deeply ironic. You'd expect that analyzing one's own economic problems would help them to solve them. Instead, Vimes' theories seem to be keeping him poor.

- If you broaden it to include expenditure and accumulation of all resources, not just money, then it's mostly true.

- every place where rich people are able to become richer because they have more money to start out with

(Guess: perhaps you think some of these are "close enough to Wikipedia that it's fine to use one name to refer to the vague cluster", and the rest are "obviously silly"?)

(It’s definitely true that some people who talk about “boots theory” mean something different from what Pratchett meant, but that always happens.)

I think it happens more with "boots theory" than other things, and I think "~no one interprets it literally" is a large part of that. ("Non-literal interpretations" is a much broader space than "literal interpretations".)

Aside, a comment I previously left:

My intent was to talk about how it's interpreted by internet culture, not how Pratchett originally intended. E.g. I quote quora users discussing it, and only briefly nod towards what Pratchett might have meant. In hindsight I think I should have been clearer about that. There's a few comments (here and on LW) saying what Sam Vimes would have been thinking, and while that's interesting, it doesn't seem super relevant to me and I'm not sure if the commenters think it's particularly relevant or just an interesting aside. (I certainly don't object to interesting asides!) My position is something like...

One can reasonably ask what Sam Vimes believed; and what Pratchett himself believed; and whether the literal words are a good description of those beliefs; and if not, whether that was deliberate on Pratchett's part; and what was actually true of Ankh-Morpork; and so on. But while those are reasonable questions to ask, none of them seem super relevant to how boots theory is used today. (Some of them might bear on how we think of Pratchett as a writer or thinker, but I'm not trying to judge Pratchett.) When it was originally written, it was written in service of storytelling. When it's used today, it's used to explain an economic phenomenon, so it needs to satisfy different constraints. If it does badly at that, which I think it does for reasons explained in the post, then it shouldn't be used for that purpose.

Maybe I should have been clearer this time, too.

But I'd still like if they noticed that the literal words say something very different than their interpretation.

I think most people most of the time don't particularly pay attention to what the literal words say. Sometimes that's a serious failing. It can bite you pretty hard if the words were written with careful attention to the literal meaning and you're trying to get their consequences right. But when (as, I think, in this case) that's not how the words got the way they did, I find it hard to be greatly bothered when people attend to the underlying meaning rather than the strict literal meaning.

Why are you pretty sure of this?

I'm not sure I can give much of an answer to that. Handwavily: because that sort of opinion seems both (1) an opinion Pratchett might plausibly have had and (2) one that might plausibly have led him to write what he did, whereas e.g. the literal reading that you call "level 3" in your earlier post does a bit better on #2 but to my mind much worse on #1.

And, do you mean [...]

I mean the definition at the start of the Wikipedia article. And I think

- that definition doesn't attempt to nail the theory down as specifically explaining "why the rich are rich" or "why the poor stay poor"; I think G.S.W. is offering not a different definition of "boots theory" from Wikipedia's but a different view from the literal one of what phenomena the (same) theory is explaining

- the same goes for "why being poor sucks so badly"

- "buying in bulk" is related but I don't find it plausible that either Pratchett or Vimes had that specifically in mind since the single example Vimes gives is of something that isn't buying in bulk -- but the idea "if you can afford to spend more then you can spend less in the long run" covers both buying in bulk and buying higher-quality items so this is definitely part of the same "vague cluster"

- Ericf's thing about assets versus income has some relationship to what I take Vimes/Pratchett to have been saying but I think that if Vimes/Pratchett had been thinking specifically of that then again Vimes would have picked a different example (something like Sybil never needing to buy furniture because she has a house full of high-quality furniture that's been in the family for centuries, perhaps)

- DirectedEvolution's take isn't really (I think) disagreeing about what Vimes's theory says, he's just saying that it's stupid and so Pratchett can't really believe anything like it is right. (I think that even if that's so Vimes's theory is still one of "socioeconomic unfairness" and if Pratchett is being ironic in using those words it's not because they misrepresent what Vimes is thinking.) I don't have very strong opinions as to how good a theory Pratchett actually thought it was, but I think it's unlikely that he thought it as bad as DE does.

- jimrandomh's generalization doesn't purport to be what either Vimes or Pratchett meant, I think. He's proposing a Generalized Boots Theory for which something like your "level 3" might be true.

- I'm not sure whether gbear605 is actually saying that Vimes or Pratchett really meant his (different) Generalized Boots Theory -- his literal words do imply that, but just as with Pratchett himself I question whether he would endorse that if pushed -- but this too seems like a reasonable generalization of the Vimes/Pratchett theory

so, broadly, yes I think most of these are in the same "vague cluster"; for the most part I wouldn't myself endorse saying "boots theory is ..." about them but doing so doesn't seem entirely perverse to me.

When it's used today, it's used to explain an economic phenomenon [...] If it does badly at that, which I think it does [...]

I'm not sure what explanation of what economic phenomenon you're saying "boots theory" is today used to mean. Your examples suggest that in fact it's used in a wide variety of ways to describe and/or explain a wide variety of things.

Your earlier article (unlike this one) seems mostly to be claiming that the theory is generally offered as an account of why rich people are rich. I agree that it isn't in fact a good account of that. I am not at all persuaded that people talking about "boots theory" commonly mean to claim that it is.

This article (unlike the earlier one) seems mostly to be pointing out that people use the term in a wide variety of ways -- mostly not claiming that being able to buy better-quality stuff is why rich people are rich. (Indeed, above you suggest that they haven't even noticed that interpretation of the theory, which is pretty much opposite to the position in your earlier post,) I haven't myself made any serious attempt to survey how the term is used in practice. It may well be as varied as you say. My purely-handwavy-anecdotal impression is that most uses of the term are in the "vague cluster" that can be decently described with the words at the start of the Wikipedia article, and (like you, IIUC) I think that many such uses -- corresponding to your "level 1" or less frequently your "level 2" -- are saying something that's fairly clearly true.

I find it hard to be greatly bothered

I think it's very reasonable not to be greatly bothered by this.

I do think it matters a little bit. If people are talking about "boots theory" and don't mean the same thing, they're going to communicate less well than if they unpack their definitions.

But I absolutely think of this as a hobby horse of mine. I do fully recommend that people avoid using the term "boots theory", because it's unclear. But I'm not trying to recruit people into a crusade against it.

I'm not sure what explanation of what economic phenomenon you're saying "boots theory" is today used to mean.

I mean that there's no single economic phenominon it's today used to explain. When people talk about "boots theory", it's not clear what they mean, and that's a problem when they're trying to explain something.

Your earlier article (unlike this one) seems mostly to be claiming that the theory is generally offered as an account of why rich people are rich.

Ah, that wasn't my intent. My earlier article was claiming (among other things) that the theory as written is an account of why rich people are rich, whether or not people offer it as that. It didn't take a strong position on how people do in fact offer it; in this article I've looked at that question in more detail.

In-book it's explicitly partly about inherited wealth; the passage wherein Vimes formulates his theory is preceded by a section about how the very richest people, like Lady Sybil, can afford to live as though poor in some ways (wearing her mother's hand-me-downs, etc) and is immediately followed by this:

The point was that Sybil Ramkin hardly ever had to buy anything. The mansion was full of this big, solid furniture, bought by her ancestors. It never wore out. She had whole boxes full of jewelery which just seemed to have accumulated over the centuries. Vimes had seen a wine cellar that a regiment of speleologists could get so happily drunk in that they wouldn’t mind that they’d got lost without trace.

Lady Sybil Ramkin lived quite comfortably from day to day by spending, Vimes estimated, about half as much as he did.

Lady Sybil Ramkin lived quite comfortably from day to day by spending, Vimes estimated, about half as much as he did.

As the previous post points out, she obviously didn't.

If I had to guess: I think the way prepaid meters work is you go to a shop and buy a physical object representing a certain amount of electricity and present that physical object to your electric meter.

I've used a pre payed meter. The way it worked was I went to their webpage and bough the amount I wanted. This was mean to update the meeter automatically within an hour, but this never worked, so I had to use the backup method wich was to enter a very long numerical code into the meter.

Oh, interesting. When I had a prepaid meter (2016ish) I went to a shop, but I'm not sure if buying it online wasn't an option at the time or just no one told me about it.

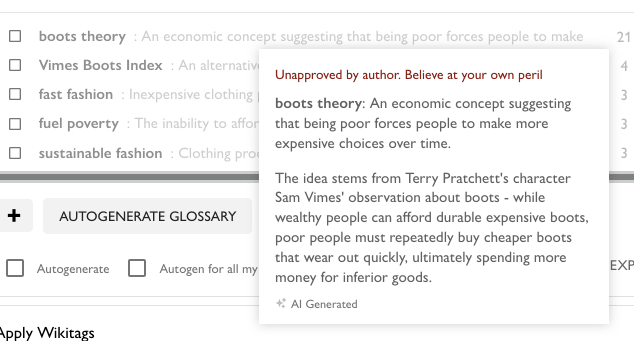

I've previously complained about how people often repeat a quote that starts with

(Terry Pratchett, Men at Arms)

…and then don't seem to realize that the thing they're quoting is saying "rich people spend less money than poor people, and that's why they're rich". It seems to me that people interpret it as saying various different things, but rarely the thing it's quite obviously saying.

Here's an oversight in my previous complaint: I didn't look at Wikipedia. I picked up vibes from a few internet randos, but not the specific internet randos who edit the world's premier encyclopedia.

Part of what I want to point out here is "there's no consensus on what the term boots theory refers to". If I'm wrong about that, and just happened to read the wrong internet randos, it seems likely that Wikipedia will tell me what the consensus is. So let's take a look.

As I write, the most recent revision is from March 17 2025, and it tells us:

Come to think of it, this is actually a stronger claim than what I called level 1 boots theory. I described that as "being rich enables you to spend less money on things", but this is a specific way that being rich enables you to spend less money on things. Maybe it is worth having a term for this distinct from "ghetto tax", which is what I suggested previously. (But that term shouldn't necessarily be "boots theory".)

So that's what Wikipedia says "boots theory" refers to. Let's follow its citations and see why Wikipedia says that.

Wikipedia:

This doesn't talk about boots theory at all, but following the citations anyway:

[1] is The Guardian, Terry Pratchett estate backs Jack Monroe's idea for 'Vimes Boots' poverty index. This is an article about someone named Jack Monroe creating a price index, intended as an alternative to CPI, and naming it the "Vimes Boots Index".

As a source for Wikipedia's claim, the relevant part of this is quoting Rhianna Pratchett, who says:

I note pedantically that Commander is a different rank than Captain. (Vimes is promoted from Captain to Commander in Men at Arms.)

On the subject of boots theory, we have the original quote from Men at Arms, starting (as usual) with "the reason that the rich were so rich". Rihanna calls it a "musing on how expensive it is to be poor via the cost of boots".

We're not told how the index is calculated or how it relates to boots theory except that it's "named in honour" of it.

(Incidentally, Monroe's own Wikipedia page doesn't mention the Vimes Boots Index at all.)

[2] is an NYT financial advice column, I think? Spend the Money for the Good Boots, and Wear Them Forever. It mostly boils down to someone giving an example where buying an expensive thing now saved money in the long run compared to buying cheap things. He bought $300 ski pants that have lasted 17 years and counting, and claims that if he'd bought $50 ski pants instead, he'd have had to buy a new pair every year, spending over $800.

Note, there's an important calculation that he skips. If he'd invested $300 in the S&P 500 in 1999, this site claims it would have been worth $762 nominal in 2016, or $528 inflation-adjusted. So yes, if he has the numbers right, it seems like this was probably a good financial investment on his part.

Anyway. This article does back the cited claim (albeit without using the phrase "City Watch"). On the subject of boots theory, it includes the original quote (starting, as usual, with "the reason that the rich were so rich") and doesn't take it any further than "you can spend more money now to spend less money in total". The example it gives matches Wikipedia's definition of boots theory.

Back to Wikipedia:

We just discussed [2]. [3] is Gizmodo, Discworld's Famous 'Boots Theory' Is Putting a Spotlight on Poverty in the UK. This is another announcement of the Vimes Boots Index. It gives a little more detail on how it relates to boots theory:

…except that I don't see much connection. But boy, impressive segue in that second sentence.

Wikipedia now gives the original quote, starting as usual with "the reason that the rich were so rich". This is citation 4, pointing at Men at Arms. Then:

[5] is the New Statesman, Your best ally against injustice? Terry Pratchett. This is another piece talking about the Vimes Boots Index. It gives an extra hint about how it's calculated:

On the subject of boots theory, we get the original quote, refreshingly not starting with "the reason that the rich were so rich" - it starts with "take boots, for example". As commentary, it says "being poor is actually more expensive than being wealthy".

(That sounds a lot like "poor people spend more money than rich people", but they're not quite the same. If I say "owning an Aston Martin is more expensive than owning a Ford", you probably assume that the cost of driving, maintaining and insuring a Martin in some minimal adequate condition is higher than doing that for a Ford. But some people will voluntarily spend more than the minimum, and some Ford owners will spend more on their cars than some Martin owners; and Ford owners may well spend more than Martin owners on non-car stuff. So it would be coherent to say something like: "being poor is more expensive than being rich, in the sense that poor people are forced to spend more money on daily living activities. But rich people typically spend more than they're forced to, and more than poor people overall, on daily living activities and other stuff." I'm not sure if I've previously realized this distinction.)

Wikipedia:

[6] is just a link to page 180 of that book. It doesn't have much more than what Wikipedia gives:

This might be the shortest extract of the quote I've seen yet.

("Particularly relevant" seems to come from a footnote on page 213. I can locate it through search but there's no preview available for the page.)

Wikipedia:

This seems to switch the idea from "in the long run, repeatedly buying cheap things costs more than buying expensive things" to "buying things with money you don't hand over yet costs more than buying things with money you hand over immediately". Or, "people won't typically lend you money for free".

The article (ConsumerAffairs, Fingerhut boots and the Vimes' Boots paradox) even notices this leap. ("though we haven't tested this ourselves, we're sure that Carrini boots or Reebok sneakers bought from Fingerhut are just as good as Carrini or Reebok items bought elsewhere.)

We're given the original quote, starting as usual with "the reason that the rich were so rich".

Wikipedia:

Dorset Eye, Mike Deverell discusses five reasons why those with less end up paying more.

Welp, uh, this is kind of a case where people will lend you money for free, if you have money.1 It fits a broad "being poor is expensive" narrative, but it's not a case where rich people buy a more expensive thing up front to save money in the long run.

Other than fuel poverty, the article gives four more reasons "why it's so difficult to climb out of the poverty trap": VAT, other taxes, food poverty and austerity. None seem to have any relation to boots theory. The article doesn't explicitly say they're examples of it, and Wikipedia doesn't mention them, so I'll leave them out.

We get the original quote, starting with "the reason that the rich were so rich".

Wikipedia:

Stitching a new narrative: engaging with sustainability in the fashion industry. The relevant part is:

Followed by the original quote, starting as usual with "the reason that the rich were so rich".

So this broadly matches Wikipedia's description of the term. It doesn't come right out and say "buying the expensive t-shirt is cheaper in the long run". But it's at least hinting in that direction.

Wikipedia:

Tribune, The Price of Poverty. This one doesn't give the original quote at all, describing boots theory in its own words:

(I repeat that Vimes is wrong about the nobility - at minimum, about the specific nobility he's thinking of, who is the richest woman in the city and his fiancée - spending less money than him.)

Here are the examples the article gives:

Roughly speaking, I think the idea here is "rich people's cost of living is going down and poor people's is going up". But that's talking about acceleration, not velocity.

So this is "spending more money up front is cheaper in the long term". You can even kind of make it fit the original definition: when you rent, you repeatedly purchase "the right to live in this place for the next month", but when you buy, you purchase that right once and keep it indefinitely. And the rights you purchase when you rent are typically worse than the rights you purchase when you buy (e.g. more restrictive about pets, or decoration, or interior layout).

(Note: costs of home ownership here do take into account "interest lost by paying a deposit rather than saving.")

"Poor people get less favorable terms when borrowing money."

"Poor people don't get enough food, and that causes them long term problems."

"Poor people are less healthy, and more expensive for the government to provide healthcare to."

Remember that Wikipedia's definition is

Of the citations, it seems like three back this up? One with an example about ski pants, one with an example about t-shirts, and one talking about home ownership versus renting.

Other than those, here are some things that citations relate to boots theory:

…and for some of these, Wikipedia even includes them inline. You don't need to click through to the citations to realize that multiple different concepts are getting confused.

(Someone in the talk page has noticed the same thing: "The instances listed here aren't really examples of the same mechanism.")

(Also, when I wrote the previous essays, multiple commentators told me what they take boots theory to mean, but none of them picked Wikipedia's definition of it.)

So I think I'm vindicated in my complaints. Wikipedia's definition of "boots theory" is not consensus, even among Wikipedia's sources. There is no consensus.

I'm not sure I fully understand what's going on here, but I think roughly speaking, there are three ways to pay for electricity and gas.

Direct debit, where you pay a fixed amount each month. They'll try to calculate it so you pay the same amount every month, even though you don't use the same amount every month. So over time you'll build up a credit or debit, and if that gets too large they'll adjust your payments.

Quarterly, where every quarter you pay for the electricity you used in the last quarter.

Prepaid, where you have to pay for the electricity you use before you use it.

(a) is substantially cheper than (b), which is marginally cheaper than (c). But (a) and (b) are only available if the electric company trusts you to pay for electricity you've already used.

Why these price differences? I don't know. If I had to guess: I think the way prepaid meters work is you go to a shop and buy a physical object representing a certain amount of electricity and present that physical object to your electric meter. That probably has higher transaction costs than direct debit or quarterly bank transfers. And direct debit sometimes involves you lending them money, so they'll pay you for that; and I expect it's more reliable from their perspective than quarterly payments. ↩