I have a vague memory of a dream which had a lasting effect on my concept of personal identity. In the dream, there were two characters who each observed the same event from different perspectives, but were not at the time aware of each other's thoughts. However, when I woke up, I equally remembered "being" each of those characters, even though I also remembered that they were not the same person at the time. This showed me that it's possible for two separate minds to merge into one, and that personal identity is not transitive.

So if you rejected mind-body continuity, you'd have to admit that some non-infinitesimal mental change can have an infinitesimal (practically zero) effect on the physical world. So basically you'd be forced into epiphenomenalism.

I don't think there's a principled distinction here between "infinitesimal" and "non-infinitesimal" values. Imagine we put both physical changes and mental changes on real-valued scales, normalized such that most of the time, a change of x physical units corresponded to a change of approximately x mental units. But then we observe that in certain rare situations, we can find changes of .01 physical units that correspond to 100 mental units. Does this imply epiphenomenalism? What about 10^(-3) -> 10^4? So it feels like the only thing I'm forced to accept when rejecting the continuity postulate is that in the course of running a mind on a brain, while most of the time small changes to the brain will correspond to small changes to the mind, occasionally the subjective experience of the mind changes by more than one would naively expect when looking at the corresponding tiny change to the brain. I am willing to accept that. It's very different from the normal formulation of epiphenomenalism, which roughly states that you can have arbitrary mental computation without any corresponding physical changes, i.e. a mind can magically run without needing the brain. (This version of epiphenomenalism I continue to reject.)

Good point. I edited the post to say "near epiphenomenalism", because like you said, it doesn't fit into the strict definition.

If the physical and mental are quantized (and I expect that), then we can't really speak of "infinitesimal" changes, and the situation is as you described. (But if they are not quantized, then I would insist that it should really count as epiphenomenal, though I know it's contentious.)

Still, even if it's only almost epiphenomenal, it feels too absurd to me to accept. In fact you could construct a situation where you create an arbitrarily big mental change (like splitting Jupyter-sized mind in half), by the tiniest possible physical change (like moving one electron by one Planck length). Where would all that mental content "come from"?

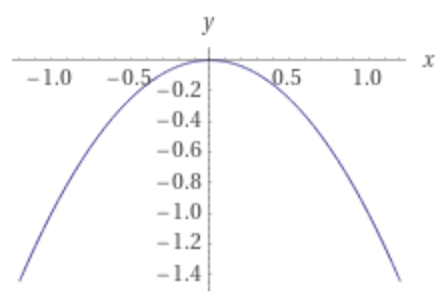

A ball sitting on this surface:

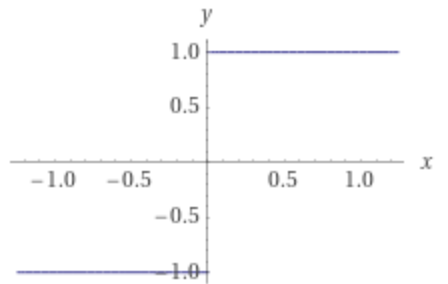

has a direction of travel given by this:

In other words, continuous phenomena can naturally lead to discontinuous phenomena. At the top of that curve, moving the ball by one Planck length causes an infinite divergence in where it ends up. So where does that infinite divergence "come from", and could the same answer apply to your brain example?

Here, to have that discontinuity between input and output (start and end position), we need some mechanism between them - the system of ball, hill, and their dynamics. What's worse it needs to evolve for infinite time (otherwise the end still continuously depends on start position).

So I would say, this discontinuous jump "comes from" this system's (infinite) evolution.

It seems to me, that to have discontinuity between physical and mental, you would also need some new mechanism between them to produce the jump.

we need some mechanism between them - the system of ball, hill, and their dynamics.

A brain seems to be full of suitable mechanisms? e.g. while we don't have a good model yet for exactly how our mind is produced by individual neurons, we do know that neurons exhibit thresholding behavior ('firing') - remove atoms one at a time and usually nothing significant will happen, until suddenly you've removed the exact number that one neuron no longer fires, and in theory you can get arbitrarily large differences in what happens next.

I thought about it some more, and now I think you may be right. I made an oversimplification when I implicitly assumed that a moment of experience corresponds to a physical state in some point in time. In reality, a moment of experience seems to span some duration of physical time. For example, events that happen within 100ms, are experienced as simultaneous.

This gives some time for the physical system to implement these discontinuities (if some critical threshold was passed).

But if this criticality happens, it should be detectable with brain imaging. So now it becomes an empirical question, that we can test.

I still doubt the formulation in IIT, that predicts discontinious jumps in experience, regardless of whether some discontinuity physically happens or not.

(BTW, there is a hypothetical mechanism that may implement this jump, proposed by Andres Gomez Emilsson - topological bifurcation.)

Hm, yeah, the smallest relevant physical difference may actually be one neuron firing, not one moved atom.

What I meant by between them, was that there would need to be some third substrate that is neither physical nor mental, and produces this jump. That's because in that situation discontinuity is between start and end position, so those positions are analogous to physical and mental state.

Any brain mechanism, is still part of the physical. It's true that there are some critical behaviors in the brain (similar to balls rolling down that hill). But the result of this criticality is still a physical state. So we cannot use a critical physical mechanism, to explain the discontinuity between physical and mental.

I'm glad that you identified these two postulates, but I am pretty certain that P1 does not hold in principle. In practice it probably holds most of the time, just because systems that are highly discontinuous almost everywhere are unlikely to be robust enough to function in any universe that has entropy.

Note that continuous physical systems can and frequently do have sharp phase transitions in behaviour from continuous changes in parameters. From a materialistic view of consciousness, those should correspond to sharp changes in mental states, which would refute P1.

That's a good point. I had a similar discussion with @benjamincosman, so I'll just link my final thoughts: my comment

Alarmed that with all this talk of anthropics thought experiments and split brains you don't reference Eliezer's Ebborian's Story. (Similarly, when I wrote my anthropics thought experiment (Mirror Chamber (as far as I can tell it's orthogonal and complementary to your point)) I don't think I remembered having read the Ebborians story, I'm really not sure I'd heard of it).

Oh, I've never stumbled on that story. Thanks for sharing it!

I think it's quite independent from my post (despite such a similar thought experiment) because I zoomed in on that discontinuity aspect, and Eliezer zoomed in on anthropics.

It's a very interesting point you make because we normally think of our experience as so fundamentally separate from others. Just to contemplate conjoined twins accessing one anothers' experiences but not have identical experiences really bends the heck out of our normal way of considering mind.

Why is it, do you think, that we have this kind of default way of thinking about mind as Cartesian in the first place? Where did that even come from?

I imagine that shared bodies with shared experiences are difficult to coordinate. If you have two bodies with two brains, they can go on two different places, do two different things in parallel. If you have one body, it can only be at one place and do one thing, but it's perfectly coordinated. One-and-half body with one-and-half brain seems to have all disadvantages of one body, but much worse coordination. Thus evolution selects for separate bodies, each with one mind. (We have two hemispheres, and we may be unconsciously thinking about multiple things in parallel, but we have one consciousness which decides the general course of action.)

We might try looking for counter-examples in nature. Octopi seem to be smart, and they have a nervous system less centralized than humans. They still have a central brain, but most of their neurons are in arms. I wonder whether that means something, other than that movement of an octopus arm is more difficult (has more degrees of freedom) than movement of a human limb.

Yeah right. There is something about existing within a spatial world that makes it reasonable to have a bunch of bodies operating somewhat independently. The laws of physics seem to be local, and they also place limits on communication across space, and for this reason you get, I suppose, localized independent consciousness.

It seems that we just never had any situations that would challenge this way of thinking (those twins are an exception).

This Cartesian simplification almost always works, so it seems like it's just the way the world is at its core.

This. It's why things like mind-uploading get so weird, so fast. We won't have to deal with now, but later that's a problem.

Agreed, but what is it about the structure of the world that made it the case that this Cartesian simplification works so much of the time?

It just looks that's what worked in evolution - to have independent organisms, each carrying its own brain. And the brain happens to have the richest information processing and integration, compared to information processing between the brains.

I don't know what would be necessary to have a more "joined" existence. Mushrooms seem to be able to form bigger structures, but they didn't have an environment complex enough to require the evolution of brains.

Basically, without mind-uploading, you really can't safely merge minds, nor can you edit them very well. You also can't put a brain in a new body without destroying it.

This the simplification of a separate mind works very well.

P1 sounds contra the evidences: when an action potential travels a myelinated axon, its precise amplitude does not matter (as long as it’s enough to make sodium channels open at the next Ranvier node). In other words, we could add or substrat a lot of ions at most of the 10^11 Ranvier nodes of the human brain without changing any information in mind.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saltatory_conduction https://bionumbers.hms.harvard.edu/bionumber.aspx?s=n&v=5&id=100692 https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Node_of_Ranvier

However I didn’t get how you went from « tiny physical changes should correspond to tiny mental changes » (clearly wrong from above, unless tiny includes zero) to « non-infinitesimal mental change can have an infinitesimal (practically zero) effect on the physical world », so maybe I’m missing your point entirely. Could you rephrase or develop the latter?

Yeah, when I thought about it some more, maybe the smallest relevant physical change is a single neuron firing. Also with such a quantization, we cannot really talk about "infinitesimal" changes.

I still think that a single neuron firing, changing the content of experience so drastically, is quite hard to swallow. There is a sense in which all that mental content should "come from" somewhere.

I had a similar discussion with @benjamincosman, where I explore that in more detail. Here are my final thoughts from that discussion.

I'd like to share a simple thought experiment that has some pretty strange implications. It seems to show that the world cannot always be sharply divided into separate experiences.

We can make the analogy, to how the world cannot always be divided into separate organisms. Usually it can, but there are cases, like conjoined twins, where someone would say it's one organism, someone else that they are two organisms, and someone else that it's something in between.

The experiment lies on two postulates:

P1. Mind-body continuity

It's the idea that tiny physical changes should correspond to tiny mental changes. And that should work for arbitrarily tiny ones.[1] So you couldn't completely change the content of your experience, just by moving one atom in one of your neurons.

An infinitesimal physical change, will cause an infinitesimal change of that system's behavior. So if you rejected mind-body continuity, you'd have to admit that some non-infinitesimal mental change can have an infinitesimal (practically zero) effect on the physical world. So basically you'd be forced into near epiphenomenalism.

P2. Splitting the brain in half creates two separate experiences

This is illustrated nicely by the experiments with split brain patients (like this one). For example, if you had a split brain and closed your eyes, you couldn't tell if your right hand and left hand are touching the same surface. Those two experiences are separate[2] - they aren't unified into one, so you cannot compare them.

(It’s not relevant here if they should be treated as two persons. I only claim that they are two experiences.)

Experiment

Imagine that you undergo a brain-splitting surgery. You are anesthetized so you don't feel pain, but in this experiment, you're fully awake. And this surgery is very slow - they cut only one nerve fiber at a time.

At the beginning, you have one unified experience, but at the end you have two. So one possibility is that there was some exact point when the split occurred - some critical fiber that needed to be cut. But that would violate the mind-body continuity that we assumed. So the only alternative is that we gradually went from one to two experiences. That there was some "in-between" state.

What does it feel like?

So, how would it feel to be in such a state? Here is a real-life example of brain-conjoined twins where we may say that such "partially connected" experiencing happens. The blindfolded girl can access what her sister is seeing, but it's faint so she needs to focus.

Maybe it's just about how tightly bound the qualia are? So qualia of one sister are bound to the second one's, but very weakly. If that's true, this would make it much less exotic - in your ordinary mind you also have some qualia which are tightly bound, and some which are almost disconnected. For example, when you look at a tree:

Speculation

When you stop paying attention f.e. to your auditory field, could it be that it becomes disconnected from the main chunk of your experience (visual+thoughts+...), but those sound qualia maintain some "smaller" existence of their own?

Or that the dorsal visual stream (the one that is responsible for spatial understanding, and is separate from the object recognition stream) has its own "smaller" experiences?[3] Unfortunately, this stream is disconnected from your thoughts and episodic memory, so we don't have any easy way of checking that.

If we could identify some brain systems that are usually disconnected, but sometimes do connect, we could use @algekalipso's phenomenal puzzle test, to see if the other system has its own phenomenal experience.[4] But it may be impossible to find systems suitable for all the steps in that test.

Consequences

Integrated Information Theory, which is currently the most formally developed theory of consciousness, explicitly aims to divide the world into separate non-overlapping experiences (see Exclusion Postulate). The math used in that theory allows for situations, where an infinitesimal physical change results in a drastic mental change. It violates the "mind-body continuity"[5].

So maybe that Exclusion Postulate should just be dropped? The rest of the theory could still work without it. Instead of a set of separate experiences, the theory would output some more complex structure, maybe a graph[6]. For practical purposes, we could still cluster this graph into a set of separate experiences like before, but it should be clear that this is not what really exists. It’s just a practical simplification. And we could still quantify the amount of experience with a suitable graph metric.

So far, this mind fuzziness has never been a noticeable problem in real life. But brain-computer interfaces, mindmelding and digitalization of minds, will enable much more exotic mental architectures. This also complicates utilitarian calculations. But we can still aim for "the greatest good for the greatest number" - it's just that this number is no longer an integer.

Thanks to Kamil Przespolewski for all the help!

This postulate can be formalized analogously to Weierstrass's definition of a continuous function. So for an arbitrarily small mental change magnitude, you could find a physical change that produces a mental change with even smaller magnitude.

It is disputed if a complete disconnection happens in split-brain patients. Some information transfer may still be possible through the brainstem. But for our experiment it's enough to assume that this complete disconnection is possible in principle.

This would mean that blindseers have some visual qualia too, but they just cannot report it.

It may not be possible to freeze one of those systems, as the test requires, but at least we could distract it, to a similar effect.

Creators of IIT explicitly embrace this discontinuity. See endnote xii in their 2014 paper. Another discontinuity scenario for IIT is raised by Schwitzgebel here.

I expect this graph to represent the binding relations between qualia in some way. (Maybe a hypergraph would be more suitable.)