But solving for the higher numbers may also be harder. In the personal domain, many people find it easier to go on dates and find a partner they click with than to shift their attachment patterns or to achieve perfect enlightenment and become liberated from all suffering. A person’s external circumstances may also actively prevent them from making any internal progress, such as if their obligations keep them stressed all the time, or if they are in an abusive environment that actively punishes them for getting better.

Indeed, many people are unable to make progress on acceptance until they've dealt with enough of their immediate problems to have the space to start accepting. Acceptance is unthinkable because they feel so not-okay with anything.

I know that for myself I had to spend a lot of years "eating my shadow" before I had the capacity for anything more.

Very cool post, even if a bit lengthy! I’d suggest adding a small “Level 0”: sleeping well, staying physically healthy, and getting at least some support from other people. These basics often dissolve a surprising number of problems before anything deeper is needed.

I’d also emphasize that Levels 2–4 blend together quite a lot. If I’m understanding correctly, Level 2 resembles working with protectors in IFS, while Level 3 is closer to working with exiles. But in practice the boundaries blur: treating protectors with care often brings you into contact with exiles, which in turn requires the skill of “just being with” and to noticing Buddhist hindrances - something very similar to Levels 3 and 4, Healing exiles tends to clarify awareness, without which insight, steadier samadhi, and more authentic brahmavihāra practice are impossible. Those practices, in turn, necessarily involve meeting whatever emotions arise and transforming them in the process. So it’s not only that the levels reinforce one another; in some respects they’re almost facets of the same process.

I suppose it’s obvious I belong to the “emotional work” fan club 😁

Very cool post, even if a bit lengthy!

Thanks!

I’d suggest adding a small “Level 0”: sleeping well, staying physically healthy, and getting at least some support from other people.

I had a very brief mention of that at the very end, but yeah I could emphasize this more. The suggestion of level 0 is nice, though I'm not sure if that would cleanly fit the implied axis with the lower numbers being stuff that's easier to observe directly or externally and the higher numbers going toward more unconscious stuff that informs how things on the lower levels works out.

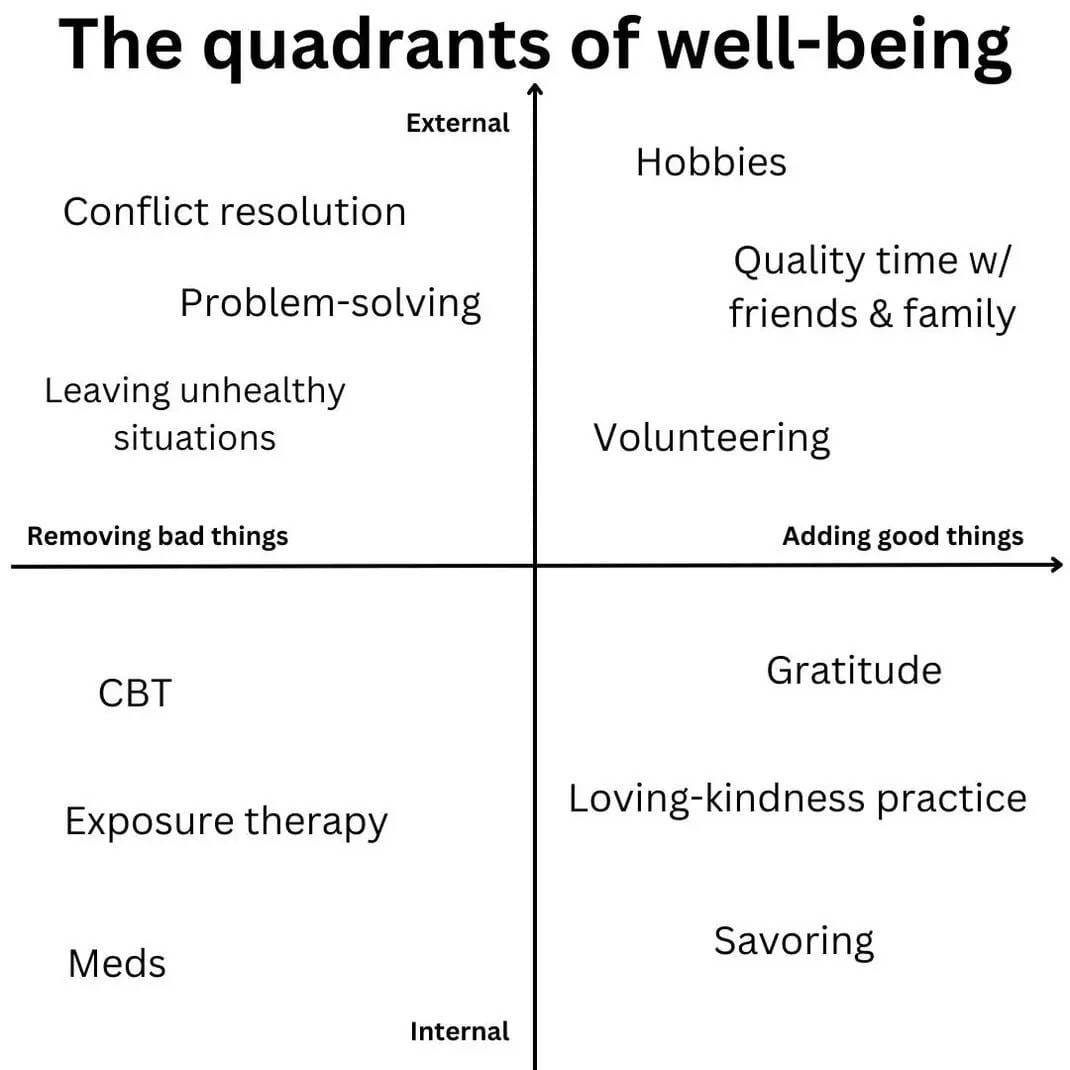

Then again maybe this kind of a quadrant approach (by Kat Woods) would work better than just one axis.

If I’m understanding correctly, Level 2 resembles working with protectors in IFS, while Level 3 is closer to working with exiles.

Yeah, a previous version actually had a footnote saying something like "for those familiar with IFS, we can roughly say that level 2 is protectors while level 3 is exiles". It got lost at some point while moving drafts from one file format to another.

So it’s not only that the levels reinforce one another; in some respects they’re almost facets of the same process.

Agree!

If you want to solve your emotional problems, how should you go about it?

I mean "emotional problems" in a broad sense, to refer to anything with an emotional component. This can be things that are obvious "emotional problems", like feeling excessively angry, anxious, or depressed. It can also mean things such as not feeling as motivated as you’d like. But I'm also covering problems that we wouldn't usually think of as emotional - basically anything from personal health issues to global poverty and existential risk.

To be clear, those are absolutely not purely emotional problems - they would be real issues that would need dealing with regardless of how you felt about them. But they have an emotional component, in that they will probably make you feel different things, and those feelings you feel may make it easier or harder to deal with the issues. For example, the thought of existential risks may be making you feel unsafe, and you’ll probably do a better job trying to stop them if you feel mostly safe rather than constantly anxious.

There are at least four different levels on which people like coaches, therapists, or spiritual teachers might approach an emotional problem that a client or student has. Different levels can be useful at different times, so it’s useful to be aware of all of them.

Let’s suppose that someone is single and has a thought that goes something like this:

I’ll go through different interventions based on which parts of that thought they target, and then discuss the levels more broadly.

Level 1: Action-oriented approaches

“How do I solve this problem directly?”

A client meets with a dating coach who reviews their online dating profiles. “These photos aren’t the best you can do, you’d look much better in a professional photoshoot”, the coach points out. “Here, I know a photographer I can recommend.” They role-play opening conversations, with the coach helping the client become a better conversationalist. Together, they create a list of interesting conversation starters and consider possible social events to attend.

A solution-focused therapist asks the client, "On a scale of 1-10, where 1 is completely unable to meet people and 10 is confidently dating, where are you now?" The client says 3. "What would need to happen for you to be at a 4?" The client mentions that they have been considering joining a hiking group. The therapist helps them break down the specific steps: finding the group's schedule, choosing a beginner-friendly hike, and preparing what to wear.

The action-oriented level takes the most straightforward approach: you think you can’t find a romantic partner, so let’s solve that problem by helping you find one. People focusing on this level typically assume that you already know what you need and just need help in figuring out how to get it.

This is the most obvious way to approach many problems. If there’s something you don’t have, figure out how to get it! This often works. Many people have lots of problems that they could solve if it just occurred to them to try doing something about them.

And even if trying to solve your problem directly hasn’t worked yet, maybe trying to solve it with more effort or thinking will help. Chris McKinlay set up a dozen bots to harvest a dating site for data, reprogrammed them to avoid detection when they started getting banned, extracted data from 25,000 dating profiles, did complicated data analysis to understand what kind of women there were in LA and what they cared about, and then used his data to go on dates with 87 people before finding the right person on the 88th date. Sometimes you just need more dakka. (At the same time, “just trying harder” is frequently a bad idea.)

Here are some indicators that an action-oriented approach might be a good fit:

Level 2: Blocker removal approaches

“What’s preventing me from pursuing solutions?”

A client has recently had bad experiences with dating and tells a cognitive-behavioral therapist that they don’t believe they can ever find a partner. The therapist asks them about their previous dating experiences and helps the client notice that they are catastrophizing based on their most recent date, and to remember that they’ve also had several good experiences. This gives them renewed hope.

A person messages their friend.

- “Hey this cute guy seems to like me back, should I ask him out? I’m scared!”

- “If he seems to like you back, what are you afraid of?”

- “Well what if he says yes?! I wouldn’t know what to do!”

- “You mean that a person you like might like you back? How horrible. 😉 Worst thing that could ever happen. Seriously, why would that be bad?”

- “I don’t know where it would lead! Like, if it does go well, what will we do after that?”

- “Only one way to find out! You don’t need to know in advance, you can just send him a message and see what happens.”

- “Okay you’re right. I’ll message him. Thanks so much. <3”

A client always seems to sabotage promising romantic connections after a couple of successful dates. A coherence therapist helps them uncover an emotional learning from childhood: “if I succeed at something important, mom feels that I don’t need her anymore and she gets depressed”. The therapist helps them integrate this with the client’s knowledge that they are an adult whose happiness doesn’t damage others, and the compulsion to sabotage romantic connections disappears.

The blocker removal level assumes that you have some kind of cognitive or emotional block that prevents you from thinking clearly about your goal. It’s not just that you don’t know how to find a partner; it’s that on some level, you believe that you can’t ever find one, or that it would be somehow bad for you if you did, etc. People focusing on this level typically still think that you are correct about what you need, but that some of your thinking around the topic is confused.

The basic assumption is that if this blocker is removed, you will then see things more clearly, stop sabotaging yourself, and become capable of achieving your goal of finding a partner. This doesn’t guarantee that you’ll know how to - you may still need the strategies from the action-oriented level - but at least it makes you capable of pursuing your goal.

Here are some indicators that a blocker-removal approach might be a good fit:

As I briefly discuss below, these might also indicate the presence of a level 3 issue.

Level 3: Necessity removal approaches

“Do I really need this to be okay?”

A client reports that they have been on several good dates recently. While none of them have led to anything romantic, the client has felt confident and enjoyed the occasions, and believes that the people they were seeing had a good time as well. They have several more dates lined up, and express confidence that they will find someone eventually. However, this trust in their eventual success does not change the crushing feelings of loneliness that they sometimes get when waking up in the morning.

An Internal Family Systems therapist might guide the client to get in contact with those feelings of loneliness and relate to them with compassion, making them more bearable as the client gives themselves some of the comfort they were looking for from the outside. After a while, they report that while they still want a partner, that desperate quality has softened.

A coherence therapist might help the client find an emotional learning that was formed when their father abandoned the family: “I’m defective and abandoned, and that’s why I end up alone”. This makes them equate being single with worthlessness. Exploring the issue, they find that the client also has a contradictory knowing: various single friends who are clearly valuable people. After bringing these beliefs together, the client no longer feels that their relationship status reflects their fundamental worth.

An existential therapist might ask the client what they are hoping to get out of the relationship. It turns out that the client is looking for validation of their worth as a person. They work together on alternative ways through which the client can affirm their own worth, such as creative projects, friendships, and expressing their values.

The necessity removal approach also assumes that you have some kind of cognitive or emotional issue. However, people focusing on this level typically think that you are not necessarily correct about what your biggest source of misery is.

They might hold that even if you did get into a relationship, that might still not fulfill some need that makes you feel so miserable without one. They might also point out that if you are desperate to get into a relationship and to stay in a relationship once you’ve found one, that might make you less attractive and more likely to accept abusive treatment. So, although you might still genuinely be happier in a relationship, it’s still better if you don’t feel like you’ll need one to be okay.

Sometimes, a necessity is also a blocker. For example, if someone strongly feels that they need a partner to be happy, the thought of trying and failing to find one can feel so painful that the person doesn’t even want to try. I think that blockers often form in the mind as an attempt to avoid some deeper pain that involves experiencing something as a necessity. Because of that, solving issues on level 3 tends to also solve them on level 2.

Here are some indicators that a necessity removal approach might be a good fit:

Level 4: Experiential acceptance approaches

“Can I be okay with not being okay?”

An Acceptance and Commitment therapist introduces the client to a metaphor of struggling in quicksand: “the more you fight the loneliness, the deeper you sink”. The therapist has the client try mindfulness exercises where the clienty observes their loneliness without trying to fix it: "I'm having the thought that I'll be alone forever. I notice tightness in my chest." The therapist then guides the client in identifying values other than avoiding loneliness. The client commits to acting in ways that are aligned with those values, regardless of whether or not they feel lonely.

When the client describes their fear of being alone forever, a somatic therapist asks, "Where do you feel that in your body?" The client describes a hollowness in their stomach. Rather than analyzing it, they simply stay present with the sensation. As they breathe and observe it, the sensation shifts, moves, and eventually dissipates.

A student at a vipassana meditation retreat meets a teacher and describes their fear of loneliness. The teacher guides them to note the components related to the experience: to mentally say “images” when there are mental images of always being alone, “tightness” when this makes the student’s chest feel tight, “breath” when the fear makes their breath go shallow. As the student does this, the sense of a solid and permanent feeling of loneliness turns into a stream of sensations that they can just let happen.

The experiential acceptance approach takes your problem to be the need to avoid feeling bad and miserable. Under this assumption, if feeling that way would be okay - maybe still something that you’d prefer to avoid if possible, but something that you could at least deal with - then you wouldn’t need to feel so stressed out.

People focusing on this level typically think that no matter how good your life gets, you’re still going to have pain and negative emotions. They might think that what causes suffering are not pain and negative emotions themselves, but the fact that you resist having pain and negative emotions. If you become capable of dropping that resistance, then you can deal with whatever life throws at you without it causing you suffering. This is famously summarized by Shinzen Young as “suffering = pain * resistance”.

Not only does the ability to willingly choose pain when it’s necessary enable you to further your values in ways that you otherwise couldn’t, pleasant things become even more enjoyable when you’re no longer afraid of losing them. You might not need to find a romantic partner, but you may still want to find one - and your relationships may be stronger and more enjoyable from that foundation.

Here are some indicators that a level 4 approach might be a good fit:

“You would like to just be okay with the problem” has both necessity removal (level 3) and experiential acceptance (level 4) versions. The necessity removal version of this is that you accept that the problem exists, and you’d like to face it without such extreme emotional pain. The experiential acceptance version is that you accept that the extreme emotional pain is going to happen, and you’d like to be okay with that. (This distinction is somewhat confusing because the experiential acceptance move may also make the necessity go away, but only if you’re not trying to make it go away - that wouldn’t be accepting it, after all.)

Some other examples level-ized

“I can’t deal with that.”

In the case of some problems, it is of course true that they may be impossible to entirely solve on one’s own. It is almost certainly true that you cannot fix global poverty by yourself, and that everyone will eventually die.

In those cases, the action-oriented approach takes a somewhat different form. There, action-oriented approaches are focused on at least making some difference. You may not ever solve global poverty, but maybe donating to an effective charity or doing direct work yourself will help at least one poor village, or slightly shift some of the structural causes of poverty. And even if nobody lives forever, you may be able to make sure that you or your loved ones don’t die needlessly early. In general, any approaches aimed at directly changing external circumstances, personal or systemic, fall under the action-oriented umbrella.

In the case of societal problems, a necessity removal does not deny that things like poverty are real problems - they are! Just as it does not deny that your life might be happier and more fulfilling with a partner than without. What it denies is that there is a direct connection between the world having problems and you needing to be constantly unhappy. It holds that it is possible for you to feel okay - happy, even - despite being fully aware of everything bad that happens in the world, and that this is a more sustainable foundation for doing good.

If the fact of people’s suffering makes you unable to properly rest or feel good about yourself, that is a recipe for burnout. It might also make you delude yourself into believing in overly simplistic solutions, if you cannot deal with the possibility that the problem might be genuinely too hard to solve in your lifetime. So even though the existence of global poverty is obviously bad, practitioners focused on necessity removal may tell you that it is better if you can learn to be okay with its existence and then act to reduce it.

Categorizing various approaches

Most modalities for improving your life operate across, or are potentially applicable to, multiple levels.

Level 1, action-oriented, is the domain of a lot of self-help, conventional coaching, and behavioral and solution-focused therapies. Various modalities, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, include a significant action-oriented component while also having other components. (ACT is somewhat difficult to place in this framework, because its action-oriented recommendations may not be about directly solving the initial problem the client presented with.[1])

Both level 2, blockers (“it’s impossible for me to find a relationship”), and level 3, necessities (“I have to be in a relationship”) are types of cognitive-emotional beliefs, so they can be potentially targeted by any therapy that works with those, either by reconsolidative or counteractive strategies. Psychodynamic approaches, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Coherence Therapy, Focusing-Oriented Psychotherapy, therapies based on parts work such as Internal Family Systems, etc, work on these.

At the same time, some therapies (such as CBT) tend to stay closer to the blocker level, while something like Coherence Therapy or Internal Family Systems encourages going toward the necessities level. This is in part because the necessities level tends closer to emotional than cognitive, and may be hard or impossible to access with interventions that operate purely cognitively.

Some therapies, such as Ideal Parent Figure protocol, specifically target the necessities level. Narrative therapy, which tends to examine broad beliefs such as culturally internalized stories about the necessity of having a partner, is typically also closest to necessity removal.

There are also various spiritual approaches, such as brahmavihara practices (of which metta or loving-kindness is the most well-known) and jhana practice that effectively act as necessity removal, by enabling the practitioner to experience feelings of happiness that are to some extent independent of external conditions. And some approaches, such as Solution-Focused Brief Therapy, that otherwise operate on the action-oriented level may also effectively act on the necessities level by, e.g., helping a person form strong friendships that take away some of the desperation to be in a relationship.

Level 4, experiential acceptance, is most strongly associated with spiritual and some philosophical schools such as Buddhism and Stoicism as well as various therapies influenced by them, such as mindfulness-based therapies, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, and Dialectical Behavior Therapy.

It is also touched upon therapies such as Internal Family Systems that encourage “unblending” (analogous to ACT’s “defusing”) from one’s difficult emotions and viewing them with empathy. Narrative therapy may also involve learning to hold space for multiple conflicting stories about one’s experience, rather than on avoiding negative feelings. Somatic therapies such as Somatic Experiencing typically work on levels 3-4.

Is there a “best” level?

From a personal benefit perspective, one might think that targeting the levels with the higher numbers is always better, as that lets you feel good regardless of your circumstances. And work on such levels may certainly have broader benefits than working on the lower-numbered ones.

But solving for the higher numbers may also be harder. In the personal domain, many people find it easier to go on dates and find a partner they click with than to shift their attachment patterns or to achieve perfect enlightenment and become liberated from all suffering. A person’s external circumstances may also actively prevent them from making any internal progress, such as if their obligations keep them stressed all the time, or if they are in an abusive environment that actively punishes them for getting better.

And unless you want to go fully renunciate, solving the highest-numbered levels still leaves all of the other levels to solve as well! For many problems, someone may need practical skills and trauma resolution and acceptance work.

On the other hand, from a social problem perspective, it’s easy to think that targeting the levels with lower numbers is better. You personally feeling better about yourself mostly does not help anyone else directly. But as previously mentioned, getting necessity removal or experiential acceptance in order may be a prerequisite for the ability to work on problems in the long-term, without falling victim to either burnout or overly optimistic thinking.

Many modalities also combine levels because it is easier to achieve results by operating on more than one level at once. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy gives a person tools for experiential acceptance and has them reflect on their values to take value-aligned actions in the real world. This is in part because accepting your painful feelings is a lot easier if that pain serves a greater purpose, in part because focusing on actions gives you something else to think about than just staring at your feelings all the time, and in part because fulfilling your values is what your life is supposed to be about. Or as the name of one ACT book puts it, the goal is to “get out of your head and into your life”.

The right level to target also depends on where exactly your problems lie. Some people need exactly the opposite advice as others. Some people report spending years in a toxic relationship or dating out of insecurity until they committed to doing inner work. Others report doing all kinds of inner work and then reducing their sadness by 99% by focusing on changing their environment instead. Sometimes the same person will endorse both inner work and external action for different problems - Kat Woods, who wrote the post on reducing her sadness by changing her environment, also wrote a post on how she eliminated her impostor syndrome with loving-kindness and confidence meditation.

The nature of your problems is also likely to change over time, or pursuing one level may shift the bottlenecks to another level. Someone might use a necessity removal approach to remove feelings of shame that previously made it difficult to spend time with people. This allows them to enjoy other people’s company more, and also to better take in the way that those other people appreciate them. This gives them evidence of their worth that allows for deeper reconsolidation, which then leads to losing more social anxiety, and so on.

A good rule of thumb might be: experiment with different approaches, keep doing the things that work for you, and once those run into diminishing returns, try things on other levels than the one you’ve been focused on. And don’t forget to also look after your nutrition, exercise, sleep, etc. - those also have a huge effect on your well-being and emotional state.

Thanks to @Chris Lakin for conversations that led to the writing of this post.

Advertisement 1: If you sometimes have emotional problems, I help people having them in exchange for money. I have the most training and experience in Internal Family Systems therapy, so I tend to focus the heaviest on the blocker and necessity removal levels, though I can also dip into the other ones. Note that I don’t feel qualified to take clients suffering from serious mental health issues or extremely challenging external circumstances.

Advertisement 2: This article was first published as a paid piece on my Substack one week ago. Most of my content becomes free eventually, but if you'd like me to write more often and to see my writing earlier, consider getting a subscription! If I get enough subscribers, I may be able to write much more regularly than I've done before.

ACT might say something like: "Okay, you're suffering about being single. Let's identify your core values - maybe creativity, community service, or personal growth - and commit to taking concrete actions aligned with those values, regardless of your relationship status". ACT’s theory is that living according to your values will reduce psychological suffering and create a more fulfilling life. This might also end up helping with dating, but it’s not the primary goal.