This is a linkpost from ClearerThinking.org. We've included some excerpts of the article below, but you can see the full post here.

A libertarian, a socialist, an environmentalist, and a pro-development YIMBY watch an apartment complex being built. The libertarian is pleased - "the hand of the market at work!" - whereas the socialist worries that the building is a harbinger of gentrification; the YIMBY sees progress, but the environmentalist is concerned about the building’s carbon footprint. They’re all seeing the same thing, but they understand it differently, because they inhabit different worldviews.

We can think of worldviews as snow globes. We each occupy our own snow globe and, when we’re inside it, it can seem like the whole world. If it’s snowing in our snow globe, we think it’s snowing everywhere; if our snow globe is made of green glass, everything looks green to us. We might not even realize that there’s anything beyond our snow globe! But if we can step outside, we see that our view from inside was only part of a much larger picture. If you can step outside your snow globe - and visit other people’s - you’ll be able to see a more accurate representation of the world and communicate better with others. For every snow globe you master, you’ll gain a powerful new lens through which to see the world - and you’ll see that no single snow globe has all the answers.

Image generated using the AI DALL•E 2

What makes a worldview?

Worldviews are a type of story we learn about how the world works and about what things matter and why. In this post, we put forward a theory of worldviews that will help you understand how different worldviews work. We call this "Snow Globe Theory." Every worldview includes many beliefs, but after reflecting on a wide variety of worldviews, we believe that almost every one has four central components. There are other common elements that some worldviews have but others don’t - for example, a strong culture, or a theory about trustworthy sources of knowledge – but this article will focus on these four central elements:

What is good?

Where do good and bad come from?

Who deserves the good?

How can you do good or be good?

You can understand a worldview quite well if you know what thoughtful people with that worldview would all answer in response to these four questions. While each individual member of a group will have somewhat different answers to the questions above, it is the portions of their answers that most members of that group share with each other that compose the group's worldview. Our article explains these four components in more detail, along with other factors that can contribute to worldviews.

Why it's important to understand how people think through the theory of worldviews

The truth lies outside any one worldview

Most of us are taught a worldview growing up, or we pick up one in college or from media that we consume. It can be tempting to stay in that snow globe forever. However, being stuck in just one worldview limits our ability to see the world as it truly is. Worldviews tend to be simplistic, which has some advantages - it’s easier to understand the world and relate to other people if you share simple stories about good and bad, right and wrong. But because worldviews are simple, and the world is complex, any one worldview necessarily misses a lot of nuance. Just about every worldview has some truths that it is good at seeing accurately, and some truths that it is systematically blind to. But you don't have to be stuck in just one worldview. The more worldviews you understand, the more accurately you'll see the world.

Occupying many snow globes lets you better understand the world and communicate more effectively

You might think, "Ok, but I know that my worldview is correct - otherwise, it wouldn’t be my worldview! Why should I waste my time understanding people whose beliefs are flawed or toxic?" For instance, if you’re strongly committed to one of the progressive worldviews, you might not see the value in understanding the point of view of one of the conservative worldviews, and vice versa. However, it’s useful to know how other people think even if you believe that their worldview is deeply wrong. Governments, corporations, non-profits, religions, political parties, and other powerful groups are often guided by a particular worldview. If you don’t understand that worldview, then you’ll be unable to predict what these groups will do. You will also struggle to communicate with them in a way that they care about, or persuade them to do things differently. When people engage with others who have a different worldview, they frequently make the mistake of relying too much on the stories and assumptions of their own worldview. But this is unlikely to work well, because the person they are talking to does not share these assumptions. To be really convincing to one another, you have to be able to see things from their perspective. To give a topical example: in abortion debates, pro-choice progressives often misunderstand the worldview of pro-life conservatives. We’re publishing this article only a few days after Roe v Wade was overturned; since then, abortion has been banned or restricted in several U.S. states.

We originally drafted this section before the overturning, and know that some of our readers will be feeling immense grief or distress at this ruling, and that abortion is an exceptionally fraught and emotionally-charged issue at the best of times. No matter how much you believe that the overturning of Roe v. Wade was harmful and wrong, and even if your only goal is to win a political victory, we believe it’s still going to be useful to understand what pro-lifers really think: that way, you’ll be better placed to predict what they’ll do, or persuade them of your own point of view.

When talking about abortion, progressives sometimes say things like this tweet by @leilacohan which has been retweeted more than one hundred thousand times:

"If it was about babies, we’d have excellent and free universal maternal care. You wouldn’t be charged a cent to give birth, no matter how complicated your delivery was. If it was about babies, we’d have months and months of parental leave, for everyone.

If it was about babies, we’d have free lactation consultants, free diapers, free formula. If it was about babies, we’d have free and excellent childcare from newborns on. If it was about babies, we’d have universal preschool and pre-k and guaranteed after school placements."

From a progressive worldview, this tweet is powerful and persuasive; but it’s unlikely to be persuasive to U.S.-based Christian conservative pro-lifers - the group that it’s apparently discussing - because it misunderstands their worldview. The argument is that if conservatives cared about babies, they would support babies and children through funding and social programs. The subtext is that since conservatives don’t support those things, they are being dishonest about what they care about, and just pretending that they care about not letting fetuses die. But the idea that we should try to make good things happen through government intervention is itself a progressive belief. Conservatives tend to think that individual responsibility is more important, and to be skeptical that large government-run social programs produce good outcomes. While modern Christians have a variety of views on abortion (depending on factors such as their denomination), and the Bible doesn't address the topic directly, within the first few hundred years of Christianity there were Christian scholars arguing that life begins at conception (rather than birth). In the U.S., many Christian conservatives who oppose abortion believe that fetuses should have the same rights as born babies: we polled 49 people in the US who say that they’re "very happy" that Roe v Wade has been overturned. Of these, 90% said that they think abortion is wrong because it’s murder (i.e., similar to killing an adult human).

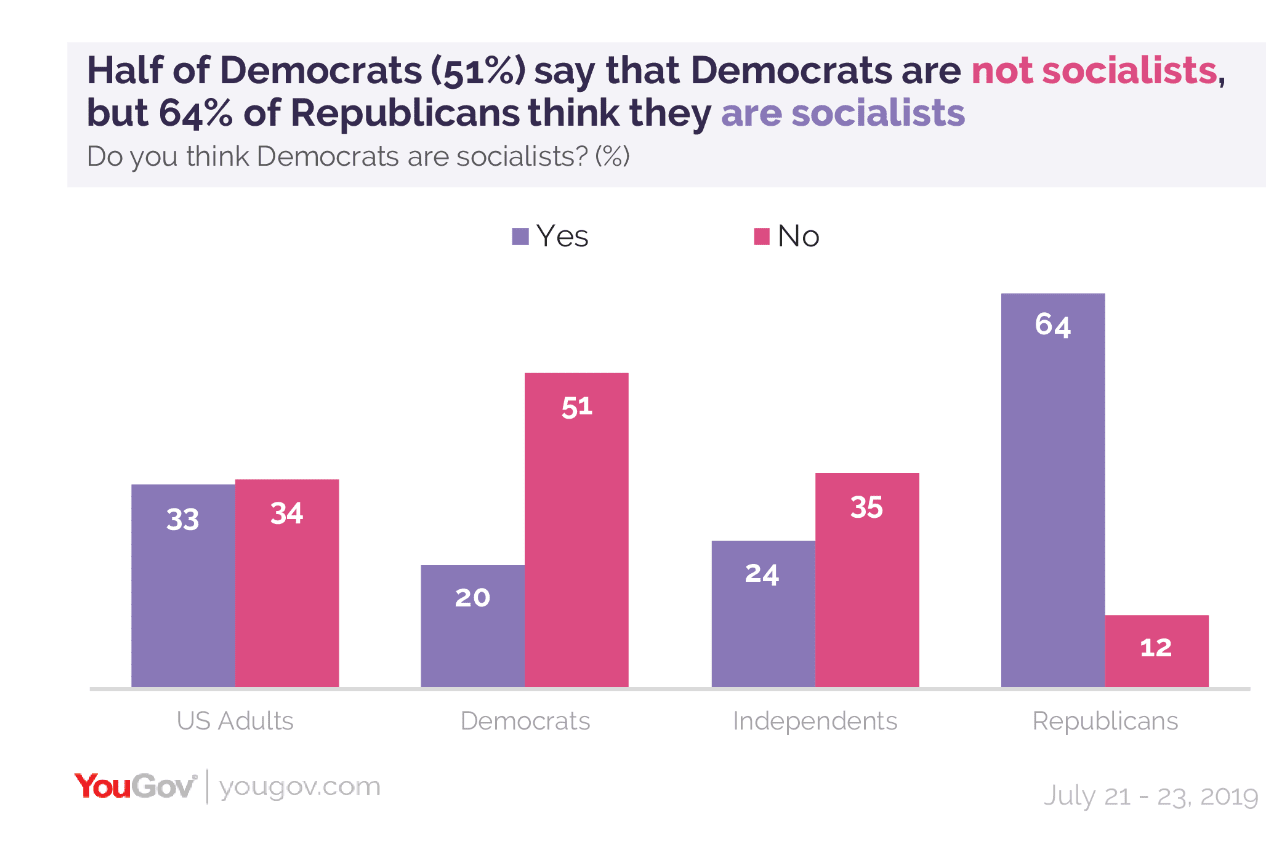

From within a U.S. Christian conservative worldview, there is no tension between (1) thinking that abortion is murder and (2) not supporting free diapers and childcare. If you momentarily step inside the snowglobe of this worldview, it becomes clear that you can oppose what you see as murder without believing that the government should fund large programs aimed at improving people’s quality of life. Another common misunderstanding (from the other side of the political spectrum) is that conservatives sometimes label anyone left-of-center as a "socialist," and believe that liberals oppose capitalism (see the chart below which demonstrates the misunderstanding). But this is a misunderstanding of the average liberal’s worldview: in the U.S., most self-identified liberals (for example, Democrat voters) aren’t "socialists" in the sense of "people who want to abolish capitalism and private ownership." Most support capitalism, but they differ from conservatives in that they support an expanded social safety net and favor moderate wealth redistribution through progressive tax policies.

This is just an excerpt from our article on ClearerThinking.org. You can use this link if you'd like to read the entire piece.