It's very easy for analytical people to notice problems and find things to complain about. But it's important to figure out: is the thing you're complaining about a 1/10 issue or a 6/10? There's no such thing as a perfect environment, and if you are constantly complaining about 2/10 issues, that's actually a good thing—it means there are no more substantive issues, otherwise you'd be focused on them. I personally don't allow myself to get bothered by anything less than a 4/10.

Resolving 3/10 issues that you can resolve in five minutes is very valuable. With my old PC, I was switching manually to the speakers that I preferred. Sometimes this meant that applications like switched to some default "for communication" speakers. I wouldn't rate it higher than 3/10 as switching speakers on zoom is not that big of a deal.

On the other hand, really looking through the Windows speaker settings, removing "speakers" that are just audio out of various devices and setting the proper defaults took me less than five minutes. I didn't know beforehand that these default existed so, I didn't know that the problem was solvable in five minutes.

Simply asking ChatGPT whether there's an easy solution to your <4/10 problems can be very useful.

I would assume that this would not be categorised as “complaining”. Sure, if something is 2/10 bothering you and there is an easy way to fix it, then it is worth fixing, but I would assume that “being bothered” in that context means “entering the state of dissatisfaction with current affairs”.

If we take the example of my speaker recognition, I didn't know that there was an easy way to fix it. It turned out to be fixable in five minutes but that's not something I knew beforehand. I certainly did complain to other people when I computer put in speaker I didn't like.

I think there are plenty of problems that people have where there's not a solution that they can think of in five seconds but where spending five minutes of focused attention or these days just asking an LLM, can make a lot of progress on the issue.

It doesn't matter if you want to dance at your friend's wedding; if you think the wedding would be "better" if more people danced, and you dancing would meaningfully contribute to others being more likely to dance, you should be dancing. You should incorporate the positive externality of the social contagion effect of your actions for most things you do (eg if should you drink alcohol, bike, use Twitter etc.).

Yes! I wish more people adopted FDT/UDT style decision theory. We already (to some extent, and not deliberately) borrow wisdom from timeless decision theories (i.e. “treat others like you would like them to treat you”, “if everybody thought like that the world would be on fire” etc.), but not for the small scale low stakes social situations, and this exactly the point you bring here.

No matter how mediocre your year is or how much you are floundering, when you are 70, 80, 90 etc. years old, you will wish so badly you could be back in your situation today. I'm not saying your current situation is better than you think, but being older is probably much worse than you think, so cherish the lack of oldness now.

True and horrific. Everyone underestimates the badness of aging.

Many arguments aren't actually about facts but about unspoken values or assumptions about how the world works.

This reminds me of John Nerst's 2018 post 30 Fundamentals:

It would be helpful if people writing online could point to some description of their fundamental beliefs, interests and assumptions, so you could get a better picture of who they are and where their writing is coming from [2].

I’ve tried to do this below. I wrote down my fundamentals, my main beliefs, my intellectual background scenery. They are all things that inform what I write, are relevant to how I interpret other texts, and help others interpret my writing.

I’d like to encourage other bloggers and writers to do this too. It’s a great tool, not just for others but for yourself too. Have one you can link to so people can sniff you out and get a feel. But be warned, enumerating your own unstated basic beliefs was much harder than I thought it’d be. It’s a chasing-your-tail type enterprise that’ll leave you unsatisfied. I thought I’d have 10 or 12 points but now there’s 30 because I kept coming up with more. The list of background things people can differ on without necessarily realizing it seems infinitely long, and knowing whether to include something or take it for granted doesn’t get any easier just because you’re writing specifically to solve that problem one level above. There are assumptions behind assumptions behind assumptions.

(As an aside, Nerst's exercise might be useful for personalising LLM system prompts too.)

That said, I'm a bit skeptical of the tractability of this approach to resolve deep disagreements between smart knowledgeable well-intentioned people, mostly because my experience has resonated with what Scott wrote about "high-level generators of disagreements" wrote in Varieties of Argumentative Experience:

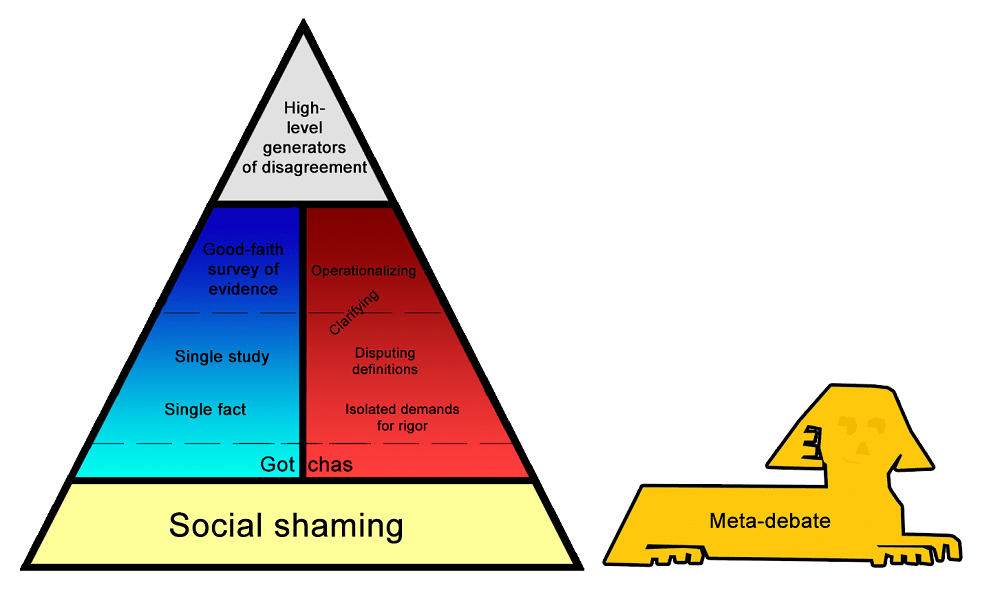

If we were to classify disagreements themselves – talk about what people are doing when they’re even having an argument – I think it would look something like this:

Most people are either meta-debating – debating whether some parties in the debate are violating norms – or they’re just shaming, trying to push one side of the debate outside the bounds of respectability.

If you can get past that level, you end up discussing facts (blue column on the left) and/or philosophizing about how the argument has to fit together before one side is “right” or “wrong” (red column on the right). Either of these can be anywhere from throwing out a one-line claim and adding “Checkmate, atheists” at the end of it, to cooperating with the other person to try to figure out exactly what considerations are relevant and which sources best resolve them.

If you can get past that level, you run into really high-level disagreements about overall moral systems, or which goods are more valuable than others, or what “freedom” means, or stuff like that. These are basically unresolvable with anything less than a lifetime of philosophical work, but they usually allow mutual understanding and respect.

Bit more on those generators:

High-level generators of disagreement are what remains when everyone understands exactly what’s being argued, and agrees on what all the evidence says, but have vague and hard-to-define reasons for disagreeing anyway. In retrospect, these are probably why the disagreement arose in the first place, with a lot of the more specific points being downstream of them and kind of made-up justifications. These are almost impossible to resolve even in principle. ...

Some of these involve what social signal an action might send; for example, even a just war might have the subtle effect of legitimizing war in people’s minds. Others involve cases where we expect our information to be biased or our analysis to be inaccurate; for example, if past regulations that seemed good have gone wrong, we might expect the next one to go wrong even if we can’t think of arguments against it. Others involve differences in very vague and long-term predictions, like whether it’s reasonable to worry about the government descending into tyranny or anarchy. Others involve fundamentally different moral systems, like if it’s okay to kill someone for a greater good. And the most frustrating involve chaotic and uncomputable situations that have to be solved by metis or phronesis or similar-sounding Greek words, where different people’s Greek words give them different opinions.

You can always try debating these points further. But these sorts of high-level generators are usually formed from hundreds of different cases and can’t easily be simplified or disproven. Maybe the best you can do is share the situations that led to you having the generators you do. Sometimes good art can help.

The high-level generators of disagreement can sound a lot like really bad and stupid arguments from previous levels. “We just have fundamentally different values” can sound a lot like “You’re just an evil person”. “I’ve got a heuristic here based on a lot of other cases I’ve seen” can sound a lot like “I prefer anecdotal evidence to facts”. And “I don’t think we can trust explicit reasoning in an area as fraught as this” can sound a lot like “I hate logic and am going to do whatever my biases say”. If there’s a difference, I think it comes from having gone through all the previous steps – having confirmed that the other person knows as much as you might be intellectual equals who are both equally concerned about doing the moral thing – and realizing that both of you alike are controlled by high-level generators. High-level generators aren’t biases in the sense of mistakes. They’re the strategies everyone uses to guide themselves in uncertain situations.

If you don’t feel like what you are doing now is already in some sense “great”, you likely will not be great. You've got to really believe and lean into what you are doing. Be more ambitious and daring in your work.

I sort of agree with this, but assuming it's true, the following sentence seems like a non-sequitur. If the seeds of greatness aren't already there, why would it help to "lean into" anything? Why would being more ambitious or daring help? Those help grow seeds, not create them.

I think a big part of "greatness" is the self-confidence to feel comfortable doing the thing that you think is best.

In my opinion, the two best musical talent spotters of modern times are Miles Davis and Col. Bruce Hampton.

Miles was the biggest name in jazz, so most young musicians wanted to work with him.

Col. Bruce Hampton was not a huge name and couldn't offer conventional opportunity, yet he helped launch the careers of musicians like Jimmy Herring, Oteil Burbridge, Kofi Burbridge, Jeff Sipe, Kevin Scott, etc. When you read about Bruce (which I recommend everyone does, one of the most fascinating people of all time!), it seems clear these people had the potential, but Bruce gave them the confidence and courage to really be themselves and to pursue their wildest creative visions. While not everyone can be "great," I believe there are many more people with the potential for greatness, and one of the biggest blockers to them achieving this is not feeling comfortable enough to truly pursue their own thing and go for it.

These are the most significant pieces of life advice/wisdom that have benefited me, that others often don't think about and I end up sharing very frequently.

I wanted to share this here for a few reasons: First and most important, I think many people here will find this interesting and beneficial. I am very proud of this post and the feedback so far is that others seem to find it extremely valuable.

Second, writing this post has been my favourite writing experience ever. Writing a post of your most essential and frequently recommended life wisdom—as this one is for me—feels like my entire soul and personality are captured within it. Given how much I enjoyed doing this, I want to share this as a gentle nudge to others: I hope you consider writing such a post for yourself. Both because we will all be better off if more people write such posts, sharing new pieces of great advice and heuristics, but also because I think it's good to have fun and I think you will have a lot of fun writing it.

Often the smartest/best people succeed by employing the simplest models most effectively, and truly, truly grasping and understanding their implications.

[“I'll make a comment about that. It's funny that I think the most important thing to do on data analysis is to do the simple things right. So, here's a kind of non-secret about what we did at renaissance: in my opinion, our most important statistical tool was simple regression with one target and one independent variable. It's the simplest statistical model you can imagine. Any reasonably smart high school student could do it. Now we have some of the smartest people around, working in our hedge fund, we have string theorists we recruited from Harvard, and they're doing simple regression. Is this stupid and pointless? Should we be hiring stupider people and paying them less? And the answer is no. And the reason is nobody tells you what the variables you should be regressing [are]. What's the target. Should you do a nonlinear transform before you regress? What's the source? Should you clean your data? Do you notice when your results are obviously rubbish? And so on. And the smarter you are the less likely you are to make a stupid mistake. And that's why I think you often need smart people who appear to be doing something technically very easy, but actually usually not so easy. - Nick Patterson”](*)