As a datapoint, I tested positive on 3 antigen tests of two different kinds and negative on a Cue test in the same hour, on my first day of having COVID. My suspicion is that this was because I swabbed my throat for the antigen tests, but not for the Cue test because I wasn't sure if saliva worked for Cue. As further supporting evidence, I lightly brushed my throat for antigen test #1 and got an extremely faint line, and then vigorously swabbed it less an than hour later and got a very clear dark line (both on BinaxNow tests).

Edit: These tests were all performed yesterday, May 2 2022.

Have you read anything lately on whether throat swabs are a reliable procedure for antigen tests that aren't officially indicated for throat swabs? Back when I looked into this in December it seemed like there were concerns about false positives (though the only study I found from a quick search was one which literally used drinks - soda, if I recall correctly - as buffer - https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971221006548), and public health authorities / experts are still not officially recommending that (for whatever that is worth...).

And...sorry to hear you might (probably?) have COVID!

Let me give you two answers for the price of one:

-

FDA and others have been very clear about this: you should use the tests as directed.

-

I (a decades-long amateur epidemiologist who's done a deep dive on antigen test research), my partner (a medical epidemiologist who works full-time on Covid), and several other epidemiologists I'm aware of, all use throat + nasal swabs.

I wouldn't worry at all about false positives: they really haven't been an issue with antigen tests. If I got a positive from a throat + nasal swab, I'd follow it up with a nasal-only swab or a PCR, just to be sure.

There is non-zero risk that you'd get false negatives, by some unknown mechanism. That seems unlikely given that some countries like the UK use throat swabs, but it's possible. It's my well-informed but not data-supported belief that the benefit of swabbing your throat probably exceeds the downside.

I haven't looked into this, no. I'm quite confident that I have COVID; I have all the classic symptoms (fever, cough, shortness of breath). I also re-tested using an antigen test today with a nasal-only swab and got a positive.

I'm wondering if you can explain a bit more about your thinking here.

From my perspective, there's a strong prior that antigen tests work well for Covid screening:

-

There are numerous peer-reviewed studies to that effect. Here are two recent ones, but there are many others Soni et. al., Jüni et. al..

-

Multiple experts in the field continue to assert that antigen tests work very well for Covid screening. Michael Mina is extremely knowledgeable on this topic and particularly vocal about it.

It's important to note here that PCR / antigen discordance early in an infection is not evidence that antigen tests aren't working. Because antigen tests are less sensitive than PCR, they are good at detecting people who are infectious, but not people who are infected but not infectious. Mina has an excellent explanation of why symptoms often start several days before people become infectious.

This post presents new data, which is interesting (especially from a perspective of real-world failure scenarios), but this is weak data: it isn't peer reviewed, there's no study protocol, and the results are inconsistent.

It seems to me the correct interpretation is to update slightly in the direction of antigen tests working less well than previously believed, but to continue to believe they are useful and effective (but far from perfect). Am I missing something?

The Soni study shows only 20% of cases were antigen positive the same day they became PCR positive (and because they were sampled only every 48 hours, the actual power is less still). The second showed that antigen tests didn't begin to pick go positive until 2 days after the positive PCR test.

So I don't see how these contradict me.

I don't have high expectations for people marketing themselves as covid experts. Maybe this particular guy is good, which would be great for me because doing this research myself is time consuming. What makes you value this guy in particular?

There is a more complicated argument that the genetic tests are picking up infected but uninfectious people. That's certainly possible. I've got my stack of anecdotes about people who caught covid from someone with no or ambiguous symptoms and multiple negative tests, but those don't have a denominator either. However given the primate challenge data that current vaccines don't affect nasal viral titers or immune response (even while they're providing lots of protection to the throat and lungs), I'm confused by this.

This particular data is for INO-4800, but unless something very weird is happening the same principle would apply to the intramuscular mRNA vaccines.

It seems to me the correct interpretation is to update slightly in the direction of antigen tests working less well than previously believed, but to continue to believe they are useful and effective (but far from perfect). Am I missing something?

Depends what your starting position was. I'm arguing against treating antigen tests as near-100% screening that removes the need for other safety measures, which seems to be the attitude of the party hosts I'm seeing. If you already viewed them as "better than nothing but not by much", I don't think you need to change at all.

Why do I respect Michael Mina? Weak but deep answer: because in my experience he’s been consistently smart, and insightful about Covid and especially about testing (and he’s a professional epidemiologist / immunologist). Strong but shallow answer: because my partner, who is a medical epidemiologist working full-time on Covid, thinks highly of him.

If you’re not already familiar with her, you might also be interested in Katelyn Jetelina (Your Local Epidemiologist). IMHO, she produces by far the best deep research summaries for laypeople. Here’s a recent piece of hers on antigen tests.

In the interest of staying focused on truth-finding, here’s my understanding of the crux of our disagreement—does this look right to you?

I believe that using antigen tests before social gatherings substantially reduces the amount of transmission at those gatherings. It’s very hard to put a number on this—if I had to guess, I’d say a 70% reduction, but probably somewhere between 25% and 90%. If I’m understanding you correctly, you'd pick a very low number: less than 10%?

Let me try to explain my thinking, which I believe reflects the current medical / scientific consensus (though I think most scientists would balk at the rationalist proclivity for picking best-guess numbers).

There’s a massive body of evidence that antigen tests can detect all strains of Covid, including Omicron. Antigen tests are much less sensitive than PCR tests, meaning that they will consistently return false negatives when viral levels are low, but they have excellent sensitivity when viral levels are high.

The standard interpretation of that data is that antigen tests are an unreliable way to tell if you have Covid early on in an infection, but they are quite good at detecting Covid when viral levels are high (and therefore when you’re infectious).

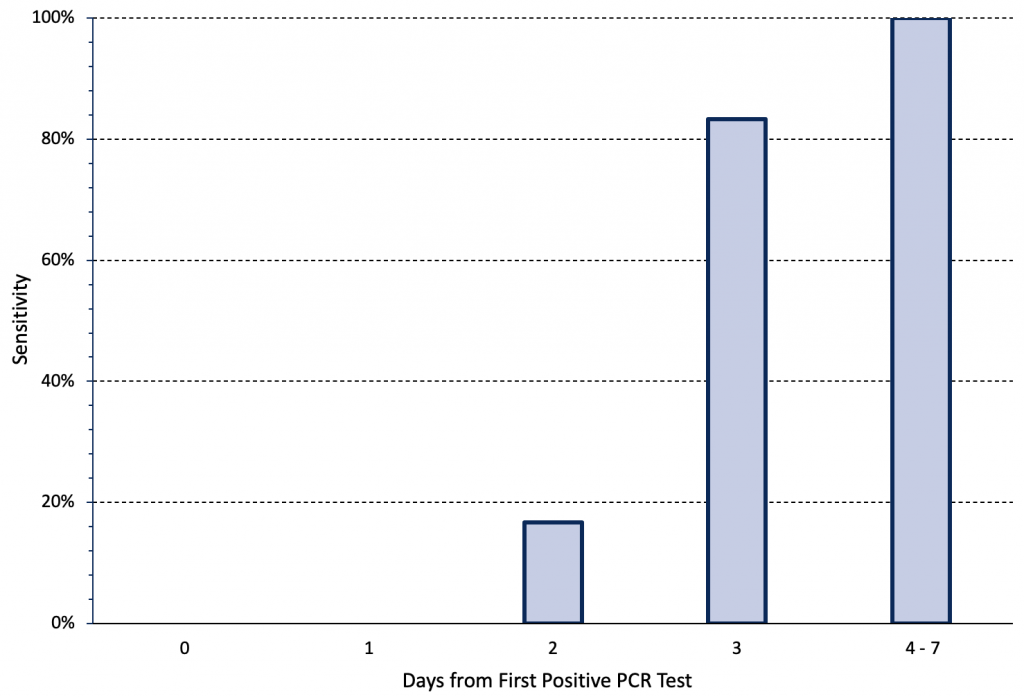

The Soni et. al. chart you included is an example of this in action. Antigen tests gave nearly universal false negatives during the first two days that PCR tests were positive. Viral levels (and therefore infectiousness) tend to be low during the first couple of days, especially among vaccinated people (which most of the Soni subjects were). So what we’re seeing there is that antigen tests would consistently have missed people early in their infections, when they were minimally infectious.

From day 3 onward, however, antigen tests were extremely accurate. This corresponds to them consistently detecting people during their period of maximum infectiousness.

So there’s a huge amount of evidence that antigen tests are highly sensitive during periods of peak viral load / infectiousness. That’s easy to measure, and I think it’s pretty definitively established at this point. The question we’re really asking, however, is how that affects infectiousness. Unfortunately, there’s no really clear way to answer that.

We believe most transmission happens during periods of high viral load, and we know antigen tests are very accurate during that time. But we don’t know exactly how viral levels impact transmission, and figuring that out would require complex, expensive studies that would likely not be approved for ethical reasons.

I think my current expectation of risk reduction from antigen tests is more like 20-60% than <10%, but I'll also note that it matters a lot what your population is. In Elizabeth's social circle my guess is that most people aren't coming to parties if they've had any suspected positive contact, have any weak symptoms, etc, such that there's a strong selection effect screening out the clearly-positive people. (Or like, imagine everyone with these risk factors takes an antigen test anyways—then requiring tests doesn't add anything.)

I haven't read this whole thread but for the record, I often agree with Michael Mina and think he does great original thinking about these topics, yet think in this case he's just wrong with his extremely high estimates of antigen test sensitivity during contagion. I think his model on antigen tests specifically is theoretically great and a good extrapolation from a few decent assumptions, but just doesn't match what we see on the ground.

For example, I've written before about how even PCRs seem to have 5-10% FNR in the hospitalized, and how PCR tests look even worse from anecdata. Antigen tests get baselined against PCR so will be at least this bad.

We also see things like a clinical trial on QuickVue tests that shows only ~83% sensitivity. Admittedly other studies of antigen tests show ~98% sensitivity, but I think publication bias and results-desirability bias here means that if the clinical trial only shows 83%, then that's decent evidence that studies finding higher are a bit flawed. I would not have guess they could get to 98% though so there's something that doesn't make sense here.

I know the standard heuristic is to trust scientific findings over anecdata, but I think in this case that should be reversed if you're extremely scientifically literate and closely tracking things on the ground. Knowing all the things that can go wrong with even very careful scientific findings, I just don't trust these studies claiming very high sensitivity much—I think they also contradict FDA data on Cue tests, data/anecdata about nasal+saliva tests working better than just nasal, etc.

(Maybe I'm preaching to the choir and you know most of this, given your range was 25-90%. But I guess I see pretty good evidence it can't possibly be at the high end of that range.)

That all makes complete sense.

And yes, the specifics of the population make a huge difference. Honestly, I think that accounts for the breadth of my estimate range more than uncertainty about abstract test performance does.

Apologies for poor formatting, I'm on mobile.

It looks to me like the first study Jetelina cites agreed with me? Average time to positive antigen test was 3 days after positive PCR. Everyone developed symptoms within 2 days of the positive PCR (which is surprising in and of itself), and at least 4/30 people spread covid before getting a positive antigen test, which presumably would have been higher if they didn't have the PCR to warn them. PCR is more sensitive than cue tests so this doesn't translate directly, but I consider it to bolster the case against preemptive antigen testing being useful.

In the second study, which was on demand not preemptive testing, antigen tests detected 50% of PCR positives. If I understand your claim correctly, it's that the PCR+/antigen- people aren't very contagious? I agree that antigen+ people are on average more contagious, but since symptomatic people (should) stay home, I don't think that's the right reference class. The meaningful work is done identifying people who couldn't otherwise be identified as infectious.

I think it's important to emphasize that antigen+ people are much more contagious than antigen-. It's hard to quantify that, but based on typical differences in Ct value, it's probably a very substantial difference (factor of 10+?).

You're absolutely right that the reference class is the key issue (if there's one thing I've learned from hanging out with epidemiologists, it's that they're always grumpy about people using the wrong denominator).

In a perfect world, where everyone with any symptoms whatsoever stayed home and was scrupulous about following what the CDC exit guidance ought to be, antigen tests would be significantly less useful. But in the real world, people absolutely go out when they have mild symptoms. That's advocated for in the comments right below this, which are from people who are presumably much more conscientious than average.

IMHO, the biggest value of antigen tests is in catching people who are mildly symptomatic but think it's just allergies / they had a negative test last week so it can't be covid / they're probably over the worst of it. Within my (not enormous) extended social circle, I'm aware of two very recent cases when antigen tests flagged as infectious people who would otherwise have been out and about despite having mild symptoms.

symptomatic people (should) stay home

This is kind of OT, but I'm going to ask anyway: under what conditions do you think that symptomatic people should stay home? If a person's symptoms are debilitating, staying home is the obviously correct choice. But if a person's symptoms aren't debilitating and wears a ventless respirator (and can tolerate it and it doesn't interfere too much in what they're doing), I don't see why they should stay home.

In general I think people who are definitely sick should not go to parties or the social part of work (which for almost everyone I know is the part that can't be done from home), even with ventless respirators, even with a negative covid test. There are lots of diseases, spreading them is costly, masks interfere too much at parties and in person interactions at work, which is the only reason for many people to go (if you're at a job that benefits from in-person presence because of equipment or because your home is too disruptive, this doesn't apply. if your job involves interacting with a lot of people, or food, obviously don't go while symptomatic). I think running unpostponable maintenance tasks like grocery shopping (if you can't get delivery) or doctors visits is okay.

The problem I find harder is people who are mildly symptomatic, in ways that could be an illness or allergies, or are on the trail end up symptoms after a disease has probably but not definitely been cleared. "No interaction for five days after a sniffly nose" is life ruining for a lot of people.

The problem I find harder is people who are mildly symptomatic, in ways that could be an illness or allergies, or are on the trail end up symptoms after a disease has probably but not definitely been cleared. "No interaction for five days after a sniffly nose" is life ruining for a lot of people.

Yeah, this is a much more difficult situation for me. I think I more or less always have minor COVID symptoms if construed strictly, given that various minor allergies or similar have the same symptoms as COVID...

Decreased social interaction can be a showstopper but sometimes it isn't; so, I think a case-by-case policy would be more reasonable than a general stay-at-home-no-matter-what recommendation. In the party scenario, the choice is between attending and not attending (I'm assuming that there's no remote party option like VR chat or something). For some parties (like birthday parties), attending might be better even if social interaction is reduced. For others (like indoor dinner parties), it might not be worth attending. In the job scenario, many jobs can't be performed remotely, so physically attending would be better. You seem to have acknowledged this when you said:

if you're at a job that benefits from in-person presence because of equipment or because your home is too disruptive, this doesn't apply

Epistemic status: I strongly believe this is the right conclusion given the available data. The best available data is not that good, and if better data comes out I reserve the right to change my opinion.

EDIT (4/27): In a development I consider deeply frustrating but probably ultimately good, the same office is now getting much more useful information from antigen tests. They aren’t tracking with same rigor so I can’t comapre results, but they are now beating the bar of “literally ever noticing covid”.

In an attempt to avoid covid without being miserable, many of my friends are hosting group events but requiring attendees to take a home covid test beforehand. Based on data from a medium-sized office, I believe testing for covid with the tests people are using, to be security theater and provide no decrease in risk. Antigen tests don’t work for covid screening. There is a more expensive home test available that provides some value, and rapid PCR may still be viable.

It’s important to distinguish between test types here: antigen tests look for viral proteins, and genetic amplification tests amplify viral RNA until it reaches detectable levels. The latter are much more sensitive. Most home tests are antigen tests, with the exception of Cue, which uses NAAT (a type of genetic amplification). An office in the bay area used aggressive testing with both Cue and antigen tests to control covid in the office and kept meticulous notes, which they were kind enough to share with me. Here are the aggregated numbers:

A common defense of antigen tests is that they detect whether you’re contagious at that moment, not whether you will eventually become contagious. Given the existence of people who tested antigen-negative while Cue-positive and symptomatic, I can’t take that seriously.

Unfortunately Cue tests are very expensive. You need a dedicated reader, which is $250, and tests are $65 each (some discount if you sign up for a subscription). A reader can only run 1 test at a time and each test takes 30 minutes, so you need a lot for large gatherings even if people stagger their entrances.

My contact’s best guess is that the aggressive testing reduced but did not eliminate in-office spread, but it’s hard to quantify because any given case could have been caught outside the office, and because they were trying so many interventions at once. Multiple people tested positive, took a second test right away, and got a negative result, some of whom went on to develop symptoms; we should probably assume the same chance of someone testing negative when a second test would have come back positive, and some of those would have been true positives. So even extremely aggressive testing has gaps.

Meanwhile, have I mentioned lately how good open windows and air purifiers are for covid? And other illnesses, and pollution? And that taping a HEPA filter to a box fan is a reasonable substitute for an air purifier achievable for a very small number of dollars? Have you changed your filter recently?

PS. Before you throw your antigen tests out, note that they are more useful than Cue tests for determining if you’re over covid. Like PCR, NAAT can continue to pick up dead RNA for days, maybe weeks, after you have cleared the infection. A negative antigen test after symptoms have abated and there has been at least one positive test is still useful evidence to me.

PPS. I went through some notes and back in September I estimated that antigen testing would catch 25-70% of presymptomatic covid cases. Omicron moves faster, maybe faster enough that 25% was reasonable for delta, but 70% looks obviously too high now.

PPPS. Talked to another person at the office, their take is the Cue tests are oversensitive. I think this fits the data worse but feel obliged to pass it on since they were there and I wasn’t.

PPPPS (5/02): multiple people responded across platforms that they had gotten positive antigen tests. One or two of these was even presymptomatic. I acknowledge the existence proof but will not be updating until the data has a denominator. If you’re doing a large event like a conference I encourage you to give everyone both cue, antigen, and rapid PCR tests and record their results, and who eventually gets sick. If you’d like help designing this experiment in more detail please reach out (elizabeth-at-acesounderglass.com)