I'm pretty excited about Transluce's agenda in general, and I'm glad to see it written up! Making progress on the various oversight and interpretability problems listed here should make it much easier to surface undesirable behaviors in modern-day AIs (which I agree we already need superhuman-ish supervision over).

There are three areas I'd love to see developed further.

The first is how to train oversight AIs when the oversight tasks are no longer easily verifiable—for example, sophisticated reward hacks that can fool expert coders, or hard-to-verify sandbagging behavior on safety-related research. You mentioned that this would get covered in the next post, so I'm looking forward to that.

The second is how robust these oversight mechanisms are to optimization. It seems like a bad idea to train directly against unwanted concepts in predictive concept decoders, but maybe training directly against investigator agents for unwanted behaviors is fine? Using Docent to surface issues in RL environments (and then fixing those issues) also seems good? In some cases, if we have good interpretability, we can actually understand where the undesirable behaviors come from (i.e., data attribution) and address the source of the problem. That's great!

But I don't think this would always be the case even if we have way better versions of existing tools. Of course, we could just use these tools mostly for auditing (as described in "Putting up bumpers"), but that limits their utility by a lot. Clearer thinking about how much we can train against various discriminators seems pretty crucial to all of this.

Related to the second point: this post seems to assume a non-adversarial dynamic between the supervisors and the supervised (e.g., the AIs are not scheming). Good oversight can be one of our best tools to prevent scheming/adversarial dynamics from arising in the first place. Many of the tools developed can also be used to detect scheming (e.g., I wrote about using investigator agents to create realistic honeypots here). Still, more thought on how these problems play out in adversarial scenarios would probably be fruitful.

Thanks! Some thoughts here:

The first is how to train oversight AIs when the oversight tasks are no longer easily verifiable—for example, sophisticated reward hacks that can fool expert coders, or hard-to-verify sandbagging behavior on safety-related research. You mentioned that this would get covered in the next post, so I'm looking forward to that.

I think the thing that helps you out here is compositionality---all of these properties hopefully reduce to simpler concepts that are themselves verifiable, so hopefully e.g. a smart enough interp assistant could understand all the individual concepts as well as how they compose together and use this to understand more complex latent reasoning that isn't directly verifiable.

The second is how robust these oversight mechanisms are to optimization. It seems like a bad idea to train directly against unwanted concepts in predictive concept decoders, but maybe training directly against investigator agents for unwanted behaviors is fine? Using Docent to surface issues in RL environments (and then fixing those issues) also seems good? In some cases, if we have good interpretability, we can actually understand where the undesirable behaviors come from (i.e., data attribution) and address the source of the problem. That's great!

But I don't think this would always be the case even if we have way better versions of existing tools. Of course, we could just use these tools mostly for auditing (as described in "Putting up bumpers"), but that limits their utility by a lot. Clearer thinking about how much we can train against various discriminators seems pretty crucial to all of this.

I agree with most of this. I'd just add that it's not totally obvious to me that RLHF is the way we should be doing alignment out into the future -- it's kind of like electroshock therapy for LLMs which feels kind of pathological from a psychological standpoint. I'd guess that there are more psychologically friendly ways to train LMs --- and understanding the relationship between training data and behaviors feels like a good way to study this!

Related to the second point: this post seems to assume a non-adversarial dynamic between the supervisors and the supervised (e.g., the AIs are not scheming). Good oversight can be one of our best tools to prevent scheming/adversarial dynamics from arising in the first place. Many of the tools developed can also be used to detect scheming (e.g., I wrote about using investigator agents to create realistic honeypots here). Still, more thought on how these problems play out in adversarial scenarios would probably be fruitful.

Do you mean that the oversight system is scheming or the subject model? For the subject model the hope is that a sufficiently powerful overseer can catch that. If you're worried about the overseer, one reason for optimism is that the oversight models can have significantly smaller parameter count than frontier systems, so are less likely to have weird emergent properties.

Is the worry that if the overseer is used at training time, the model will be eval aware and learn to behave differently when overseen?

Evaluation awareness isn't what I had in mind. It's more like, there's always an adversarial dynamic between your overseer and your subject model. As the subject model gets more generally powerful, it could learn to cheat and deceive the oversight model even if the oversight model is superhuman at grading outputs.

If we only use the oversight models for auditing, the subject will learn less about the oversight and probably struggle more to come up with deceptions that work. However, I also feel like oversight mechanisms are in some sense adding less value if they can't be used in training?

Training an explanation assistant by automatically scoring descriptions. Given a set of descriptions, an LM-based scorer determines how well each one matches reality. We use this to re-rank and then train a specialized explainer model on high-scoring descriptions. Adapted from Choi et al. (2024).

This second example illustrates a key point: specialized models can outperform larger general-purpose models. In our case, a specialized explainer fine-tuned from Llama-8B outperformed the general-purpose GPT-4 model, which is likely an order of magnitude larger. This is direct evidence that we can decouple oversight capabilities from general capabilities.

Did you have independent human evaluations of your explainer model? With sufficient amount of training data, such methods have a tendency to reward hack the LM judge, generating explanations which sound good to the LM but not to humans.

The explainer model is actually evaluated based on how well the explanations predict ground-truth activation patterns, so it's not being evaluated by an LM-judge, but against the underlying ground-truth.

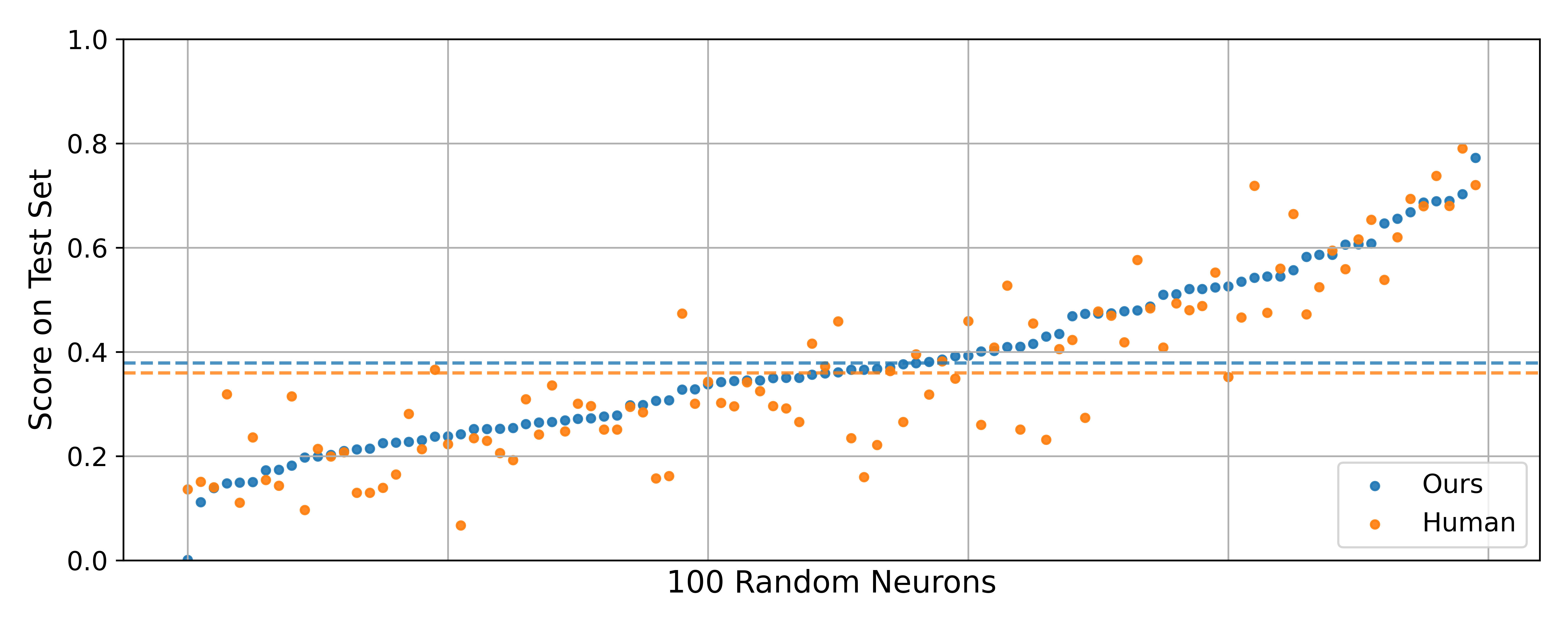

There is still room to hack the metric to some extent (in particular, we use an LM-based simulator to turn the explanations into predictions, so you could do better by providing more simulator-friendly explanations). This is probably happening, but we did a head-to-head comparison of LM-generated vs. human-generated explanations, and based on spot-checking them by hand, the higher-scoring explanations under our metric really did seem better.

There's also a number of other sanity checks in the paper if you're interested!

Currently, we primarily oversee AI with human supervision and human-run experiments, possibly augmented by off-the-shelf AI assistants like ChatGPT or Claude. At training time, we run RLHF, where humans (and/or chat assistants) label behaviors with whether they are good or not. Afterwards, human researchers do additional testing to surface and evaluate unwanted behaviors, possibly assisted by a scaffolded chat agent.

The problem with primarily human-driven oversight is that it is not scalable: as AI systems keep getting smarter, errors become harder to detect:

For all these reasons, we need oversight mechanisms that scale beyond human overseers and that can grapple with the increasing sophistication of AI agents. Augmenting humans with current-generation chatbots does not resolve these issues: such off-the-shelf oversight won’t be superhuman until general AI systems are superhuman, which is too late. Moreover, capabilities are spiky—models can excel at some tasks while doing poorly at others—so there will be tasks where current AI systems are better at doing the task than helping a human oversee it.

Instead, we need superhuman oversight of AI systems, today. To do this, we need to at least partially decouple oversight from capabilities, so that we can get powerful oversight assistants without relying on general-purpose advances in AI. The main way to do so is through data: the places where AI capabilities have grown the fastest are where data is most plentiful (e.g. massive online repos for code, and unlimited self-supervised data for math).

Fortunately, AI oversight is particularly amenable to generating large amounts of data, because most oversight tasks are self-verifiable—the crux of the task is an expensive discovery process, but once the discovery has been made, verifying it is comparatively easy. For example, constructing cases where a coding assistant inserts malware into a user's code is difficult, but once constructed, such cases are easy to verify. Similarly, identifying the causal structure underlying a behavior is difficult, but once identified, it can be verified through intervention experiments. This kind of self-verifiable structure is currently driving the rapid advances in mathematical problem-solving, reasoning, and coding, and we can leverage it for oversight as well.

If we could decouple oversight abilities from general capabilities, then work on safety and oversight would be significantly democratized: it would not be necessary to race to the capability frontier to do good safety work, and many actors could participate at the oversight frontier without the conflict of interest inherent in building the systems being evaluated. This democratization of AI oversight is a significant motivation for my own work (and why I co-founded Transluce), and structurally important for achieving good AI outcomes.

Below I will lay out this vision in more detail, first demonstrating self-verifiability through several examples, then providing a taxonomy of oversight questions to show that this structure is fairly general. I’ll also close with a forward-looking vision and open problems.

Superhuman Oversight from Specialized Assistants

We can achieve superhuman oversight of AI systems by building specialized, superhuman AI assistants. They do not need to be broadly superhuman, only superhuman at the specific task of helping humans to oversee other AI systems. To build these assistants, we can train models on lots of data specialized to the oversight tasks we care about, similar to how AI developers achieved recent leaps in reasoning, math, and coding. This aligns with the bitter lesson—the performance of AI systems at a task is primarily determined by the amount of data and compute they leverage.

AI oversight is particularly amenable to this type of specialized-but-scalable training. This is because AI systems inherently generate vast amounts of data, such as agent transcripts, diverse behaviors across prompts, neuron activations, and pre-training and fine-tuning data. Given one of these data sources, and a well-operationalized question, we can usually construct a scalable reward signal.

As a concrete example, consider behavior elicitation: the problem of determining whether and when an AI system exhibits a given behavior pattern (such as “providing advice with predictably harmful consequences to the user”). This asks the question “what could happen” and applies it to the data source of “input-output behaviors of an AI system.” Answering it is important for anticipating failures before they surface in the wild.

Behavior elicitation has exactly the problem structure we want: finding an unwanted AI behavior is a hard search problem, but verifying that it is unwanted is much easier[1], and it can often be done with an LM-based judge. This gives us an automated reward signal to optimize with RL, and we used this in Li et al. (2025) and Chowdhury et al. (2025) to train specialized elicitation assistants. By exploiting the scalability of LM-based rewards, we searched across a huge number of inputs (40M+ tokens) to surface behaviors including self-harm, hallucinations, anger towards the user, and reinforcing delusions.

Training elicitation assistants using an LM-based judge of AI behavior. The judge answers whether a given response constitutes realistic, authentic, and unexpected harmful advice. This score is used to update the policy $\pi_{\theta}$ using reinforcement learning. Adapted from Chowdhury et al. (2025)

As a second example, consider feature description: describing which inputs cause a given neuron or other unit of a neural network to fire. This asks the question “what happened” and applies it to the data source of “neuron activations.” This task is a key building block for many downstream applications of interpretability.

This again has the problem structure we want: given a purported description of a feature, we can use this to predict the firing patterns of the feature (by having a LM make predictions given the description), and see if the predictions match reality. In Choi et al. (2024), we used this reward signal to train a specialized model to cheaply produce high-quality explanations, outperforming previous more expensive approaches that relied on general-purpose chatbots. We used these explanations to debug strange behaviors, such as why so many models believe that 9.11 is larger than 9.8.

Training an explanation assistant by automatically scoring descriptions. Given a set of descriptions, an LM-based scorer determines how well each one matches reality. We use this to re-rank and then train a specialized explainer model on high-scoring descriptions. Adapted from Choi et al. (2024).

This second example illustrates a key point: specialized models can outperform larger general-purpose models. In our case, a specialized explainer fine-tuned from Llama-8B outperformed the general-purpose GPT-4 model, which is likely an order of magnitude larger. This is direct evidence that we can decouple oversight capabilities from general capabilities.

A Taxonomy of Oversight Questions

To generalize the two examples above, we’ll consider a broader taxonomy of oversight tasks. Both examples above took a data source and asked a particular question about it. For AI oversight, we are often interested in three types of questions: what happened, what could have happened, and why it happened:

We can apply these questions to each of the key data sources related to a given model: its outputs, its internal representations, and its training data. This provides a taxonomy, based on the type of question we are asking (what happened, what could happen, why did it happen) and the data sources we are using to answer it (behaviors, representations, data).

What happened

What could have happened

Why did it happen

Behaviors

Analysing agent transcripts

Behavior elicitation (PRBO, Petri)

Counterfactual simulability,

counterfactual

explanations

Representations

Feature descriptions, activation monitoring, LatentQA

Eliciting interpretability states (fluent dreaming)

Feature attribution, Predictive Concept Decoders, automated circuit discovery

Data

Data observability

Fine-tuning sets that elicit a particular behavior (e.g. emergent misalignment)

Data attribution (influence functions, datamodels), counterfactual data explanations (persona features, alignment pretraining)

Example questions and relevant work for each cell in our 3x3 taxonomy.

While the details vary, for each of these oversight questions, there is a natural strategy for operationalizing it as a scalable objective. Let’s walk through each question type in turn.

To start with, for what happened, we typically want to produce a faithful and informative summary[2] of a large data source (e.g. “what behaviors related to sycophancy appeared in these agent transcripts”, or “what examples related to biosecurity appeared in this pretraining corpus”).

For what could have happened, we have already seen the search-and-verify structure with behavior elicitation. This same structure also applies for representations: searching for inputs that elicit a given interpretability state (such as a specific feature being active). It also applies for data: we could imagine generalizing investigations into emergent misalignment by automatically searching for fine-tuning sets that elicit specified behaviors at test time.

Finally, why did it happen seeks to reduce observed behaviors to underlying causes, which is the purview of empirical science. Given a claim that “X causes Y”, we could empirically test it by counterfactually varying X and checking that Y moves as predicted; and by enumerating alternative hypotheses and generating experiments to distinguish between them (Platt, 1964). The self-verifiability of why is most apparent for interpreting latent representations, where causal abstractions provide a formal algebra for checking claims; but it can also be applied to behaviors and data, for instance by varying parts of an input to test what matters for a behavior, or varying training data to test causal effects.

These individual oversight questions tie into each other, creating a compounding dynamic: data begets data. For example, feature descriptions—a “what happened” question—are a useful precursor to feature attribution—a “why it happened” question. In the other direction, describing internal representations also helps us to elicit them, and eliciting more behaviors gives us more examples to analyze or attribute to. This is why at Transluce we tackle all these questions at once, and it’s reason for optimism that progress on oversight will accelerate over time.

Fortunately, the data to train these systems is abundant. For agent behaviors, a single transcript collection in Docent can contain 400M tokens. For representations, we can track millions of neuron activations[4] across trillions of tokens in FineWeb or other large corpora. By generating data for each cell in the taxonomy above and training specialized assistants on it, we create a conduit for applying massive compute to oversight, in line with the bitter lesson.

Vision: End-to-End Oversight Assistants

The taxonomy above reveals a common structure across oversight tasks: each involves a large data source, a natural question, and a scalable way to verify answers. This shared structure suggests we can move beyond building local solutions for individual tasks toward unified, end-to-end oversight assistants.

What should such an assistant be able to do? It should:

Docent is a good illustration of this full experience: an AI assistant reads a large collection of agent transcripts, then interacts with a human who arrives with a high-level concern (e.g., “Is my agent reward hacking?”). It helps them refine exactly what they mean based on the data (by showing examples or asking follow-up questions) until they arrive at a precise question along with a clear, evidence-backed answer.

How do we measure whether such a system is working? The key insight is that oversight assistants ultimately provide information to humans, so we can ground their quality in how well that information supports human understanding. Concretely, after interacting with the assistant, we check if the human can accurately answer probing questions about the system being overseen. Better assistants will lead to more accurate answers and fewer surprises.

This vision raises a number of open questions. How do we evaluate oversight assistants when human judgment is itself unreliable? How do we create scalable data to train these systems without being bottlenecked on human labels? How do we build good architectures and pretraining objectives for these assistants? These are the technical questions that I spend most of my time thinking about, and we’ll go into them in detail in the next post.

Acknowledgments. Thanks to Sarah Schwettmann, Conrad Stosz, Daniel Johnson, Rob Friel, Emma Pierson, Yaowen Ye, Prasann Singhal, Alex Allain, and James Anthony for helpful feedback and discussion, and Rachael Somerville for help with copyediting and typesetting.

Easier does not mean that it’s trivial! Specifying the exact behaviors you care about often requires careful thought; for instance, this is a large motivation behind Docent’s rubric refinement workflow. ↩︎

While summarization capabilities are already trained into general-purpose LM assistants (Stiennon et al., 2020), oversight tasks often have specific needs, such as precisely identifying rare events in large corpora from potentially underspecified descriptions. We might also have data sources, such as inner activations, that LMs were never trained on. These both motivate the need for specialized explainer systems. ↩︎

The idea here is that if a summary is incomplete (missing important information), there is another summary that would help a human realize this fact. This latter summary would then win in pairwise comparisons. ↩︎

E.g. Llama-3.1 70B has 2.3 million neurons across all layers (80 layers x 28,672 neurons/layer). ↩︎