I think this is really cool work! I'm excited about more work on improving rigor of circuit faithfulness metrics. Some more comments:

We've been seeing similar things when pruning graphs of language model computations generated with parameter decomposition. I have a suspicion that something like this might be going on in the recent neuron interpretability work as well, though I haven't verified that. If you just zero or mean ablate lots of nodes in a very big causal graph, you can get basically any end result you want with very few nodes, because you can select sets of nodes to ablate that are computationally important but cancel each other out in exactly the way you need to get the right answer.[1]

I think the trick is to not do complete ablations, but instead ablate stochastically or even adversarially chosen subsets of nodes/edges:

This way, you also don't need to freeze layer norms to prevent cheating.

It's for a different context, but we talk about the issue with using these sorts of naive ablation schemes to infer causality in Appendix A of the first parameter decomposition paper. This is why we switched to training decompositions with stochastically chosen ablations, and later switched to training them adversarially.

There's some subtlety to this. You probably want certain restrictions placed on the adversary, because otherwise there's situations where it can also break faithful circuits by exploiting random noise. We use a scheme where the adversary has to pick one ablation scheme for a whole batch, specifying what nodes it does or does not want to ablate whenever they are not kept, to stop it from fine tuning unstructured noise for particular inputs.

similar masking techniques can achieve good performance on vision tasks even when applied to a model with random weights.

Isn't this just the lottery ticket hypothesis? If you search through enough randomly shaped pieces of metal, you will eventually find a usable screw. That doesn't prove that looking at a screw tells you nothing about its intended purpose.

LHT says (emphasis mine):

dense, randomly-initialized, feed-forward networks contain subnetworks ("winning tickets") that - when trained in isolation - reach test accuracy comparable to the original network in a similar number of iterations

Note that in LHT the subnetworks are trained, unlike in the results I cited.

So in their case, they're finding a random piece of metal sufficiently helical-with a blob-on-one-end that it can be efficiently trained into being a screw? Which does indeed sound a lot easier to find.

I stand corrected.

TLDR: Recently, Gao et al trained transformers with sparse weights, and introduced a pruning algorithm to extract circuits that explain performance on narrow tasks. I replicate their main results and present evidence suggesting that these circuits are unfaithful to the model’s “true computations”.

This work was done as part of the Anthropic Fellows Program under the mentorship of Nick Turner and Jeff Wu.

Introduction

Recently, Gao et al (2025) proposed an exciting approach to training models that are interpretable by design. They train transformers where only a small fraction of their weights are nonzero, and find that pruning these sparse models on narrow tasks yields interpretable circuits. Their key claim is that these weight-sparse models are more interpretable than ordinary dense ones, with smaller task-specific circuits. Below, I reproduce the primary evidence for these claims: training weight-sparse models does tend to produce smaller circuits at a given task loss than dense models, and the circuits also look interpretable.

However, there are reasons to worry that these results don't imply that we're capturing the model's full computation. For example, previous work [1, 2] found that similar masking techniques can achieve good performance on vision tasks even when applied to a model with random weights. Therefore, we might worry that the pruning method can “find” circuits that were not really present in the original model. I present evidence that the worry is justified—namely, pruned circuits can:

Overall, these results suggest that circuits extracted from weight-sparse models, even when interpretable, should be scrutinized for faithfulness. More generally, in interpretability research, we should not purely try to push the Pareto frontier of circuit size and task performance,[1] since doing so may produce misleading explanations of model behavior.

In this post, I briefly review the tasks I designed to test the sparse model methods, present a basic replication of the major results from Gao et al, and then give four lines of evidence suggesting that their pruning algorithm produce unfaithful circuits.

My code for training and analyzing weight-sparse models is here. It is similar to Gao et al's open-source code, but it additionally implements the pruning algorithm, “bridges” training, multi-GPU support, and an interactive circuit viewer. Training also runs ~3x faster in my tests.

Tasks

I extract weight-sparse circuits via pruning on the following three natural language tasks. For more details on training and pruning, see the appendix.

Task 1: Pronoun Matching

Prompts have the form "when {name} {action}, {pronoun}"

For example:

The names are sampled from the 10 most common names (5 male, 5 female) from the pretraining set (SimpleStories).[2] The task loss used for pruning is the CE in predicting the final token ("he" or "she").

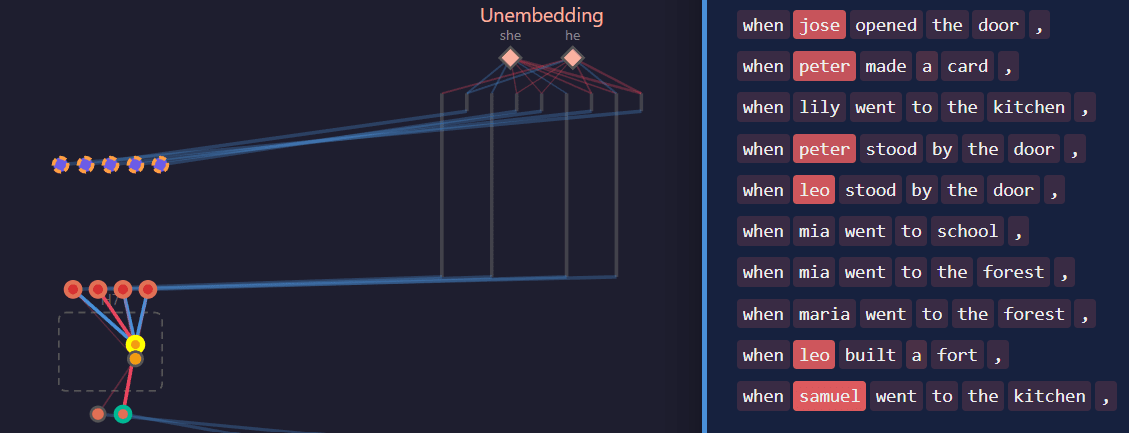

Task 2: Simplified IOI

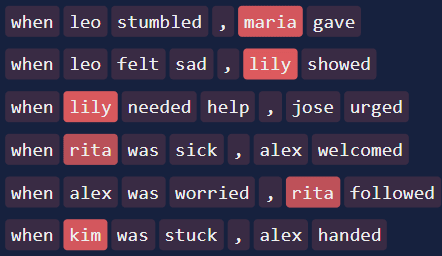

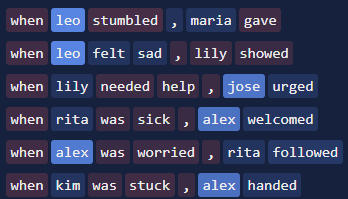

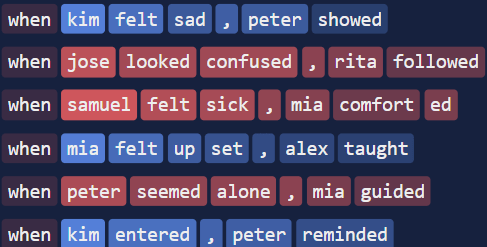

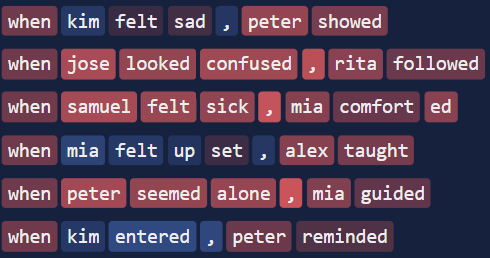

I use a simplified version of the standard Indirect Object Identification task. Prompts have the form "when {name_1} {action}, {name_2} {verb} {pronoun matching name_1}". E.g.:

The task loss used for pruning is the binary CE: we first compute the model’s probability distribution just over "him" and "her" (softmaxing just those two logits) and then compute the CE using those probabilities.

Task 3: Question Marks

The prompts are short sentences from the pretraining set that either end in a period or a question mark, filtered to keep only those where 1) the dense model predicts the correct final token (period or question mark) with p > 0.3, and 2) when restricted to just the period and question mark, the probability that the dense model assigns to the correct token is > 0.8. For example:

The task loss used for pruning is the binary CE, softmaxing only the "?" and "." logits.

Results

See the appendix for a slightly tangential investigation into the role of layer norm when extracting sparse circuits.

Producing Sparse Interpretable Circuits

Zero ablation yields smaller circuits than mean ablation

When pruning, Gao et al set masked activations to their mean values over the pretraining set. I found that zero-ablation usually leads to much smaller circuits at a given loss (i.e. in all subplots below except the third row, rightmost column). Hence I used zero-ablation for the rest of the project.

Weight-sparse models usually have smaller circuits

Figure 2 from Gao et al mostly replicates. In the pronoun and IOI tasks, the sparse models have smaller circuits than the dense model, at a given loss. On the question task, only two of the sparse models have smaller circuits than the dense one, and even then, the reduction in size is smaller than it was for the other two tasks.

Weight-sparse circuits look interpretable

You can view circuits for each task here. Hovering over/clicking on a node shows its activations, either in the original or the pruned model. Below is a brief summary of how I think the IOI circuit works; I walk through circuits for the other two tasks in the appendix. Each circuit I walk through here was extracted from the dmodel=1024 model; I did not inspect circuits extracted from the other models as carefully. All the per-token activations shown in this section are taken from the pruned model, not the original model.

IOI Task (view circuit)

Below is an important node from layer 1 attn_out. It activates positively on prompts where name_1 is female and negatively on prompts where it is male. It then suppresses the "him" logit.

To see how this node’s activation is computed, we can inspect the value-vector nodes it reads from, and the corresponding key and query nodes. The value-vector node shown below activates negatively on male names:

There are two query-key pairs. The first query vector always has negative activations (not shown). The corresponding key node’s activation is negative, with magnitude roughly decreasing as a function of token position:

The other query-key pair does the same thing but with positive activations. Hence the head attends most strongly to the first part of the prompt, and so the attn_out node only gets a large contribution from the value-vector node when it appears near the start of the sentence. Specifically, the attn_out node gets a large negative contribution when name_1 is male. The other value-vector node, not shown here, gives a positive contribution when name_1 is female. This explains the activation patterns we saw above for the attn_out node.

Scrutinizing Circuit Faithfulness

Pruning achieves low task loss on a nonsense task

I alter the pronouns task so that when the name is male, the target token is "is", and when the name is female, the target is "when". E.g.:

Just like the standard pronouns task, the task loss is just the standard CE loss (i.e. all logits are softmaxed. I am not using the binary CE). This is a nonsense task, but the pruned model gets task loss < 0.05 (meaning accuracy >95%) with only ~30 nodes.

Around 10 nodes are needed to achieve a similar loss on the ordinary pronouns task. So the nonsense task does require a larger circuit than the real task, which is somewhat reassuring. That said, it seems worrying that any circuit at all is able to get such low loss on the nonsense task, and 30 nodes is really not many.

You can view the nonsense circuit here.

Important attention patterns can be absent in the pruned model

This pronouns circuit has attention nodes only in layer 1 head 7. In the original model, this head attends strongly from the last token to the name token ("rita"), as one would expect. But in the pruned model, its attention pattern is uniform (since there are no query- or key-vector nodes):

How does the pruned circuit get away with not bothering to compute an attention pattern? It does so by having all its value-vector nodes be ones that fire strongly on names and very weakly everywhere else. So even though the head attends to all tokens, it only moves information from the name token. Such a mechanism was not available to the original model. The circuit we found misses a crucial part of what the original model was doing.

Nodes can play different roles in the pruned model

Example 1: Below are the activations of layer 0, node 1651 from this IOI circuit. The left figure shows its activations in the pruned model, where it activates negatively (red) on female names. The right figure shows its activations in the original model, where it activates positively (blue) on male names. In both cases, its activation is very close to zero for all non-name tokens. This is strange: the node acquires a different meaning after pruning.

Example 2: Below are activations of attn_out, layer 1, node 244 from this IOI circuit. In the pruned model, the node activates positively on contexts where name_1 (the first-appearing name) is female, and negatively on ones where it is male. In particular, the final token’s activation is positive only if name_1 is female, and as expected, the node directly suppresses the "him" logit. So, in the pruned model, the node is playing the functional role “detect gender of name_1 and boost/suppress corresponding logit”. But in the original model, the final token’s activation does not depend on name_1, so it cannot be playing the same functional role.

Example 3: Below are activations of mlp_out, layer 1, node 1455 from this Questions circuit. In the pruned model, the node is a questions classifier: its activations are negative on questions and roughly zero elsewhere. It is used to suppress the "?" logit. But in the original model, it is not a question classifier. In particular, its activation on the last token of a sentence does not predict whether or not the sentence was a question, and so it cannot be helping to promote the correct logit.

Pruned circuits may not generalize like the base model

Recall that IOI prompts look like "when {name_1} was at the store, {name_2} urged __". We prune using a train set consisting only of prompts where name_1 and name_2 have opposite genders. There are two obvious circuits that get good performance on the train set:

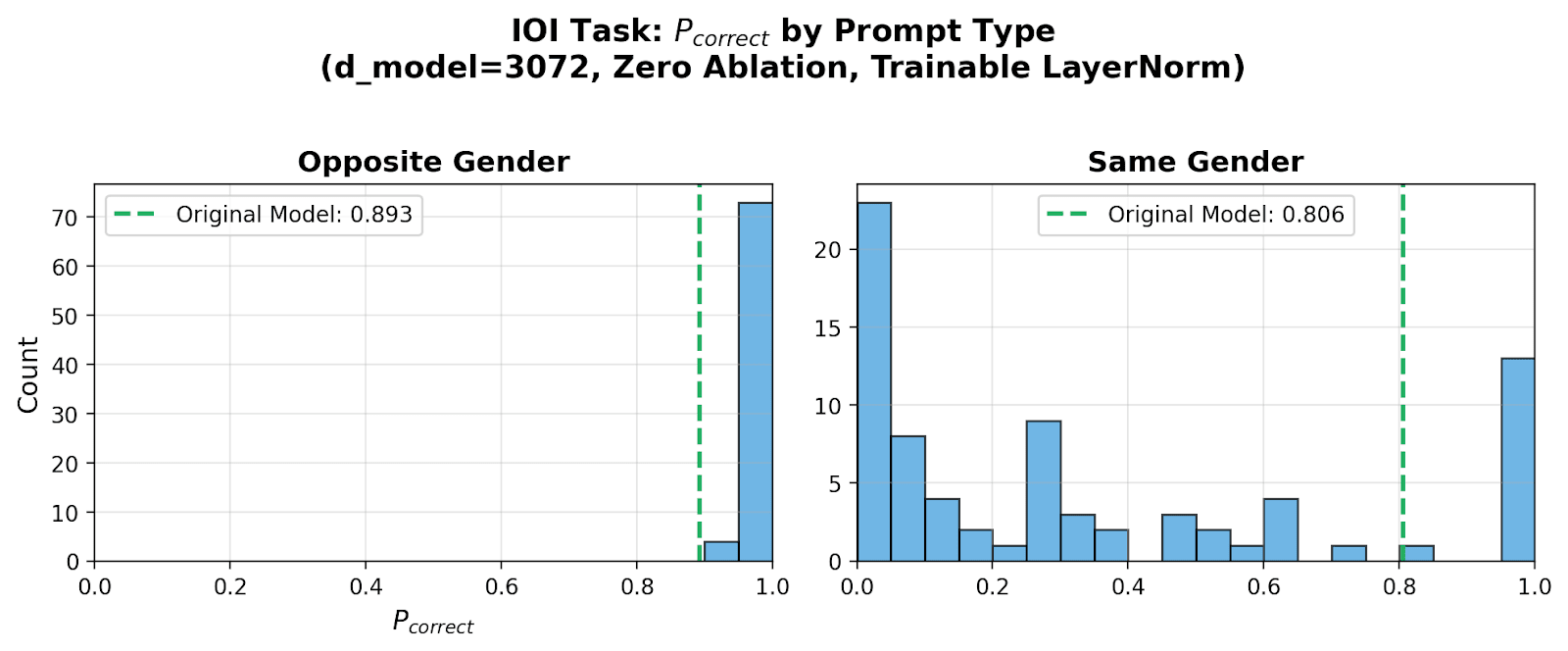

Let Pcorrect be the mean probability assigned to the correct target token, where we compute the probability by only softmaxing the him and her tokens. Here, I focus on the model with dmodel=3072, which completes the task correctly 89% of the time for opposite-gender prompts, and 81% of the time for same-gender prompts.

I run pruning 100 times with different random mask initializations and data ordering. Below I show the resulting distribution of Pcorrect for opposite-gender prompts (left) and same-gender prompts (right). I filter out runs which didn’t achieve CE < 0.15, leaving 77 seeds total.

Often, pruning finds only the “bad circuit” (see the big spike at 0 in the same-gender histogram). This is bad, since the actual original model had Pcorrect=0.81 in the same-gender case and so must have been using the good circuit.

Separately, it is also a little worrying that pruning using the same hyperparameters but different random seeds can lead circuits with totally different OOD behavior.

Conclusion

The above results provide evidence that Gao et al's pruning method can find circuits that are small, interpretable, and get good task loss, but nevertheless are unfaithful to what the model is really doing. These results do not have much to say about whether weight-sparse training itself is a promising direction; they only show that the pruning algorithm is flawed.

My main takeaway is that we should not purely aim to improve the loss vs circuit size Pareto frontier. Hill-climbing on this metric alone is likely to yield mechanistic explanations that look appealing but are actually misleading. For example, zero ablation improved the frontier, so I switched to it early on. But in hindsight, mean ablation may have given more faithful circuits (at the cost of giving circuits with ~100 nodes for a task as simple as pronoun gender matching, which is a lot more than I would’ve hoped for).

I think a natural next step for the weight-sparsity line of work would be to 1) think of a good faithfulness metric[3] (ideas like causal scrubbing seem on the right track but possibly too strict); 2) figure out how to modify the pruning algorithm to extract circuits that are faithful according to that metric; 3) check whether Gao et al’s main result—that weight-sparse models have smaller circuits—holds up when we use the modified pruning algorithm.[4]

I would also be interested in applying similar scrutiny to the faithfulness of attribution graphs.[5] I expect attribution graphs to be more faithful than the circuits I found in the present work (roughly speaking, because the way they are pruned does not optimize directly for downstream CE loss), but someone should check this. I’d be particularly interested in looking for cases where attribution graphs make qualitatively-wrong predictions about how the model will behave on unseen prompts (similar to how pruning found the “bad circuit” for the IOI task above).

Appendix A: Training and Pruning Details

My implementation of weight-sparse training is almost exactly copied from Gao et al. Here I just mention a few differences and points of interest:

For pruning, I once again follow Gao et al closely, with only small differences:

Appendix B: Walkthrough of pronouns and questions circuits

Pronouns Task (view circuit)

All the computation in this circuit routes through two value-vector nodes in layer 1. The one shown below activates negatively on male names. There are no query or key nodes, so attention patterns are uniform, and each token after the name gets the same contribution from this value-vector node. Tracing forward to the logit nodes, one finds that this value-vector node boosts "she" and suppresses "he". The other value-vector node does the same but with genders reversed.

Notice that the mlp_out nodes in layer 1 have no incoming weights connecting to upstream circuit nodes, so their activations are constant biases.

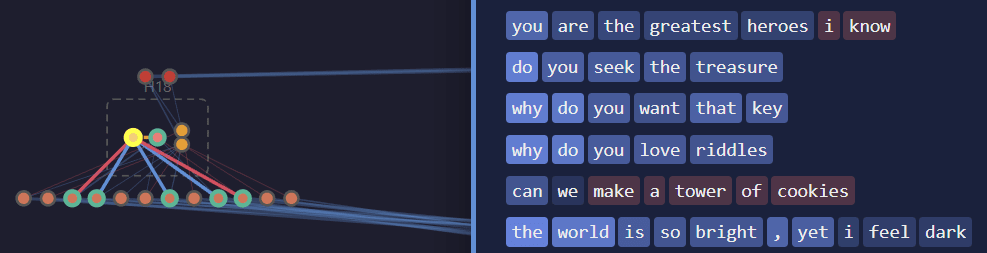

Questions Task (view circuit)

The earliest node that acts as a question classifier is at attn_out in layer 1:

This attn_out node reads from a value node that activates positively on “question words” (“why”, “are”, “do” and “can”) and negatively on pronouns:

The query node for that head has positive activations (not shown). The key node’s activations roughly[6] decrease as a function of token position:

Thus, if a prompt contains “do you” then the head attends more strongly to “do”, so attn_out receives a large positive contribution from the question word “do” and only a small negative contribution from the pronoun “you”. On the other hand, if the prompt contains “you do”, then the head attends more strongly to “you” so attn_out receives a large negative contribution from “you” and only a small positive contribution from “do”.

Putting that all together, the attn_out node activates positively on prompts containing “do you” and negatively on prompts containing “you do”, and similarly for other combinations of question words and pronouns. Hence the attn_out node functions as a question detector.

Appendix C: The Role of Layernorm

Pruned models get very low task loss with very few nodes. Here is one way they might be “cheating”:

Pruning decreases activations’ norms. In particular, the plot below shows that the RMS of the residual stream just after the last layer—i.e. the activation that is fed into the final layernorm—is smaller in the pruned model. So the final layernorm scales up activations by a larger factor in the pruned model than it did in the original model.

Now, suppose the original model has many nodes which each write a small amount to the “correct direction” just before the final layernorm, by which I mean the direction that will unembed to boost the correct logit. The pruned circuit contains only a small number of these nodes, so it only writes a small amount to the correct direction. But it gets away with this, because the final layernorm scales the activation up a lot, so that even a small component in the correct direction will strongly boost the correct logit, leading to good CE loss.

Below, we compare regular pruning against a modified version where we freeze layernorm scales (the thing layernorm divides activations by). That is, for each batch of data, we run the original model, save all its layernorm scales, then patch them into the pruned model during its forward pass. As the above analysis predicts, freezing layernorm leads to much larger circuits at a given loss.

For the IOI task with the larger (dmodel=3072) model, freezing layernorm (bottom) leads to better generalization to same-gender prompts than standard pruning (above):

However, the results are the opposite for the smaller (dmodel=1024) model. That is, freezing layernorm leads to circuits which generalize worse than when layernorm was unfrozen. I found this result surprising.

I think it is “morally correct” to freeze layernorm during pruning, so that the model cannot cheat in the way described above. But it seems doing so does not fully fix the faithfulness issues (see the IOI dmodel=1024 results directly above).

A final caveat to the results in this appendix: for each model and task, I performed a CARBS sweep to find the best hyperparameters for pruning, and then used these best hyperparameters for each of the 100 randomly-seeded pruning runs. It may be the case that e.g. for the dmodel=1024 we happened to find "unlucky" hyperparameters that lead to poor generalization to same-gender prompts, whereas we got "lucky" with the hyperparameters we found for the dmodel=3072 model. In other words, the 100 seeds are perhaps not as decorrelated as we'd like.

Where smaller circuit size and lower CE loss are better. In this work, circuit size refers to the number of nodes in the circuit.

In case you're curious, the names are Leo, Samuel, Jose, Peter, Alex, Mia, Rita, Kim, Maria, Lily.

E.g. I tried defining the "importance" of each node in the model as the increase in task loss when the node is ablated, and then computing the fraction of the top 20 (say) most important nodes that are present in the circuit. All circuits I looked at scored poorly on this metric. But the supposedly-important nodes that were not found in the circuit often had dense, seemingly-uninterpretable activations (I saw this both for mean- and zero-ablation), and I suspect they are playing a very low-level "keeping activations on-distribution" sort of role, similar to a constant bias term. So I am not convinced judging faithfulness via importance score defined above is quite right.

If you’re interested in doing this sort of work, please get in touch at jacobcd52 at gmail dot com.

E.g. I'd love to see more work like this.

The fact that the activations only roughly decrease as a function of token position makes me suspect that my mechanistic explanation is missing parts. Probably the attention patterns are more nuanced than just "any old roughly-decreasing function", but I haven't tried hard to understand them.