Grats on getting this out! I am overall excited about exploring models that rely more on uplift than on time horizons. A few thoughts:

It might be nice to indicate how these outputs relate to your all-things-considered views. To me your explicit model seems to be implausibly confident in 99% automation before 2040.

In particular, the "doubling difficulty growth factor", which measures whether time horizon increases superexponentially, could change the date of automated coder from 2028 to 2049! I suspect that time horizon is too poorly defined to nail down this parameter, and rough estimates of more direct AI capability metrics like uplift can give much tighter confidence intervals.

I am skeptical that uplift measurements actually give much tighter confidence intervals.

After talking to Thomas about this verbally, we both agree that directly using uplift measurements rather than time horizon could plausibly be better by the end of 2026, though we might have different intuitions about the precise likelihood.

Effective labor/compute ratio only changes by 10-100x during the period in question, so it doesn't affect results much anyway. The fastest trajectories are most affected by compute:labor ratio, but for trajectories that get to 99% automation around 2034, the ratio stays around 1:1.

This isn't true in our model because we allow full coding automation. Given that this is the case in your model, Cobb-Douglas seems like a reasonable approximation.

I am skeptical that uplift measurements actually give much tighter confidence intervals.

I think we might already have evidence against longer timelines (2049 timelines from doubling difficulty growth factor of 1.0). Basically, the model needs to pass a backtest against where uplift was in 2025 vs now, and if there's significant uplift now and wasn't before 2025, this implies the automation curve is steep.

Suppose uplift at the start of 2026 was 1.6x as in the AIFM's median (which would be 37.5% automation if you make my simplifying assumptions). If we also know that automation at start of 2025 was at most 20%, this means automation is increasing at 0.876 logits per year, or per ~8x time horizon factor, or 45x effective compute factor etc. (If d.d.g.f is 1.0, automation is logistic in both log TH and log E.) At this slope, we get to 95% AI R&D automation (or in your model, ~100% coding automation) when we hit a time horizon of 14 years, which is less than your median of 125 years and should give timelines before 2045 or so. Uplift might be increasing even faster than this, in which case timelines will be shorter. We don't have any hard data on uplift quite yet, but I suspect that our guesses at uplift should already make us downweight longer timelines, and in Q2 or Q3 I hope we can prove it.

I would still put some weight on longer timelines, but to me this uncertainty doesn't live in something like d.d.g.f. My understanding of the AIFM is that uncertainty in all the time horizon parameters cashes out in the effective compute required for uplift. In this frame, the remaining uncertainty lives in whether the logistic curve in log E holds-- whether ease of automation in the future is similar to ease of early-stage automation we're already observing.

It might be nice to indicate how these outputs relate to your all-things-considered views. To me your explicit model seems to be implausibly confident in 99% automation before 2040.

Yeah, my all-things-considered views are definitely more uncertain. I don't have well-considered probabilities-- I'd probably need to think about it more and perhaps build more simple models that apply in long-timelines cases.

Suppose uplift at the start of 2026 was 1.6x as in the AIFM's median

Where are you getting this 1.6 number?

With respect to the rest of your comment, it feels to me like we have such little evidence about current uplift and what trend it follows (e.g. whether this assumption about a % automation curve that is logistic and its translation to uplift is a reasonable functional form). I'm not sure how strongly we disagree though. I'm much more skeptical of the claim that uplift can give much tighter confidence intervals than that it can give similar or slightly better ones. Again, this could change if we had much better data in a year or two.

I got it from your website:

Our median value for the coding uplift of present-day AIs at AGI companies is that having the AIs is like having 1.6 times as many software engineers (and all the staff necessary to coordinate them effectively).

As for the rest, seems reasonable. I think you can't get around the uncertainty by modeling uplift as some more complicated function of coding automation fraction as in the AIFM, because you're still assuming that's logistic, we can't measure it any better than uplift, plus we're still uncertain how they're related. So we really do need better data.

I think you can't get around the uncertainty by modeling uplift as some more complicated function of coding automation fraction as in the AIFM, because you're still assuming that's logistic, we can't measure it any better than uplift, plus we're still uncertain how they're related. So we really do need better data.

But in the AIFM the coding automation logistic is there to predict the dynamics regarding how much coding automation speeds progress pre-AC. It doesn't have to do with setting the effective compute requirement for AC. I might be misunderstanding something, sorry if so.

Re: the 1.6 number, oh that should actually be 1.8 sorry. I think it didn't get updated after a last minute change to the parameter value. I will fix that soon. Also, that's the parallel uplift. In our model, the serial multiplier/uplift is sqrt(parallel uplift).

In my model it's parallel uplift too. Effective labor (human+AI) still goes through the diminishing returns power

This is interesting. Caveating the below as a "research note comment" in a similar spirit to the caveats around the above being a "research note":

1. Generalizing the model to include bottlenecks

- I generalized the model to have R be CES over L and C, rather than Cobb-Douglas --> to allow for bottlenecks

- Based on conversation with Tom Houlden, though he hasn't reviewed anything I've written here

- [a la Ben Jones (2025) or Jones and Tonetti (2026), if references are useful]

- In the most extreme version, this would be R = min(L, C)

- (This notion of substitutability must be different from that discussed in the post / in the original AIFM model, but I don't follow what's going on there)

This didn't make much difference! Perhaps pushing things out two years. I thought this would be a crucial parameter (that is definitely the consensus among economists, see references above).

Which led me to investigate:

2. The shape of the automation function and the (exogenous) pace of compute growth seems to drive a lot

- Set beta = 1e12, so that there is zero algorithmic progress: constant S.

--> first equation of the model doesn't really matter at all - Not changing anything else

- That still gives 99% automation by 2045

I dunno how to think about the chosen automation function here, how to assess its plausibility. But seems important!

I think the crux vs papers like Jones and Tonetti (2026) is whether AI R&D is much easier to automate than tasks in the general economy. From a skim, they include AI increasing idea production but not specifically work at AI labs.

As for the shape of the automation curve, agree it's very important. I'd be interested in any ideas on how to measure it.

Thanks for doing some sensitivity analysis. It's often number one on my list of frustrating things not included in a model.

AIFM is extremely sensitive to time horizon in a way I wouldn't endorse.

- In particular, the "doubling difficulty growth factor", which measures whether time horizon increases superexponentially, could change the date of automated coder from 2028 to 2049!

You say that like it's a bad thing.

This sounds like the common implicit assumption that precise models are better.

Good models capture reality. Reality in this case seems highly uncertain.

It's possible for there to be irreducible uncertainty when modeling things, but AIFM is using time horizon to predict uplift / automation, and my claim is that we should collect data on uplift directly instead, which would bypass the poorly understood relationship between time horizon and uplift.

That does seem like it would be better. If you haven't done that yet, you need to keep the estimate in there with its wide uncertainty, right?

I actually do think parallel uplift is something like 1.4x-2.5x. This is just an educated guess but so are AIFM's credible intervals for time horizon trends. There's not really an empirical basis for AIF's guess that something like a 125 human-year time horizon AI will be just sufficient to automate all coding, nor that each time horizon doubling will be say 10% faster than the last. The uplift assumption naturally leads to narrower timelines uncertainty than the time horizon ones.

If and when we can prove something about uplift we'll hopefully publish more than a research note. At this point I would revisit the modeling assumptions too, and the end result may or may not be wide uncertainty. But you shouldn't just artificially make your confidence intervals wider because your all-things-considered view has wide uncertainty. More likely, a mismatch between them reflects factors you're not modeling, and you have to choose whether it's worth the cost to include them or not.

My point was that you mentioned removing a source of uncertainty in the model as though that's by default a good thing. The exclamation point on your mention of the wide uncertainty seems to imply that pretty strongly. I still don't know if you endorse that general attitude. I was not arguing that you shouldn't have removed that factor; I was arguing that you didn't argue for why removing it was good, but implied it was good anyway.

Perhaps this is a nitpick. But in my mind this point is about taking into account how your models are used and interpreted. It seems to me that precise models tend to cause overconfidence, so it would be wiser to err in the direction of including uncertainty in the models, rather than letting that uncertainty sit in complex grounding assumptions.

Naturally every model will have some of both.

In this post, I describe a simple model for forecasting when AI will automate AI development. It is based on the AI Futures model, but more understandable and robust, and has deliberately conservative assumptions.

At current rates of compute growth and algorithmic progress, this model's median prediction is >99% automation of AI R&D in late 2032. Most simulations result in a 1000x to 10,000,000x increase in AI efficiency and 300x-3000x research output by 2035. I therefore suspect that existing trends in compute growth and automation will still produce extremely powerful AI on "medium" timelines, even if the full coding automation and superhuman research taste that drive the AIFM's "fast" timelines (superintelligence by ~mid-2031) don't happen.

Why make this?

Scope and limitations

First, this model doesn't treat research taste and software engineering as separate skills/tasks. As such, I see it as making predictions about timelines (time to Automated Coder or Superhuman AI Researcher), not takeoff (the subsequent time from SAR to ASI and beyond). The AIFM can model takeoff because it has a second phase where the SAR's superhuman research taste causes further AI R&D acceleration on top of coding automation. If superhuman research taste makes AI development orders of magnitude more efficient, takeoff could be faster than this model predicts.

Second, this model, like AIFM, doesn't track effects on the broader economy that feed back into AI progress the way Epoch's GATE model does.

Third, we deliberately make two conservative assumptions:

This was constructed and written up fairly quickly (about 15 hours of work), so my opinions on parameters and some of the modeling assumptions could change in the future.

The model

We assume that AI development has the following dynamics:

This implies the following model:

S′(t)=R(t)S1−β=(L1−f)αCζS1−βf(t)=σ(v(log(C(t)S(t))−logEhac))where

None of the components of this model are novel to the AI forecasting literature, but I haven't seen them written up in this form.

Parameter values

The parameters are derived from these assumptions, which are basically educated guesses from other AI timelines models and asking around:

All parameters are independently distributed according to a triangular distribution. Due to the transforms performed to get alpha, zeta, and v, v will not be triangular and alpha and zeta will not be triangular or independent.

For more information see the notebook: https://github.com/tkwa/ai-takeoff-model/blob/main/takeoff_simulation.ipynb

Graphs

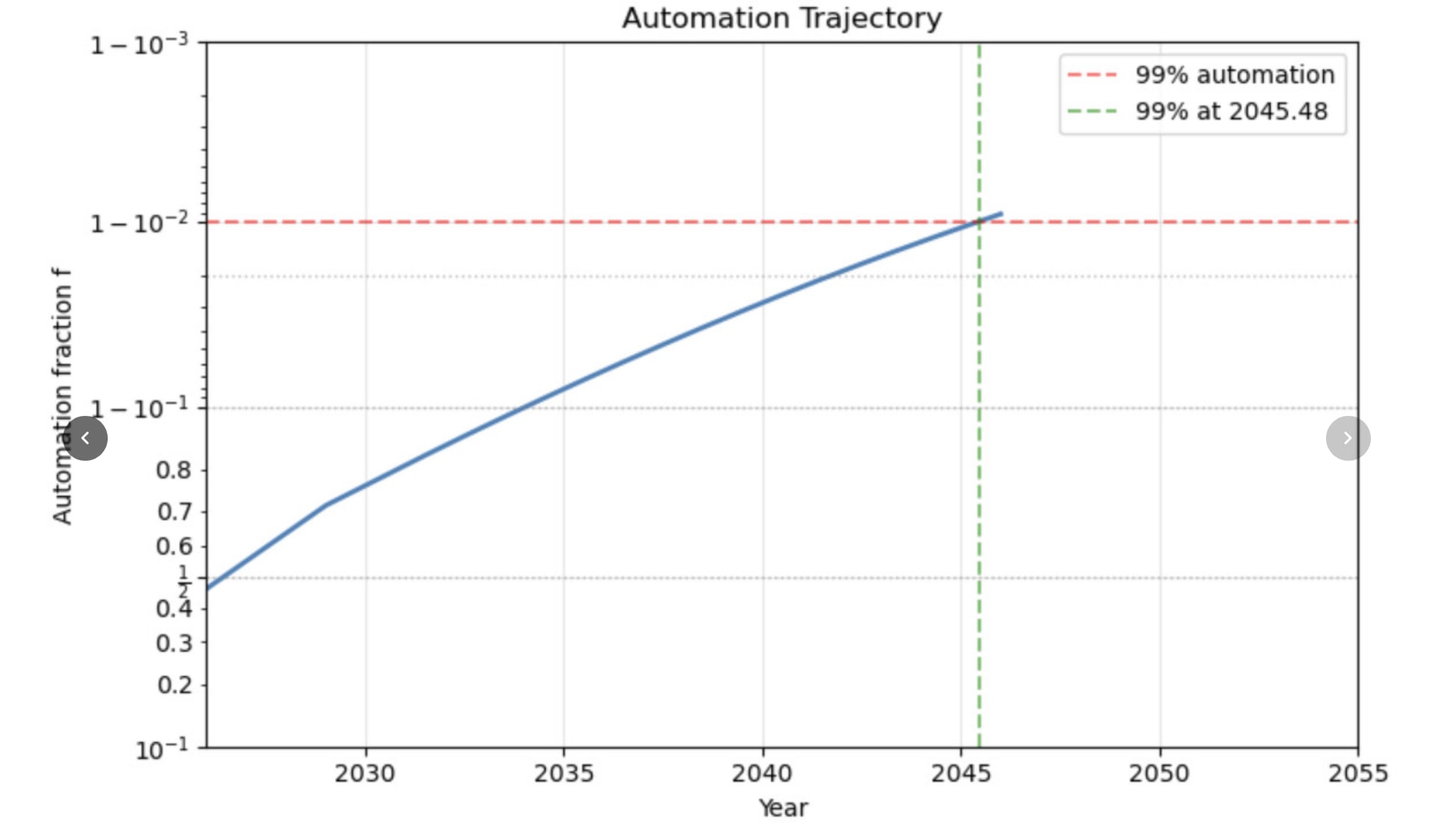

All graphs display 40 trajectories with parameters sampled according to the section Parameter Values.

Automation fraction f across the 40 trajectories (logit scale). Most trajectories reach 99% automation of AI R&D by the early-to-mid 2030s.

40 sampled trajectories of the model. Top left: software level S grows subexponentially (but very fast) as automation accelerates research. Top right: the parallel compute:labor ratio C/(L/(1−f)) (raw resource ratio before diminishing returns) decreases if automation is fast, but is ~constant if automation is on track for 99% by ~2034. Bottom left: research production R(t) increases by orders of magnitude. Bottom right: the serial compute:labor ratio Cζ/(L/(1−f))α (with diminishing returns exponents) trends upward. Trajectories are cut off at 99.9999% automation for numerical stability.

Sensitivity analysis: median year of 99% automation as a function of each parameter, with the other parameters sampled from their prior distributions. Higher beta (diminishing returns to software improvement) and higher 1/v (slower automation) delay 99% automation the most, while the other parameters have modest effects.

Observations

Discussion

From playing around with this and other variations to the AI Futures model I think any reasonable timelines model will predict superhuman AI researchers before 2036 unless AI progress hits a wall or is deliberately slowed.

In addition to refining the parameter values with empirical data, I would ideally want to backtest this model on data before 2026. However, a backtest is likely not feasible because automation was minimal before 2025, and automation of AI R&D is the main effect being modeled here.

More on modeling choices

List of differences from the AIFM

It may be useful to cross-reference this with my AIFM summary.

How could we better estimate the parameters?

We can get f(2026) [uplift fraction in 2026] from

v [velocity of automation as capabilities improve] can be obtained by

Why is automation logistic?

Why are labor and compute Cobb-Douglas?

In the AIFM, the median estimate for substitutability between labor and compute is -0.15, and the plausible range includes zero (which would be Cobb-Douglas). I asked Eli why they didn't just say it was Cobb-Douglas, and he said something like Cobb-Douglas giving infinite progress if one of labor/compute goes to infinity while the other remains constant, which is implausible. I have two responses to this:

Why is there no substitutability between tasks?

The AIFM's median was something like ρ=−2.0, meaning very weak substitution effects. To be conservative, I assumed no substitution effect.