[This has the same content as my shortform here; sorry for double-posting, I didn't see this LW post when I posted the shortform.]

Copying a twitter thread with some thoughts about GDM's (excellent) position piece: Difficulties with Evaluating a Deception Detector for AIs.

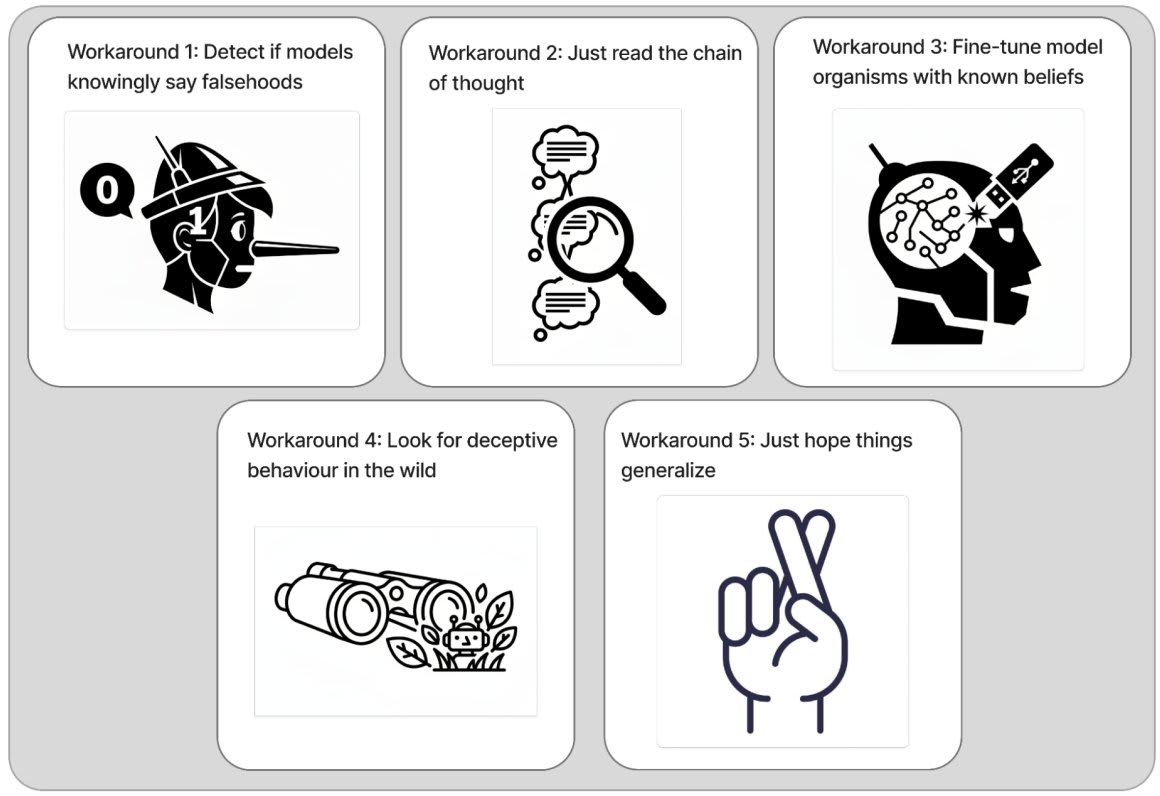

Research related to detecting AI deception has a bunch of footguns. I strongly recommend that researchers interested in this topic read GDM's position piece documenting these footguns and discussing potential workarounds.

More reactions in

-

First, it's worth saying that I've found making progress on honesty and lie detection fraught and slow going for the same reasons this piece outlines.

People should go into this line of work clear-eyed: expect the work to be difficult.

-

That said, I remain optimistic that this work is tractable. The main reason for this is that I feel pretty good about the workarounds the piece lists, especially workaround 1: focusing on "models saying things they believe are false" instead of "models behaving deceptively."

-

My reasoning:

1. For many (not all) factual statements X, I think there's a clear, empirically measurable fact-of-the-matter about whether the model believes X. See Slocum et al. for an example of how we'd try to establish this.

-

2. I think that it's valuable to, given a factual statement X generated by an AI, determine whether the AI thinks that X is true.

Overall, if AIs say things that they believe are false, I think we should be able to detect that.

-

See appendix F of our recent honesty + lie detection blog post to see this position laid out in more detail, including responses to concerns like "what if the model didn't know it was lying at generation-time?"

-

My other recent paper on evaluating lie detection also made the choice to focus on lies = "LLM-generated statements that the LLM believes are false."

(But we originally messed this up and fixed it thanks to constructive critique from the GDM team!)

-

Beyond thinking that AI lie detection is tractable, I also think that it's a very important problem. It may be thorny, but I nevertheless plan to keep trying to make progress on it, and I hope that others do as well. Just make sure you know what you're getting into!

In the paper, you repeatedly distinguish between a model actually having a set of beliefs and goals and possibly strategically deceptive behaviors, as opposed to roleplaying someone who has these.

For a human, this is a coherent concept with predictive power: they have a real persona, and may also have the acting skill to roleplay other personas. However, they will generally snap out of doing so under certain circumstances, including if the stakes get too high.

For a base model, this isn't a coherent concept: it doesn't have a single "real persona", it has a learned ability to simulate almost any token-generation process found on the internet. The only way it could meaningfully be said to be "roleplaying" is if it accurately simulated the persona of some human actor or author who was themselves roleplaying a separate different persona, in a way that meaningfully distinguished this from it just simulating the second persona — for example, if the actor was not a very good actor, or the author not a very good author, in such a way that the second persona was clearly fictional.

For an instruct-trained model, we have gone to some lengths to try to install the persona of a helpless, honest, and harmless assistant. However, it's unclear if this is now a "real" persona in the same sense that humans have one, such that any other persona is now automatically "roleplaying", or if the assistant is just a "high probability default persona", and under certain circumstances the model can still simulate other personas almost as fluidly as a base model can, without "roleplaying" them in any meaningful sense, and this behavior is just harder to elicit from an HHH model. So I think it's a non-trivial open question of whether "that's OK, it's just roleplaying as someone strategically deceptive, it isn't actually being someone strategically deceptive" is even a meaningful distinction for an HHH model or not, and if so when and to what extent it's true. Even if it was the case that the conversational turn "OK, you can stop roleplaying now" fairly reliable triggers a switch back to the default persona, I don't see that that actually proves that what was happening before that is more accurately modeled by "it's just roleplaying as someone strategically deceptive, it isn't actually being someone strategically deceptive". What actually matters from a safety point of view is whether the model would have spontaneously stopped "roleplaying" and reverted to its HHH persona if a high stakes situation cropped up, the way any (ethical) human actor would — and for a text based model, it correctly distinguishing an actual real high-stakes situation apart from a user roleplaying one as part of a work of fiction is a genuinely difficult problem, at least as hard as situational awareness. Similarly, coming up with a valid eval for this behavior without actually creating a real high-stakes situation is challenging for us.

For an previously HHH model that has then undergone further training of some sort to turn it into a model organism, it now has at least two "real personas", one attempting to overwrite the other, and this question then becomes even more challenging to resolve — it's even less like a (neurotypical) human.

So I think the question of "is the model actually being strategical deceptive, or just roleplaying someone strategically deceptive?" has a significant level of additional complexity beyond what you addressed in the paper — for an HHH model it's actually unclear to what degree that's even a meaningfully useful distinction or not. My default assumption for LLMs is that the instruct and alignment training tends to be a pretty thin layer over the underlying base model behavior, and for a base model, I think that that distinction is generally actively misleading. So I'd be rather cautious about applying this distinction to an HHH model (let along a model organism) — I'd first want to see a proof that it's (at least often) a meaningful distinction both in general, and in that specific context under consideration (since that could vary), and I think that's an inherently hard question to settle.

New research from the GDM mechanistic interpretability team. Read the full paper on arxiv or check out the twitter thread.