An Illustrated Summary of "Robust Agents Learn Causal World Model"

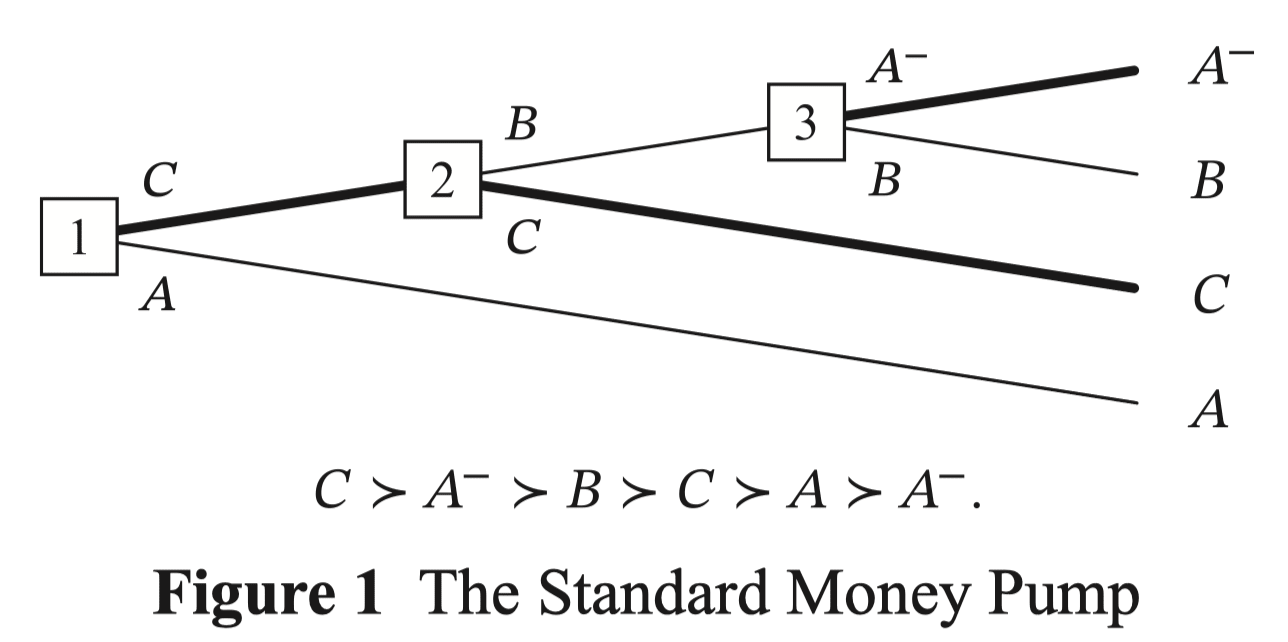

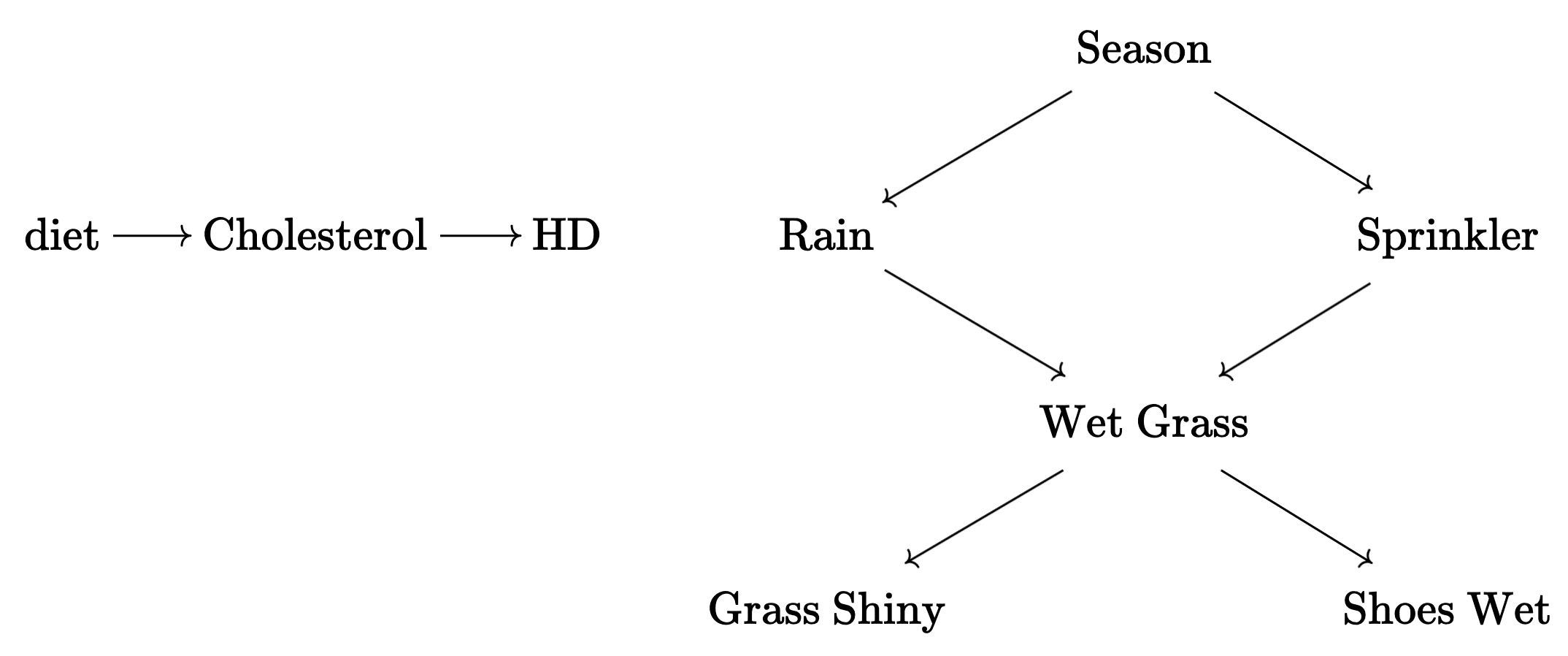

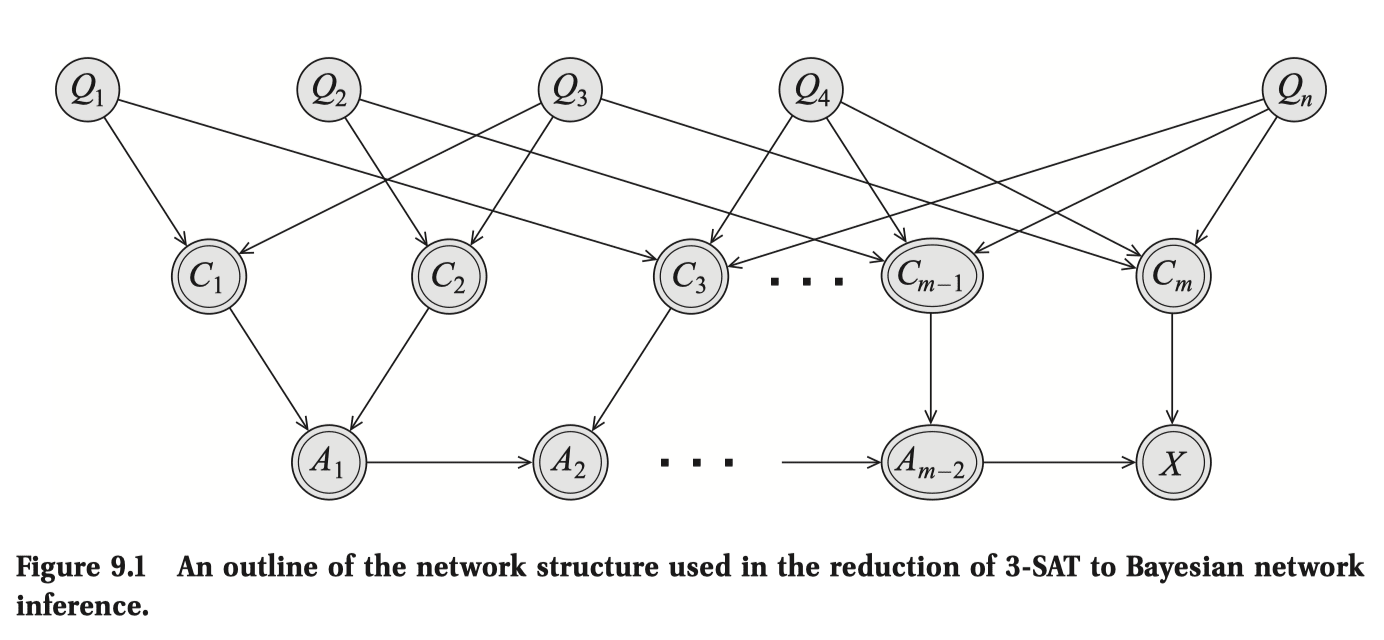

This post was written during Alex Altair's agent foundations fellowship program, funded by LTFF. Thank you Alex Altair, Alfred Harwood, Daniel C for feedback and comments. Introduction The selection theorems agenda aims to prove statements of the following form: "agents selected under criteria X has property Y," where Y are things such as world models, general purpose search, modularity, etc. We're going to focus on world models. But what is the intuition that makes us expect to be able to prove such things in the first place? Why expect world models? Because: assuming the world is a Causal Bayesian Network with the agent's actions corresponding to the D (decision) node, if its actions can robustly control the U (utility) node despite various "perturbations" in the world, then intuitively it must have learned the causal structure of how U's parents influence U in order to take them into account in its actions. And the same for the causal structure of how U's parents' parents influence U's parents ... and by induction, it must have further learned the causal structure of the entire world upstream of the utility variable. This is the intuitive argument that the paper Robust Agents Learn Causal World Model by Jonathan Richens and Tom Everitt formalizes. Informally, its main theorem can be translated as: if an agent responds to various environment interventions by prescribing policies that overall yield low regret, then it's possible to appropriately query the agent to reconstruct an implicit world model that matches up with the ground truth causal structure. I will refer to this result as the "Causal Good Regulator Theorem". This sequence Thoughts on the Causal Good Regulator Theorem will do the following: * [1] a precise statement of the theorem alongside a high-level argument of its proof and discussions of the paper's results in the context of the selection theorem agenda - basically a self-complete distillation of the paper. The rest of the posts in this

Plot idea: Isekaied from 2026 into some date in the past. Only goal: get cryogenically preserved into the glorious transhumanist singularity. How to influence the trajectory of history into a direction that would broadly enable this kind of future, while setting up the long-lasting infrastructure & incentives that would cryogenically preserve oneself for centuries to come?

I'm not going to write this, but I think this is a very interesting premise & problem (especially if thousands of years into the past) and would love to see someone build on it.

Some thoughts:

- It's definitely doable if it's to a century ago. The earliest cryopreserved human still preserved today is James Bedford, born in 1893 and

... (read 757 more words →)