What's your version of the story for how the "moderates" at OpenPhil ended up believing stuff even others can now see to be fucking nuts in retrospect and which "extremists" called out at the time, like "bio anchoring" in 2021 putting AGI in median fucking 2050, or Carlsmith's Multiple Stage Fallacy risk estimate of 5% that involved only an 80% chance anyone would even try to build agentic AI?

Were they no true moderates? How could anyone tell the difference in advance?

From my perspective, the story is that "moderates" are selected to believe nice-sounding moderate things, and Reality is off doing something else because it doesn't care about fitting in the same way. People who try to think like reality are then termed "extremist", because they don't fit into the nice consensus of people hanging out together and being agreeable about nonsense. Others may of course end up extremists for other reasons. It's not that everyone extreme is reality-driven, but that everyone who is getting pushed around by reality (instead of pleasant hanging-out forces like "AGI in 2050, 5% risk" as sounded very moderate to moderates before the ChatGPT Moment) ends up departing from ...

You can be a moderate by believing only moderate things. Or you can be a moderate by adopting moderate strategies. These are not necessarily the same thing.

This piece seems to be mostly advocating for the benefits of moderate strategies.

Your reply seems to mostly be criticizing moderate beliefs.

(My political beliefs are a ridiculous assortment of things, many of them outside the Overton window. If someone tells me their political beliefs are all moderate, I suspect them of being a sheep.

But my political strategies are moderate: I have voted for various parties' candidates at various times, depending on who seems worse lately. This seems...strategically correct to me?)

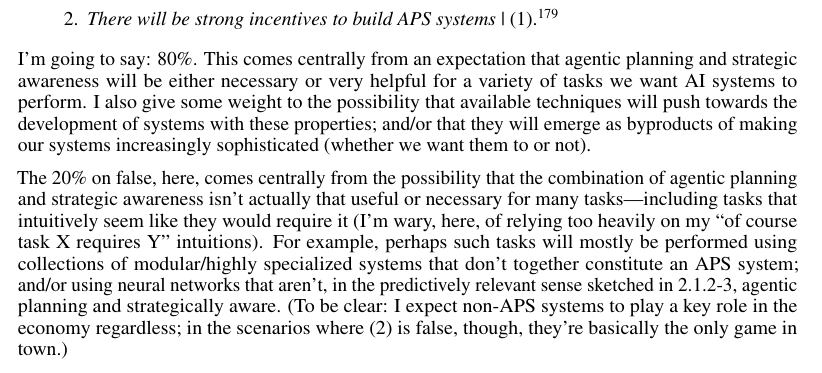

Carlsmith's Multiple Stage Fallacy risk estimate of 5% that involved only an 80% chance anyone would even try to build agentic AI?

This is false as stated. The report says:

The corresponding footnote 179 is:

As a reminder, APS systems are ones with: (a) Advanced capability: they outperform the best humans on some set of tasks which when performed at an advanced level grant significant power in today’s world (tasks like scientific research, business/military/political strategy, engineering, hacking, and social persuasion/manipulation); (b) Agentic planning: they make and execute plans, in pursuit of objectives, on the basis of models of the world; and (c) Strategic awareness: the models they use in making plans represent with reasonable accuracy the causal upshot of gaining and maintaining different forms of power over humans and the real-world environment.

Strong incentives isn't the same as "anyone would try to build" and "agentic AI" isn't the same as APS systems (which has a much more specific and stronger definition!).

I'd personally put more like 90% on the claim (and it might depend a lot on what you mean by strong incentives).

To be clear, I agree with the claim that Carlsmith's r...

I'd personally put more like 90% on the claim (and it might depend a lot on what you mean by strong incentives).

Are you talking in-retrospect? If you currently assign only 90% to this claim, I would be very happy to take your money (I would say a reasonable definition that I think Joe would have accepted at the time that we would be dealing with more than $1 billion in annual expenditure towards this goal).

I... actually have trouble imagining any definition that isn't already met, as people are clearly trying to do this right now. But like, still happy to take your money if you want to bet and ask some third-party to adjudicate.

Note that this post is arguing that there are some specific epistemic advantages of working as a moderate, not that moderates are always correct or that there aren't epistemic disadvantages to being a moderate. I don't think "there exist moderates which seem very incorrect to me" is a valid response to the post similarly to how "there exist radicals which seem very incorrect to me" wouldn't be a valid argument for the post.

This is independent from the point Buck notes that the label moderate as defined in the post doesn't apply in 2020.

As a response to the literal comment at top-of-thread, this is clearly reasonable. But I think Eliezer is correctly invoking some important subtext here, which your comment doesn't properly answer. (I think this because I often make a similar move to the one Eliezer is making, and have only understood within the past couple years what's load-bearing about it.)

Specifically, there's an important difference between:

- "<person> was wrong about <argument/prediction/etc>, so we should update downward on deferring to their arguments/predictions/etc", vs

- "<person> was wrong about <argument/prediction/etc>, in a way which seems blindingly obvious when we actually think about it, and so is strong evidence that <person> has some systematic problem in the methods they're using to think (as opposed to just being unlucky with this one argument/prediction/etc)"

Eliezer isn't saying the first one, he's saying the second one, and then following it up with a specific model of what is wrong with the thinking-methods in question. He's invoking bio anchors and that Carlsmith report as examples of systematically terrible thinking, i.e. thinking which is in some sense "obviously...

- "<person> was wrong about <argument/prediction/etc>, in a way which seems blindingly obvious when we actually think about it, and so is strong evidence that <person> has some systematic problem in the methods they're using to think (as opposed to just being unlucky with this one argument/prediction/etc)"

I think "this was blindingly obvious when we actually think about it", is not socially admissible evidence, because of hindsight bias.

I thought about a lot of this stuff before 2020. For the most part, I didn't reach definitive conclusions about a lot of it. In retrospect, a lot of the the conclusions that I did provisionally accept, I, in retrospect, think I was overconfident about, given the epistemic warrant.

Was I doing "actual thing"? No, probably not, or at least not by many relevant standards. Could I have done better? Surely, but not by recourse to magical "just think better" cognition.

The fact remains that It Was Not Obvious To Me.

Others may claim that it was obvious to them, and they might be right—maybe it was obvious to them.

If a person declared operationalized-enough-to-be-gradable prediction before the event was settled, well, then I can u...

Feels like there's some kind of frame-error here, like you're complaining that the move in question isn't using a particular interface, but the move isn't intended to use that interface in the first place? Can't quite put my finger on it, but I'll try to gesture in the right direction.

Consider ye olde philosophers who liked to throw around syllogisms. You and I can look at many of those syllogisms and be like "that's cute and clever and does not bind to reality at all, that's not how real-thinking works". But if we'd been around at the time, very plausibly we would not be able to recognize the failure; maybe we would not have been able to predict in advance that many of the philosophers' clever syllogisms totally fail to bind to reality.

Nonetheless, it is still useful and instructive to look at those syllogisms and say "look, these things obviously-in-some-sense do not bind to reality, they are not real-thinking, and therefore they are strong evidence that there is something systematically wrong with the thinking-methods of those philosophers". (Eliezer would probably reflexively follow that up with "so I should figure out what systematic thinking errors plagued those seemingly-bri...

So I guess maybe... Eliezer's imagined audience here is someone who has already noticed that bio anchors and the Carlsmith thing fail to bind to reality, but you're criticizing it for not instead responding to a hypothetical audience who thinks that the reports maybe do bind to reality?

I almost added a sentence at the end of my comment to the effect of...

"Either someone did that X was blindly obvious, in which case they don't need to be told, or it wasn't blindingly obvious to them, and they should should pay attention to the correct prediction, and ignore the assertion that it was obvious. In either case...the statement isn't doing anything?"

Who are statements like these for? Is it for the people who thought that things were obvious to find and identify each other?

To gesture at a concern I have (which I think is probably orthogonal to what you're pointing at):

On a first pass, the only people who might be influenced by statements like that are being influenced epistemically illegitimately.

Like, I'm imagining a person, Bob, who heard all the arguments at the time and did not feel confident enough to make a specific prediction. But then we all get to wait a fe...

Ok, I think one of the biggest disconnects here is that Eliezer is currently talking in hindsight about what we should learn from past events, and this is and should often be different from what most people could have learned at the time. Again, consider the syllogism example: just because you or I might have been fooled by it at the time does not mean we can't learn from the obvious-in-some-sense foolishness after the fact. The relevant kind of "obviousness" needs to include obviousness in hindsight for the move Eliezer is making to work, not necessarily obviousness in advance, though it does also need to "obvious" in advance in a different sense (more on that below).

Short handle: "It seems obvious in hindsight that <X> was foolish (not merely a sensible-but-incorrect prediction from insufficient data); why wasn't that obvious at the time, and what pattern do I need to be on the watch for to make it obvious in the future?"

Eliezer's application of that pattern to the case at hand goes:

- It seems obvious-in-some-sense in hindsight that bio anchors and the Carlsmith thing were foolish, i.e. one can read them and go "man this does seem kind of silly".

- Insofar as that wasn't obvious

The argument "there are specific epistemic advantages of working as a moderate" isn't just a claim about categories that everyone agrees exist, it's also a way of carving up the world. However, you can carve up the world in very misleading ways depending on how you lump different groups together. For example, if a post distinguished "people without crazy-sounding beliefs" from "people with crazy-sounding beliefs", the latter category would lump together truth-seeking nonconformists with actual crazy people. There's no easy way of figuring out which categories should be treated as useful vs useless but the evidence Eliezer cites does seem relevant.

On a more object level, my main critique of the post is that almost all of the bullet points are even more true of, say, working as a physicist. And so structurally speaking I don't know how to distinguish this post from one arguing "one advantage of looking for my keys closer to a streetlight is that there's more light!" I.e. it's hard to know the extent to which these benefits come specifically from focusing on less important things, and therefore are illusory, versus the extent to which you can decouple these benefits from the costs of being a "moderate".

It's not that moderates and radicals are trying to answer different questions (and the questions moderates are answering are epistemically easier like physics).

That seems totally wrong. Moderates are trying to answer questions like "what are some relatively cheap interventions that AI companies could implement to reduce risk assuming a low budget?" and "how can I cause AI companies to marginally increase that budget?" These questions are very different from—and much easier than—the ones the radicals are trying to answer, like "how can we radically change the governance of AI to prevent x-risk?"

I agree with this in principle, but think that doing a good job of noting major failings of prominent moderates in the current environment would look very different than Eliezer's comment and requires something stronger than just giving examples of some moderates which seem incorrect to Eliezer.

Another way to put this is that I think citing a small number of anecdotes in defense of a broader world view is a dangerous thing to do and not attaching this to the argument in the post is even more dangerous. I think it's more dangerous when the description of the anecdotes is sneering and misleading. So, when using this epistemically dangerous tool, I think there is a higher burden of doing a good job which isn't done here.

On the specifics here, I think Carlsmith's report is unrepresentative for a bunch of reasons. I think Bioanchors is representative (though I don't think it looks fucking nuts in retrospect).

This is putting aside the fact that this doesn't engage with the arguments in the post at all beyond effectively reacting to the title.

The bioanchors post was released in 2020. I really wish that you bothered to get basic facts right when being so derisive about people's work.

I also think it's bad manners for you to criticize other people for making clear predictions given that you didn't make such predictions publicly yourself.

I also think it's bad manners for you to criticize other people for making clear predictions given that you didn't make such predictions publicly yourself.

I generally agree with some critique in the space, but I think Eliezer went on the record pretty clearly thinking that the bio-anchors report had timelines that were quite a bit too long:

Eliezer: I consider naming particular years to be a cognitively harmful sort of activity; I have refrained from trying to translate my brain's native intuitions about this into probabilities, for fear that my verbalized probabilities will be stupider than my intuitions if I try to put weight on them. What feelings I do have, I worry may be unwise to voice; AGI timelines, in my own experience, are not great for one's mental health, and I worry that other people seem to have weaker immune systems than even my own. But I suppose I cannot but acknowledge that my outward behavior seems to reveal a distribution whose median seems to fall well before 2050.

I think in many cases such a critique would be justified, but like, IDK, I feel like in this case Eliezer has pretty clearly said things about his timelines expectations that co...

FWIW, I think it is correct for Eliezer to be derisive about these works, instead of just politely disagreeing.

Long story short, derision is an important negative signal that something should not be cooperated with. Couching words politely is inherently a weakening of that signal. See here for more details of my model.

I do know that this is beside the point you're making, but it feels to me like there is some resentment about that derision here.

My read is that the cooperation he is against is with the narrative that AI-risk is not that important (because it's too far away or whatever). This indeed influences which sorts of agencies get funded, which is a key thing he is upset about here.

Hm, I still don't really understand what it means to be [against cooperation with the narrative that AI risk is not that important]. Beyond just believing that AI risk is important and acting accordingly. (A position that seems easy to state explicitly.)

Also: The people whose work is being derided definitely don't agree with the narrative that "AI risk is not that important". (They are and were working full-time to reduce AI risk because they think it's extremely important.) If the derisiveness is being read as a signal that "AI risk is important" is a point of contention, then the derisiveness is misinforming people. Or if the derisiveness was supposed to communicate especially strong disapproval of any (mistaken) views that would directionally suggest that AI risk is less important than the author thinks: then that would just seems like soldier mindset (more harshly critizing views that push in directions you don't like, holding goodness-of-the-argument constant), which seems much more likely to muddy the epistemic waters than to send important signals.

This is not a response to your central point, but I feel like you somewhat unfairly criticize EAs for stuff like bioanchors often. You often say stuff that makes it seem like bioanchors was released, all EAs bought it wholesale, bioanchors shows we can be confident AI won't arrive before 2040 or something, and thus all EAs were convinced we don't need to worry much about AI for a few decades.

But like, I consider myself and EA, I never put much weight on bioanchors. I read the report and found it interesting, I think its useful enough (mostly as a datapoint for other arguments you might make) that I don't think was a waste of time. But not much more than that. It didn't really change my views on what should be done. Or the likelihood of AGI being developed at which points in time except on the margins. I mean thats how most people I know read that report. But I feel like you accuse people involved of having far less humility and masking way stronger stronger claims than they are.

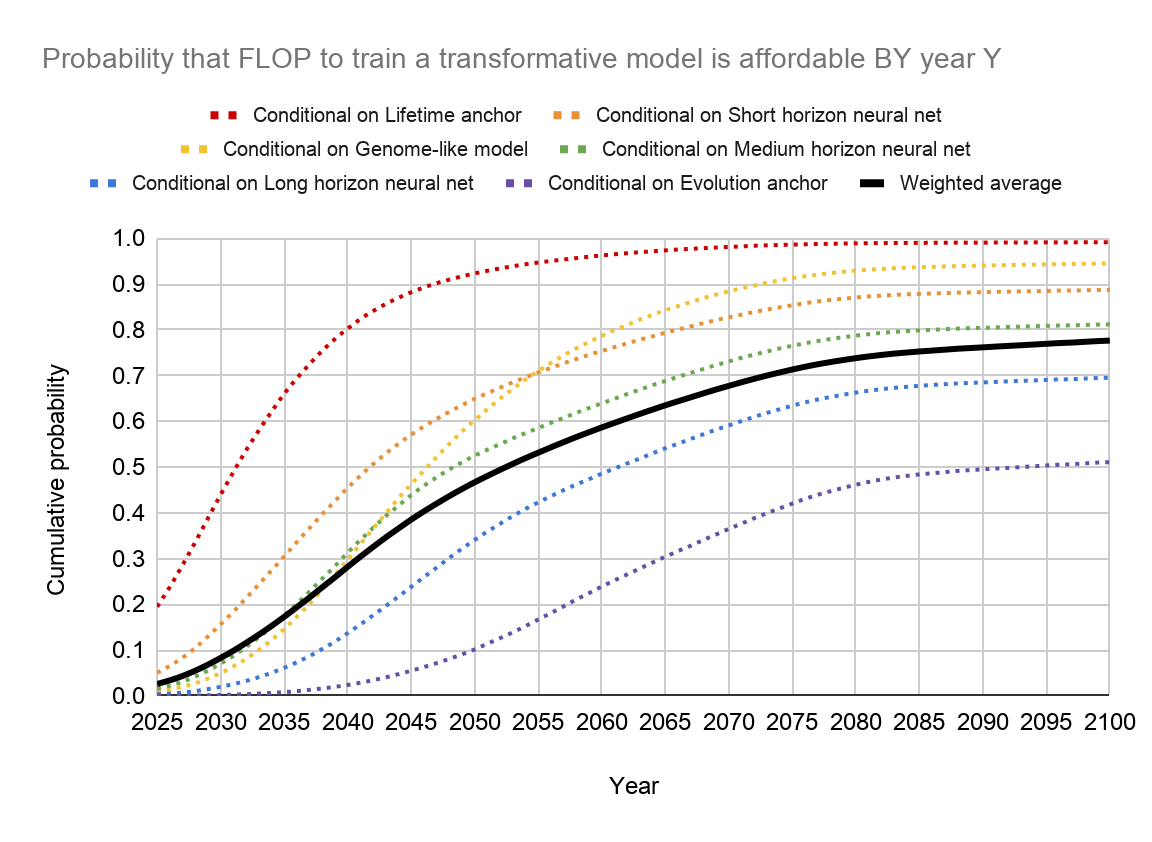

Notably, bioanchors doesn't say that we should be confident AI won't arrive before 2040! Here's Ajeya's distribution in the report (which was finished in about July 2020).

OpenPhil was on the board of CEA and fired it's Executive Director and to this day has never said why; it made demands about who was allowed to have power inside of the Atlas Fellowship and who was allowed to teach there; it would fund MIRI by 1/3rd the full amount for (explicitly stated) signaling reasons; in most cases it was not be open about why it would or wouldn't grant things (often even with grantees!) that left me just having to use my sense of 'fashion' to predict who would get grants and how much; I've heard rumors I put credence on that it wouldn't fund AI advocacy stuff in order to stay in the good books of the AI labs... there was really a lot of opaque politicking by OpenPhil, that would of course have a big effect on how people were comfortable behaving and thinking around AI!

It's silly to think that a politically controlling entity would have to punish ppl for stepping out of line with one particular thing, in order for people to conform on that particular thing. Many people will compliment a dictator's clothes even when he didn't specifically ask for that.

My guess is still that calling folks “moderates” and “radicals” rather some more specific name (perhaps “marginalists” and “reformers”) is a mistake and fits naturally into conversations about things it seems you didn’t want to be talking about.

Relatedly, calling a group of people 'radicals' seems straightforwardly out-grouping to me, I can't think of a time where I would be happy to be labeled a radical, so it feels a bit like tilting the playing field.

Agreed. Also, I think the word “radical” smuggles in assumptions about the risk, namely that it’s been overestimated. Like, I’d guess that few people would think of stopping AI as “radical” if it was widely agreed that it was about to kill everyone, regardless of how much immediate political change it required. Such that the term ends up connoting something like “an incorrect assessment of how bad the situation is.”

This is a good contribution (strong upvote), but this definition of 'moderate' also refers to not attempting to cause major changes within the company. Otherwise I think many of these points do not apply; within big companies if you want major change/reform you will often have to engage in some amount of coalitional politics, you will often have incentive to appear very confident, if your coalition is given a bunch of power then you often will not actually be forced to know a lot about a domain before you can start acting in it, etc.

I wonder if the distinction being drawn here is better captured by the names "Marginalists" vs "Revolutionaries".

In the leftist political sphere, this distinction is captured by the names "reformers" vs "revolutionaries", and the argument about which approach to take has been going on forever.

I believe it would be worthwhile for us to look at some of those arguments and see if previous thinkers have new (to us) perspectives that can be informative about AI safety approaches.

people in companies care about technical details so to be persuasive you will have to be familiar with them

Big changes within companies are typically bottlenecked much more by coalitional politics than knowledge of technical details.

I think one effect you're missing is that the big changes are precisely the ones that tend to mostly rely on factors that are hard to specify important technical details about. E.g. "should we move our headquarters to London" or "should we replace the CEO" or "should we change our mission statement" are mostly going to be driven by coalitional politics + high-level intuitions and arguments. Whereas "should we do X training run or Y training run" are more amenable to technical discussion, but also have less lasting effects.

Do you not think it's a problem that big-picture decisions can be blocked by a kind of overly-strong demand for rigor from people who are used to mostly think about technical details?

I sometimes notice something roughly like the following dynamic:

1. Person A is trying to make a big-picture claim (e.g. that ASI could lead to extinction) that cannot be argued for purely in terms of robust technical details (since we don't have ASI yet to run experiments, and don't have a theory yet),

2. Person B is more used to think about technical details that allow you to make robust but way more limited conclusions.

3. B finds some detail in A's argument that is unjustified or isn't exactly right, or even just might be wrong.

4. A thinks the detail really won't change the conclusion, and thinks this just misses the point, but doesn't want to spend time, because getting all the details exactly right would take maybe a decade.

5. B concludes A doesn't know what they're talking about and continues ignoring the big picture question completely and keeps focusing on more limited questions.

6. The issue ends up ignored.

It seems to me that this dynamic is part of the coalitional politics and how the high-level arguments are received?

I often hear people say that moderates end up too friendly to AI companies due to working with people from AI companies. I agree, but I think that working as a moderate has a huge advantage for your epistemics.

I think that this friendliness has its own very large epistemic effects. The better you know people, the more time you spend with them, and the friendlier you are with them, the more cognitive dissonance you have to overcome in order to see them as doing bad things, and especially to see them as bad people (in the sense of their actions being net harmful for the world). This seems like the most fundamental force behind regulatory capture (although of course there are other factors there like the prospect of later getting industry jobs).

You may be meaning to implicitly recognize this dynamic in the quote above; it's not clear to me either way. But I think it's worth explicitly calling out as having a strong countervailing epistemic impact. I'm sure it varies significantly across people (maybe it's roughly proportional to agreeability in the OCEAN sense?), and it may not have a large impact on you personally, but for people to weigh the epistemic value of working as a moderate, it's important that they consider this effect.

I think it's pretty bizarre that despite the fact that LessWrongers are usually acutely aware of the epistemic downsides of being an activist, they seem to have paid relatively little attention to this in their recent transition to activism.

FWIW I'm the primary organizer of PauseAI UK and I've thought about this a lot.

I spend lots of time talking to and aiming to persuade AI company staff

Has this succeeded? And if so, do you have specific, concrete examples you can speak about publicly that illustrate this?

Mostly AI companies researching AI control and planning to some extent to adopt it (e.g. see the GDM safety plan).

I doubt this is what Buck had in mind, but he's had meaningful influence on the various ways I've changed my views on the big picture of interp over time

Seems like a huge point here is ability to speak unfiltered about AI companies? The Radicals working outside of AI labs would be free to speak candidly while the Moderates would have some kind of relationship to maintain.

I agree this is a real thing.

Note that this is more important for group epistemics than individual epistemics.

Also, one reason the constraint isn't that bad for me is that I can and do say spicy stuff privately, including in pretty large private groups. (And you can get away with fairly spicy stuff stated publicly.)

Radicals often seem to think of AI companies as faceless bogeymen thoughtlessly lumbering towards the destruction of the world. I

This strikes me as a fairly strong strawman. My guess if the vast majority of thoughtful radicals basically have a similar view to you. Indeed, at least from your description, its plausible my view is more charitable than yours - I think a lot of it is also endangering humanity due to cowardice and following of local incentives etc.

Most of the spicy things I say can be said privately to just the people who need to hear them, freeing me from thinking about the implications of random third parties reading my writing.

Isn't this a disadvantage? If third-parties that disagree with you, were able to criticize spicy things you say, and possibly counter-persuade people from AI companies, you would have to be even more careful.

In this post, I mostly conflated "being a moderate" with "working with people at AI companies". You could in principle be a moderate and work to impose extremely moderate regulations, or push for minor changes to the behavior of governments.

Note that I think something like this describes a lot of people working in AI risk policy, and therefore seems like more than a theoretical possibility.

...The main advantage for epistemics of working as a moderate is that almost all of your work has an informed, intelligent, thoughtful audience. I spend lots of time talking to and aiming to persuade AI company staff who are generally very intelligent, knowledgeable about AI, and intimately familiar with the goings-on at AI companies. In contrast, as a radical, almost all of your audience—policymakers, elites, the general public—is poorly informed, only able or willing to engage shallowly, and needs to have their attention grabbed intentionally. The former si

I think looking for immediately-applicable changes which are relevant to concrete things that people at companies are doing today need not constrain you to small changes, and so I would not use the words you're using, since they seem like a bad basis space for talking about the moving parts involved. I agree that people who want larger changes would get better feedback, and end up with more actionable plans, if they think in terms of what change is actually implementable using the parts available at hand to people who are thinking on the frontier of making things happen.

I really like this post.

In this post, I mostly conflated "being a moderate" with "working with people at AI companies". You could in principle be a moderate and work to impose extremely moderate regulations, or push for minor changes to the behavior of governments.

There's also a "moderates vs radicals" when it comes to attitudes, certainty in one's assumptions, and epistemics, rather than (currently-)favored policies. While some of the benefits you list are hard to get for people who are putting their weight behind interventions to bring about radical chan...

I think there is a fair amount of overlap between the epistemic advantages of being a moderate (seeking incremental change from AI companies) and the epistemic disadvantages.

Many of the epistemic advantages come from being more grounded or having tighter feedback loops. If you're trying to do the moderate reformer thing, you need to justify yourself to well-informed people who work at AI companies, you'll get pushback from them, you're trying to get through to them.

But those feedback loops are with that reality as interpreted by people at AI companies. So,...

I think that to many in AI labs, the control agenda (in full ambition) is seen as radical (it's all relative) and to best persuade people that it's worth pursuing rigorously, you do in fact need to engage in coalitional politics and anything else that increases your chances of persuasion. The fact that you feel like your current path doesn't imply doing this makes me more pessimistic about your success.

This is an anonymous account but I've met you several times and seen you in action at AI policy events, and I think those data points confirm my view above.

Curated, this helpfully pointed out some important dynamics in the discourse that I think are present but have never been quite made explicit. As per the epistemic notice, I think this post was likely quickly written and isn't intended to reflect the platonic ideal set of points on this, but I stand behind it as being illuminating on an important subject and worth sharing.

I want to pull out one particular benefit that I think swamps the rest of the benefits, and in particular explains why I tend to gravitate to moderation over extremism/radicalism:

Because I'm trying to make changes on the margin, details of the current situation are much more interesting to me. In contrast, radicals don't really care about e.g. the different ways that corporate politics affects AI safety interventions at different AI companies.

Caring about the real world details of a problem is often quite important in devising a good solution, and is argua...

Thanks for writing this. I’m not sure I’d call your beliefs moderate, since they involve extracting useful labor from misaligned AI by making deals with them, sometimes for pieces of the observable universe or by verifying with future tech.

On the point of “talking to AI companies”, I think this would be a healthy part of any attempted change although I see that PauseAI and other orgs tend to talk to AI companies in a way that seems to try to make them feel bad by directly stating that what they are doing is wrong. Maybe the line here is “You make sur...

Very glad of this post. Thanks for broaching, Buck.

Status: I'm an old nerd, lately ML R&D, who dropped career and changed wheelhouse to volunteer at Pause AI.

Two comments on the OP:

details of the current situation are much more interesting to me. In contrast, radicals don't really care about e.g. the different ways that corporate politics affects AI safety interventions at different AI companies.

As per Joseph's response: this does not match me or my general experience of AI safety activism.

Concretely, a recent campaign was specifically about Deep M...

I think there might be a confusion between optimizing for an instrumental vs. an upper-level goal. Is maintaining good epistemics more relevant than working on the right topic? To me the rigor of an inquiry seems secondary to choosing the right subject.

Consider the following numbered points:

-

In an important sense, other people (and culture) characterize me as perhaps moderate (or something else). I could be right, wrong, anything in between, or not even wrong. I get labeled largely based on what others think and say of me.

-

How do I decide on my policy positions? One could make a pretty compelling argument (from rationality, broadly speaking) that my best assessments of the world should determine my policy positions.

-

Therefore, to the extent I do a good job of #2, I should end up recommending polici

[epistemic status: the points I make are IMO real and important, but there are also various counterpoints; I'm not settled on an overall opinion here, and the categories I draw are probably kind of dumb/misleading]

Many people who are concerned about existential risk from AI spend their time advocating for radical changes to how AI is handled. Most notably, they advocate for costly restrictions on how AI is developed now and in the future, e.g. the Pause AI people or the MIRI people. In contrast, I spend most of my time thinking about relatively cheap interventions that AI companies could implement to reduce risk assuming a low budget, and about how to cause AI companies to marginally increase that budget. I'll use the words "radicals" and "moderates" to refer to these two clusters of people/strategies. In this post, I’ll discuss the effect of being a radical or a moderate on your epistemics.

I don’t necessarily disagree with radicals, and most of the disagreement is unrelated to the topic of this post; see footnote for more on this.[1]

I often hear people claim that being a radical is better for your epistemics than being a moderate: in particular, I often hear people say that moderates end up too friendly to AI companies due to working with people from AI companies. I agree, but I think that working as a moderate has a huge advantage for your epistemics.

The main advantage for epistemics of working as a moderate is that almost all of your work has an informed, intelligent, thoughtful audience. I spend lots of time talking to and aiming to persuade AI company staff who are generally very intelligent, knowledgeable about AI, and intimately familiar with the goings-on at AI companies. In contrast, as a radical, almost all of your audience—policymakers, elites, the general public—is poorly informed, only able or willing to engage shallowly, and needs to have their attention grabbed intentionally. The former situation is obviously way more conducive to maintaining good epistemics.

I think working as a moderate has a bunch of good effects on me:

Many people I know who work on radical AI advocacy spend almost all their time thinking about what is persuasive and attention-grabbing for an uninformed audience. They don't experience nearly as much pressure on a day-to-day basis to be well informed about AI, to understand the fine points of their arguments, or to be calibrated and careful in their statements. They update way less on the situation from their day-to-day work than I do. They spend their time as big fish in a small pond.

I think this effect is pretty big. People who work on radical policy change often seem to me to be disconnected from reality and sloppy with their thinking; to engage as soldiers for their side of an argument, enthusiastically repeating their slogans. I think it's pretty bizarre that despite the fact that LessWrongers are usually acutely aware of the epistemic downsides of being an activist, they seem to have paid relatively little attention to this in their recent transition to activism. Given that radical activism both seems very promising and is popular among LessWrongers regardless of what I think about it, I hope we try to understand the risks (perhaps by thinking about historical analogies) of activism and think proactively and with humility about how to mitigate them.

I'll note again that the epistemic advantages of working as a moderate aren’t in themselves strong reasons to believe that moderates are right about their overall strategy.

I will also note that I work as a moderate from outside AI companies; I believe that working inside AI companies carries substantial risks for your epistemics. But IMO the risks from working at a company are worth conceptually distinguishing from the risks resulting from working towards companies adopting marginal changes.

In this post, I mostly conflated "being a moderate" with "working with people at AI companies". You could in principle be a moderate and work to impose extremely moderate regulations, or push for minor changes to the behavior of governments. I did this conflation mostly because I think that for small and inexpensive actions, you're usually better off trying to make them happen by talking to companies or other actors directly (e.g. starting a non-profit to do the project) rather than trying to persuade uninformed people to make them happen. And cases where you push for minor changes to the behavior of governments have many of the advantages I described here: you're doing work that substantially involves understanding a topic (e.g. the inner workings of the USG) that your interlocutors also understand well, and you spend a lot of your time responding to well-informed objections about the costs and benefits of some intervention.

Thanks to Daniel Filan for helpful comments.

Some of our difference in strategy is just specialization: I’m excited for many radical projects, some of my best friends work on them, and I can imagine myself working on them in the future. I work as a moderate mostly because I (and Redwood) have comparative advantage for it: I like thinking in detail about countermeasures, and engaging in detailed arguments with well-informed but skeptical audiences about threat models.

And most of the rest of the difference in strategy between me and radicals is downstream of genuine object-level disagreement about AI risks and how promising different interventions are. If you think that all the interventions I'm excited for are useless, then obviously you shouldn't spend your time advocating for them.