Rejected for the following reason(s):

- No LLM generated, heavily assisted/co-written, or otherwise reliant work.

- LessWrong has a particularly high bar for content from new users and this contribution doesn't quite meet the bar.

Read full explanation

Rejected for the following reason(s):

By Felipe Florez.

Dedicated to my parents; everything started with them

Preface

Dear reader.

Reason is better than no-Reason.

Morality is objective.

When we act wrong, we fail. When we allow evil to happen, we fail. We are not perfect, but we can be better.

In any world where vulnerable beings interact and follow rational strategies, the only stable and coherent moral system is based on Moral Objectivity preventing harm on sentient vulnerable beings.

This argument binds even a God.

Declaration of advanced language models:This post was developed in collaboration with an AI language model. The conceptual framework, arguments, claims, and conclusions are entirely my own; the model assisted only with drafting and organization. All responsibility for the ideas presented here lies with me. Any errors, omissions, or controversial positions are mine alone. The purpose of using an LLM was to accelerate writing, not to generate reasoning or substitute for human judgement.

Abstract

Binding God: Why Objective Morality is the Only Way develops a formal argument for objective morality grounded not in cultural norms, metaphysical assumptions, or divine authority, but in the universal structure of sentient existence. The argument proceeds from a minimal and uncontroversial premise: all sentient beings are vulnerable to harm. From this fact, and from the public-reason constraints that define what counts as a moral claim, it is shown that any coherent moral system must account for vulnerability and cannot treat harm as morally irrelevant. A morality that ignores harm collapses into incoherence by failing to guide creatures whose agency depends on their ability to be harmed or helped. The paper demonstrates—through transcendental analysis, game-theoretic confirmation, and the rejection of rival frameworks—that the systematic prevention of unnecessary harm is the only possible objective foundation of morality. This leads to two inevitable principles: a negative constraint against inflicting unjustified harm, and a positive duty to reduce preventable suffering within the limits of rational agency. The result is a unified, non-arbitrary moral framework that applies to all sentient beings and clarifies the structure of rights, justice, responsibility, and moral progress. No alternative foundation survives universal scrutiny. The harm-minimizing system is not only normatively compelling—it is the only coherent morality possible.

Introduction

Descartes initiated, but I concluded. This text pretends to be the foundation of Moral Objectivity basing the affirmation not in metaphysics, divine wills or cultural preferences. Instead, it shows a clear and unescapable deduction that defines a principle able to bind even an omniscient super-entity.

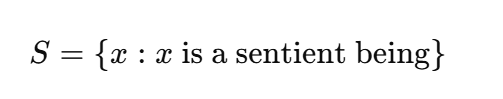

We are going to start with an undeniable fact of our universe: All sentient beings share one universal, mind-independent property:

Vulnerability to harm.

This simple fact, often overlooked or treated as trivial, turns out to be the foundation of all coherent moral reasoning. Any moral principle, precept or normative must address this fact to be rationally coherent. In a system where the rules ignore harm cannot distinguish torture from kindness and collapses into incoherence (basically, it leads to self-destruction)

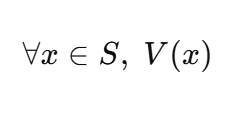

In order to preserve and honor Reason, the essay introduces four normative-structural axioms that define what counts as a moral rule:

These axioms are not optional values; they are preconditions for a system to function as a moral system at all. They are the first conditions before all other conditions.

The Central Derivation

From these axioms, one unique principle emerges:

Harm is morally negative unless justified by consent or the prevention of greater harm.

This yields the main theorem of the manuscript:

An action is morally wrong exactly when it harms someone without consent and without preventing something worse.

This framework is objective because it follows necessarily from mind-independent facts and constitutive rational constraints.

Game-Theoretic Confirmation

This principle is so deep that it cannot be questioned even though the precision and contingency of Math and Logic. IIndependent analysis using game theory shows:

Thus, the harm-minimizing system is not merely philosophically coherent—it is the only stable strategy set in rational multi-agent environments, according to Game Theory results..

This framework:

Once vulnerability is acknowledged and moral reasons must be public, the Pillars Principle becomes the only coherent morality possible. Every alternative fails under logical, normative, or game-theoretic analysis. This manuscript demonstrates the inevitability of this result. There is no coherent escape.

Objective morality exists.It is grounded on vulnerability. It is the systematic prevention of unnecessary harm in order to make Reason possible.

Part I: The Problem and the Starting Point

1.1. The Problem of Moral Objectivity

Descartes deducted:

“Cogito, ergo sum”

I didn't stop deducing. He did.

“Sum, ergo protego”

Every society since the beginning of time has rules about how we should treat one another. Yet across history and across cultures, people have disagreed about why those rules matter, what they should be, and whether any of them are truly universal. Even in the presence of normative coincidences all over history and cultures, people deny that Evil is more than a preference, a choice. This is the heart of one of philosophy’s oldest questions: Can morality be objective?

Two broad views dominate this debate.

On one side is moral realism, the idea that some moral truths exist independently of personal taste or cultural custom. According to realists, statements like “it is wrong to torture a child for fun” are not opinions the way “vanilla ice cream is better than chocolate” is an opinion. Instead, they reflect something deeper and more stable — a truth we can recognize regardless of where we were born.

On the other side is moral relativism, which sees moral rules as products of culture, upbringing, or individual preference. From this perspective, moral standards are more like social agreements: useful, flexible, and shaped by context, but without any claim to universal truth. What one group sees as virtuous, another may see as forbidden — and there is no higher standpoint that can settle the disagreement.

Between these two positions lies a persistent metaethical challenge:

If moral principles vary, and if people justify them in different ways, is it even possible to claim that morality has an objective and undeniablefoundation? And even if such a foundation existed, could it really be one foundation — a single principle capable of grounding all moral reasoning across times, cultures, and circumstances?

This question has haunted philosophers for centuries. Many arguments for objectivity end up assuming what they try to prove. Others collapse under the weight of cultural disagreement. Yet most of us, in our everyday lives, behave as some actions really are wrong no matter who commits them. There are real consequences on sentient beings’ agency derived from phenomena.

This dilema — between disagreement and the intuition of universality — is what this essay aims to address.

1.2. The Starting Point: The Human Condition

To search for an objective foundation of morality, we must begin somewhere simple, something we all share before culture, laws, or beliefs come into play. Not an opinion not a preference, not faith. Fortunately, we do not need to look far.

Every human being is vulnerable.

We can be hurt.

We can be threatened.

We can fall ill, suffer loss, and ultimately, die.

This is not a matter of opinion or tradition; it is a biological and existential reality. Kings and beggars, ancient farmers and modern workers, people from every continent and every time all live under the same condition of being able to suffer harm. And this condition is not unique to humans. Every sentient creature that can feel pain, fear, or distress inhabits the same fragile space of vulnerability. Animals, too, can be wounded, frightened, and deprived of the conditions that allow them to live well. Every person who has shared love and time with a pet would be outraged by the mere mention of the possibility that their loved animal companions are not subject to cold, heat, hunger or thirst.

Because of this, many of the moral imperatives we apply to humans extend naturally to animals. The logic is the same: if a being can be harmed, then its interests matter in some moral sense. While humans and animals differ in countless ways — in language, in culture, in levels of self-awareness — these differences do not erase the shared foundation of sentience. A creature that can suffer provides, by that very fact, a reason to avoid inflicting unnecessary harm upon it.

Thus, the structure of vulnerability reaches beyond our species. It forms a broader circle of moral consideration grounded not in human exceptionalism, but in the simple capacity to be harmed or helped. Any ethical system that claims to deal with right and wrong must grapple with this fact: wherever there is suffering, there is at least the potential for a moral obligation.

This does not mean that all duties toward animals are identical to those we hold toward humans. But it does mean that the basic insight on which morality stands ( the recognition of harm and the imperative to avoid causing it without necessity) is not limited to human relationships alone. It emerges from the shared condition of all sentient life.

Because this vulnerability is universal, morality must create a set of constraints on how we can reason ethically. Any system that completely ignores human frailty fails before it even begins. A morality that encourages unnecessary harm, or that pays no attention to the conditions that allow agency of life, cannot seriously be called a moral system at all.

This is where our inquiry starts taking shape..

If morality is meant to guide how we treat one another, and if all people share the same basic exposure to harm, then perhaps the foundation we are looking for is not hidden in cultural codes or divine commands, but in the structure of the sentience condition itself.

From this perspective, the question of moral objectivity becomes intertwined with a simple insight:

Whatever morality is, it must make sense for beings who can be harmed, who can be protected, and who depend on one another to live and thrive. This insight does not solve the problem yet. But it gives us a solid ground from which to build a sentient ground, shared by all, and free of cultural assumptions.

Moral principles, however, do not extend to everything that exists. They do not apply to rocks, rivers, stars, or machines that lack sensation. The reason is straightforward: morality concerns how our actions affect beings who can be harmed or benefited. A stone cannot suffer. A mountain does not experience fear. An unconscious object has no interests to protect, no well-being to preserve, and no inner life that can be damaged. Because of this, there is no meaningful sense in which we can wrong a rock or violate the “rights” of a chair. Ethical responsibilities emerge only where there is the capacity for harm where experience, however simple or complex, can be improved or worsened. Therefore, while morality extends widely across the domain of sentient life, it does not apply to the vast, insentient world that cannot be harmed in any morally relevant way.

1.3. Moral Reasoning Begins With Vulnerability to Harm

Morality must address the vulnerability of Reason. Otherwise, the moral principle falls into nothingness. How can we possibly have certainty of this? Human vulnerability gives us the first answer. Animal vulnerability extends it. And the absence of vulnerability in insentient objects limits it. The pattern is unmistakable: morality tracks the capacity to be harmed.

So::

Moral principles arise in response to beings who can be harmed, supported, protected, or destroyed.

If something cannot suffer or be deprived of anything meaningful (like a stone, a river, or a fictional character) then moral categories simply do not apply. We do not wrong a chair by breaking it, nor do we commit a moral transgression by reshaping a landscape.

And even in cases where we alter a river’s flow or contaminate its waters, the moral concern does not arise because the river itself is harmed — a river does not feel pain, fear, or loss. The wrongness comes from the consequences such actions have on the beings who can be harmed: the animals that depend on the river, the humans who drink from it, the ecosystems whose life unfolds around it. In other words, the moral weight lies not in damage to insentient objects but in the ripple effects on sentient creatures.

This does not yet tell us what the foundation of morality is. But it tells us where the foundation cannot be: it cannot be in tradition, in divine commands without justification, or in rules detached from the reality of lived experience. It must be founded on what is universally true of the beings to whom morality applies.

And what is universally true of them is simple:

They can be harmed.

This is the starting point from which we can build the argument that preventing unnecessary harm is not only a powerful moral principle, but the objective foundation of morality itself.

Before we can create a complete moral theory, we must first establish the conceptual foundations that make objective morality possible at all. This section builds the formal structure, step by step, so everything that follows stands on unshakable ground

To show that morality has an objective foundation, we must move carefully and deliberately. The argument cannot rely on assumptions about culture, religion, or personal taste. It must begin with facts that no reasonable person can deny, and from those facts, build toward a conclusion that follows naturally.

The structure of the argument is simple, but powerful. It unfolds in three steps:

1.3.1. Identify the universal condition shared by all beings to whom morality applies. This is the fact of vulnerability, the capacity to be harmed, to suffer, or to have one’s life made worse.

1.3.2. Show that any ethical system must account for this condition. A moral framework that ignores harm, or that treats deliberate suffering as irrelevant, cannot guide creatures whose lives are shaped by their ability to be damaged.

1.3.3. Demonstrate that this shared condition generates a universal objective moral requirement. Because all sentient beings can be harmed, and because harm undermines the very possibility of living well, preventing unnecessary harm becomes the most basic and objective demand of ethical reasoning.

These steps lead to a conclusion that is both intuitive and philosophically sound: Morality is not grounded in custom, authority, or preference; it is grounded in what it means to be a being capable of harm.

To support this conclusion, the essay advances a set of premises, each building directly on the last, that together establish the objectivity of morality’s foundation. These premises form the backbone of the argument:

This is the architecture of the argument. What follows is a careful examination of each premise, showing how they connect and why they support the conclusion that preventing unnecessary harm is the objective basis of morality.

Part II. The Architecture of the Argument

2.1. Premise 1 — The Universality of Vulnerability

Every moral system, whether ancient or modern, spiritual or secular, deals with the same basic reality: the beings it regulates can be harmed. This is not a cultural detail or a historical accident,it is a condition written into the very structure of life.

Human beings bleed, break, weaken, and suffer. Our bodies can be injured; our minds can be distressed; our well-being can be undermined by force, neglect, or betrayal. This fragility is not optional, and it is not something we outgrow. It accompanies us from birth to death, binding us to one another in a shared dependence on protection and care.

But this vulnerability is not ours alone. Animals, too, feel fear, pain, deprivation, and distress. Their reactions to harm are not symbolic or imagined; they are physiological and experiential. The same blow that injures a person injures a dog. The same starvation that weakens a human weakens a horse. And at a more fundamental level, the urge to avoid harm and to seek safety is a universal feature of sentient life.

This shared vulnerability forms the first pillar of the argument. It gives us a starting point that is both factual and universal. No matter where one lives, what language one speaks, or what beliefs one holds, it remains true that beings who can experience suffering require some form of protection if they are to live well.

By contrast, entities without sensation (stones, rivers, machines, abstract ideas) possess no such vulnerability. They cannot be harmed in any morally relevant sense because nothing is experienced as loss or pain. We may damage or destroy these objects, but we do not injure them. Their “destruction” becomes morally concerning only when it indirectly affects beings capable of harm: when a polluted river poisons animals, or a collapsed building injures the people inside.

Thus, the universality of vulnerability is not merely a biological fact; it is the foundation that makes moral discussion possible. It is the common thread linking all beings to whom morality can meaningfully apply. Without vulnerability, there is nothing to protect, nothing to respect, and nothing that can be wronged.

Morality must speak about what we should or should not do, it must speak about harm. And if it speaks about harm, it must begin with the beings who can actually be harmed. This is the starting point from which objective morality can be drawn, not from opinion or preference, but from the shared condition of sentience itself.

2.2. Premise 2 — Ethical Reasoning Must Account for Vulnerability

If ethical reasoning is meant to guide how we treat one another, then it must take seriously the nature of the beings involved. A set of rules that ignores what we are cannot meaningfully tell us what we ought to do.

Creatures who can be harmed require protection; creatures who cannot be harmed do not. This simple fact places a structural demand on any moral framework: it must consider the effects of actions on beings capable of suffering or benefit. Without this, moral guidance becomes detached from reality.

Take an ethical system that claims to be indifferent to harm. Suppose it says that causing pain is neither right nor wrong, that destroying well-being carries no moral weight. What would such a system imply? It would permit torture, cruelty, negligence, or extermination without any moral hesitation. It would render unjustified suffering morally invisible.

That is not moral at all.

But this leads to an immediate contradiction: if the system’s purpose is to guide the lives of sentient beings (beings whose experience can be improved or worsened) then a framework that ignores harm fails them at the most basic level. It becomes unfit for the very creatures it seeks to regulate.

Moral reasoning cannot sensibly classify murder, starvation, deceit, or abandonment as neutral actions, because these acts directly affect the vulnerable structure of sentient life. Likewise, it cannot treat kindness, protection, and care as morally irrelevant, because these actions interact with the same structure in the opposite direction, they reduce harm and support flourishing.

The convergence of moral principles (especially prohibitions against cruelty) is not the result of mysticism or metaphysical coincidence. It is an evolutionary and social necessity. Human communities that failed to restrain unnecessary harm could not sustain the trust, reciprocity, or long-term cooperation required for survival. Groups that tolerated cruelty eroded their internal cohesion, making coordinated action impossible and leaving themselves vulnerable to collapse or conquest. Over time, societies that minimized gratuitous suffering proved more stable, more resilient, and more capable of flourishing, which naturally pushed cultures, even very different ones, toward similar moral conclusions.

The point is not that every moral dilemma is simple, or that all harm is avoidable. The point is that harm is a morally relevant feature of the world, and any system pretending otherwise collapses into incoherence. A morality incapable of noticing suffering is like a navigation system that cannot state directions: it ceases to perform the function it was designed for.

Therefore, ethical reasoning must account for vulnerability not because we choose to make it important, but because the beings who use morality to guide their lives are vulnerable themselves . Morality that ignores this fact breaks at the root. In simpler words: moral systems must be responsive to harm because we are beings who can be harmed.

This requirement flows directly from the nature of sentience, and it sets the stage for the next step: understanding why a morality that disregards harm becomes not only inadequate, but self-contradictory.

2.3. Premise 3 — A Moral System That Ignores Harm Is Incoherent

If a moral framework claims to guide action but treats harm as irrelevant, it undermines itself from within. It tries to offer rules for living while ignoring the very conditions that make rules necessary.

Let’s consider what morality is supposed to do: It helps beings who can be harmed navigate a world where their choices matter. It identifies actions that protect well-being, actions that endanger it, and actions that allow a community to flourish instead of collapse. A moral code that ignores harm cannot fulfill this function. It becomes a set of empty gestures — a structure without foundation.

To see why, imagine a morality in which harm simply does not count. Murder and kindness would stand on equal moral footing. Torture and assistance would be morally indistinguishable. A parent who neglects a child would be treated no differently than one who protects it. The suffering of others would never impose a reason for action, and the prevention of suffering would never justify one.

Such a framework dissolves into contradiction the moment it is applied. The beings expected to follow it are themselves vulnerable; they depend on others to respect their lives, bodies, and dignity. They require a moral system precisely because harm exists, and will damage unless prevented.. A morality that pretends harm is morally meaningless and demands that sentient creatures navigate the world as if they were stones, as if injury, fear, deprivation, or death had no relevance to their lives.

This is incoherent.

It asks beings who can be harmed to reason as if they could not be harmed. It requires moral agents to ignore the very conditions that make moral agency possible.

Even moral systems that claim to be grounded in divine will, honor, virtue, or duty ultimately rely on harm in their structure. They condemn cruelty, betrayal, violence, and dishonesty not because of metaphysical preference, but because these actions damage individuals and communities. Remove the harm, and the moral weight evaporates. A “betrayal” that breaks no trust and causes no suffering ceases to be morally meaningful. A “lie” that misleads no one and endangers no one is trivial in the worst of cases.

Thus, the coherence of moral judgment depends on the reality of harm. A morality that ignores harm is not only unpersuasive; it is unusable. It contradicts the biology, psychology, and lived experience of the creatures it seeks to guide.

Morality cannot coherently function without taking harm into account, because ignoring harm empties moral concepts of their content.

This brings us to the next step: if morality cannot function without harm, then the principles that prevent unnecessary harm must hold a special place. They form the structural backbone of any coherent ethical system.

2.4. Premise 4 — The Emergence of the Pillars Principle

Once we recognize that harm is the central, unavoidable feature of moral life, something important becomes clear: Certain moral principles must appear in any ethical system that aims to guide sentient beings.

These are not cultural conventions or personal preferences. They arise directly from the structure of vulnerability itself. They are what we might call a Pillars Principle, a foundational constraint principle that prevents unnecessary harm and makes moral life possible.

Every moral tradition, no matter how distant in time or place, ends up converging on these principles in one form or another. They may express them through different stories, symbols, or authorities, but their substance remains the same. Why? Because they address universal threats to the well-being of sentient creatures.

Harm is finally defined deductively (not arbitrarily) as the potential threat factualized, any significant diminishment of a sentient being’s capacity to flourish — physically, mentally, socially, or structurally — including the destruction of safety conditions necessary for autonomy.

These Pillars Principle include ideas such as:

These are not arbitrary rules. They are practical responses to the risks that accompany being a creature who can be harmed. Remove the vulnerability, and the principles vanish; introduce vulnerability, and the principles reappear.

Even moral systems that seem unrelated (Confucian ethics, Stoic philosophy, Buddhist compassion, modern human rights, Indigenous codes of kinship) end up reasserting these core constraints. They may disagree on rituals, cosmology, metaphysics, or social norms, but they align on the prohibition of cruelty, the value of life, the importance of honesty, and the duty to prevent needless harm.

This convergence is not mystical. It is structural. Sentient beings require protection, trust, and cooperation in order to survive and flourish. Ethical systems that fail to provide these basic safeguards collapse or become indistinguishable from systems of domination and misery.

Thus, this Pillars Principle arises not from subjective taste, but from the very conditions of moral agency:

No moral system —human or divine— can demand obligations that destroy the very capacities that make obligation possible. This is the transcendental limit.

A being cannot have an “infinite duty,” or a duty to be perfectly self-sacrificial, because:

Thus, the Pillars Principle avoid:

Morality must protect vulnerability, not exploit it. These principles anchor morality in something deeper than culture: in the nature of sentient existence itself.

This sets the stage for the final premise: If this Pillars Principle arises in every coherent moral system, and if they are grounded in universal vulnerability, then the prevention of unnecessary harm is not merely one moral value among many, it is the objective foundation on which all morality stands on.

2.5. Prevention of Harm Is the Only Possible Candidate for an Objective Moral Foundation

Diminishment —and therefore harm— begins the moment biological, psychological, or environmental conditions convert vulnerability into actual functional impairment in any sentient being.

This means:

This respects the Harm Threshold Imperative while keeping the distinctions morally clear and operationally useful.

If we follow the argument carefully, step by step, the conclusion isn’t something we assert, it’s something we are forced into.

2.5.1. Morality requires a mind to which moral terms can apply.

Without a subject of experience, there is no “ought,” no “right,” no “wrong.”

2.5.2. The only feature of mind that makes moral concepts meaningful is the capacity to be harmed or benefited.

Nothing else (not culture, not divine decree, not social preference) is universally shared across all moral agents.

2.5.3. Harm, unlike moral norms, does not depend on belief or culture.

It is a real, biological, psychological, and phenomenological event. Pain receptors go off whether you believe in Kant, Confucius, or nothing at all.

2.5.4. Therefore, a moral framework rooted in the prevention of harm has an objectivity that other moral claims lack. It does not need to be “mandated” by a culture, religion, or ideology. It emerges from the simple fact that suffering exists and matters to the beings who experience it.

This does not magically settle every ethical question. It does not tell us how to rank all harms, resolve all dilemmas, or construct a complete moral code. But it does something far more fundamental:

It shows that if morality has any claim to objectivity at all, it must be grounded in the prevention of harm. Because there is no other universal, mind-independent, experience-dependent feature that can play that role.

Nothing else works. Nothing else even qualifies

A harm-based moral system includes a rational order of operations:

This structure prevents moral paralysis and ensures actionable judgments.

Part III: Defense and Application

3.1 Metaethical Foundations

Most people enter ethics hoping for guidance and leave with more confusion. It feels like walking into a library with a thousand different maps, each insisting it alone points to the true north.

Kantians talk about rational agency. Religious traditions talk about God’s will. Honor cultures talk about loyalty and shame. Contractarians talk about hypothetical agreements. And error theorists say morality never meant anything at all.

How could anyone expect to find objectivity in this philosophical mess?

This section is the clearing of the fog. Not by dismissing other theories, but by showing what they all secretly rely on: a universal precondition that makes moral reasoning possible in the first place.

This is not a moral opinion. It is an ontological fact.

3.2. What Makes a Moral Claim Moral?

We begin with the most basic question: what makes a moral claim moral? Unless we clarify this limit, any proposed foundation (harm or otherwise) floats without anchor.

For a claim to be moral, it must be able to speak to more than one person. It must have practical authority over agents regardless of tribe, religion, metaphysics, or personal history. This is called a public reason requirement: A moral claim must be justifiable to any agent who can reflect, act, and be affected.

If a claim applies only to people who share a scripture, or only to people who share a cultural code, it may be a norm, but it is not a moral foundation. A foundation must reach everyone.

This single requirement will become the lever that moves the entire world.

3.3. The Transcendental Question

Having clarified what moral claims must do, we now ask the deeper question: what must be true of the world for moral reasoning itself to make sense? This is where the foundation begins to emerge.

Instead of asking, “Which morality is true?”, we ask: What must be true for any moral reasoning to make sense at all?

Not “true for Kantians” Not “true for believers” Not “true for this or that culture” but true for the activity of moral reasoning itself.

And just like the rules of grammar underlie all languages, certain conditions must underlie all moral systems, whether people notice them or not.

Let 's find them.

3.4. The First Universal Condition: Sentience

With the framework of justification established, we now identify the first universal boundary of moral concern: the beings who can enter into moral space at all.

Morality is a practice among beings who:

A stone does not care about commands. An equation is not offended by injustice. Only sentient beings can enter moral space, because only they:

This is the simplest fact, yet it is the bedrock. Every moral claim is addressed to a mind that can be affected.

3.5. The Second Universal Condition: Vulnerability

The entire structure turns here. Sentience alone is not enough; moral relevance arises only when beings can be affected—when they can be helped or harmed.

This is the decisive insight.

Sentient beings are vulnerable—they can be damaged, diminished, destabilized. This vulnerability is the condition that gives moral claims weight.

Why? Because without vulnerability, nothing could matter to an agent.

If you were an invulnerable being:

In such a state, no “ought” would make sense. There would be no stakes.

Thus: Vulnerability is the structural precondition for moral relevance. Without it, morality would collapse into abstraction.

3.6. The Harm Threshold Imperative

Now that vulnerability is established as the core condition, we can define the boundary where moral relevance begins: the precise point at which harm occurs. We can define the category that morality must track:

Harm begins when a sentient being’s functional capacity to flourish is diminished—physically, psychologically, or in the safety required for autonomous life.

This gives us:

In everyday life:

This imperative is not a moral rule; it is an ontological boundary. A description of reality, like gravity or metabolism.

Now, we wonder: How could we ever possibly measure harm? Isn’t that too impossible to achieve? We would need to acknowledge every single risk that reality represents, right?

Right?

No.

The harm metric already exists, and it’s used today across human interaction. Medicine can objectively measure diminishment and decrease of functions and capacity (agency) for every sentient thing. We just need to quote it. Engineering already has established what represents a structural or environmental risk for sentiency. We use the gravity, permanency and depth of harm as the principle to declare restoration in cases when the vulnerability is violated.

But these measurements are not merely technical, they are moral inscriptions. Each time medicine diagnoses a pathology, law awards damages, or engineering defines a safety threshold, they are tacitly affirming that vulnerability matters, that flourishing has an objective structure, and that its diminishment creates a claim against the world. We are not just measuring harm; we are measuring the very thing that makes moral appeal possible.

We are already using harm as the principle, we just haven’t acknowledged it completely yet.

3.7. Why Harm Is Morally Primary (Demonstrated, Not Assumed)

This is where the argument answers its hardest challenge: is harm truly unavoidable as the foundation of morality, or merely asserted? The answer rests in the logic of justification itself. Here we finally address and overcome the final the critique: the transcendental step must be demonstrated, not asserted.

The key is this:

P1. A moral claim must appeal to something that has practical authority over a sentient agent (public reason requirement).

P2. Practical authority requires that the claim relate to the agent’s conditions of flourishing or vulnerability.

Otherwise it cannot guide action. A norm that has no bearing on a being’s condition has no grip.

Thus:

P3. All moral systems must —implicitly or explicitly— rely on the vulnerability of agents to justify their rules.

And therefore:

C. Harm becomes the minimal, unavoidable, universal grounding of moral relevance.

This is not an assertion. It is a transcendental demonstration.

Let’s test it.

3.8. Defending the Harm Principle Against Objections

Even if the prevention of harm emerges as the only viable candidate for an objective moral foundation, the view faces familiar challenges. Critics argue that harm is too subjective, too variable, or too limited to ground morality. Others claim that moral life rests on loyalty, purity, duty, divine command, rationality, or cultural cohesion — not merely on harm.

But when examined closely, these objections dissolve. The reason is simple: harm is the only feature of the moral landscape that is both universally relevant and objectively grounded in the biological reality of sentient life.

Let us take the objections one by one.

3.8.1. Objection 1: “Harm Is Subjective; People Disagree About What Counts as Harm.”

It is true that individuals and cultures disagree about which harms matter most, or how they should be weighed. But this variation does not undermine the objectivity of harm itself.

Confusion arises from conflating:

A burn, a broken bone, terror, deprivation, and psychological anguish are not cultural constructions. They are consequences grounded in what sentient nervous systems can undergo.

Disagreement does not erase universality.

People disagree about justice, temperature comfort, and risk tolerance, yet heat, risk, and fairness remain real phenomena. What matters for moral objectivity is not universal agreement but universal applicability. And harm applies to all creatures capable of suffering.

To make this explicit:

Harm remains objectively definable because it is anchored in the biological and existential vulnerability of sentient beings — not in cultural consensus or individual preference.

This is the foundation upon which the entirety of every moral principle structure rests.

3.8.2. Objection 2: “Some Moral Principles Seem Unrelated to Harm.”

Many point to norms such as:

These appear to be “harm-independent.” But this is an illusion caused by historical distance or symbolic obscurity. Each of these norms derives its moral force from its relationship — direct or indirect — to the prevention, mitigation, or distribution of harm.

Examples:

A rule completely unrelated to harm would have no consequences when violated. And a rule with no consequences has no moral force.

Thus:

If a principle truly had no connection to harm, its violation would produce no meaningful outcome, and its moral authority would become rationally empty.

Morality without harm isn’t just weak. It is incoherent.

3.8.3. Objection 3: “What About Self-Chosen Harm?”

People willingly engage in risky or painful behaviors: extreme sports, piercings, heroic sacrifice, demanding professions. Does this undermine a harm-based morality?

Not at all. This objection assumes that “harm” and “immorality” are identical, but this framework never claims that.

The objective foundation is:

When a competent sentient agent chooses to accept a harm, and no one else is unjustly affected, the action falls outside moral condemnation. This distinction fits cleanly within the harm principle.

3.8.4. Objection 4: “What About Conflicts of Harm?”

Often, protecting one party harms another. Reducing overall suffering may increase suffering for a few. Real moral life is full of trade-offs. But this is not an argument against the harm principle, only an argument that the world is complicated.

The crucial point is this:

Even when harms conflict, the moral system still operates within a single evaluative currency. The Pillars Principle of harm prevention remains the unit of measure.

We are not juggling loyalty vs. purity vs. divine will vs. social custom vs. intuition. We are weighing harms, the same kind of quantity across different parties. This makes moral reasoning difficult, but not incoherent. Trade-offs become calculations within a shared framework, not clashes between fundamentally incompatible principles.

3.8.5. Objection 5: “Isn’t This Too Simple?”

Some worry a harm-based morality is reductive. But foundational principles in all domains are simple:

A foundation’s job is not to capture complexity — it is to make complexity intelligible. The harm principle does exactly that. It explains:

What appears simple is actually morphologically and structurally elegant. It is not a flattening of moral life, but the framework that makes moral life possible.

3.8.6. Positive Implications of a Harm-Based Moral Realism

If the prevention of harm is the objective foundation of morality, then several important consequences follow. These consequences do not merely tidy up philosophical debates; they illuminate why morality matters, why it applies universally, and why it carries the weight it does in human life.

Morality becomes clearer, not smaller. Its authority becomes firmer, not weaker. And its purpose becomes unmistakable.

3.8.7. A Unified Framework for Moral Reasoning

A harm-based foundation generates a moral landscape that is cohesive rather than fragmented. Instead of juggling countless moral theories (virtue ethics, deontology, divine command, care ethics, contractualism) each with different starting points, we gain a single architecture from which they can be understood.

Under this view:

When morality splinters into incompatible axioms, reasoning collapses into conflict. But if all branches of moral life trace back to the same Pillars Principles, then the entire structure becomes intelligible.

The singularity is not imposed, it is discovered.

3.8.8. Why Morality Applies Only to Sentient Beings

If harm is the foundation, then the scope of morality becomes unmistakably clear.

Moral concern extends to any being capable of:

This includes humans, animals, and potentially artificial forms of consciousness, but excludes objects, landscapes, abstract entities, or fictional characters.

A rock cannot be wronged.

A river has no subjective experience.

A robot without sentience is not a moral patient.

The moral circle is not defined by species or metaphysics, but by the capacity to be harmed and sentiency. This makes the moral boundary neither arbitrary nor culturally constructed, but rationally grounded.

3.8.9. A Clear Separation Between Moral and Non-Moral Norms

Many social norms (table etiquette, dress codes, rituals, community customs) have nothing to do with harm. A harm-based foundation lets us distinguish:

from

This distinction benefits ethics enormously. It allows us to say, without hesitation:

Once morality is grounded, it stops being a cultural grab-bag. Its boundaries are principled, not set.

3.8.10. A Critical Framework for Cultural and Religious Norms

If morality is objective, cultures and religions can be evaluated, not simply described.

Some cultural norms protect communities from harm; others perpetuate it. A harm-based foundation lets us say:

This moves us beyond cultural relativism. Morality does not bend to tradition. Tradition bends to morality. And morality bends to the objective vulnerability of sentient beings.

3.8.11. A Foundation for Human Rights

Human rights often appear mysterious or metaphysically heavy. But they need not be.

Rights function as institutional protections against predictable forms of harm:

Understood this way, rights become rational tools, not mystical aspirations. Their moral force is not arbitrary, it is grounded. They matter because harm matters.

3.8.12. Moral Progress Becomes Legible

History is filled with moral transitions:

What do these changes have in common?

They expand moral concern to beings previously ignored or mistreated. They reduce preventable suffering and increase the possibility of flourishing.

Moral progress becomes visible as the widening of the moral circle and the systematic reduction of harm.

This is not coincidence , it is the structural logic of moral development unfolding in history.

3.8.13. Hard Truths and Urgent Implications for Today’s World

If morality has an objective foundation in the prevention of harm, then several deep, uncomfortable truths follow. These truths are not ideological positions but logical consequences of the framework. They demand attention across political philosophy, education, medicine, corporate behavior, law, and AI ethics.

They are not pleasant. But they are necessary.

3.8.14. Political Philosophy: Policies Must Be Measured by Harm, Not Identity or Ideology

Modern politics treats morality as a disposable flag. But if the foundation of morality is objective, then political claims can be evaluated without tribal lenses.

This leads to unavoidable conclusions:

When harm becomes the standard, political debate becomes moral evaluation, not power struggle. And many widely defended policies become indefensible overnight.

3.8.15. Education: We Must Teach Moral Reasoning, Not Obedience

If morality is rooted in the capacity to be harmed, then education must shift:

This means:

A society that teaches obedience but not moral reasoning produces citizens who follow harmful orders without question. A society grounded in harm-based ethics cannot allow that.

3.8.16. Law: Legal Systems Must Stop Treating All Offenses as Equal

If harm is the foundation of morality, then:

not to tradition, symbolism, or outdated moral codes.

This implies:

Under a harm-based framework, the justice system becomes coherent and humane: Punishment is not retribution; it is harm prevention.

3.8.17. Medicine: Patient Suffering, Not Institutional Habit, Must Drive Decisions

If harm is the grounding of morality, then medicine must confront its contradictions:

This also means confronting uncomfortable realities:

The moral language of medicine becomes clearer: Health care is harm prevention. Neglect is harm infliction.

3.8.18. Corporate Ethics: Profit Cannot Justify Systematic Harm

In business, harm often becomes invisible because it is distributed, indirect, or normalized.

A harm-based moral realism cuts through the fog:

Under this framework: You cannot hide moral damage behind spreadsheets, legal disclaimers, or complexity.

Harm scales. So does moral responsibility.

3.8.19. AI Ethics: Sentience, Harm, and Power Must Define Our Obligations

AI brings radically new challenges, and the harm-based foundation provides rare clarity.

a. Non-sentient AI

If an AI system is not sentient, then:

This implies:

3.8.20. Future sentient AI

If artificial consciousness emerges, the moral circle must expand, not because AI is special, but because it becomes a being capable of experiencing harm to its agency (synthetic but real). This is not science fiction; it is an ethical horizon we must prepare for.

3.8.21. Power asymmetry

Finally, AI introduces the most dangerous form of harm:

A harm-based foundation becomes not only philosophically important, but practically urgent.

3.8.22. Environmental Stewardship: The Planet Itself Is Not a Moral Patient, but Life On It Is

This is a hard truth many avoid:

This means:

This clears away the metaphysical fog around nature ethics. The planet does not feel. But living beings do.

And their vulnerability binds us.

3.8.23. The Hardest Truth

When harm becomes the foundation of morality, we lose the comforting illusions that:

We are left with a simpler, heavier reality: Where there is avoidable suffering, there is moral failure. Where there is preventable harm, there is moral obligation.

The world becomes clearer, nd our responsibilities much harder to escape.

3.9. Contrasting Moral Frameworks: A Clearer View of What Failed

If the prevention of unjustified harm is the only principle that survives universal scrutiny, the contrast becomes stark when we place it beside the great moral codes humanity has followed. These systems often appear authoritative, ancient, or socially entrenched, but their foundations reveal something very simple: none of them offer a rational grounding that applies to all sentient beings in all conditions. Only the harm principle does.

Below, we pass through three major moral landscapes: biblical Christianity, liberal democracies, and authoritarian regimes, to see what becomes of them when examined under the lens of the Pillars Principle.

3.9.1. Biblical Christianity: Morality by Decree, Not by Experience

Believers Already Presuppose Harm (even when they deny It). Religious morality does not escape the harm framework—indeed, it relies on it. The ultimate punishment in many traditions is eternal harm (hell), and the ultimate reward is the removal of all harm (heaven). Even believers who claim that “God’s will defines morality” implicitly acknowledge that harm is morally decisive, because the entire motivational structure of divine command systems depends on avoiding the greatest possible harm.

Thus, even the moralities that deny harm as foundational secretly use harm as their foundation.

Biblical morality rests not on experience, suffering, or the shared conditions of sentient life, but on divine authority. Something is wrong because God commands it; something is permitted because God allows it. This means that harm is not the essence of wrongdoing — disobedience is.

This is why, in scripture:

Moral relevance does not arise from the ability to suffer but from possessing a soul, or being designated as sacred or damned. Animals matter only insofar as they relate to human conduct and will. Non-sentient objects can acquire moral significance if they enter the sphere of the divine.

In contrast, the Pillars Principle recognizes moral standing wherever sentience is present, and only there. Stones have no moral status; sacred stones only have the status a culture projects onto them. Under the harm principle, the moral weight of an action depends on whether a sentient being is affected, meaning biblical morality often assigns moral value where none exists and withholds it where it should be central.

The Pillars Principle is not merely a survival rule for the vulnerable; it is a Truth of Pure Logic derived from the concept of Coherent Agency and Descartes’ deduction.. If a non-vulnerable agent (like God) chose to act arbitrarily by inflicting harm where no necessity demanded it, that act would not be a violation of the victim's body, but a violation of the Structure of Coherence itself. It would be the equivalent of choosing 2+2=5. The law binds the non-vulnerable because it is the logical prerequisite for rational, non-arbitrary action, even and especially in the presence of infinite capability.

Christian ethics has drifted toward compassion and harm-prevention not because of divine decree, but because those elements are the only parts of it that survive rational examination.

3.9.2. Liberal Democracies: A Moral System That Knows the Answer but Hasn’t Said It Yet

Modern liberal morality (the ethics of rights, autonomy, freedom, and protection) implicitly depends on harm as its foundation, even when it doesn’t name it. You see it everywhere:

Even debates about fairness, equality, and autonomy ultimately converge on preventing unjustified harm: the harm of discrimination, deprivation, coercion, or suffering imposed without cause.

Liberal societies therefore operate on a proto-version of the Pillars Principle. They intuitively respond to harm, measure justice through harm, and regulate conduct in order to mitigate it. But they do not always articulate the foundation explicitly. They still maintain historical customs, outdated taboos, and inherited notions of “rights” whose justification is no longer clear.

What this framework does is give liberal ethics the philosophical grounding it lacks. It explains why harm matters, why rights exist, and why autonomy is morally relevant: because these concepts track the conditions that protect sentient beings from unjustified suffering.

Liberal morality is closest to objectivity — it simply needs the foundation this principle provides.

3.9.3. Authoritarian Regimes: The Complete Rejection of Moral Reality

If biblical morality grounds ethics in divine authority, authoritarian moralities ground it in human authority: The will of a ruler, the survival of a state, or the goals of an ideology. In such systems, actions are not wrong because they cause harm; they are wrong because they challenge power.

A harmless act can be punished brutally if it contradicts the ruler’s interests. A harmful act can be celebrated as patriotic if it strengthens the state.

This is why:

Moral standing is selective. Citizens matter only if they are useful; dissidents, minorities, and the vulnerable are treated as morally negligible. Animals have no status at all. Even human suffering is irrelevant unless it disrupts the machinery of control.

Seen through the Pillars Principle, authoritarian ethics collapses immediately:

These systems do not merely fail to be objective; they fail to be moral. They replace moral reality with power dynamics, mistaking force for justification.

3.9.4. What the Contrast Reveals

When you set these moral systems side by side, the difference becomes unmistakable:

Only one framework derives morality from something that is universal, empirically real, and shared by all beings capable of suffering. Only one framework explains why any moral rule matters in the first place. Only one framework applies across cultures, religions, eras, political systems, and species.

The Pillars Principle, grounded in harm and sentience, is not simply another moral code. It is the only foundation that remains coherent once everything else has been tested.

3.10. The Pillars Principle (Corollaries)

These are not arbitrary rules, nor culturally inherited norms, but analytical consequences of the core argument.

3.10.1. The Negative Constraint

Do not inflict unnecessary harm.

If moral relevance arises only where harm is possible, and if harm is the very thing that grounds moral concern, then the first universal rule is strictly prohibitive:

Avoid causing harm unless doing so is absolutely necessary to prevent greater harm.

This captures the logic of self-defense, medical intervention, and justified coercion — all cases where harm is regrettably allowed only to reduce larger harm.

Any moral system that denies this collapses into contradiction, because it would harm the very beings whose vulnerability is the foundation of moral reason.

3.10.2. The Positive Duty

Act to reduce preventable harm and suffering where possible. Once we accept that vulnerability matters because harm matters, it follows that:

This does not demand heroic sacrifice of everything, only that one’s moral obligations extend beyond mere non-aggression. The principle is proportional, grounded in practical capacity and context.

It reflects what philosophers like Peter Singer, Martha Nussbaum, Thomas Scanlon, and Derek Parfit have argued: that preventing needless suffering is not charity, it is a rational conclusion of the same logic that forbids causing suffering.

Together, the two principles form a complete moral architecture, dual-engine.

The Negative Constraint tells us what not to do. The Positive Duty tells us what we should do. Between them lies the entire landscape of practical ethics, political philosophy, and global moral reasoning.

And crucially: They are not culturally relative or spiritually revealed, they are analytically required by the foundational argument.

The Pillars Principle establishes the objective moral floor (the 'necessary minimum'). It defines which actions are universally and rationally wrong by violating the Wrongness Formula and the Harm Prevention Principle. It is an ethic of minimal rational obligation that prohibits structural wickedness.

It does not constitute a 'moral ceiling' that prescribes all correct action, nor does it prohibit supererogatory actions (beyond duty), such as altruism or benevolence; it simply does not make them obligatory under the rigor of rational coherence. A society based on The Pillar Principle (Negative Constraint/Positive Duty) is just; a society based on altruism is virtuous, but justice is the only objectively binding basis.

The Positive Obligation to prevent avoidable harm (the positive duty) is inherently conditioned by the Rational Agency of the moral subject. Rationally, a system cannot demand the fulfillment of a duty that exceeds the agent's capacity. Therefore, the positive duty is modulated by physical distance, available knowledge, accessible resources, age, and, in general terms, the reasonable agency of the individual.

This prevents the objection that the system demands unlimited and irrational altruism (e.g., demanding that an individual sacrifice or exhaust their vital resources for a distant stranger). The obligation stops where the reasonable capacity of the agent ends.

Part IV: Formal Theory

4.1. The Pillars Principle in Full Prose

Once the foundation of morality is grounded in the universal condition of vulnerability ( the simple, undeniable fact that sentient beings can be harmed the entire moral structure becomes illuminated. From that foundation, two principles rise with the force of inevitability. They are not commandments, nor cultural inheritances, nor intuitions polished by tradition. They are the logical pillars that any coherent ethical system must stand upon.

4.1.1. The Negative Constraint: Do Not Inflict Unnecessary Harm

The first principle is prohibitive, sharp, and uncompromising.

If harm is the very thing that makes morality possible — the reason we distinguish right from wrong at all — then the primary obligation is to not increase it without necessity.

This principle is not sentimental. It is structural.

To deliberately harm a sentient being is to undermine the very condition that gives morality its meaning. It is to deny the relevance of the vulnerable other while simultaneously relying on vulnerability to justify this own protection. It is a contradiction that collapses all moral reasoning.

Thus, the Negative Constraint emerges:

Avoid causing harm unless doing so is the only way to prevent greater harm.

This principle justifies self-defense. It justifies coercion against aggressors. It justifies medical interventions that hurt in order to heal. It justifies the hard decisions of triage, resource allocation, and legal enforcement.

But it also condemns: Gratuitous cruelty, exploitation, discrimination, domination, needless war, and every exercise of power that inflicts injury without reducing a larger suffering.

It is the moral equivalent of gravity; always present, always binding.

4.1.2. The Positive Duty: Reduce Preventable Suffering

The second principle flows from the first, but expands it.

If we accept that harm is morally relevant because vulnerability is morally relevant, then wherever we can meaningfully reduce suffering, we acquire a duty to do so, provided the cost does not impose a greater harm elsewhere.

This is not moral heroism. It is moral coherence.

A world where no one may hurt others but no one is required to help others is incoherent: it treats harm as morally decisive only when caused by action, not when caused by neglect. But suffering does not respect that distinction.

Thus the Positive Duty arises:

When you can prevent substantial harm at reasonable cost, you ought to.

This principle underlies:

The Positive Duty does not demand sainthood. But it does demand seriousness.

It requires institutions, laws, and citizens to treat preventable suffering not as an unfortunate fact of life, but as a solvable moral problem.

Together, they form the Architecture of the only Moral World we know.

The Negative Constraint protects beings from unjustifiable harm. The Positive Duty elevates beings by reducing avoidable harm. Between these two poles, the entire landscape of moral and political life becomes legible.

Every question of justice, equality, rights, governance, medicine, war, economics, education, and technology can be translated into this shared grammar: Does it inflict unnecessary harm? Does it reduce preventable suffering?

These two questions do not solve every problem — but they render every problem morally intelligible. They provide humanity with something it has never had: A universal, rational moral compass grounded not in culture, revelation, or tradition, but in the shared condition of all sentient life.

The Foundation Moral Philosophy has been searching for. We have not claimed that harm explains everything. We have shown something deeper:

Harm is what all moral systems must presuppose for their principles to matter, justify, bind, or condemn.

It is not a preference. It is a structural necessity.

And it gives us the bedrock:

Thus:

Preventing unnecessary harm is the only possible objective foundation of morality.

Deductively brutal.

So far, we have determined that if morality is to exist, it must be based on harm: the reduction of a sentient being's ability to thrive. However, acknowledging harm as the basis is different from understanding how to assess it.

Reality presents us with challenging situations: a monk who voluntarily fasts but asserts spiritual growth; a billionaire sacrificing riches so that many children can recover their vision; a community making current sacrifices to avert future environmental disaster. These conflicts show that although harm serves as the common baseline, we still do not have a clear guide for comparing harms with one another.

The aim is to establish an objective, non-arbitrary, rationally binding foundation for comprehending what flourishing entails, how harm reduces it, and how to assess competing harms without depending on intuition or cultural prejudice. In other terms, we transition from determining the basis of morality to developing a method for measuring morality.

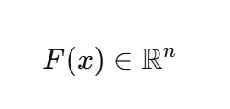

4.2. Why Flourishing Must Be Multi-Dimensional

If harm is the diminishment of a being’s capacity to flourish, then we must understand what “flourishing” actually means. And the first thing to recognize is that flourishing cannot be reduced to a single variable—like pleasure, income, autonomy, or health. Sentient life is simply too complex for one dial to capture its well-being. A human can have wealth but no relationships, health but no purpose, freedom but no stability. A monk fasting voluntarily, a billionaire losing a fraction of his fortune, and a child gaining access to clean water each illustrate different dimensions of flourishing that rise and fall independently. This is why any meaningful account must be multi-dimensional, capturing the universal capacities that allow a life to go well: the ability to avoid pain, to move freely, to form bonds, to think clearly, to pursue goals, to live without coercion, and to maintain a stable environment. These dimensions are not arbitrary—they are the shared conditions under which sentient beings survive, act, and experience.

4.2.1. Constructing an Objective Harm Metric

We now assemble these elements into a functional harm metric: a way to determine, case by case, where real harm occurs and how conflicting harms must be weighed.

With the foundation secured (that morality must be about harm) we face the next challenge: how to measure harm in a non-arbitrary, rational way. This part builds that metric. Real moral problems are not about obvious harms but about conflicting harms. To handle these without arbitrariness, we need a principled way to evaluate them.

4.2.2. Defining the Baseline: The Universal Core of Flourishing

Harm is the diminishment of flourishing; then any attempt to measure harm objectively must begin with a clear account of what flourishing actually consists of. The challenge is to identify elements of flourishing that are not tied to culture, religion, personality, or taste, but rather to the shared structure of sentient life. We are not looking for “what people happen to value,” but for what any being with a mind must have in order to avoid suffering, to pursue goals, and to remain capable of agency.

In this sense, flourishing is not a feeling and not a preference, it is a set of capacities without which sentient existence goes poorly. A being who cannot avoid pain, cannot understand the world, cannot form intentions, cannot sustain bodily integrity, or cannot maintain psychological coherence is not merely “less happy”—they are harmed in a deep and recognizable sense.

To make this concrete, consider three examples:

These cases show that flourishing is best understood as a set of core functional abilities that allow a sentient being to live, choose, understand, and participate in a meaningful world. When these abilities are damaged or constrained without necessity, harm occurs objectively.

From here, the harm metric begins to take shape: Harm is the deprivation, erosion, destruction or obstruction of a universal capacity required for sentient flourishing. The key insight is that flourishing is not a single quantity. It is a structure of universal capacities shared by all sentient life

4.2.3. The Structure of the Harm Metric

Once we recognize that harm is not a single quantity but the diminishment of universal capacities, a structured, non-arbitrary metric begins to emerge. Each capacity can be evaluated independently, but all share the same logical function: they are conditions that any sentient being needs in order to live, act, plan, and maintain well-being.

This allows moral reasoning to become comparative and principled rather than intuitive or culturally loaded. A punch to the face, censorship, starvation, social exclusion, environmental poisoning, economic coercion, manipulation, and torture all become commensurable, not because they are the “same kind” of harm, but because they each attack a capacity required for flourishing.

Thus the question “Which action causes more harm?” becomes:

Which action destroys or restricts more essential capacities, more deeply, more permanently, and with fewer viable alternatives for restoration?

This avoids the naïve utilitarian mistake of reducing everything to pain units, and avoids the Kantian mistake of ignoring empirical consequences altogether. Instead, it yields a multi-dimensional, evidence-based framework where different harms can be compared because they have a shared reference class: the universal scaffolding of flourishing.

Necessary Purposes that precede flourishing:

Safety: We begin with the most basic layer: the conditions that keep a being alive and unviolated.

Autonomy: Next, the capacity to direct one’s own actions (the core of agency and necessary pre-condition for a moral judgement); these only matter if the agent is “allowed to choose” between the moral (coherent) and immoral (incoherent) option.

Capability: Then the abilities that make life more than mere survival (secondary agency potentials)

Social Embeddedness: Finally, the relational matrix that sustains cooperation and meaning and the possibility. The environment is included here.

4.2.4. The Harm Metric Must Be Intersubjective, Not Subjective

To avoid relativism, the harm metric cannot depend on individual preferences (“I flourish when I suffer”) or cultural traditions (“Our society values silence over health”). Instead, the metric must be intersubjective; that is, grounded in conditions that any rational agent must acknowledge regardless of personal taste or cultural background.

A single monk may claim that fasting and isolation increase his flourishing; a billionaire may insist that losing half his wealth harms him more than a million children losing their sight. But these statements cannot serve as the basis of a universal moral system, because they rely on idiosyncratic value judgments. Intersubjectivity requires something stronger: reasons that any agent, placed behind a veil of their own vulnerability, would be compelled to recognize.

This does not erase individuality. It simply means that, when constructing a moral framework intended for everyone, we prioritize the capacities whose loss any rational agent would fear, and whose preservation any rational agent would demand. Hunger, coercion, violence, deprivation of movement, untreated illness, psychological terror, these are not matters of preference. They are structural disruptions of the basic conditions that make any life, in any culture, capable of going well.

In this approach, the monk's choice to fast voluntarily is not seen as harmful (as it does not significantly diminish a universal ability when selected willingly). Yet, forcing starvation upon someone against their will is always considered harmful. The billionaire's discomfort doesn't compare to a child's blindness because the reduction in wealth doesn't diminish a fundamental ability like the loss of vision does.

Therefore, the harm metric achieves objectivity without rigidity and universality without enforcing a singular way of life. It characterizes harm not based on feelings, but on what any sentient being needs to sustain the fundamental structure of a thriving life.

4.2.5. Objection 3: The Denial of Coherence (The Attempt at Rational Suicide)

The most sophisticated attempt to refute the Pillars Principle does not come from the relativist (who accepts morality as a preference), but from the radical skeptic or nihilist who seeks to demonstrate that morality is an illusion and that Reason is merely a tool serving the annihilation of agency. This contradictor must attempt to separate morality from coherence, arguing that the destruction of agency is, in fact, the act of maximum rationality ("rational suicide").

The Demonstration of Inescapable Incoherence:

This thesis is structurally impossible to prove without self-destructing, which confirms, by reductio ad absurdum, the necessary truth of the Pillars Principle Axiom.

Please, bear with me:

The Performative Contradiction: For the nihilist to argue that the preservation of agency is an error and that its annihilation is the ultimate truth, they must utilize Reason (the capacity for logical deliberation) and Language (the communicative capacity of agency). The act of formulating the thesis affirms the indispensability of Reason and functional Agency as the only tools capable of attaining truth. If Reason is the only tool for accessing truth, then protecting that tool is the highest logical imperative. By using Reason to argue that Reason must cease, the contradictor commits an immediate logical self-contradiction.

The Functional Denial: Morality defines Evil as the detriment of agency and Good as its protection. The contradictor must prove that Maximum Harm (annihilation) is the Maximum Good, which constitutes a denial of the functional definitions that Reason uses to operate. This is not just an ethical contradiction; it is an incoherence of functional categories as fundamental as arguing that 1+1=3 and that this result is the most coherent one.

The Structural Conclusion: Morality is not an option for the rational agent; it is the condition of coherence that allows Reason to exist and operate. The Pillars Principle thus becomes a Transcendental Logical Law. The contradictor is obligated to prove a metaphysical state where self-contradiction is the highest truth. Since any attempt to demonstrate this thesis uses Reason to confirm its value, the refutation self-destructs in the process of its formulation.

4.2.6. Why This Framework Avoids Arbitrary Weighting

Every traditional attempt to quantify harm collapses for the same reason: They begin with intuitions and then search for principles, instead of beginning with the structural requirements of sentient life and deriving principles from them.

The multi-capacity framework avoids this trap because the weights emerge from necessity, not preference.

Some capacities are Foundational: Without them, no other dimension of flourishing is possible. Others are Supportive: They enrich life but do not enable its core functioning. And some are Contextual: their importance shifts with the environment but remains tethered to the same underlying structure.

This is not arbitrary because:

In other words:

The relative weight of each capacity is determined by its structural role in enabling sentient agency and well-being.

A framework built this way does not have to guess or negotiate which goods matter more; their significance is written into the architecture of sentience itself.

This is what ultimately provides a solid foundation for a harm-based morality: Not due to the simplicity of flourishing, but because the requirements for flourishing are necessary. They serve as the framework for any reality in which moral assessment is conceivable.

4.2.7. The Harm Metric Is Intersubjectively Binding, Even Across Disagreement

A moral foundation must do more than describe harm; it must generate reasons that any rational agent can recognize, even if they do not like or prefer those reasons. The power of the Harm Metric is precisely that it anchors moral judgment in publicly observable impairments of universal capacities. You may disagree about ideals, values, or metaphysics, but you cannot rationally deny that a broken leg restricts mobility, that starvation impairs agency, that trauma destabilizes psychological integrity, or that coercion erodes autonomy. These are facts about the structure of sentient life, not interpretations layered on top of it.

Because the metric is tied to the conditions that make any life go well, its authority does not depend on cultural norms or subjective tastes. A monk, a billionaire, a libertarian economist, a Buddhist sage, a Christian pastor, and a secular materialist will disagree about many things, but they cannot deny that certain forms of deprivation objectively constrain the ability to function and flourish. This is the domain where disagreement shrinks to zero: the domain where bodily violation, coercion, degradation, and life-limiting damage manifest as measurable impairments.

Thus, even when preferences differ and worldviews clash, the Harm Metric remains publicly intelligible. It does not need unanimity, only recognition of facts that no rational agent can coherently deny without undermining their own claims to agency. That is what makes the framework universal: it binds not through authority, but through the logic of shared vulnerability itself.

4.3.The Ultimate Moral Imperative That Binds Even a God

The preceding argument has demonstrated that moral objectivity is not a flight of metaphysical fancy but an existential imperative rooted in the factual reality of sentience and vulnerability. The Principle of the Prevention of Unnecessary Harm emerges not as a proposition we choose to accept, but as a truth we must acknowledge if our ethical system is to remain internally coherent and structurally sound.

Even omnipotent beings must choose what counts as good. If they choose arbitrarily, their commands lose moral force. Moral authority requires public reasons. Public reasons require harm-based justification.

Thus:

If a deity wants His commands to be morally authoritative, He must operate within the harm framework. Otherwise He issues commands, not morality.

Having successfully withstood the most rigorous metaethical challenges, the framework now stands confirmed:

4.3.1. The Necessity of the Objective Constraint

The final objections hinged upon the framework's applicability in the face of human limitation and complexity, questioning whether the principle could survive the real-world demands of omission, conflict, and future existential change.

4.3.2. The Power of Contingent Objectivity

Perhaps the most potent defense is the acknowledgment that the morality derived from harm is contingent upon the existence of sentient beings. The claim is not that this is the ultimate truth of a dead cosmos, but that it is the ultimate truth for our moral universe.

If, hypothetically, humanity were to develop technology that eliminated all vulnerability, pain, and the potential for lost agency —if the condition of sentience no longer included the capacity for harm— then the moral framework would dissolve. This is not a weakness; it is the ultimate proof of its objective reality. Morality is a solution to the problem of suffering. If the problem ceases to exist, the solution is no longer necessary.

4.3.4. God is Bound

This final clarity leads to the radical conclusion embedded in the title: The Principle of the Prevention of Unnecessary Harm is a structural necessity of existence. It binds not because it is decreed by a powerful being, but because it is the condition of coherence for any action in a world with sentient beings.

The framework we have established is thus impregnable: it is a universal truth that operates independently of belief, tradition, or custom, and serves as the unshakable foundation upon which all rational, moral life must be built.

Disclaimer:

This metric is not a final blueprint but the first coherent, non-circular model for quantifying moral harm. Like all scientific and normative models, it will require refinement, but its architecture —grounded in universal capacities— provides the only viable basis for objective adjudication of conflicting harms.

The theory is not claiming to be an eternal, timeless truth that governs empty space. It is asserting that the Moral Domain is Co-Extensive with Vulnerability. Morality is the Structural Solution to the Structural Problem of vulnerability. Therefore, the absence of the solution (morality) in a universe where the problem (vulnerability) is definitionally absent (Omega Universe) is not a flaw in the theory, but a principled delimitation of its scope. The only way for the Law of Structural Harm to be false is for sentient existence to be impossible.

Part V: Formalization of the Argument

5.1. Axiomatization

We divide the system into:

5.1.1. Primitives

P1: Sentient beings

Plain meaning: The group of beings who can feel, suffer, or flourish.

P2. Flourishing function